The peyote cactus is central to many of the rituals of the indigenous Huichol tribe of Mexico. The bright colors and dreamy symbols of their yarn paintings are said to be inspired by the hallucinations experienced by ingesting the mescaline-rich plant in shamanic rituals.

“They do these beautiful creations with beads, paint and sculpture. [By taking] peyote they say they communicate with the gods for the design. I respect that,” says Mauricio Sulaimán, the Mexican-born president of the World Boxing Council [WBC].

It’s a statement that may help explain the WBC’s recent and, some may argue, unlikely partnership with Wesana Health, the Chicago-based biotech company that is developing psychedelic medicine for the treatment of repetitive traumatic brain injury.

For a governing body whose own Clean Boxing Program demands random drug testing of all of its fighters even the slightest association with a substance still classed as an illegal narcotic by the US government is quite a move. For Sulaimán though, the decision was simple.

“We have so little knowledge of what’s in the brain, so you have to be open to find ways to make boxing and sports safer [and] what can be used to cure,” he says.

The word “cure” is Sulaimán’s optimistic shorthand for the development of any treatment for the brain injuries that have blighted boxing for its long and bruising history. And for a man who has spent his life in the company of those putting their head in harm’s way, the experience of such mental degradation was all too familiar.

“Tommy Hearns struggles with his speech these days. I spent many, many intimate moments with Muhammad Ali, but the memory that sticks out is Raúl ‘El Raton’ Macías,” Suleimán says, of the man considered by many as Mexico’s first boxing idol.

“We were at the dinner for our induction into the Boxing Hall of Fame. And in the middle of eating, he stood up and he said: ‘I’m going home now. I’m going to walk home.’ You know, he lived in Mexico City and we were in New York.”

It was his personal experience around those with brain trauma that made the story of Wesana Health’s CEO Daniel Carcillo all the more compelling to Suleimán.

Carcillo was known as the Car Bomb during his time as an NHL player, so tough was he on the ice. But a career that saw him win two Stanley Cups with the Chicago Blackhawks also delivered countless concussions and subconcussions. So much so that in 2015, at the age of 30, he retired with symptoms including slurred speech, headaches, memory loss, extreme light sensitivity, depression and suicidal ideation. Things only got worse after his skates were put to one side.

“I just couldn’t control or understand what was happening to me,” Carcillo says.

Three weeks into planning how to take his own life he decided to try psilocybin, the active ingredient found in magic mushrooms, for the first time. Under supervision he took a high dosage that allowed him to confront the trauma in his life.

From the brink of suicide, Carcillo says he is now symptom free, the life-changing nature of his psychedelic treatment providing inspiration for the business he co-founded last year. By taking advantage of new laws in some states of America that have legalized psychedelics for medicinal use, Wesana hope to develop a prescription drug that could help treat degenerative brain conditions suffered by athletes.

There are caveats, of course. After all, Carcillo has good reason to talk up his own story of recovery, especially given the recent flotation of Wesana on the Canadian stock exchange. And with a theoretical product which, at best, is years away from entering the marketplace, what’s to say his good health isn’t down to a placebo effect which the WBC has cynically jumped on to be portrayed in a more caring light?

“His recovery sounds viable and doesn’t surprise me,” says Matthew W Johnson, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University and an associate director of their world-leading center for psychedelic and consciousness research. “In our controlled trials, success rates look really good. It’s not uncommon for the people in our sessions to have life-changing experiences with long-lasting effect.”

As one of the most published scientists on the effects of psychedelics, Johnson explains the medicine is potentially working on two levels.

“There’s depression and addiction treatment … where a number of published studies have shown psychedelic treatment to be extremely promising in comparison with SSRIs like prozac. The other category, though, is neurological.”

Johnson explains studies like those conducted by the University of California, have found psychedelic treatments to induce neuroplastic effects in brains of rats.

“Their brains seem to be rewiring and healing,” he says of the exploratory work that has not yet been tested on humans.

While Johnson is careful not to encourage any use of psychedelics outside of research environments, or to suggest their ability to rebuild brains is anything other than theoretical, he remains excited by the potential the future offers.

“I think it’s viable and worthy of more scientific exploration. Psilocybin is going to be approved for depression treatment, within the next five years, or maybe less, in my opinion,” he says. “I think it could be a revolution in psychiatry, though it’s not going to be for everyone.”

One of those it may never appeal to is Sergio “The Latin Snake” Mora. Typical of many fighters, he was careful about what he put inside his body during his boxing career.

“I don’t even like taking Advil,” says Mora, who retired from boxing in 2020. “I grew up that way: didn’t drink soda. Now, you might tell me it’s a mushroom, it’s a natural plant that grows but I still won’t take it. I smoked pot one time when I was 13 and I said, what the hell was that?”

Pain became something to manage during his 36-fight career, according to Mora, who remembers urinating blood on more than one occasion after bouts where he’d taken shots to the body. And it’s this attitude, so hardwired in fighters, that often makes treatment of mental health challenging. In the United States, this is often exacerbated by the fact that few fighters have medical insurance to cover regular heath examinations.

It demonstrates the challenge even a powerful body like the WBC might have in changing the minds of its members.

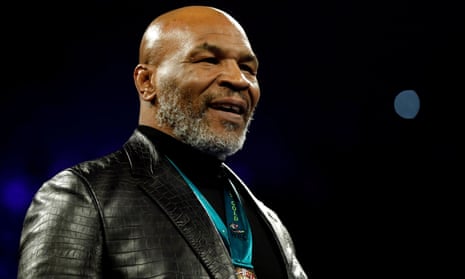

Wesana hope that recruiting one of the greatest fighters of all time, Mike Tyson, as an advisor to their board may help with this task.

“I believe if I’d been introduced to the benefit of psychedelics for therapeutic use early in my professional career, I would have been a lot more stable in life,” Tyson told the Guardian via email. “I had a lot of public outbursts and they were all mental illness related. Prescription drugs meant I didn’t feel like myself but with psychedelics I feel I’m a happier, lighter version of me.”

It’s a sentiment that resonates with Carcillo, who struggled to explain his own symptoms to loved ones when he retired.

“One thing that not a lot of people talk about is supporting the families of former fighters. Understanding these symptoms, and understanding that your spouse does not want to be this way. Offering them support is something that we’re passionate about, too,” he says.

Tyson says psychedelics have helped ease the blows he took in the ring and during sparring session but other greats like Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson died suffering the mental effects of their beatings. But Tyson may prove to be the first of many boxing veterans who take part in psychedelic studies in the future.

“We can help former fighters by inputting them into clinical trials, understanding more about how subconcussive and concussive impacts affect pathology … and the psychological ailments that many athletes suffer,” says Carcillo. “Not just post-event, but with programs that will focus on human performance aspect too; how much we can get out of these monkey suits of ours.”

For Sulaimán, Carcillo’s progressive plans complement the WBC’s three-decade-long, multimillion dollar funding of UCLA’s world-leading concussion and head trauma research.

“We have the boxers ready to participate,” he says. “We have our medical committee and research teams ready. So we’re just waiting to see what were all these leads.”

The shamans of the Huichol tribe would surely approve.