How Trump Masks His Incoherence

Many of the president’s statements are difficult to decode—so why doesn’t that concern his supporters?

The 2020 presidential race is a contest between two old men. Neither Trump, 74, nor Joe Biden, 77, has quite the same verve that he did 25 years ago, which comes as no surprise—if Biden wins, he will become the oldest president to take office, eclipsing the mark set by Trump.

The president and his supporters have painted the former vice president as senile or suffering from dementia. In a Pew Research Center poll from August, three in 10 Biden supporters flagged his age and health as a concern about him. But Trump’s age and health didn’t even crack the list of his backers’ top concerns. So how has Trump, who has sought to make Biden’s age and capabilities an election issue, managed to deflect concerns about his own performance?

Biden does sometimes sound old on the campaign trail, and he’s had a few head-scratching moments, but for the most part, he speaks cogently. Trump, by contrast, appears vigorous and energetic, but many of the things he says are incoherent.

During a trip to Wilmington, North Carolina, last week, President Donald Trump said—well, it’s a little unclear what he said. Here’s a transcript:

If you get the unsolicited ballots, send it in and then go, make sure it counted, and if it doesn’t tabulate, you vote. Just vote. And then if they tabulate it very late, which they shouldn’t be doing, they’ll see you voted and so it won’t count. So send it in early and then go and vote, and if it’s not tabulated, you vote, and the vote is going to count. You can’t let them take your vote away. These people are playing dirty politics—dirty politics. So if you have an absentee ballot, or as I call it a solicited ballot, you send it in, but I would check it in any event. I would go and follow it and go vote—and everyone here wants to vote—the old-fashioned way.

By the next morning, Trump was trying to clean up the mess with a Twitter thread in which he told voters to cast a mail ballot, then go to their polling place to make sure their vote had been counted, and only to cast a ballot in person if it had not—advice that not just contravenes the advice of the North Carolina State Board of Elections, but was also an admission that what he’d said the day before didn’t match reality.

Some observers interpreted Trump’s remarks as an invitation to commit felony fraud—evidence of his lawlessness. Others interpreted it as Trump trying to test the system. Still others saw it as just another odd comment from an unhinged president. What’s most striking about the transcript, though, is that his intention is impossible to determine. And the statement is typical of Trump’s public comments—he frequently struggles to express himself clearly.

This is hardly new. Many of the most controversial statements of Trump’s presidency have required interpretation, or at the very least left some substantial ambiguity. He appeared to tell NBC’s Lester Holt that he fired FBI Director James Comey over the “Russia thing,” but he didn’t fully connect the thought, and later denied it. His defenders have insisted that his notorious description of “very fine people” on both sides of a violent August 2017 white-supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, was meant to exclude the neo-Nazis, a deeply implausible but not impossible reading. After Trump appeared to endorse injecting bleach to fight the coronavirus, his defenders again said he’d been referring only to using UV light inside the body (a different idea, but one experts also rejected as dangerous).

The bigger problem comes from comments that are not merely ambiguous but impossible to clearly interpret. Consider this passage, one of several head-scratchers from a briefing on COVID-19 in February, before the disease had spread to much of the U.S.:

I don’t think it’s inevitable. It probably will. It possibly will. It could be at a very small level or it could be at a larger level. Whatever happens, we’re totally prepared. We have the best people in the world. You see that from the study. We have the best-prepared people, the best people in the world. Congress is willing to give us much more than we’re even asking for. That’s nice for a change. But we are totally ready, willing, and able to—it’s a term that we use, it’s “ready, willing, and able.” It’s going to be very well under control. Now, it may get bigger. It may get a little bigger. It may not get bigger at all. We’ll see what happens. But regardless of what happens, we’re totally prepared.

The United States was not, in fact, totally prepared, and reading that remark, it’s not hard to guess why: The president seems to have no idea what he is talking about.

As the progressive journalist Dan Froomkin writes, one reason Trump’s incoherence attracts relatively little attention is that press coverage tends to summarize Trump’s statements and (attempt to) distill meaning from them. The president’s raw quotations take up space and are unlikely to make much sense to readers, so why print them? The problem is that encourages an impression that Trump is more coherent than he is.

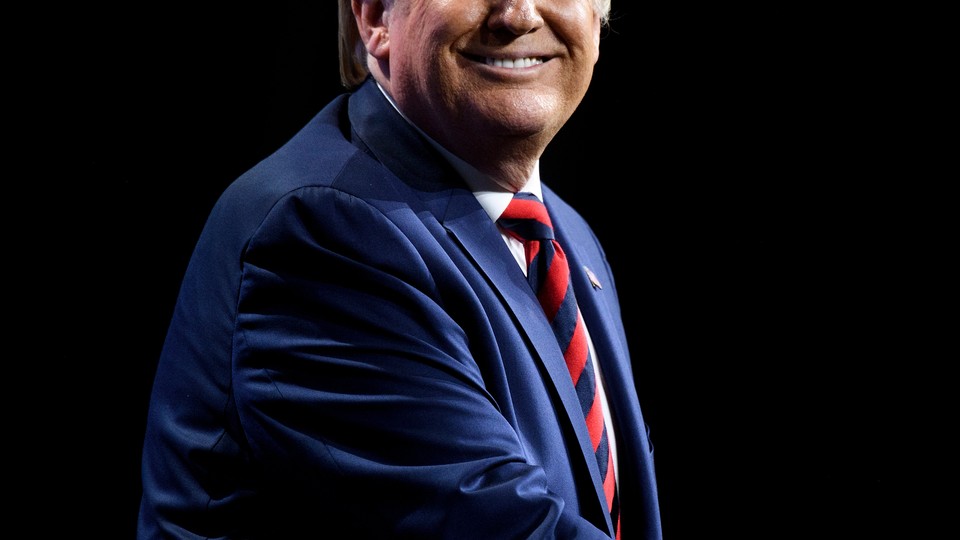

Figuring out what Trump might be trying to say tends to be easier when you watch him. Almost no one speaks in carefully organized paragraphs, but facial expressions, pacing, tone, and gesticulations can help you decode what someone means. Trump is an extreme case: Watch him speak, and you can at least tell roughly what he’s talking about; it’s only when you try to figure out precisely what he means and look at a transcript that you are likely to see how hollow the core is.

There’s one more thing that helps cover up Trump’s incoherence, which is his energetic speaking style. The president is not a good speaker, per se—there’s a reason Stephen Miller drew ridicule when he pronounced Trump “the best orator to hold [his] office in generations”—but he is a transfixing one. His “low energy” insult stuck to Jeb Bush in the 2016 GOP primary not only because of Bush’s laid-back demeanor but because of Trump’s own animation. “The most accurate way to predict reaction to a debate is to watch it with the sound turned off,” my colleague James Fallows wrote in 2016. Trump not only grasps that truth, but he probably does better if voters aren’t listening too closely—or at all. Because he looks and sounds vigorous, his meandering sentences recede from focus.

To prove this point, consider what happens when Trump’s words are divorced from images of Trump. The virality of the comedian Sarah Cooper, who has made a series of videos in which she painstakingly lip-synchs Trump’s words, is premised on the absurdity of the pronouncements themselves. In 2017, the comedian and late-night host John Oliver made a similar point by having an actor read Trump’s words, underscoring their incoherence.

Putting an impressive facade on a shoddy edifice is the story of Trump’s pre-political career, too. Commentators mock his orange complexion and apparently artificial tan, his hair style, and his hair coloring, and they do look faintly ridiculous, but they also serve their purpose—they make him seem younger. Biden must relate, at least a little: His own locks look much fuller than they did 35 years ago, a fact that Politico in 2008 attributed to hair transplants.

Given the importance, and success, of creating this impression of vigor, it’s no wonder that Trump has reacted so fiercely to questions about his health this summer and fall. In June at West Point, Trump seemed to struggle to drink a glass of water and descend a ramp. Matt Drudge spread a video from July in which Trump seemed to be dragging his leg. When a New York Times reporter’s book said Vice President Pence was on standby to take over the duties of the president during a mysterious trip by Trump to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center last year, Trump fiercely denied having a series of mini-strokes—though the book had made no such allegation. Trump’s denial only fed speculation. As I have written, speculative, long-distance diagnoses about Trump’s health are beside the point. Whatever the cause for impairment, it’s the president’s ability to do his job that matters most.

Biden, too, has clearly lost a step. He’s always been prone to gaffes; his 1988 presidential campaign collapsed after he attributed a story from the British politician Neil Kinnock to his own family. He’s also long been meanderingly loquacious, and Evan Osnos reports that when Barack Obama chose him as a running mate, he said, “I want your point of view, Joe. I just want it in 10-minute increments, not 60-minute increments.” But, as Paul Ryan learned in an affable but inexorable demolition in the 2012 vice-presidential debate, Biden can also be quick on his feet. During the 2020 Democratic primary debates, however, he sometimes seemed hesitant or even dazed. The nadir came in September, when Biden was asked what should have been an easy question about the legacy of slavery and delivered this 254-word enigma:

Look, there’s institutional segregation in this country. And from the time I got involved, I started dealing with that. Redlining, banks, making sure we are in a position where—look, you talk about education. I propose that what we take is those very poor schools, the Title I schools, triple the amount of money we spend, from $15 to $45 billion a year. Give every single teacher a raise to the equal raise of getting out of the $60,000 level. No. 2, make sure that we bring in to help the teachers deal with the problems that come from home. The problems that come from home. We need—we have one school psychologist for every 1,500 kids in America today. It’s crazy. The teachers are—I’m married to a teacher; my deceased wife is a teacher. They have every problem coming to them. We have to make sure that every single child does, in fact, have 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds go to school—school, not day care, school. We bring social workers into homes with parents to help them deal with how to raise their children. It’s not that they don’t want to help; they don’t know quite what to do. Play the radio, make sure the television—excuse me, make sure you have the record player on at night, the phone—make sure that kids hear words, a kid coming from a very poor school—a very poor background will hear 4 million words fewer spoken by the time they get there.

The president’s allies held this up as evidence that Biden is too incapacitated for the presidency, but the irony was that the answer resembled nothing so much as a Trump remark. It was all there: the garbled facts, the non sequiturs, the half-completed sentences and abrupt left turns, the inability to make a point.

Biden has taken a low-key approach to campaigning for most of the pandemic, which the Trump campaign has presented as evidence of his fade. But Biden has also taken questions from reporters and spoken to supporters, and in August he rode a bike through his neighborhood, a photo op that showed his own physical fitness and underscored the unlikelihood of Trump casually pedaling around.

The two candidates’ respective convention speeches showed the risks of Trump’s senility strategy. Trump set the bar low for Biden’s performance, suggesting he couldn’t be coherent, but the former vice president’s speech at the Democratic National Convention was crisp and effective, easily clearing Trump’s test. The president’s address at the White House, however, was long and dull. He read it off a teleprompter with little enthusiasm, as if it was the first time he’d seen the text. He even garbled the central line, saying he “profoundly” accepted the nomination, rather than “proudly” accepting it, as his prepared remarks indicated.

Trump’s statements have long been incoherent, a fact his vigorous delivery has often helped mask. But if he continues to deliver nonsense in such a lethargic manner, he’s likely to face the sorts of questions he’s trying to raise about his opponent, himself.