Inside the deadliest mass overdose in St. Louis history

All told, 11 people overdosed on fentanyl-tainted crack cocaine at Parkview and Park Place apartments.

In February, Parkview Apartments was the scene of the deadliest mass overdose in St. Louis history. // Photo by Theo Welling

This story originally appeared in St. Louis’ Riverfront Times. It has been syndicated with permission. Please support our Missouri sister-publication however you can.

On February 5, St. Louis Metropolitan Police officers began following the trail of the deadliest mass drug overdose in St. Louis history.

It was a cold, bright Saturday morning when they entered Parkview Apartments number 1015, at 4451 Forest Park Avenue.

Police discovered five people: Three were passed out, but still clinging to life. Two others, men ages 57 and 61, had already died, according to city police reports.

All had smoked crack cocaine tainted with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid painkiller up to 100 times more powerful than morphine.

At about noon the same day, police found the body of a man who had overdosed in nearby Park Place Apartments at 4399 Forest Park Avenue.

Ninety minutes later, police once again entered Parkview and took the elevator to the 14th floor, then hustled to apartment 1413. There they found the bodies of two more men who died from fentanyl poisoning, police records show.

Just after midnight the next day, and only three doors down, police discovered the lifeless body of a 54-year-old man in apartment 1416. An hour later, they found a 57-year-old man who had collapsed outside the 14th-floor elevator.

The final fatality was a woman, 54, whose body was discovered around 2 p.m. on February 7 in apartment 1424, police records show.

During this three-day window, dozens of St. Louis police and firefighters swarmed the building to look for new overdose victims as 911 call followed 911 call.

A woman who lived in the building and didn’t wish to be identified told the Riverfront Times she first heard about the overdose deaths after waking up from a nap on February 5 and talking to a relative on the ground floor.

“The relative said, ‘They just found three bodies,'” she recalls. The next morning, her relative gave her an update: “‘They found five,’ and I’m like, ‘Oh, my God.'”

Sirens blared morning and night that weekend.

“Man, listening to it was so scary,” says the woman who has since moved out of Parkview. “It was like, ‘Oh, my God, we were living in a movie. … It started to almost become normal to see these people — they were just wheeling bodies out.”

A man who asked to be identified as J.J. has lived on Parkview’s 14th floor for many years. He said the floor was flooded with police throughout that February weekend.

“They came in like they did a raid,” J.J. recalls. “They came to my door. Bam. Bam. Bam. I jumped out of my bed. They said, ‘Anybody else in there with you?’ I said, ‘No, it’s just me.'”

Most of those who died had lived or hung out on Parkview’s 14th floor. Each was well known and liked by other apartment residents.

“They were super-nice, super-sweet,” the ex-tenant says. “You’d always see them in the hallways at some point, like downstairs in the front.”

The overdose deaths that weekend included a man nicknamed Freckles, a frequent 14th-floor visitor. He lived with his mother in a nearby apartment house.

There was Re-Re, a big woman who used a wheelchair and Calvin, who had long supported himself as a house painter and handyman.

And there was Andre, a University City High School graduate who, according to a family friend, had been sober and drug free for years before relapsing the day of his passing. Andre had been an amateur boxer in his youth, along with his older brother, Robert, who spoke proudly of him at his memorial service in late February.

“I was a lefty,” Robert told mourners during a service shared on YouTube. “He was a righty.”

All told, 11 people overdosed on fentanyl-tainted crack cocaine at the Parkview and Park Place apartments between February 5 and 7 — resulting in eight deaths. All the victims were Black and were between the ages of 43 and 61.

It is the second-deadliest opioid overdose event in U.S. history but the deadliest such event in St. Louis.

The deadliest single fentanyl overdose cluster in American history happened just a week before, in late January, when nine people died from consuming fentanyl-tainted crack cocaine bought from a dealer in Washington, D.C.

Despite the high death toll, that mass overdose event received almost no national attention.

Also escaping any national attention was a mass overdose event on February 20, when six people overdosed—five fatally—in a single apartment in Commerce City, Colorado, after consuming what they believed was pure cocaine, but which in fact was fentanyl.

Two weeks later, another mass overdose event flew under the media radar on March 4, when 21 people overdosed — three of them fatally — at a homeless shelter in downtown Austin, Texas, after ingesting crack cocaine and methamphetamine laced with fentanyl.

A mass overdose event that did make national headlines, however, occurred on the same day in March. Six people — including five West Point cadets, among them a member of the military academy’s storied football team — overdosed on fentanyl-laced cocaine while on a spring-break trip to Florida. None died.

Like the victims of the Parkview mass overdose in St. Louis, the people who overdosed in Washington, D.C.; Texas; Colorado; and Florida apparently had no idea they were consuming drugs laced with fentanyl.

The growing number of unsuspecting people ingesting fentanyl has led to a nationwide spike in deadly mass overdose events like the one at Parkview.

It’s a worsening trend that led the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration to issue an urgent nationwide bulletin in early April.

“In just the past two months, there have been at least 7 confirmed mass overdose events across the United States resulting in 58 overdoses and 29 overdose deaths,” the bulletin states. “Many of the victims of these mass overdose events thought they were ingesting cocaine and had no idea they were ingesting fentanyl.”

The bulletin also includes this harrowing statistic: “Last year, the United States suffered more fentanyl-related deaths than gun-related deaths and auto-related deaths combined.”

In the 12-month period ending in October 2021, more than 105,000 Americans died from drug overdoses with two-thirds of those deaths caused by fentanyl and other synthetic opioid painkillers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Here in Missouri during the same period, almost 1,900 Missourians — a new record — died from drug overdoses, with the vast majority stemming from fentanyl, according to Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services data.

The fentanyl crisis has hit St. Louis with special ferocity. Figures show the city’s overdose mortality rate is 48 per 100,000 people. It is even higher for Black males in St. Louis city, according to Missouri Institute of Mental Health figures.

Physicians have used fentanyl for decades as a painkiller and anesthetic, but always closely watched patients who were administered the drug.

It causes “wooden chest syndrome,” which is characterized by extreme tightness in the chest muscles, airways and the diaphragm. Up until only a few years ago, fentanyl was relatively rare as a street drug. But now it is so ubiquitous and cheap that it has virtually replaced heroin in St. Louis and many other large cities.

Today fentanyl poses an extreme danger to all users of illicit drugs because it is commonly added as filler to crack cocaine, methamphetamine and to imitation pharmaceutical drugs known as counterfeit drugs, says Assistant Special Agent in Charge Colin Dickey, head of the DEA’s St. Louis regional office.

The DEA is trying to stop fentanyl and other illicit drugs from coming into America from China — where the precursor chemicals to make it are cheap and readily available — and Mexico, where criminal gangs smuggle it across America’s southern border.

The quantities crossing the border can be staggering. Police in late June seized 150,000 fentanyl pills — worth an estimated $750,000 — from a car during a traffic stop in Central California.

Through its national One Pill Can Kill program, the DEA is also warning community groups about the dangers of fentanyl mixed with other drugs. The counterfeit pills are manufactured by overseas drug networks and are made to look identical to prescription medications such as OxyContin, Adderall, Percocet, Vicodin and Xanax.

The DEA estimated in a May report that 40 percent of counterfeit pills contain potentially fatal doses of fentanyl. Adderall is one of the most popular black-market pills, thanks to college kids trying to focus while studying for exams.

Mass overdose events like the one that hit Parkview Apartments are likely to recur, according to Dickey.

“As long as the situation stays as it is, I think we do anticipate we could potentially see mass overdose events like this in the future,” he says.

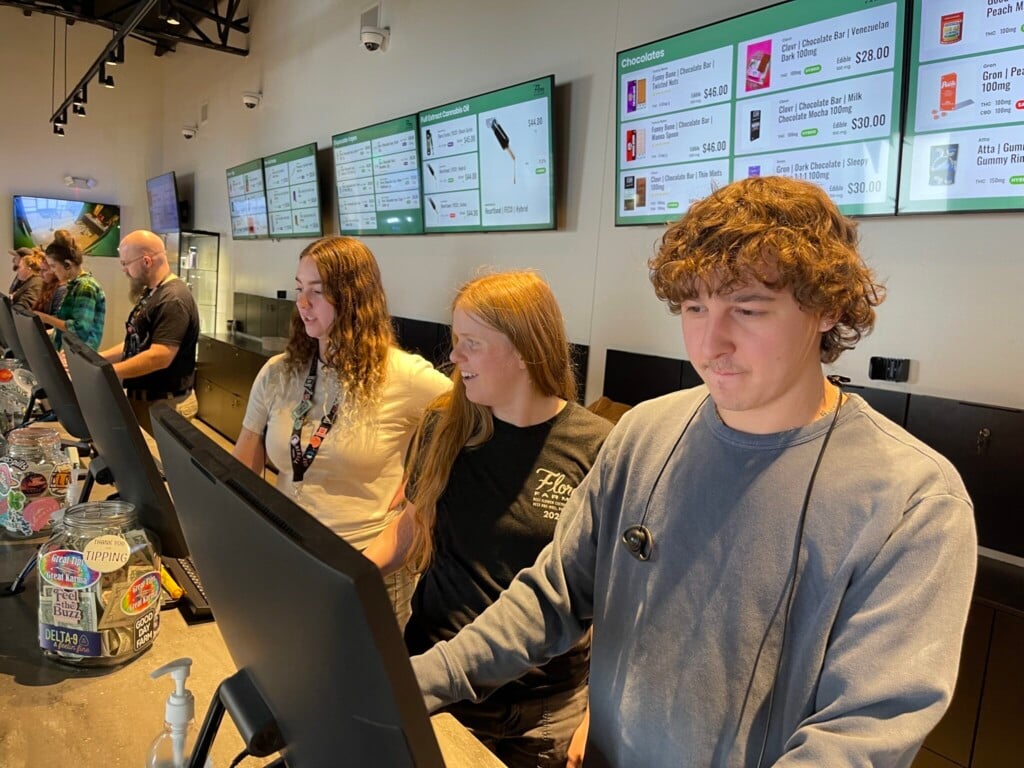

Danielle Reed says that her mother, Chuny Ann Reed, did not rock up the cocaine that led to the mass overdose. // Photo by Mike Fitzgerald

Chuny Ann Reed, 47, used to live on the 14th floor in Parkview Apartments. Now, she awaits trial at the Pulaski County Detention Center, in Ullin, Illinois, about 155 miles southeast of St. Louis. She faces federal charges of distribution of cocaine base and of fentanyl resulting in serious bodily injury. If convicted, she faces at least 20 years in prison, according to federal charging statements filed February 8 in the U.S. federal court in St. Louis.

So far, Reed is the only person charged in connection with the Parkview mass overdose event, and she has pleaded not guilty to the charges.

Reed has not been charged in connection with either the Parkview deaths or the Park Place fatality. No one has yet publicly suggested how fentanyl contaminated the crack cocaine that Reed allegedly sold from her Parkview apartment.

Like many substance users, Reed — who for years used both heroin and fentanyl — long supported herself by selling drugs, according to federal documents and people close to her.

Reed’s first criminal conviction occurred in December 1997, when she pleaded guilty in St. Charles state court to a felony charge of cannabis possession. Court records do not show how much jail time, if any, she received.

A year later, Reed was convicted in St. Louis state court of two charges: illegal possession of cocaine base (crack) and a controlled substance. She was sentenced to three years in a state prison but was released in July 2001, court records show.

By 2019, Reed had moved into Parkview with her teenage daughter Emily. By all accounts, theirs was a low-key existence.

Neighbors describe Reed as friendly and quiet.

“We never had any problems or confrontations,” J.J. recalls.

“We spoke a couple times,” the ex-tenant quoted earlier says. “Actually, she wanted me to do her hair.”

Problem was, Reed seemed high all the time, but would ask, “‘Can you do my hair like this?'” the woman says. “I was like, ‘Talk to me when you’re sober.'”

One of the survivors of the February 5 mass overdose admitted to DEA agents that he regularly bought crack cocaine from Reed “for approximately two years,” according to a federal affidavit filed in Reed’s federal court case.

Surveillance video showed a Black male entered “Reed’s apartment and stayed for several minutes,” according to another DEA affidavit. “He then departed and returned directly to his apartment. Later in the day, this individual was discovered dead inside his apartment from an apparent overdose. At the scene of the overdose death, investigators recovered and seized a crack pipe with trace amounts of a suspected controlled substance inside the pipe.”

Diane Dragan, Reed’s federal public defender, declined to comment on the federal affidavits.

Danielle Reed, 30, is the oldest of Chuny Ann Reed’s four children.

Danielle acknowledges her mother has used drugs for a long time.

“But my momma, she didn’t hurt people,” says Danielle, who describes the lengths her mother would go to in order to care for her younger sister Emily, a teenager who is severely disabled with cerebral palsy.

“She’s loving, caring,” Danielle says of her mother. “Everybody who do drugs is not a bad person.”

I met Danielle on a Saturday morning in early May at her apartment off Jefferson Avenue, a short distance northwest of the Lafayette Square neighborhood. I was joined by a Dutch journalist named Merijn de Waal, who covers the United States and South America for his newspaper, NRC Handelsblad, of Amsterdam.

De Waal had contacted me a few months earlier from his home base in Amsterdam after finding articles I’d written about the opioid crisis in St. Louis.

De Waal wanted to write about the Parkview overdose deaths to help his readers understand America’s surging drug overdose crisis — by far the worst in the developed world, according to the United Nations and other health watchdogs.

De Waal was in St. Louis for a weeklong visit to do some reporting, so we found our way to Danielle Reed’s place.

Reed acknowledged during our interview that her mother is a longtime substance user.

“And was she only using crack or also other stuff?” de Waal asked.

“My momma didn’t do crack,” Danielle said.

“What did she do?”

“Heroin,” Danielle said.

Fentanyl has all but replaced heroin in the St. Louis area. “There is no heroin in St. Louis,” he said.

“Well, fentanyl,” Danielle amended.

Danielle said her mother would never have intentionally mixed the fentanyl with the crack cocaine that led to so many overdoses. Someone else must be responsible for the fentanyl getting added to the cocaine.

“My mom doesn’t know how to make the powdered shit,” she said.

According to Danielle, the person who could make the crack cocaine base was her mother’s boyfriend, who has not been arrested.

“I’m 100 percent and then some,” she said. “My momma did not rock that shit up. She don’t know how to do it. And I’m 100 percent sure I know he did it, and I know my momma’s taking the fall for him.”

“Did she tell you?” de Waal asked.

“I just know,” she said, shaking her head. “It was totally an accident. The people at Parkview, they know her. They love her. She is a good person. My momma don’t hurt people intentionally.”

Parkview Apartments is home to nearly 300 tenants when at full capacity. It stands just off the heart of the Central West End neighborhood — three blocks east of Forest Park, and a few blocks north of Barnes-Jewish Hospital, the Washington University medical campus and the thriving Cortex area.

Before COVID-19 hit in March 2020, current and former tenants described the apartment complex, which is owned by the St. Louis Housing Authority, as a reasonably safe and clean place.

But over the last couple years the quality of life at Parkview has declined, according to tenants and to 17th Ward Alderwoman Tina Pihl, who took part in two town-hall-style meetings with tenants in late April.

Tenants complained about cleanliness, especially problems with bed bugs, the closure of the building’s community room, and building managers who ignored complaints, Pihl says.

“One of the issues … is there hasn’t been accountability,” she says.

Another major issue was water leaks in the apartment. The ex-tenant quoted earlier said she went to management five days in a row to complain about leaks in her apartment, and only after the fifth day did anything get done.

“Y’all don’t care about the people, and it shows,” she says.

In the months since the Parkview deaths, the St. Louis Housing Authority has worked with the Habitat Company of Chicago, which manages the complex, “to enhance the current systems and has contracted with a new security company,” according to a statement released by Indira Murray, a housing authority spokeswoman.

What’s more, “The Habitat Company’s on-site team members are prepared to assist in addressing the most severe opioid abuse concerns,” the statement goes on.

The housing authority works with regional agencies to provide services to residents. These include mental-health and drug-counseling services. The housing authority even partnered with the People’s Community Action Corporation to provide onsite resources for Parkview residents.

As for complaints about insects and water leaks, Murray says the housing authority meets regularly with the Parkview Tenants Affairs Board and “therefore is aware of some of the resident complaints at Parkview Apartments. Working with Habitat Management, we have immediately addressed those complaints.”

Murray further notes the housing authority has received approval to begin several capital projects, including repair of the parking lot and replacement of all elevators. The authority has also submitted a grant application to upgrade the building’s safety and security, according to Murray.

As a result of the Parkview mass overdose, 17th Ward Alderwoman Tina Pihl has started working with experts at nearby Saint Louis University to improve living conditions and set up a pilot opioid harm-reduction program.

Ideas for the harm-reduction program began forming in the wake of an April 30 listening sessions held at Parkview and nearby Cortex.

“The biggest thing is we were able to give them a voice,” Pihl says. “My goal is to take this initiative and make it happen. A lot of times people listen but nothing happens.”

Harm reduction, according to many experts, is the only strategy capable of reducing the number of fentanyl-related overdose deaths.

Examples of harm reduction include proactively distributing Narcan — a drug that revives unconscious opioid overdose victims — in neighborhoods with histories of substance use; handing out fentanyl test strips; and performing free chemical analyses of street drugs, like what’s already being done at the Mo Network in St. Louis.

Pihl says that the earliest her ward’s pilot program could launch is six months from now. A big problem that must be addressed is what to do with people who get into opioid treatment and complete it but wind up back in the neighborhoods where drugs like fentanyl are plentiful.

“Are we putting them back into the environment … without resources?” she asks.

The St. Louis Fire Department has already started some harm-reduction efforts. Three years ago, it started carrying boxes of Narcan on all its pumper trucks and vehicles driven by battalion chiefs, according to Dennis Jenkerson, the city fire chief.

But fentanyl’s hold is so powerful that many revived victims — despite their close brushes with death — go out and immediately get high again, Jenkerson says.

“We hit them with the Narcan, and within 20 seconds they’re looking at you and they’re all upset because you just messed up their high,” Jenkerson says. “And they walk away. We can’t handcuff them and keep them there until a health-care worker gets there.”

The overdose epidemic has reached the point where Jenkerson has joined efforts calling for the city to invest in something he would never have considered even a few years ago: controlled-use centers, where substance users can have their street drugs tested for fentanyl and then use them safely under supervision. Users would also be encouraged to seek treatment and be provided with help to obtain it.

“I’m not 100 percent sure that controlled centers are the way to go,” Jenkerson says. “But you got to try something. … You can’t do the same things over and over and expect different results.”

Carolyn Reed holds an image of her daughter, Chuny Ann Reed and granddaughter Emily, who has cerebral palsy. // Photo by Theo Welling

On his sixth day in St. Louis, de Waal and I visit Parkview to talk to tenants. After a couple hours we walk to his rented Mini Cooper, get in and drive the four miles north to the home of Chuny Ann Reed’s mother.

While he guides his rented car along Grand Boulevard, I ask de Waal — a man paid to think and write about America — what is going on with this country during what seems like a fraught moment in its history.

I note that experts have blamed America’s drug-overdose crisis — like its gun-violence problems — on runaway capitalism, as well as the loneliness and alienation that afflict many, especially men.

“Where is America headed?” I ask.

“They say every big empire has a lifespan of 250 years,” de Waal replies. “If you start counting from 1776, you have four years left.”

He looks at me and laughs.

A few minutes later we park in front of a modest brick house in the Mark Twain neighborhood.

Carolyn Reed is seated on the front porch. Even though we show up unannounced, she is welcoming and invites us to join her.

Reed acknowledges that her daughter Chuny Ann Reed is a longtime substance user.

Parkview was not a good place for Chuny Ann, her mother says, especially during the pandemic.

“I went there during the pandemic,” Carolyn says. She remembers seeing a lot of drug users. “They were roaming real tough there. They might be isolated, but they’re going to get what they need and go home.”

Chuny Ann Reed’s finances took a hit three years ago when it was suspected that her daughter Emily — who is severely disabled with cerebral palsy — had been exposed to fentanyl. That led the state of Missouri to take custody of Emily, according to Carolyn.

De Waal wonders if Reed started selling crack cocaine after losing the state financial assistance she had once received to pay for Emily’s living expenses.

“She wasn’t able to pay the rent?” he suggests.

“She was always doing something,” Carolyn says. “She didn’t sit back and be supported by Emily’s check.”

Carolyn warned her daughter to stay out of trouble, she says.

“‘Don’t be doing nothing you might get caught up in,'” she recalls of the advice she gave. “‘If you do it, do it by yourself. Don’t have your friends and you.’ That’s my daughter’s problem. When she did be sociable, she was too sociable.”

A follow-up story from Riverfront Times covers the surprising turns that the case took next.

Mike Fitzgerald is a journalist who lives in St. Louis. He can be reached via Twitter @MikeWearAMask.