The highlight of the social calendar in Paradise is Gold Nugget Days, a fair that celebrates its 19th-century Gold Rush origins and has been held every year since 1959. This year the tradition continued, as locals paraded in wild west period dress and set up stalls selling clothes, plants and honey in a lush community park.

There was one big difference, though. The manicured lawn was a lonely island of normalcy amid a landscape of char and ash.

Held last weekend, it was the first Gold Nugget festival since the wildfire that leveled Paradise and killed 85 people, making it America’s deadliest in a century. Tomorrow there will be another bittersweet landmark. It has been six months since the fire, and it has become clear that the town will not spring back to life and pick up where it left off at 6.30am on 8 November.

“I still just want to go home, and not home the place but home a moment in time,” said Trisha Wells, 41, who was a cardiac neurology technologist at the largest employer in town, Adventist Health Feather River. In February, the hospital announced it would not reopen. Wells has moved to Virginia, and other Paradisians have scattered across the country, from Hawaii to Alaska and Maine.

Situated on a wooded perch in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains in northern California, Paradise was a town of 27,000 living in rambling homes and trailer parks. You could rent an apartment for $850, and the affordability and peacefulness lured people priced out of the San Francisco Bay Area.

“A little non-destination town that’s not on the way to anything important,” Paradise native Krystalynn Martin wrote in a widely circulated poem after the fire. “It’s just that end-of-the-road town where people settle and know each other and roots run deep.”

On 8 November it was swept by flames that consumed, at one point, approximately 200 football fields of vegetation per minute, killing dozens of seniors, people with disabilities, and those who were simply trapped. More died in the aftermath, from the smoke and the stress. The fire destroyed more than 18,000 structures, including about 14,000 homes, or 90% of those in the town.

People are living in the seemingly random structures that escaped the inferno, and businesses such as Dutch Bros Coffee and Attic Treasures Mall have reopened. The first home rebuild permit was approved in late March, but widespread construction has been prevented because the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema) has mandated that toxic debris must first be cleared, and the water supply in town is contaminated with benzene, a cancer-causing chemical. It cannot be used even for cooking or brushing teeth.

Enrollment has fallen by more than 50% in the Paradise school district, and students have dispersed to schools throughout the county for the remainder of the school year. There are hopes that Paradise high students will be able to graduate on their own campus, which survived, this month.

Events like Gold Nugget Days are as important for getting Paradise going again as opening its schools, said Rick Silva, editor of the Paradise Post, which has published without pause since the disaster. “If you don’t have it then you lose the momentum for next year,” he said as he surveyed the scene in the community park. He estimated there were only one-third as many attendees as usual.

There was a donkey race and a parade featuring bagpipers and ceremonial shotgun firings, though it was far shorter than normal. By 3pm the fair in the park was becoming deserted, despite the fact the event wasn’t scheduled to end for another hour.

“I wish I would’ve grabbed my home videos, my jewelry,” a woman wearing a “Moving Forward” pin told friends she’d bumped into.“If I’d just grabbed those I could have dealt with everything else.”

She added: “One thing about not having a lot of furniture, you don’t have to dust very much.”

Climate and fire experts are asking questions with vast implications. Just before stepping down as the head of CalFire, California’s wildfire agency, in December, Ken Pimlott said the state should consider banning home-building in areas vulnerable to wildfire – just like Paradise continues to be.

In a recent interview with the Associated Press, however, the California governor, Gavin Newsom, had a different message, evoking tradition and continuity. “There’s something that is truly Californian about the wilderness and the wild and pioneering spirit.”

Six months after the fire, those affected recall how they survived the destruction and what happened to them next:

Trisha Wells, 41, medical technologist: ‘It’s gone and we can’t go back’

I was on the phone with a patient saying, “I don’t think you should come in today, it’s getting kind of smoky,” when the boss ran into the building and said the hospital was on fire. Nobody was panicking. We made sure everyone was evacuated before we left. I went out into the parking lot with my co-workers and I gave them hugs. Everybody said, “OK guys, be safe,” and that was the last I saw them. And I’ll probably never see them again.

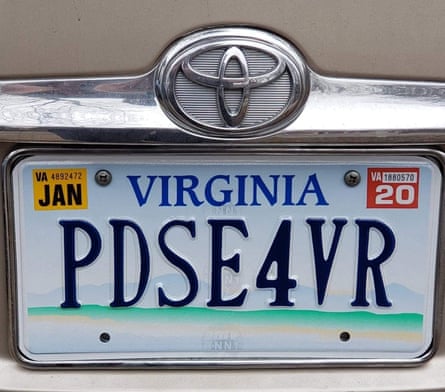

I have not been back. It was very apparent right away that there wasn’t going to be anywhere to go close by, so my husband’s best friend lives in Midlothian, Virginia. He said, “I’ve got this big house, plenty of room, why don’t you guys come and stay with me until you figure it out?”

I’m homesick and I’m grieving. Even though my family is OK I just feel like I can’t believe it’s all gone. And I couldn’t give a crap about my house – I don’t care about my bed, TV, computer, any of that stupid stuff. It’s like every day you think of something you cannot replace. My husband’s grandmother painted this stupid lamp, and we called it the Ugly Lamp, because it was hideous. But she’s gone and now it’s gone and we can’t get it back.

It’s still really surreal. It just feels like you’re gonna wake up and and it’s gonna be a dream.

Jason Buzzard, 33, realtor: ‘You don’t get to be part of a new build of a town very often’

My wife Meagann and I really started three days after 8 November calling contractors and getting the ball rolling. We didn’t really sit down and say, “Hey do you want to rebuild, do you want to move?”, we just knew that was what we were going to do.

After the fire we were living in a trailer for two months until we got a rental. You can do that camping for about a week but when you have to share it with two other people and three dogs at the same time trying to work and figuring out school for the kid, it’s just complete madness. It was pretty emotional, especially since no one was allowed to go back into Paradise for a month.

When they called us and let us know they were gonna be issuing us the first rebuild permit, that was exciting. Now the time for mourning the loss of our house and all our stuff is over and it’s time to move forward. Paradise is where we both grew up and seeing it building back up from ashes is going to be a good thing. You really don’t get to be part of a new build of a town very often. I’m not worried about fires in the future.

Mary Nieland, 68, owner of Attic Treasures Mall: ‘Business is better than ever’

As soon as the open sign came on, people were here. They were just looking for something to be open, anything. I really didn’t expect anybody. Some of my vendors thought there was no hope. They thought there would be no money, no customers, that our town would be abandoned.

The day they lifted the evacuation, I came back and started cleaning my house. We had no electricity in town, so I would come up early in the morning while I had good light. We had no water. I just used bottles, cleaners and rags and started cleaning and I did the same here at the store. It took five weeks. I cried every time I came up. For five weeks I cried. You couldn’t help it. It’s hard to see the town that you were born and raised in burn like that and see all the lives that it devastated – knowing every house and every building meant something to somebody.

It’s just special. Why would such a beautiful special place burn the way it did? It’s almost like Paradise was sent to hell. Like the devil couldn’t stand it that we were so happy here.

I’ve got three new antique vendors moving in that were in the other shops. They needed a place to go. I’m inviting to all the other shops in here to start over. Business is better than ever – people want to support our town. Paradise is coming back, no question. It may take a long time, but it’s going to be beautiful.

Robert Edwards, 53, senior engineer: ‘The town of Paradise dying broke my mother’s heart’

We found my mother, Barbara Allen, two days after the fire. Ninety-four days later she passed. The town of Paradise dying, it broke her heart. I don’t think she had the will to live after that. There was nothing else for her. She loved it that much, she really did. This is where she wanted to be.

After the fire she came up with me to Washington, and I went back to work and tried to get our lives together. I took her to my doctor for some blood work and it was really just not good. We saw the oncologist, and the oncologist said: “You have a 10x10x6 centimeter mass. It looks like it has moved into the liver. It also looks like it could be in your kidneys.”

I asked her many, many times: can I tell people? She told me not to and said: “People don’t need to see my pain.” When we told everyone what happened to her, people started sharing all these stories about her. All these people loved her. They said she did everything possible for them.

Everybody in town knew her. She was involved with everything: cribbage and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. She ran the senior center for years; she got funding from the federal government to serve breakfast and lunch there. If Paradise comes back, I’m going to help rebuild the senior center. We’ll put her name on it.

Alastair Gee and Dani Anguiano are writing a book about the fire. For updates, follow them on Twitter: @alastairgee and @Dani_Anguiano