One day in 1961, an American economist named Daniel Ellsberg stumbled across a piece of paper with apocalyptic implications. Ellsberg, who was advising the US government on its secret nuclear war plans, had discovered a document that contained an official estimate of the death toll in a preemptive “first strike” on China and the Soviet Union: 300 million in those countries, and double that globally.

Ellsberg was troubled that such a plan existed; years later, he tried to leak the details of nuclear annihilation to the public. Although his attempt failed, Ellsberg would become famous instead for leaking what came to be known as the Pentagon Papers – the US government’s secret history of its military intervention in Vietnam.

America’s amoral military planning during the Cold War echoes the hubris exhibited by another cast of characters gambling with the fate of humanity. Recently, secret documents have been unearthed detailing what the energy industry knew about the links between their products and global warming. But, unlike the government’s nuclear plans, what the industry detailed was put into action.

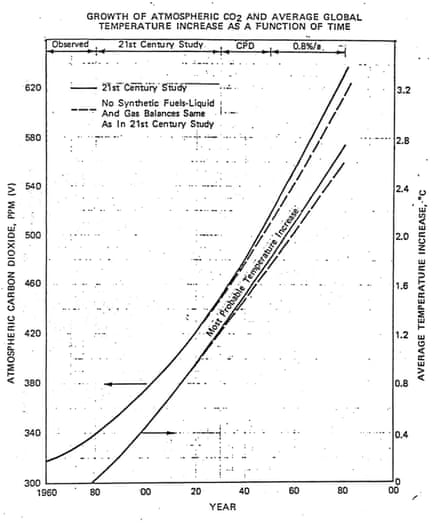

In the 1980s, oil companies like Exxon and Shell carried out internal assessments of the carbon dioxide released by fossil fuels, and forecast the planetary consequences of these emissions. In 1982, for example, Exxon predicted that by about 2060, CO2 levels would reach around 560 parts per million – double the preindustrial level – and that this would push the planet’s average temperatures up by about 2°C over then-current levels (and even more compared to pre-industrial levels).

Later that decade, in 1988, an internal report by Shell projected similar effects but also found that CO2 could double even earlier, by 2030. Privately, these companies did not dispute the links between their products, global warming, and ecological calamity. On the contrary, their research confirmed the connections.

Shell’s assessment foresaw a one-meter sea-level rise, and noted that warming could also fuel disintegration of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, resulting in a worldwide rise in sea level of “five to six meters.” That would be enough to inundate entire low-lying countries.

Shell’s analysts also warned of the “disappearance of specific ecosystems or habitat destruction,” predicted an increase in “runoff, destructive floods, and inundation of low-lying farmland,” and said that “new sources of freshwater would be required” to compensate for changes in precipitation. Global changes in air temperature would also “drastically change the way people live and work.” All told, Shell concluded, “the changes may be the greatest in recorded history.”

For its part, Exxon warned of “potentially catastrophic events that must be considered.” Like Shell’s experts, Exxon’s scientists predicted devastating sea-level rise, and warned that the American Midwest and other parts of the world could become desert-like. Looking on the bright side, the company expressed its confidence that “this problem is not as significant to mankind as a nuclear holocaust or world famine.”

The documents make for frightening reading. And the effect is all the more chilling in view of the oil giants’ refusal to warn the public about the damage that their own researchers predicted. Shell’s report, marked “confidential,” was first disclosed by a Dutch news organization earlier this year. Exxon’s study was not intended for external distribution, either; it was leaked in 2015.

Nor did the companies ever take responsibility for their products. In Shell’s study, the firm argued that the “main burden” of addressing climate change rests not with the energy industry, but with governments and consumers. That argument might have made sense if oil executives, including those from Exxon and Shell, had not later lied about climate change and actively prevented governments from enacting clean-energy policies.

Although the details of global warming were foreign to most people in the 1980s, among the few who had a better idea than most were the companies contributing the most to it. Despite scientific uncertainties, the bottom line was this: oil firms recognized that their products added CO2 to the atmosphere, understood that this would lead to warming, and calculated the likely consequences. And then they chose to accept those risks on our behalf, at our expense, and without our knowledge.

The catastrophic nuclear war plans that Ellsberg saw in the 1960s were a Sword of Damocles that fortunately never fell. But the oil industry’s secret climate change predictions are becoming reality, and not by accident. Fossil-fuel producers willfully drove us toward the grim future they feared by promoting their products, lying about the effects, and aggressively defending their share of the energy market.

As the world warms, the building blocks of our planet – its ice sheets, forests, and atmospheric and ocean currents – are being altered beyond repair. Who has the right to foresee such damage and then choose to fulfill the prophecy? Although war planners and fossil-fuel companies had the arrogance to decide what level of devastation was appropriate for humanity, only Big Oil had the temerity to follow through. That, of course, is one time too many.

Benjamin Franta, a former research fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, is a doctoral candidate at Stanford University, where his research focuses on the history of climate science and politics.

An earlier version of this piece, entitled “Global Warming’s Paper Trail”, was published on Sept. 12, 2018 by Project Syndicate.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion