Gay Men Need a Specific Warning About Monkeypox

Tiptoeing around the issue carries its own risks.

A disproportionate number of cases in the recent monkeypox outbreak have shown up among gay and bisexual men. And as public-health authorities investigate possible links to sexual or other close physical contact at a Pride event in the Canary Islands, a sauna in Madrid, and other gay venues in Europe, government officials are trying hard not to single out a group that endured terrible stigma at the height of America’s AIDS crisis.

“Experience shows that stigmatizing rhetoric can quickly disable evidence-based response by stoking cycles of fear, driving people away from health services, impeding efforts to identify cases, and encouraging ineffective, punitive measures,” Matthew Kavanagh, the deputy executive director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, recently said. For many years, following the outbreak of HIV, the fear of being judged or shamed has dissuaded some gay men from being tested.

But as a gay man who studies the history of infectious disease, I worry that public-health leaders are not doing enough to directly alert men who have sex with men about monkeypox. Gay men are not the only people at risk, but they do need to know that, right now, the condition appears to be spreading most actively within their community. In recent days, CDC officials have been acknowledging this forthrightly. Director Rochelle Walensky noted Thursday that, of the nine monkeypox cases identified in the United States as of midweek, most were among men who have sex with men.

Yet many other well-intentioned officials appear fearful of saying something homophobic, and news outlets have published articles emphasizing that monkeypox is “not a gay disease.” Their caution is warranted, but health agencies are putting gay men at risk unless they prioritize them for interventions such as public-awareness campaigns, vaccines, and tests.

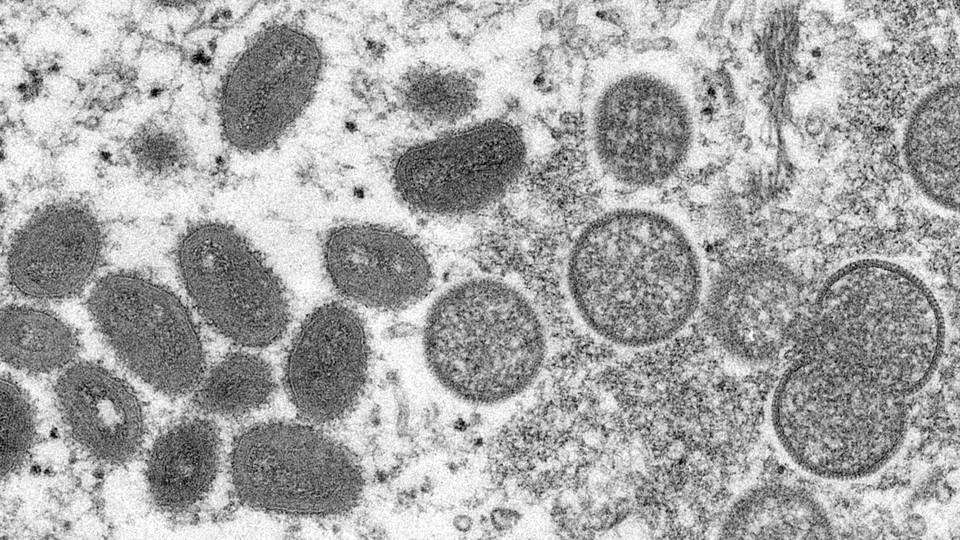

Monkeypox, which is related to smallpox and causes symptoms that include a rash, had not previously been viewed as a sexually transmitted infection, but many people who have contracted the disease recently have exhibited symptoms, such as lesions around the genitals or the anus, consistent with sexual transmission. Public-health officials need to work with gay-community health centers and other LGBTQ organizations to deliver information about monkeypox symptoms to doctors and their patients.

Although gay activist groups and clinics may be carefully monitoring the outbreak, I am concerned about gay men in areas where doctors may be unaware of the pathophysiology of the virus. Therefore, public-health agencies should also press gay social-media apps and other online platforms to tell their users that men who have sex with men have been disproportionately infected by the virus. These outreach efforts should pay particular attention to the most marginalized people who might be at risk. In the past, HIV prevention and treatment efforts reached white men but not the large number of men of color and working-class and poor men who became infected with that virus.

For the moment, both the media and public officials continue to frame monkeypox as rare. I understand the instinct not to overreact. Yet though the number of documented cases remains small, the presumption that the outbreak is an anomaly is precisely what misled medical authorities, journalists, and even gay people themselves 40 years ago, when HIV first entered the headlines. AIDS was routinely framed as an unusual disorder among a small cluster of gay men in San Francisco and New York, but the pathogen that caused it had already circulated far more widely. I worry that we are making the same mistakes we did when HIV first began to surface.

The United States is still dealing with the baggage of the HIV/AIDS crisis. In the 1980s and early 1990s, confusion reigned, and some Americans worried needlessly about having incidental contact or even being in the same room with a person with AIDS. Public-health campaigns tried to ease anxiety by creating subway ads that showed both gay and straight couples kissing to emphasize that HIV didn’t spread that way or talking about condoms to promote safer sex. These efforts were useful; putting out reliable information about how a virus is transmitted, and how it can be avoided, is essential to protecting public health.

However, for fear of stirring up animus against gay men, officials today may be underplaying the role of sexual transmission in recent monkeypox cases.

Viruses spread as a direct result of physical and social conditions. COVID-19 has a greater chance of spreading in a crowded indoor environment than along a hiking trail. Similarly, monkeypox doesn’t require sexual contact but is prone to spread in situations where people with exposed skin are together in close quarters. Like HIV, monkeypox does not check your sexual odometer; the virus doesn’t count the number of partners everyone has and then latch on to those with the largest number. It does seek opportunities to spread—and some queer spaces, particularly where people meet for sex, have created the conditions that allow that to happen.

The premises where gay people congregate closely have helped define the community. When public-health authorities shut down bathhouses during the early days of HIV, many gay people saw the closures as a violation of their growing liberation. (By contrast, in March 2020, when public-health officials shut down movie theaters and stadiums, many Americans were sad to see these venues temporarily close, but they were not essential to anyone’s fundamental identity.) Although I am not suggesting that governments impose restrictions on queer spaces, health agencies ought to tell gay men that monkeypox may indeed be spreading sexually.

Authorities need to be able to send that message without moralizing about patrons’ behavior. Historically, when public health is under threat, the urge to judge and shame has been strong—as both the HIV/AIDS crisis and COVID-19 have shown. Especially before coronavirus vaccines were available, people sharply criticized one another on social media or in person even for harmless behaviors, such as going to the beach or jogging outdoors without a mask.

But both health officials and the public need to be able to differentiate between using a virus to pathologize an entire community and acknowledging that certain physical and social conditions genuinely do pose a higher risk of infection. Giving gay men carefully tailored warnings about monkeypox risk can be a form of education, not a form of stigma.

Rather than treating bathhouses, clubs, and dance parties exclusively as spreaders of infectious diseases, they should be recognized as potential promoters of sexual health. For decades, it was common to find a bucket of a condoms at the entrance of many bars, alongside posters and leaflets with information about safe sex. LGBTQ organizers have ample practice with informing their communities about a possible health threat and championing safe-sex practices.

Public-health officials should activate those resources rather than tiptoeing around the issue. If gay men are at risk from the monkeypox outbreak, we need to be told that explicitly—instead of being told that the condition is rare and mostly happening in other parts of the world.