Galaxy Brain Is Real

Looking at the long views from the Hubble space telescope might be good for you.

In December of 1995, astronomers around the world were vying for a chance to use the hottest new tool in astronomy: the Hubble space telescope. Bob Williams didn’t have to worry about all that. As the director of the institution that managed Hubble, Williams could use the telescope to observe whatever he wanted. And he decided to point it at nothing in particular.

Williams’s colleagues told him, as politely as they could, that this was an awful idea. But Williams had a hunch that Hubble would see something worthwhile. The telescope had already captured the glow of faraway galaxies, and the longer Hubble gazed out in one direction, the more light it would detect.

So the Hubble telescope stared at the same bit of space, nonstop, for 10 days—precious time on a very expensive machine—snapping exposure after exposure as it circled Earth. The resulting image was astounding: Some 3,000 galaxies sparkled like gemstones in the darkness. The view stretched billions of years back in time, revealing other cosmic locales as they were when their light left them and began coasting across the universe.

“I still love looking at that image,” Williams told me earlier this year, as Hubble celebrated its 30th anniversary in space.

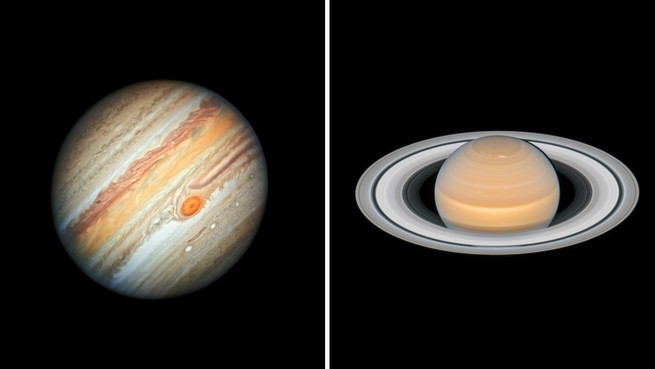

Hubble, the most powerful telescope in orbit, is still producing dazzling observations of targets near and far, from the familiar planets of our solar system to the mysterious suns of other worlds. The mission might be one of the easiest scientific endeavors to maintain in the middle of a plague. When I visited Hubble’s mission-operations center in Maryland last December, only one person sat inside the control room, all the staff that was needed to manage the mostly automated telescope—and, it would turn out three months later, when the state reported its first COVID-19 case, the right number to avoid tangling with a virus that thrived in close quarters.

Hubble has quite a clear view of the universe from its perch in orbit, away from the atmosphere that warps and blocks cosmic light from beyond. Its images are, to use a very nonscientific word, pretty. You don’t have to be an astronomer, or to know that the galaxy you’re gazing at is called NGC 2525, in order to appreciate them. These images can serve as momentary distractions, small bursts of wonder, and they might even be good for the mind. At a time when the coronavirus has shrunk down so many people’s worlds, Hubble can still provide a long view—a glimpse of places that exist beyond ourselves.

Imagine yourself at a scenic vista somewhere on Earth, such as the rim of the Grand Canyon or the shore of an ocean stretching out past the horizon line. As your brain processes the view and its sheer vastness, feelings of awe kick in. Looking at a photo is not the same, but we might get a dose of that when we look at a particularly sparkly Hubble picture of a star cluster. The experience of awe, whether we’re standing at the summit of a mountain or sitting in front of a computer screen, can lead to “a diminished sense of self,” a phrase psychologists use to describe feelings of smallness or insignificance in the face of something larger than oneself. Alarming as that may sound, research has shown that the sensation can be a good thing: A shot of awe can boost feelings of connectedness with other people.

“Some people do have the sense when they’re looking across millions of light-years, that our ups and downs are ultimately meaningless on that scale,” says David Yaden, a research scientist in psychopharmacology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and who has studied self-transcendent experiences, including in astronauts. “But I think [space images] can also draw our attention to the preciousness of local meaning—our loved ones, people close to us, this Earth. It’s not a leap that I think always occurs, but I think the benefits flow to people who do make that leap."

The experience is like a miniature version of the “overview effect,” the mental shift that many astronauts have experienced after seeing Earth as it truly is, a gleaming planet suspended in dark nothingness, precious and precarious. Astronauts have put this feeling into some lovely words over the years, but few have described it as succinctly as the Apollo astronaut Edgar Mitchell, who saw Earth from the moon in 1971: “You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it.”

Most of us aren’t astronauts, and we’ll never see “the big picture” quite like that. On Earth, photos from a giant orbiting telescope, capturing the grandeur of the cosmos, are as close as we can get. The appeal of these images is durable enough that a website called Astronomy Picture of the Day has been running since 1995, the year Hubble reached into a dark void and plucked out glittering treasures. The site looks just as it did 25 years ago, with the no-frills Times New Roman look of the early internet. Robert Nemiroff, an astronomer at Michigan Tech and a co-founder of the website, told me that pageviews are up by about 75 percent compared with last year’s, starting with a spike in April. These visitors didn’t leave behind any clues about their intentions—perhaps people were simply spending more time online, cooped up inside; perhaps they were looking for a jolt of feeling that would shake their perspective out from within the walls of their own home.

That’s the hope of Judy Schmidt, who spends hours each week with Hubble observations. Schmidt, an amateur astronomer, sifts through years-old telescope data and cleans them up, producing radiant images. One of her fortes is brightening shadows that ’90s computer software missed, uncovering previously unseen features. In a way, Schmidt curates the cosmos and hangs them in the ether of the internet, where people can pass through, like museum visitors, and tilt their heads at a particularly impressive bit of space that, for a moment, might make them feel small, but in a reassuring way. “I just hope that their life has improved for even just the few seconds that they took to look at it and they thought, Wow, that’s out there,” Schmidt told me.