Switch to the mobile version of this page.

Vermont's Independent Voice

- News

- Arts+Culture

- Home+Design

- Food

- Cannabis

- Music

- On Screen

- Events

- Jobs

- Obituaries

- Classifieds

- Personals

Browse News

Departments

-

Education

Town of Roxbury Sues Over Budget Vote…

-

This Old State

More Vermont Seniors Are Working, Due to…

-

Politics

Burlington Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s First Term Starts…

- From the Publisher: Still Mooning From the Publisher 0

- Home Is Where the Target Is: Suburban SoBu Builds a Downtown Neighborhood Real Estate 0

- State Will Build Secure Juvenile Treatment Center in Vergennes News 0

Browse Arts + Culture

View All

local resources

Browse Food + Drink

View All

Browse Cannabis

View All

-

Culture

'Cannasations' Podcaster Kris Brown Aims to 'Humanize'…

-

True 802

A Burlington Cannabis Shop Plans to Host…

-

Business

Judge Tosses Burlington Cannabiz Owner's Lawsuit

-

Health + Fitness

Vermont's Cannabis Nurse Hotline Answers Health Questions…

-

Business

Waterbury Couple Buy Rare Vermont Cannabis License

Browse Music

View All

Browse On Screen

Browse Events

View All

Quick Links

Browse Classifieds

Browse Personals

-

If you're looking for "I Spys," dating or LTRs, this is your scene.

View Profiles

Special Reports

Pubs+More

The Doctor Won’t See You Now: Patients Wait Months for Treatment at Vermont’s Biggest Hospital

Published September 1, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. | Updated December 13, 2022 at 7:21 p.m.

On a Friday in February, 27-year-old Andrew Charlestream went to the emergency room at the University of Vermont Medical Center with searing abdominal pain. A doctor diagnosed him with kidney stones, then sent him home with pain medication and instructions to follow up with a urologist in two to three days.

That Monday, Charlestream, who lives in South Burlington, called the urology clinic at the medical center. The person who answered the phone told him the schedulers were busy but that someone would be in touch soon. He waited, but the call never came. So he started phoning the clinic every day, repeatedly, only to be told the same thing: Someone would be in touch to schedule his visit. By the end of the week, he still didn't have an appointment.

"I'm sitting here, puking every night because I'm in so much pain, missing work, spending the majority of my days on the phone to get to talk to someone," he said.

Two weeks after Charlestream's emergency room visit, he said, the pain had become unbearable, and he went back to the emergency room for more medication. Finally, after one month and more than $2,000 out of pocket, he called the medical center's Office of Patient and Family Advocacy, and a caseworker helped him get an appointment with a urologist that week.

As it turned out, Charlestream needed surgery to remove the kidney stones. He's convinced he would have been spared a considerable amount of agony, and money, if the urology clinic had seen him promptly, as the ER doctor had ordered. "It's hard to find words other than 'utter frustration,'" he said.

Wait times for specialty care — neurology, urology, gastroenterology and other branches of medicine — have long been a problem at the UVM Medical Center, the hub of the sprawling UVM Health Network, which now includes six hospitals in Vermont and northeastern New York.

Eighteen months into the pandemic, the situation has reached a crisis point. Now, patients sometimes wait up to a year to see specialists.

Seven Days asked UVM Medical Center for the average number of days new patients wait to be seen in each of its 85 specialties. The hospital refused to provide data for all but two areas: urology, which is now scheduling two months out; and ear, nose and throat, where the current delay ranges from 20 days to see a pediatric specialist to 175 days for an ear specialist. In public filings to state regulators, the medical center reported wait times using a different metric — the percentage of new patients seen within two weeks of scheduling an appointment — which fails to capture the most egregious scenarios or offer any sense of the typical, nonurgent patient experience. Nor does it account for the weeks and months some people, such as Charlestream, must wait before they can even schedule an appointment.

Hospital leaders admit that serious problems exist, and patients shared with Seven Days the frustrating and sometimes devastating consequences of those delays. Twenty-nine-year-old Ashley Moore, who lives in East Calais, was referred to a neurologist in January for her chronic migraines and learned five months later that the earliest available appointment would be a Zoom consultation — in January 2022. A UVM Medical Center employee, who requested anonymity because of her job, found out in February that she would need to wait seven months before a gastroenterologist could see her for a severe digestive problem that had already forced her to miss weeks of work.

In September 2020, 79-year-old Peter Regan was referred to a UVM urologist, but two months later, he hadn't even gotten a call to schedule his appointment. He instead went to a urologist at Northwestern Medical Center in St. Albans, which isn't affiliated with the UVM Health Network, where he was diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer.

"I'm not a complainer," said Regan, who lives in Shelburne and worked for 45 years in the marketing department of Hazelett in Colchester. "But where I come from, you respond to the customer. This just wasn't right."

These lengthy waits, according to health care experts and medical center staff, are the result of an overburdened system. Staffing levels throughout the medical center, from the support specialists who field calls from patients to the physicians who treat them, have not kept pace with the UVM Health Network's growing pool of patients, which has expanded to roughly 1 million over the last 10 years.

When something goes awry in one part of the system, the effects ripple outward: Delays in getting MRI and CAT scans often prolong the wait to see a specialist, since some doctors require imaging before they will schedule a consultation. Meanwhile, those patients become sicker and ultimately need more intensive treatment, which also pushes exhausted health care workers to the brink.

UVM has not been alone in its subpar performance. Between 2014 and 2017, the lag between a referral — when a primary care provider directs a patient to a specialist for further treatment — and an appointment rose by 30 percent in 15 U.S. metro areas, according to a study by the health care recruiting and consulting firm Merritt Hawkins. UVM Medical Center leaders have historically blamed a nationwide physician shortage, which has become increasingly acute: A recent report from the Association of American Medical Colleges projects that the U.S. will face a shortfall of up to 139,000 physicians by 2033. To meet current patient demand, the UVM Health Network says it is seeking to hire 75 more physicians, including 57 specialists for the Burlington hospital.

But critics inside and outside the UVM Medical Center say these external forces are only part of the picture. Staff point to the chicken-and-egg blight of low morale and high turnover at every level of the institution; others question whether the hospital network has become too vast and unwieldy to be efficient. Of the two dozen patients Seven Days interviewed for this story, nearly all who finally managed to see a specialist at UVM Medical Center said they received excellent care. The problem, they said, was getting an appointment in the first place.

"We know we have challenges right now, and we're doing everything in our power to improve," said Dr. Stephen Leffler, who has been the medical center's president and chief operating officer since 2019. "It's not where we want it to be, and it's not what our patients want and need right now."

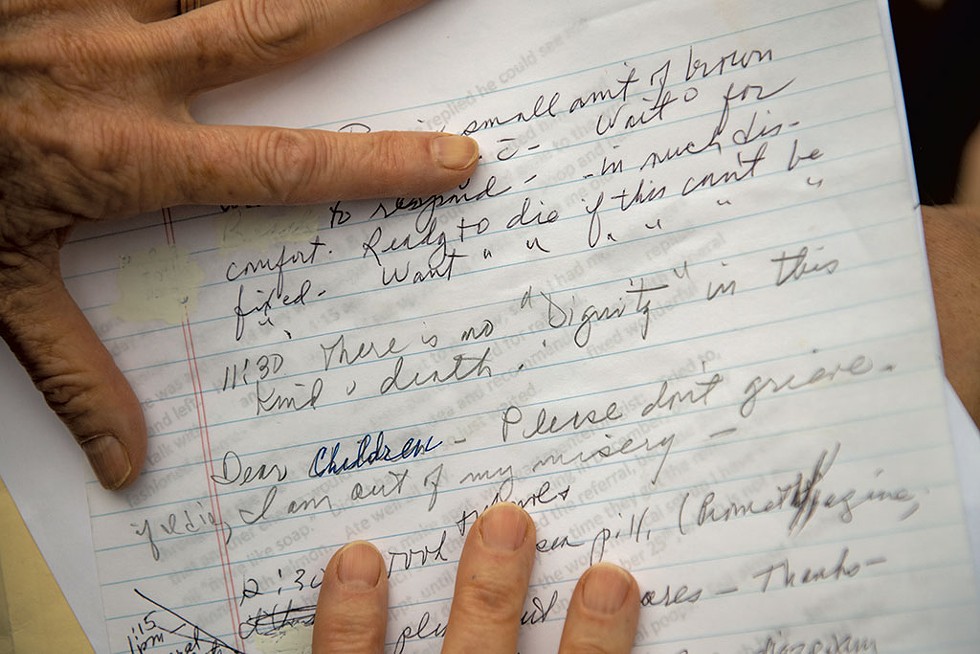

For people in acute distress, months of waiting can be insurmountable. Last summer, a 90-year-old woman suffering from incontinence caused by an impacted bowel learned that she wouldn't be able to see a UVM proctologist for almost three months. Her daughter, who requested anonymity to protect her mother's privacy, said that her mother kept a meticulous record of her interactions with her health care providers.

One of her typed notes, dated August 26, 2020, reads: "I tried to make appt with gastroenterologist ... they were booking in December, but they wouldn't give me an appt until they received the referral ... They did say that by the time they got the referral, they will be booking for February. This is the worst medical setup I have ever heard of!"

She got an appointment in late November. But her life was already a misery, her daughter said, and she decided that she was done waiting. On September 2, 2020, the woman killed herself.

Too Big to Fail

click to enlarge

- Daria Bishop

- A daughter showing notes from her mother, who died last year while waiting to see a specialist at the University of Vermont Medical Center

The UVM Health Network casts a large shadow. Launched in 2011 as a partnership between the UVM Medical Center in Burlington, then known as Fletcher Allen Health Care, and Central Vermont Medical Center in Berlin, the network has grown rapidly over the last decade, acquiring four more hospitals — three in New York and one in Vermont — and nine primary and specialty care practices. Of the roughly 1,850 specialists in Vermont, 1,055 are either affiliated with or employed by the UVM Medical Center, according to the state Department of Health's most recent physician census.

UVM Health Network leaders have maintained that consolidation has improved access to specialty care statewide by keeping the lights on at smaller regional hospitals, which handle routine care, and by creating a direct pipeline to the UVM Medical Center, where, said Leffler, physicians can concentrate on the most complex cases.

But that strategy has occasionally led to conflict. Shortly before the network acquired Porter Medical Center in Middlebury, in 2017, former Porter CEO Jim Daily had a tense exchange with John Brumsted, president and CEO of the UVM Health Network. Porter was sharing a urologist with UVM but wanted the physician to work full time in Middlebury.

"Brumsted basically screamed at me, 'Why would Porter need to employ specialty physicians?'" said Daily. "We employed specialists because we thought it served our patient population. [UVM] thought we should concentrate on primary care." To this day, Porter still shares a urologist with UVM Medical Center.

Brumsted recalls the conversation differently. "First and foremost, I'm not a screamer," he said calmly. Secondly, he continued, the urologist, along with several other specialists, wanted to split their time between Porter and UVM Medical Center. "They really wanted to be able to take their patients to a higher level of care at the academic medical center," explained Brumsted, who started his own career as a town doctor in rural New York State. There, he said, he came to appreciate the value of an integrated medical system. "I was spending a lot of my time trying to figure out how these people would get access to services in Buffalo, and in Erie, Pa.," he said. "And a lot of times, nobody was really listening."

With only a small number of specialists left in northern Vermont who don't work under the aegis of the UVM Health Network, both independent and UVM-affiliated health care providers often have little choice but to refer their patients to the medical center's specialty clinics. But some independent primary care doctors believe that UVM unfairly gives priority to patients and physicians within its network, leaving those outside it on the back burner.

Tina D'Amato, an osteopath at Evergreen Family Health in Williston, has several patients who were formerly treated by UVM-affiliated doctors, which means she has access to their referral history. "I see things that would have been dismissed as bogus if I were the referring provider," she said. In her view, referrals for issues of marginal concern — a slightly abnormal test, for instance — are much more likely to be taken seriously by the specialty clinics when they come from physicians inside the UVM Health Network.

As wait times have lengthened in recent months, D'Amato said, moving even a potentially life-threatening case to the front of the line has become all but impossible. In February, she referred a patient who she suspected had Parkinson's disease to UVM Medical Center's neurology clinic. The earliest appointment she could get for him was in November, nine months out. When her patient called the clinic to ask whether he could be seen sooner, D'Amato said, he was told that "confirming Parkinson's is not an emergency."

Each hospital clinic triages incoming referrals, according to one former patient support specialist in the urology clinic, who requested anonymity because she still works in health care in Vermont. Routine but debilitating complaints — frequent urinary tract infections, chronic abdominal pain — get relegated to a slush pile. "The only way you're going to get seen is if you're a squeaky wheel, or you go to patient advocacy, or you know someone, like the doctor, personally," she said. When she quit this summer, she said, there were some 900 unscheduled referrals for urology appointments.

But leveraging connections doesn't always work, either. One ear, nose and throat patient, who requested anonymity because she's friends with several UVM Medical Center physicians, began experiencing weeklong episodes of vertigo, vomiting and tinnitus in the winter of 2017. She couldn't eat, sleep or work; in one month, she lost 10 pounds. "I felt like death," she said. "I'd spend the night with my arms around the toilet, or else I'd throw up on myself."

Her UVM-affiliated doctor referred her to a specialist at the medical center, but she couldn't get an appointment for 10 months, even after her contacts at the medical center had intervened on her behalf. Instead of waiting, she found an independent ear, nose and throat doctor in St. Johnsbury, who saw her within two weeks and diagnosed her with Ménière's disease, a chronic but non-life-threatening condition. The disease has no pharmaceutical cure, but getting the diagnosis allayed her fears that she might be facing a potentially deadly illness.

"I have resources. I'm older. I kind of know how to game the system," said the patient. "I worry about people that can't do that."

Lately, D'Amato, the Williston osteopath, has been referring most of her patients to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, in Lebanon, N.H., where some specialties have shorter wait times. But driving an hour and 45 minutes for medical care is far from ideal. "Most people don't want to or just can't drive more than half an hour away," D'Amato said. "It's a horrible situation to find yourself in, as a patient, when the hospital closest to you can't take you for almost a year."

Dartmouth-Hitchcock wouldn't provide data on average wait times to see its specialists. In a statement, the hospital's chief quality and value officer, Carol L. Barsky, said she "can't speak to the specific challenges our colleagues at UVM Medical Center are facing" but that "wait times are not an issue specific to any one institution."

For some Vermonters, telehealth has eliminated the inconvenience of traveling out of state, making it easier for them to leave the UVM bubble. Just before the pandemic struck, Nan Kolok, who lives in Essex, wanted to see a neurologist at the UVM Medical Center for her worsening migraines, but her UVM-affiliated primary care doctor told her she would have to wait six to eight months for an appointment.

"I was like, 'My God, I can't miss any more work,'" said Kolok, who was then a counselor at the state Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living. She knew people who had better luck getting into Dartmouth-Hitchcock, so she asked her doctor to refer her there instead. In two months, she had a telehealth visit with a specialist. Since then, she's had Zoom consultations with him every three to six months, an arrangement she finds perfectly serviceable. "I don't feel the need to go back to the medical center and find a neurologist," she said.

Other patients have tried, unsuccessfully, to pry themselves loose from the bureaucracy of the medical center and go to another hospital. Before he managed to get an appointment with a urologist at UVM, Charlestream, of the kidney stone ordeal, called the medical center's emergency department and demanded to have his records sent to Gifford Medical Center, in Randolph, where he had already secured an appointment. But a staff member denied his request, Charlestream said, citing a policy of not releasing records to physicians outside the UVM Health Network. The staff member told him he could instead request a copy of his file from the hospital's records department but that the process would take weeks.

When asked about this incident, Leffler suggested that there was a "miscommunication" between Charlestream and the emergency department. "We send and receive records from hospitals to hospitals every single day in huge amounts," he said.

The exchange with the emergency department staffer happened over the phone, Charlestream said, so he couldn't provide written corroboration. But he was adamant that he hadn't misunderstood the message. "I was told explicitly that they do not give out medical records to providers outside of their network," he said.

Charlestream, who has since recovered from his surgery, is now paying off his two emergency room visits. What rankles him most, he said, was the hospital's unaccommodating posture. "If they were up-front and said, 'We can't get you in for a while; here's some pain medication' or 'Let's help you get a referral to see someone else,' I could have avoided much of it."

Some hospital networks discourage physicians from referring patients to out-of-network specialists to avoid losing revenue to competitors, even when going elsewhere might result in a faster appointment, as the Wall Street Journal reported in 2018. While Leffler insists that no firewall exists between UVM and unaffiliated medical practices, several independent specialists noted that few, if any, of their referrals come from UVM-affiliated providers. Betsy Perez, an independent urologist in Morrisville, sees a few patients each week who couldn't get into the medical center. In spite of the massive backlog there, she said, "almost none" of those patients is referred to her by UVM physicians.

Gregory McCormick, an independent ophthalmologist in South Burlington who graduated from UVM's Larner College of Medicine, said many of his patients have told him that their UVM physicians encouraged them to contact him directly. By putting the onus on the patient to make the call, he said, these physicians avoid the paper trail of an out-of-network referral, which their superiors might view as a black mark.

"I have politely learned to never send a letter to UVM that says, 'Thank you for the referral,'" he said, "because I wouldn't want someone to have it in their record."

'A Vicious Cycle'

John Little once liked his job. As a nuclear medicine technologist, he administered vital diagnostic exams and radiation treatments to shrink tumors. He enjoyed brainstorming ways to improve his department and took pride in helping patients understand the procedures they were undergoing. Most days, he went home feeling like he had made a difference.

But in recent years, he said, the UVM Medical Center's radiology department has turned into a glorified conveyor belt, leaving him no time to catch his breath, let alone consider what he could do better.

According to Little, the backlog of tests predates the pandemic, but it has ballooned over the last year and a half, even as the hospital jam-packs the exam room schedules. Radiology is now on pace to perform thousands more diagnostic tests, such as MRI and CAT scans, than the UVM Medical Center had projected for this year.

With no buffer time between exams, Little said, the schedule unravels whenever tests run long, as they tend to do when patients are claustrophobic or scared of needles. When he gets an urgent request from the emergency department, a 10-minute backup can quickly snowball into a 30-minute one. Sometimes, Little said, patients in the waiting room sense his anxiety and ask whether they can help. Others show up in a foul mood, irritated that it took so long for them to get the appointment in the first place.

This summer, Little voluntarily transferred to a research position, where he no longer works with patients. "I need to do something that doesn't make me sad," he said. "I don't like going to work feeling like I can't do a good job, because I have to treat all my patients like they're on a treadmill." One of his colleagues recently gave notice, too. With one-fifth of its nuclear medicine technologists gone, the hospital had to close one of its exam rooms. It has yet to reopen.

The last 18 months have been particularly punishing for health care workers, and frontline staff at the UVM Medical Center say they feel besieged. Last year, the pandemic forced scores of patients to postpone nonurgent care, and a cyberattack that crippled the health network's electronic records system caused even more delays.

In departments that lack adequate staff to meet demand for their services, the remaining workers have to pick up the slack. The mounting workload, and the stress of believing that they are not providing the best possible care, has taken a toll on their mental health.

"It's this vicious cycle," said Sarah Girome, an outpatient neurosurgery nurse. "We can't see people in a reasonable amount of time in a large number of specialty clinics, so more and more people are leaving because of that moral injury. People don't want to be put in that position." As Little put it, "Morale has never been lower."

Girome often tells patients with brain tumors or a suspected brain bleed that it will be at least two months before they can schedule an MRI, and she sometimes advises them to go to the emergency room, where they might have a better chance of getting on-the-spot diagnostic imaging. She acknowledged that doing so could take a bed away from someone who needs it more; with the ER suffering from its own staffing shortage, patients wait hours to be admitted, she said. But in her mind, the alternative — waiting for months — is just as dangerous.

"There are days that I go home and I cry," she said, "because I have to tell a patient, 'I'm really sorry that this is happening to you, and I know that you're terrified and scared and want and need answers, but we're just not in a position where we can give those answers to you in a timely manner.'"

"A lot of us feel very helpless," she added.

This malaise has been brewing for years. In 2018, a bitter dispute between nurses and the hospital administration over wages and staffing levels culminated in a two-day strike before the parties reached an agreement. That contract, which expires this year, raised base salaries an average of 16 percent, far higher than the hospital was initially willing to go. But the labor situation at the hospital has continued to deteriorate over the past three years, often in public view.

Last week, some 50 UVM Medical Center nurses, radiology technicians and supporters gathered in front of the hospital to demand that administrators raise wages and hire more permanent workers. To convey the scale of the staffing crunch, the demonstrators planted more than 240 plastic pinwheels in the grass, one for each union job vacancy, said Deb Snell, president of the Vermont Federation of Nurses & Health Professionals. "These are the worst staffing levels I have ever seen," said the 22-year nurse, who works in the intensive care unit.

During the pandemic, the UVM Medical Center has scrambled to staff its floors by offering overtime shifts to anyone who will take them and by enlisting a costly battalion of travel nurses. These nurses, who typically come from outside Vermont, work on short-term contracts that pay up to four times more than permanent staff wages, further fueling the ire of unionized nurses. The hospital's payroll now includes the equivalent of more than 160 full-time traveling nurses and doctors, budget documents show, 40 more than two years ago. The hospital expects to spend $40 million on temporary workers this fiscal year.

Leffler said the hospital aims to hire 180 nurses to reduce its reliance on travelers. But the public demonstrations of discontent, combined with the rancorous atmosphere within the hospital, would seem to undermine his recruitment efforts. A recent survey of nurses and technicians by the nurses' union found that 85 percent of the 800 respondents had experienced "moral distress," the feeling of being stretched too thin to provide adequate care. More than half of all respondents said they would not recommend their unit to a colleague, and three of every four nurses reported that they had thought about leaving the hospital within the last year.

These personnel challenges extend beyond medical staff. Entry-level jobs have the highest turnover rate of any positions at the medical center, accounting for nearly 50 percent of the hospital's current vacancies. New, inexperienced staff inevitably make more mistakes, triggering a domino effect that can exacerbate the wait-time problem. Doctors sometimes request prompt follow-ups with patients, only to find out later that the appointments never got scheduled, according to one UVM neurologist who requested anonymity. "Suddenly, you're aware of this problem at the time you're supposed to see that patient," the doctor said, "and feel an obligation to squeeze them in on top of everyone else."

The longer people wait for care, the more likely they are to become critically ill. The neurology nurse said she often encounters people who have been admitted to the hospital as a result of a condition for which they were waiting to see a specialist. A patient who suffers from debilitating migraines, she said, might have an episode while driving and crash.

"If they're going to be seen outpatient, they're going to go about their daily lives," she said. "They can't necessarily stop working, so people will continue to do what they do until there's an accident. That's happening again and again."

Coming Up Short

click to enlarge

- Colin Flanders ©️ Seven Days

- Deb Snell, president of the Vermont Federation of Nurses and Health Professionals, speaking during a union press conference last month

Midway through a seven-hour Zoom budget hearing on August 25, as the nurses stood with their pinwheels on the hospital lawn, UVM Health Network leaders fielded questions about its current wait-time data from the Green Mountain Care Board, the five-member regulatory body that oversees Vermont's health care system.

The medical center's goal is to see at least 80 percent of new patients within two weeks, said a UVM Health Network spokesperson. But according to the latest findings, 78 of the hospital's 85 specialty areas failed to meet that standard. Some clinics, such as gastroenterology and rheumatology, didn't succeed even 35 percent of the time.

"We have a significant access challenge right now," Leffler told the board, "as great as any challenge I've seen as long as I've been here."

When asked about reports of low staff morale, Leffler appeared to get misty-eyed as he talked about how the pandemic has impacted his staff. "It's no secret that UVM Medical Center has been through a really rough 18 months," he said. "The stress every single day of not having the staff you need for everybody here is overwhelming."

Now a decade old, the Green Mountain Care Board remains one of the most potentially powerful state health care regulators in the country; its paid members earn average salaries of $111,000 and are appointed by the governor to six-year terms. The current appointees include a Middlebury College economics professor, a BlackRock board member and several career bureaucrats; their task is to set health insurance rates, approve hospital budgets and maintain Vermont's health care claims database. They also influence access to care by issuing "certificates of need," which hospitals and other health care providers must obtain before acquiring new diagnostic equipment, for instance, or building a new hospital wing.

In theory, certificates of need keep health care costs down by preventing unnecessary duplication of services. But some critics argue that the bureaucracy-laden process favors large, well-established health care organizations at the expense of smaller ones, limiting patients' options.

A case in point is the multiyear controversy surrounding the Green Mountain Surgery Center in Colchester, which offers independent physicians an alternative to UVM's facilities to perform outpatient procedures. The project faced sustained opposition from the UVM Medical Center and from the state's hospital association, which argued that the surgery center would siphon patients away from small, financially ailing hospitals. The Green Mountain Care Board finally approved the project in 2017.

Four years after arguing against the creation of a new surgery center, the UVM Health Network is proposing one of its own to replace the since-shuttered operating and procedure rooms at Fanny Allen, which closed last year after a mysterious odor began sickening employees. It is also seeking approval for a $4 million expansion of its orthopedic center and a new MRI machine to help alleviate the imaging bottleneck.

The board's mandate would seem to include tackling the wait-time problem, which presents an impediment to getting health care, but it has historically taken a hands-off approach to the matter. The August 25 budget hearing was no exception. Aside from a few probing questions about the hospital's struggles to meet patient demand, the tone of the inquisition was mostly sympathetic. "I know you're making efforts," said board member Jessica Holmes, the Middlebury economics professor, not long after stating that she herself has tried to schedule appointments at the medical center but was "so discouraged" by the wait times that she sought care elsewhere. "I also hear the frustration in your voice, because I know, Dr. Leffler, this is not something you want."

In an interview last month, Green Mountain Care Board chair Kevin Mullin, a former Republican state legislator, said he had only recently asked the board's staff attorney to investigate its authority to compel improvement. He said he dislikes the carrot approach of offering financial incentives to reduce wait times: "I don't think you pay somebody for doing the right thing."

History suggests that the stick might not work, either. Threats to limit budget increases for failing to meet specific standards would likely elicit a barrage of doomsday predictions from network leaders. Last year, when the board approved a lower budget increase than the UVM Medical Center had requested, health network CEO Brumsted responded by suggesting that the hospital would ultimately have to eliminate some specialized services.

"As a result of those terribly difficult and avoidable decisions, Vermonters will need to travel many hours for care they currently receive close to home, and Vermont's health care dollars will flow to out-of-state hospitals that provide more expensive care," Brumsted wrote in a missive to the board, making no mention of the fact that this trend is already in motion. "The consequence of your decisions will undoubtedly impede access and make care less affordable in this state."

Even without regulatory pressure to reduce wait times, the UVM Health Network would seem to have a clear financial and moral incentive to do better. As Brumsted noted, every patient who seeks care outside the network represents lost revenue; doctors who feel overwhelmed and overworked will look for new jobs; the problem metastasizes.

The health network's leadership has marshaled its existing resources to chip away at the stack of unscheduled appointments: In 2019, the network enlisted 50 employees to scour the schedules for last-minute openings in endocrinology, gastroenterology and urology. The program, known as the Patient Access and Service Center, has been a modest success, reducing the backlog for colonoscopies by 40 percent — from 6,256 to 3,966 — and helping some 150 people get earlier appointments at Central Vermont Medical Center's urology clinic, according to Scott O'Neil, the center's director.

"Over the last 12 months, we have scheduled about 9,000 appointments that otherwise would likely not have been scheduled," he said, adding that the network hopes to hire about 25 more people at the center in the coming year to increase its capacity.

But finding efficiencies in the scheduling process is only part of the solution. The bigger challenge, according to Leffler, is recruiting more specialists. Over the past two months, the medical center managed to hire four of the 10 neurologists Leffler says will be necessary to meet demand; in radiology, Leffler hopes to hire eight more doctors.

In his view, UVM would be a better suitor if it had "current and modern" facilities with state-of-the-art equipment, such as the proposed MRI machine and surgery center. "In the past, we relied on how great Vermont is, and that worked for us for a long time," said Leffler. "The marketplace is much more national now."

Employees such as Little, the former nuclear medicine technologist, are tired of the administration's hand-wringing over the state of the job market. "You guys are the ones that are in charge," he said, exasperated. "I don't go to my patient and say, 'There's some problem across the nation, so I can't help you.' I deal with what's in front of me right here."

Daily, the former CEO of Porter Medical Center, agrees the UVM Health Network administration can't keep falling back on its rhetoric about workforce issues.

"We can't have UVM controlling the portion of the market it controls with 11-month wait times for patients," he said. "There's a part of me that has respect for Brumsted and Leffler. But if you're going to assume this mantle of responsibility, you've got to do better."

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor

and we'll publish your feedback in print!

About The Authors

Chelsea Edgar

Bio:

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Chelsea Edgar is a staff writer for Seven Days, and has written for BuzzFeed and Philadelphia magazine.

Colin Flanders

Bio:

Colin Flanders is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse. He previously worked as a reporter at a group of Chittenden County weekly newspapers covering Essex, Milton and Colchester.

Colin Flanders is a political reporter at Seven Days, covering the Statehouse. He previously worked as a reporter at a group of Chittenden County weekly newspapers covering Essex, Milton and Colchester.

Latest in Health Care

Related Locations

-

University of Vermont Medical Center

- 111 Colchester Ave., Burlington Burlington VT 05401

- 44.47966;-73.19404

-

Be the first to review this location!

Related Stories

Speaking of...

-

UnitedHealthcare Reaches Last-Minute Deal with UVM Health Network

Feb 21, 2024 -

Ukrainian Man Pleads Guilty to UVM Medical Center Cyberattack

Feb 19, 2024 -

A New UVM Medical Center Effort Seeks to Support Dementia Caregivers

Feb 7, 2024 -

Vermont Health Care Workers Are Grappling With Unprecedented Workplace Violence

Nov 15, 2023 -

Board ‘Taken Aback’ by Chief Murad’s Behavior at Hospital, but Clears Him of Misconduct

Oct 25, 2023 - More »

find, follow, fan us: