The United States of Dirty Money

How landlocked South Dakota became one of the world’s hottest destinations for offshore funds.

Over the weekend, a consortium of journalists dropped the latest jaw-dropper of an investigation into the sordid, metastasizing world of offshore finance. Dubbed the “Pandora Papers”—following 2016’s Panama Papers and 2017’s Paradise Papers—the documents revealed a litany of now-familiar offshore-banking and tax-sheltering shenanigans, including the Jordanian king’s nine-figure real-estate purchases, the Azerbaijani dictator’s British investments, and the spiderweb of finance linked to the Kremlin, all built on illicit or ill-gotten gains and roped behind networks of financial opacity.

The Pandora Papers are the biggest batch of revelations to date, including details from nearly 12 million corporate and financial records. In addition to its unprecedented scope, this latest leak had one other key difference. Whereas previous revelations centered on anonymous companies in Central America or Caribbean jurisdictions refusing to halt their offshoring services, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists’s reporting implicated a behemoth that has thus far escaped the kind of scrutiny it’s long deserved: the United States. Offshore once meant far-flung islands beyond the reach of major economies, but the U.S. has brought those same services back onshore—and, in so doing, evolved into one of the world’s greatest havens for financial secrecy.

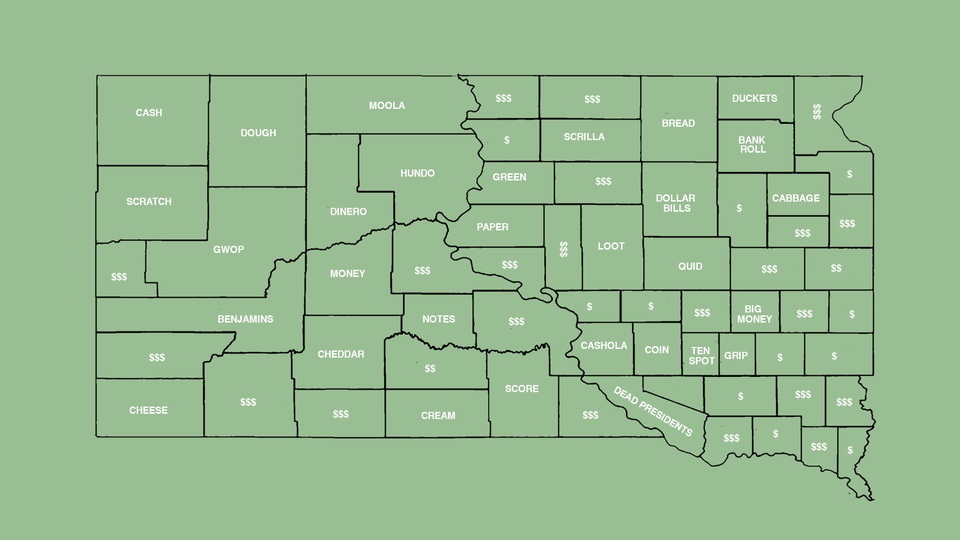

This is a reality, and a trend, that has been developing for decades. Delaware, Nevada, and Wyoming have all spent years marketing themselves around the world as a welcome home for anonymous shell companies, providing legal secrecy and protection to anyone looking to bury their finances away from investigators and authorities. But as the Pandora Papers make clear, another state, South Dakota, has introduced a brand-new tool to pull in as much anonymous wealth as it can, attracting little attention and even less criticism. The ICIJ, which received the leaked data and partnered with news outlets around the world to publish them, identified more than 200 trusts created in the U.S., holding a total of $1 billion in assets. More than 80 of those trusts were in South Dakota—the most of any state.

Thanks to this leak, we finally have an idea of who’s been taking advantage of the state’s legal infrastructure for providing financial confidentiality. The documents reveal that in 2017, Ecuadoran President Guillermo Lasso, a former banker, sheltered assets in a pair of South Dakota trusts—only three months after Ecuador passed legislation barring politicians from using tax havens. In another example, family members of Carlos Morales Troncoso, the former vice president of the Dominican Republic, moved millions in assets into South Dakota trusts, along with shares controlling the country’s largest (and most controversial) sugar-production facilities. As The Guardian wrote, the Pandora Papers show that South Dakota “is sheltering billions of dollars in wealth linked to individuals previously accused of serious financial crimes.” Not all of the money is linked to kleptocrats, oligarchs, and shady politicians. But it’s clear that South Dakota trusts are a magnet for the kind of dirty money that corrupt leaders around the world have spent years trying to hide.

And yet the 200 trusts detailed in the ICIJ’s reporting are but a drop in the far larger ocean of money sloshing around in South Dakota’s financial institutions. The Pandora Papers estimate that South Dakota trusts now host some $360 billion in anonymous, untraceable assets. Other estimates put the figure at nearly $1 trillion—all of it stowed in, as the journalist Oliver Bullough recently noted, “probably the most potent forcefield for wealth available anywhere on earth.”

According to South Dakota law, these trusts—formed as a result of state leaders looking to capitalize on growing global demand for financial anonymity, create jobs, and generate revenue—are regulated and legal. That description also applies to Delaware shell companies, anonymous Nevada corporations, and anonymous real-estate and private-equity investments—and although it is technically true, it doesn’t mean the underlying funds were legally acquired in the first place. (As the saying goes, the scandal isn’t what’s criminal, but what’s legal.)

South Dakota trusts provide precisely the kind of anonymity that clients are looking for. Not only can those establishing trusts list themselves as beneficiaries—contradicting the original purpose of a trust, which is to shield assets for others—but they don’t even need to visit the state to set one up. The state prohibits sharing information about these trusts with other governments, and any court documents pertaining to South Dakota trusts are kept private in perpetuity. More important, South Dakota pioneered regulations that allow its trusts (which typically expire after a century or so) to remain in place forever, forming the bedrock for dynastic wealth.

State officials say they’re keeping a close eye on any signs of questionable figures or finance flocking to the state. “We’re certainly always worried about the black eye of one nefarious actor, one money-laundering or white-collar crime, that somehow utilized our trust industry to commit wrongful acts,” says Tom Simmons, a trust-law expert at the University of South Dakota and a member of the state’s Trust Task Force, which helps steer the state’s pro-anonymity legislation. “It’s not the Wild West.”

In a sense, though, that’s precisely what it is. The Wild West technically had regulations on its books too—not that they stopped the railroad barons and crooked bankers from bending local laws to their own will, devastating communities along the way. Which is what the entire offshoring world, including South Dakota, has been doing on a progressively global scale.

So what should be done about all this? Although the U.S. has made significant headway in recent months when it comes to shell-company transparency, it’s continued to drop the ball regarding transparency for other financial entities. These include the anonymous, perpetual trusts South Dakota has spearheaded, but that’s hardly the only industry profiting from America’s evolution into the world’s greatest offshore haven. Real estate continues to be the country’s biggest sponge for anonymous, ill-gotten wealth, while hedge funds and private equity have ballooned in recent years to offshore destinations of their own. Along the way, America’s art market, auction houses, and luxury-goods dealers have all gotten in on the action—aided by the American lawyers, consultants, and accountants who can work with as much dirty money as they want, thanks to a range of loopholes and exemptions.

The U.S. is long overdue for an overhaul of its entire approach to stopping money laundering. As revealing a glimpse as the Pandora Papers provide, the ICIJ’s reporting represents a narrow slice of the suspicious wealth flowing directly into the heart of the American financial system—all of it looking to be hidden from prying eyes, and in many cases laundered, right here in the United States of Anonymity.