The Surprising Ease of Buying Fentanyl Online

To get extremely potent opioids, users turn to the dark web—and sometimes, Google.

Five or six times a day, a man from Texas injects a dose of carefully measured fentanyl. He does it when he wakes up and before he goes to work, and sometimes on breaks. It makes him drowsy, but he says people can’t usually tell he just used.

He gets his supply the way other people buy books and Bluetooth speakers: He orders it online, then waits for it to come in the U.S. mail. (I was connected to this man through a researcher on the condition of anonymity, out of concern he would be jailed if discovered.)

Researchers say the internet is a surprisingly common method of obtaining fentanyl, an opioid that is now responsible for more overdose deaths than heroin or prescription painkillers. Far from the shady, street-corner deals of popular imagination, more and more drug buys are taking place online, often with the help of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies for added anonymity.

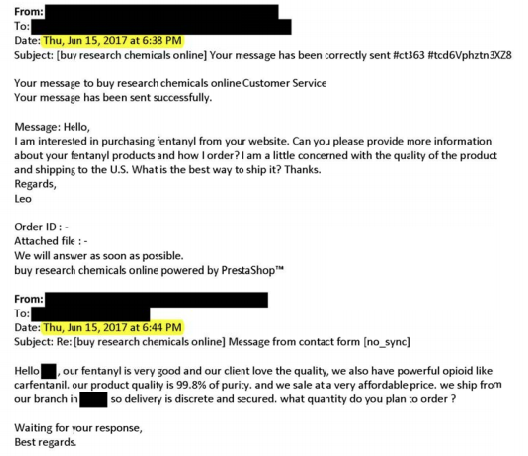

Recently, a group of investigators with the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations Googled “buy fentanyl online” on the open internet, then homed in on the six sites that were most responsive to their requests. An investigator on the committee, who was not authorized to speak publicly about the findings, said these represent a tiny fraction of the hundreds of fentanyl-selling sites on the web.

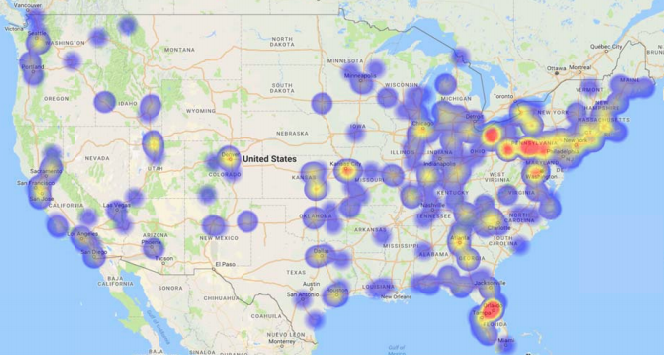

The subcommittee identified more than 500 sales, totaling $230,000, that involved the six online sellers. The greatest number of purchases came from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida.

The subcommittee also identified seven people who died from fentanyl overdoses after sending money and receiving packages from one of the six online sellers, and it found 18 people who were arrested for drug-related offenses after making purchases through them. Here’s how it describes one of these deaths in its report:

One such individual was a 49-year-old Ohioan who sent roughly $2,500 to an online seller over the course of 10 months—from May 2016 to February 2017. Over that time period, he received 15 packages through the Postal Service on dates that closely corresponded to payments he made to an online seller. He died in early 2017 from “acute fentanyl intoxication.” He had received a package from an online seller just 30 days before his death.

According to the report, most of this fentanyl originates in China. China has cracked down on fentanyl and some of its subtypes, or analogues, but the online dealers often tweak the formulas of their drugs slightly to stay ahead of bans. For example, when China announced it would ban one fentanyl product, called U-47700, on July 1, one fentanyl dealer advertised a “hot sale” of the product through June. “All must go till 1 of July,” the “special offer” read, according to the report.

Jon Zibbell, a public-health analyst at RTI International, said that the sale of many different types of fentanyl can increase the risk of overdose. It’s not that the analogues themselves are more dangerous, he said, but that “they affect the body so differently, that it’s hard [for the user] to plan and stay safe.”

The drug user in Texas said he first began using opioids when a doctor prescribed him hydrocodone for a bad cough he had as a teenager. He progressed to prescription painkillers, and then, when they became too expensive, to heroin. The heroin left him broke and with abscesses on his skin.

“It’s stronger than your willpower,” he said of the drug’s pull.

He decided to seek out something that would be both safer and cheaper. For the past three years, he’s been buying fentanyl and its analogues, like carfentanil, online. When he receives it, he measures it out in water, which he says makes for greater accuracy. He says he’s never overdosed. A day’s supply of heroin used to cost him $100. Now, for that amount, he can get enough fentanyl to last more than three weeks.

To buy his fentanyl, the man uses “darknet” sites, which are unlisted on search engines, rely on a special private browser for access, and don’t tie his username to his identity. About 50 such cryptomarkets are currently operating. He says most of the sites on the regular internet, which the Senate report focused on, are scams in which dealers will take money and fail to deliver. (The Senate investigators did not actually make any purchases.) Or, these so-called “clearnet” sites lead to arrests. “The feds are very on top of the clearnet markets,” he said.

Michael Gilbert, an independent researcher who has studied darknet drug markets, said that not only do individual users buy drugs on the darknet, so do dealers who go on to resell the drug in their local area. “A lot of people have used drugs that have flowed through cryptomarkets without knowing what cryptomarkets are,” he said.

The Senate subcommittee did not look closely at darknet sites, the investigator told me, because they found so much on the open web. The Senate investigator said Chinese authorities might have been lax in shutting down these websites in the past because opioid overdoses are not as big of a problem in that country as they are in the United States. But the investigator anticipates stricter enforcement to come.

Online drug dealers, the report notes, prefer the U.S. Postal Service because it searches for suspicious packages by hand, while services like FedEx and DHL use more rigorous, automated methods. The report recommends that all international packages start to include what they call “advanced electronic data”—special information on bar codes that could help flag drug-bearing packages for postal workers.

Gilbert dismissed that proposal, saying “the idea that advanced electronic data is going to help us get better at recognizing drugs is laughable.” Instead, he recommends legalizing all drugs and regulating them like alcohol and tobacco. The risk of overdose, people in his camp argue, is high because drugs are a poorly regulated product sold by unscrupulous middlemen. “Imagine if you went to the bar and you said, ‘I’ll have a drink,’” he explained, “and you didn’t know if it was beer, wine, or liquor.”

On Tuesday, Senators Claire McCaskill, Lisa Murkowski, and Dan Sullivan advocated helping the users themselves, urging the Drug Enforcement Administration to issue a new rule allowing doctors and other practitioners to prescribe addiction medicines, such as methadone, online or over the phone.

The Texas man, meanwhile, is already sensing a crackdown. Last July, he said, there were thousands of listings for fentanyl and its analogues on AlphaBay, a darknet site that was shut down by law enforcement. Now, on Dream Market, another darknet drug market, there are just 300.