Why Are We Closing Schools?

Keeping kids out of the classroom will make recovering from the pandemic harder in the long term, while not keeping us any safer in the near term.

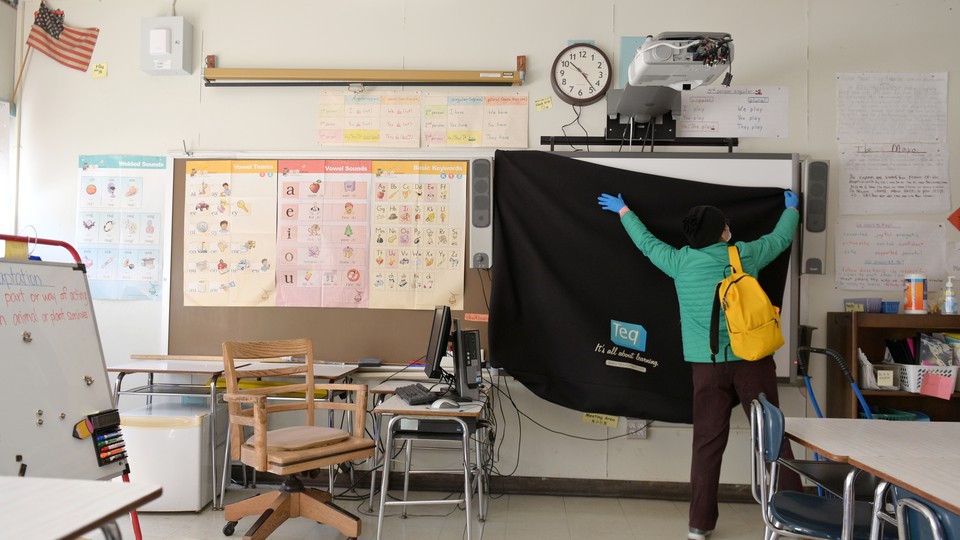

A quarter of New York City’s 1.1 million public-school students have attended in-person class this academic year. Now they will all be learning from home. New York City schools have closed once again as COVID-19 cases rise in the city. The closures could last for weeks or months, depending on the percentage of positive coronavirus cases.

Keeping students home is unnecessary. Reopening schools doesn’t appear to meaningfully increase the level of risk faced by teachers or students, but closing them causes well-documented damage to students. Evidence from around the world—and even from New York City—shows not only that many schools should remain open, but that officials should take more steps to open up classrooms.

Many school districts, including New York City’s, have already implemented a number of measures to keep students, teachers, and their families safe: blended learning, active screening for illness, universal mask wearing, and increased ventilation, among others. These precautions are working, and all the early data show that classrooms do not appear to drive transmission of the virus.

In fact, American schools could reduce their distancing requirements, allowing more students and teachers to return to the classroom. The current six-feet rule in schools, as outlined by the CDC, is almost double the most recent World Health Organization recommendation of one meter, or 3.3 feet. Keeping students six feet apart means some schools don’t have enough space to accommodate all the students who want to attend in-person, and others don’t have enough teachers.

Six feet is also more than most European countries require. In some parts of Switzerland, children are not required to distance while at school, though staff and students 12 and older must wear masks. Even as Switzerland reintroduced rigid national restrictions in early November, its classrooms have remained open with no changes to the distancing requirement. England has also reopened schools and done so without a universal distancing or mask requirement. Its government has implemented other safety measures: Children are kept in distinct groups throughout the school day, and arrival and pickup times are staggered.

Norway and Spain have imposed age-based distancing rules for students over 13 and 9 years old, respectively—but still mandate less than six feet. Italy and Portugal both recommend keeping students and adults three feet apart. Likewise, France, which has returned to national lockdown, recommends distancing of three feet and masks in schools for students 6 years and older.

What public-health institutes, including the United Nations University International Institute of Global Health, where I worked on a report on distancing in schools, have observed from these countries’ data is that school reopenings have not increased the level of transmission in the communities they serve. Child-to-child transmission in the classroom is uncommon, and children in school settings are not the primary transmitters of COVID-19 to adults.

New York City’s own data on its partial reopening show similar results: Schools reflect the prevalence of the virus in the community, but do not drive community spread. According to New York City government data provided to me (I served as a resource for the school district in an informal, unpaid capacity), the city performed more than 74,000 tests in 1,224 schools during a three-week period in October, and just 45 students and 63 staff members tested positive. The percent of students and staff estimated to have had COVID-19 during this period is nearly 40 percent lower than the estimate for the general New York City population for the same period. In other words, both teachers and kids are at less risk of getting COVID-19 in school than they are elsewhere in their day-to-day lives.

Following the data, schools can clearly be reopened safely. Officials must pair that evidence with another well-known fact: Keeping schools closed causes countless children to fall behind. Numerous studies demonstrate the negative effects of being out of school for younger and older children—including a widened achievement gap, mental-health issues, increases in violence and abuse, and even early pregnancies. When schools closed in some Gulf states during and after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Maria in 2017, as many as one in five students never returned. Long-term remote learning, despite being well intentioned, likely isn’t sufficient to meet the needs of a large majority of students. Going to school is far more than a tutorial on the assigned material; it is a process of learning and socializing, in which schools provide children and adolescents with other services and support, including meals, physical-exercise programs, health care, and mental-health services.

Keeping kids out of the classroom will make recovering from the pandemic harder in the long term, while not keeping us any safer in the near term. That is why New York and other districts need to open schools and then take steps to enable families and teachers who want to go back full-time to do so. This requires reducing the physical-distancing requirement for desks while keeping vigilant about other safety measures. The experience from European schools demonstrates that this can be done without putting teachers or students at additional risk.

Even with case numbers climbing in New York City, we know that schools are not driving the pandemic. However, one thing is clear with COVID-19: Our kids are paying the highest price.