Thousands of Black and Hispanic Americans could go uncounted in the nation’s census this year because of the coronavirus pandemic and other disruptions that discouraged households in poor and heavily minority neighborhoods from filling out their forms.

In 63% of census tracts, fewer people provided initial responses this year than in 2010, a USA TODAY analysis found. Response rates fell particularly in tracts with high concentrations of Black or Latino residents, large percentages of families qualifying for government benefits, or low levels of access to broadband internet.

The analysis does not include information the Census Bureau has gathered during a massive door-knocking operation currently underway. Officials say 84% of all homes have now been “enumerated,” up from 65% filing forms on their own.

But the bureau hasn’t released detailed data that would show whether this late-summer outreach closed the gap in response rates among neighborhoods. The bureau also offered no way to compare its new enumeration rate with numbers a decade ago.

“My biggest fear, and my estimate, is that we’re headed towards an extremely flawed census,”said Paul Ong, a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles who has conducted research that generally mirrored USA TODAY’s findings.

The findings underscore the stakes for the Census Bureau’s in-person follow-ups, which end September 30, a much tighter timeframe than a decade ago. The bureau may stop work in some cities even sooner, and critics say a quick turnaround will leave numbers skewed.

Census population counts are used to distribute congressional seats and federal funding. An undercount can cost communities hundreds of billions of dollars used to pay for school lunches, highway construction, state public water systems, substance abuse treatment, Medicare, Head Start, and dozens of other programs.

Responses in Puerto Rico declined the most, from 54% last time to 32% this year.

Among the 50 states and the District of Columbia, the steepest drop in people initially answering the Census was in the South, where internet access is more sparse and poverty levels are higher compared to other regions. South Carolina, Texas and North Carolina led the region in declines, with response rates each falling more than 6% since 2010.

More: 2020 census 'emergency' threatens to leave out communities of color

One study found Texas would have lost almost $300 million in a single year if it had an additional 1% undercount on the last Census. Similar undercounts would have cost North Carolina almost $100 million and South Carolina almost $40 million.

Census Bureau officials point to the army of workers trying to reach people who haven’t responded.

"I can say with real confidence, we are in an incredibly good place right now with completing a full and accurate count," said Tim Olson, the bureau’s associate director for census field operations.

Olson said workers are processing almost 2.5 cases per hour, exceeding a goal of 1.55.

"We've got the technology, we have the people, we're moving ahead and it's feeling pretty good," he said.

But some people who track the census are skeptical there’s enough time left.

Ong, the UCLA researcher, said historically lower responses from low-income families and people of color early in the 2020 count will likely hinder efforts to catch up.

“Throughout the process, the Bureau has been telling people they will be able to close the gap,” Ong said in an email.

“I hope they are right,” he said, “but I would like to see the evidence that confirms this.”

People of color and poor families are undercounted every census. But COVID-19 delayed delivery of Census questionnaires for hard-to-reach populations during the spring quarantine and delayed operations since then to reach households that failed to respond.

Advocacy groups say another major factor in the drop in response rates is President Trump. He issued a recent presidential memorandum excluding undocumented immigrants from apportionment counts for 435 House seats, and a 2019 executive order -- ultimately overturned in court -- adding a citizenship question to the census.

More: Trump tells census to not count undocumented people for House apportionment

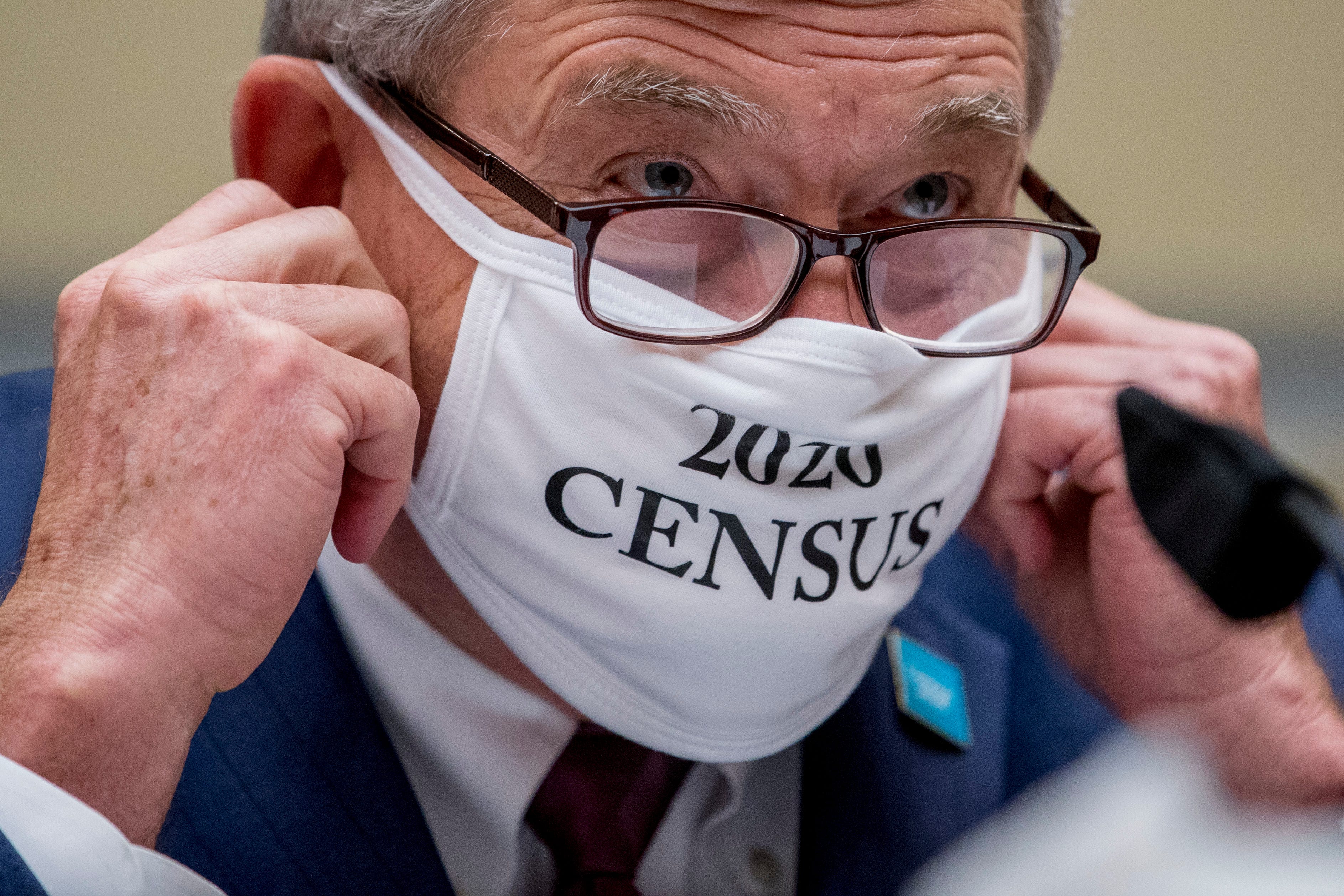

Now the bureau is ending door-to-door operations, which started two months late, a full month earlier than previously announced. Steven Dillingham, the U.S. Census Bureau Director, issued a statement August 3 alluding to health risks that field operations pose.

“The Census Bureau’s new plan reflects our continued commitment to conduct a complete count, provide accurate apportionment data, and protect the health and safety of the public and our workforce,” Dillingham said.

Politicians, advocacy groups and officials, including former Census Bureau directors, have called for reinstating the October deadline to reach more people.

Before COVID-19, the Government Accountability Office had already marked the 2020 Census as “high risk,” a status assigned to programs with potential weaknesses to corruption or inaccuracy. The bureau’s recent decision to halt the count early has only heightened the risk, said J. Christopher Mihm, managing director of strategic issues at the GAO.

“Our concern with changing the date is anytime you have a late design change, it really increases the risks of, in this case, an inaccurate, incomplete census,” said Mihm.

Former Census Director Ken Prewitt put it more forcefully.

“If they want an accurate census, then the deadline has to be extended,” Prewitt said in an interview. “The Census Bureau is not in charge, the White House is not in charge, Congress is not in charge. COVID is in charge.”

Major disruptions

USA TODAY’s analysis was based on demographic information from the Census Bureau’s annual American Community Survey and self-response rates provided on the bureau’s website.

The bureau cautioned against comparing 2010 rates to 2020 rates because of changes in how the census is conducted. But Ong said such comparisons give an accurate picture of changes that occurred in 2020 taken as a whole -- including the pandemic.

“I believe that the comparison does provide useful insights,” he said.

The coronavirus has made the 2020 census dramatically different from the one administered a decade ago, starting with last spring’s national shutdown. It upended plans for delivering census questionnaires to about 1 in 20 households.

While most homes receive either a mailed form to fill out or a letter inviting them to respond online, a small number concentrated in the west and south can’t easily get mail. Bureau employees with address binders deliver questionnaires to these homes by hand.

In 2010, the home deliveries began March 1 and reached 12.5 million homes in a month.

This year, the bureau was two weeks into the drop offs when COVID-19 quarantines forced census operations to a halt March 18.

More: Coronavirus slows search for census workers

The Census Bureau eventually restarted the hand deliveries and finished by August. But response rates in areas with a lot of hard-to-reach households were 20% below the previous census, according to Ong, the UCLA professor. By comparison, tracts requiring no in-person drop offs were only 3% below their 2010 rates, said Ong, who has previously served as an adviser to the census bureau.

Meanwhile, community outreach groups that help drive response had to curtail their efforts because of the coronavirus.

Fernando Garcia, the Executive Director of the Border Network for Human Rights, said his organization has not been able to visit more rural communities in Texas as its leaders had hoped.

“When COVID came, it vaporized our strategy,” said Garcia. “Outside El Paso and in southern New Mexico, some of these regions are so isolated.”

More: Groups 'pulling out all the stops' to accurately count people of color

Communities of color have also suffered higher rates of COVID-19 infection and death than among white people.

The failure to reach these kinds of households in person seems to have taken the biggest toll on responses from families with limited internet access.

In tracts where more than 90% of households have broadband, response rates increased slightly from a decade ago, when the census was conducted entirely by mail. The simplified online process conceivably mitigated whatever pandemic distractions might keep people from mailing in a paper form.

But nationwide about one in every six households lack internet access. In tracts where less than 60% of households have high-speed internet access, response rates have fallen 16% since the last census.

That digital divide has particular implications for minority communities.

In tracts with the fewest broadband subscriptions, people of color typically comprise about 75% of the population. In a typical tract with extensive high-speed internet use, the situation is reversed: about 73% of residents are white.

And, in fact, minority neighborhoods abandoned the census this year disproportionately, USA TODAY’s analysis found. Tracts whose population was overwhelmingly white typically trailed their 2010 response rates by only 2%. For tracts with high percentages of Black residents, the typical share of households answering the census dropped 11%. In highly Latino tracts, the drop was 15%.

One reason Latinos may be more reluctant to answer the census than in years past, advocates say, are the policies of Donald Trump. Garcia, the Border Network director, said the president has bred an environment of fear.

“In every instance, we saw how this administration was undermining efforts instead of promoting participation of marginalized communities,” Garcia said. “In the minds of many people, they feel the risk that their information is going to be used for immigration purposes.”

By law, census responses cannot be used against respondents and personal information cannot be shared, even with law enforcement agencies. The Census Bureau reiterated that fact when asked whether Trump’s order has made it harder to reach undocumented households.

But such messages aren’t always enough to overcome immigration fears, according to Garcia, whose organization says its goal is to improve border communities’ civil rights with the goal of equal political, economical and social conditions for all.

More: Where are the noncitizens? Trump administration wants to know down to the block level

“The attack against these communities by the administration I think is very intentional,” he said. “They don’t want immigrants to be counted.”

The final count

The bureau still has four weeks to do in-person visits. But the effort will last less than two months instead of three in 2010, and the number of door-knockers hired was 330,000 as of late August, versus 600,000 last decade.

Although initial census responses were down in certain tracts, the bureau said overall more Americans than expected answered the census on their own. That plus new electronic tools unavailable in 2010 have reduced the follow-up workforce needed, the bureau said.

More: Michelle Obama, Tom Hanks and other celebs urge Americans to answer census

Ong, the UCLA researcher, said in an email that it will be hard to even out inequities in who wasn’t counted this time.

“The large and growing racial and income differences have a rippling effect downstream for other operations, creating more challenges and hurdles,” Ong said.

The City University of New York’s “Hard to Count” website shows the percentage of households initially answering the census, plus those counted by any means, including follow-ups. The Census Bureau has highlighted the bigger numbers to indicate progress.

But the CUNY site noted potential problems with information gathered during the follow-up operation, concluding that the bureau’s enumeration rates “on their own do not tell us about the quality or accuracy of the count.”

The Census Bureau’s own review of the 2010 census found that, compared to forms that households submitted without further prodding, information from in-person visits was more likely to have errors or lack all necessary information.

Bureau officials did not directly respond when asked what steps they would take to correct any lopsided counts of families in 2020. Instead, the agency noted in a statement to USA TODAY that it estimates each decade’s undercount by using a follow-up survey. But the process only quantifies the error rather than fixing it.

The bureau said it historically has “imputed” missing data from neighborhood characteristics and other data sources. Imputation added 1.2 million people to the national count in 2010, for example.

The bureau’s latest timeline calls for apportionment counts -- which set the number of seats each state gets in the U.S. House of Representatives -- to reach the president’s desk December 31, 2020, instead of a previously planned April 30, 2021.

That reduces time for the bureau to scour the data for accuracy, from five months a decade ago to three months this year.

“Anything from how a city decides where to put a traffic light or where to open a new school is driven by census data,” said Terry Mannis, senior director of census and voting programs at Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

Mannis said getting reliable numbers has immediate urgency.

“With accurate census data,” Mannis said, “we can actually prove where resources need to be deployed across the country in response to the pandemic.”

USA TODAY data reporters Mark Nichols and Mike Stucka contributed.