How to Save Women’s Lives After Roe

A federal law exists that could protect women having life-threatening pregnancy complications—but only if the Biden administration decides to use it.

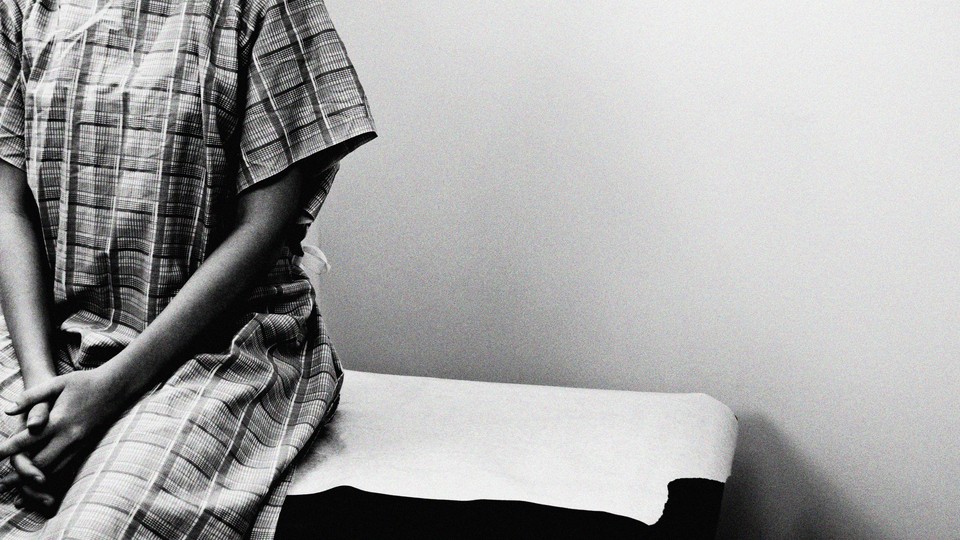

In February, NPR reported a story of a woman, Anna, who went into labor at 19 weeks, far too early for her child to survive outside the womb. This is a condition known as “preterm premature rupture of membranes” (PPROM), and in many cases the medically recommended treatment is abortion. Attempting to delay labor long enough to reach a point where the baby could survive can mean risking infection, sepsis, and death.

Unfortunately, Anna lived in Texas, where the state’s abortion law, S.B. 8, has effectively outlawed abortion after six weeks. As a result, the hospital—and consequently, her doctors—concluded that they could not treat her. They found a provider in Colorado and discussed whether it was safer for Anna to board an airplane or endure a long car trip, given her ongoing medical emergency. They settled on an airplane and developed a plan in case she needed to deliver her baby in the plane’s bathroom.

She survived the flight, made it to Colorado, and had her abortion. But the horrifying reality is that, as awful as this was for her, it could have been far worse.

Anna is far from the only Texan whose life has been threatened by Texas’s strict abortion law. We know of a handful of other cases where Texas patients with PPROM have been forced out of state to get a medically indicated abortion. And other media outlets have reported that Texans with ectopic pregnancies—a nonviable pregnancy that can become life-threatening at any moment—have had to drive 12 to 15 hours out of state to get an abortion when a heartbeat is present.

To be clear: This is how women will die in a post-Roe America. But there is a federal statute that the Biden administration could use to try to save lives.

The law is called the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). It was passed by Congress in 1986 and requires all hospitals with an emergency department that accept Medicare or Medicaid, and the physicians who work at these hospitals, to provide stabilizing treatment to any patient who is in labor or experiencing a medical emergency. The law was originally passed as an anti-patient-dumping statute designed to prevent hospitals from turning away uninsured patients; to do so, it created the obligation for emergency departments to treat medical emergencies regardless of a patient’s ability to pay. But the statute’s obligations go beyond this original purpose, and the Biden administration could use it to create legal risk for hospitals that deny lifesaving abortion care.

Because EMTALA is a federal law, it trumps state laws, including state abortion laws, and its definition of a medical emergency therefore trumps a life-or-health exception in any state abortion ban. Such exceptions in state abortion laws are typically quite narrow and create uncertainty for providers about when the pregnant person’s life is threatened enough to justify an abortion. For example, in the case of ectopic pregnancies, some hospitals and physicians will wait to intervene until after the pregnancy ruptures, causing the mother to hemorrhage and to be at immediate risk of dying, even though this outcome could have been prevented.

EMTALA’s definition of a medical emergency is broader and includes any person in labor or suffering from a condition that, without immediate attention, could be reasonably expected to seriously jeopardize their health, impair a bodily function, or cause dysfunction in an organ. This definition covers many urgent pregnancy conditions, including PPROM, ectopic pregnancy, and complications from incomplete miscarriage or self-managed abortion. Because EMTALA has broader protections for patients and supersedes state law, it can be used to protect patients and their health even in states with extremely restrictive abortion laws.

Under EMTALA, once the hospital has determined that an emergency condition exists, it must provide stabilizing treatment—by law. In many of these medical emergencies that arise in a previable pregnancy, the only way to stabilize the patient is with surgical or medical interventions that will terminate the pregnancy. Though EMTALA does permit hospitals to transfer patients in some circumstances, if the patient is not yet stabilized, they can be transferred only upon patient request or if the medical benefits outweigh the risks. A state law or policy cannot be the justification for an out-of-state transfer.

The Biden administration, through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), issued a memo in response to S.B. 8 that attempted to highlight the obligation of hospitals and physicians to treat patients under EMTALA. But it was ambiguous and tepid. As a result, people like Anna are being denied lifesaving abortion care, and at some point, one of them will likely die, as has happened in other countries.

The Biden administration can and must do more. First, the CMS memo never included the word abortion—a persistent issue in the Biden administration’s communications—causing unnecessary confusion. Rather, it focused on patients “experiencing pregnancy loss.” It’s true that in the cases where EMTALA would apply, a pregnancy loss is in process or inevitable without an abortion, but hospitals could use this language as an excuse to delay abortion care until after the fetus’s heart has stopped. This is not the time to obfuscate. The next communication with hospitals must state with perfect clarity that when a medical emergency is present and stabilizing care would involve an abortion, it must be offered immediately regardless of state law. The Biden administration must also communicate that the failure to adhere to these legal obligations will result in an enforcement action.

Second, the administration must actually enforce the statute. Hospitals and doctors in Texas are currently operating out of fear that they will get sued for providing abortions unless the patient’s condition becomes so dire that death is imminent without it. They are adopting the Catholic-hospital approach: wait and perform the abortion only when the patient is on death’s door. This approach could be replicated in all states that ban abortion, resulting in totally avoidable tragedy.

Hospitals are already preparing for institutional policy changes if state abortion laws change. However, having restrictive policies that are at odds with the EMTALA obligation to stabilize patients leaves doctors in the tenuous position of balancing conflicting laws and policies in real time. Hospitals must understand that any delays beyond medical necessity create legal risk in the other direction as well, unless an informed patient would prefer to wait. Hospitals that permit medically necessary abortions when EMTALA is triggered will be supporting their physicians, instead of leaving them to make these difficult decisions that threaten their medical license and livelihood on a case-by-case basis.

Admittedly, enforcement depends on patients filing complaints. But CMS can make its complaint process more user-friendly and do a better job spreading public awareness of how to file complaints, so that it can act. (Additionally, the Biden administration is not the only mechanism for enforcing EMTALA. Patients can also sue hospitals for breaching their EMTALA duties. But because of the confluence of abortion stigma and the trauma of a medical emergency, many patients will not have the wherewithal to endure the challenges of litigation.)

The post-Roe world will be disastrous and chaotic. EMTALA will not make the overwhelming majority of abortions legal in anti-abortion states or stop the coming parade of horribles. But it could save lives and reduce unnecessary carnage. For it to work as it could, though, the Biden administration needs to wield the statute as a sword. Even in a post-Roe America, no state should be able to scare hospitals into denying lifesaving abortion care.