As Winter Olympics end, will China’s hosting win medals for diplomacy?

- Negotiating controversies and Covid-19, the Games offered a window to a world much changed from 2008, when Beijing staged the summer edition

- Foreign leaders were received in person after the relatively isolated two years of the pandemic, but benefits to China’s image may take longer to assess

Although China was not expected to rival the leading traditional winter sports countries in total number of medals won, it was eyeing a diplomatic win from an occasion that has always been about more than sport.

The narrative of having achieved a great Olympics was already backed by the International Olympic Committee’s announcement on Saturday that the symbolic Olympic Cup award for the event would go to Chinese people for their “warmth, energy, hospitality and support”.

“Beijing 2022 could not have achieved this level of excellence without the support of the Chinese people,” IOC president Thomas Bach said.

At the root of international scrutiny of Beijing 2022 was scepticism over China’s suitability to stage a global event at a time when it stands increasingly at odds with the West.

The Olympics also represented the first high-level diplomatic event held in China in over two years, because its borders had been largely closed to foreigners since Covid-19 emerged in December 2019 in central China. That has essentially cut off in-person diplomacy, making any diplomatic presence at the Games an opportunity to replenish goodwill.

During the pre-Games controversies, China had asked repeatedly that the world refrain from “politicising” the event. And as Beijing 2022 officially opened on February 4, sport began to at least partially obscure the criticism.

As for the potential pitfalls of Covid-19 and disputes about free speech, there has so far been little suggestion of the Games becoming a superspreader event, and there were reports of Chinese authorities asking athletes to take down social media posts about flooded hotels, but these were quickly denied by the nations in question.

Athletes appeared to largely heed calls by the IOC to keep politics out of their visit to China, waiting until they had returned home to make statements about Beijing’s alleged human rights abuses.

Susan Brownell, a professor of anthropology with a focus on China and Olympics at the University of Missouri-St Louis, said that verdicts on whether China’s national image had been enhanced would be mixed.

“[Hosting] will reinforce the beliefs held by China critics, but some people could be persuaded to see China in a more positive light,” she said.

Previously a nationally ranked athlete in the US, Brownwell represented Beijing in the 1986 Chinese National College Games during her Chinese language studies, setting a national record in the heptathlon.

Brownwell said it was likely that some would see the disciplined, organised manner of China’s hosting as stemming from authoritarianism, but that it had shown it could “control Covid and organise a wonderful sports event”.

“This was a way of repairing the damage done to China’s image by the fact that the pandemic started here,” she said.

“Russia has emerged as the bad guy, because of the perceived threat to Ukraine and the doping scandal in figure skating,” she said. “This makes China look like a good global citizen by contrast – despite its perceived threat to Taiwan, it does not appear to be preparing to invade its neighbours, and has not had any doping scandals, while organising a big party under difficult conditions.”

Receiving about 30 heads of state during the Olympics may also have strengthened some personal relationships, Brownwell added.

Despite claims from the Chinese foreign ministry that “no one actually cares” if nations’ politicians and officials boycotted, Beijing was understood to be significantly ramping up diplomatic efforts to invite foreign heads of state and members of royal families to attend the opening ceremony.

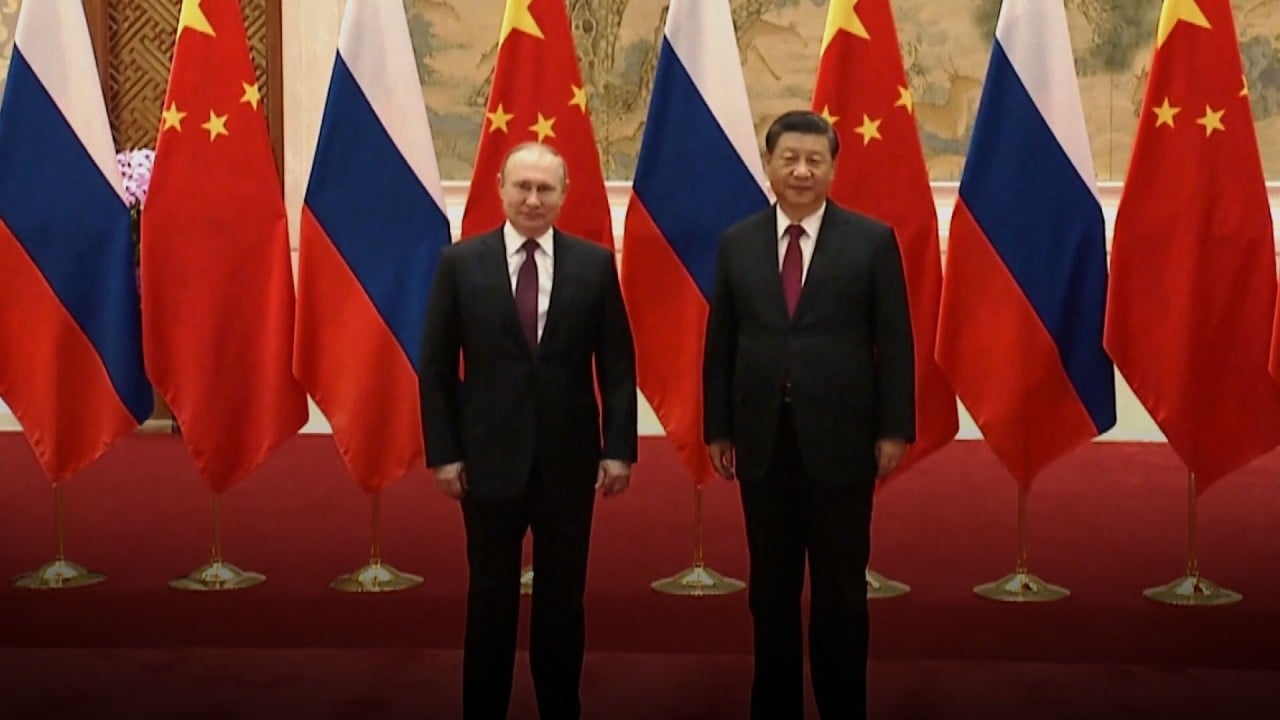

Once the big night came around, China made use of the occasion to celebrate its united front with Russia, which shares its position of being under pressure from the West, in particular the United States.

Putin was also the first leader to meet Xi, ahead of counterparts from countries including Pakistan, Argentina, the five Central Asian countries and Poland – the only European Union country to send an elected leader.

Heather Dichter, an expert on the Olympics at De Montfort University in Britain, said the diplomatic achievement was rather limited.

“China may have moved a little bit closer to Russia, or shown the world the bond between the two through Putin’s presence at the ceremony, but on the whole, the Olympics did not bring China diplomatic or geopolitical gains,” Dichter said.

“The focus on other issues such as human rights and the lack of press freedom became more widely known across the world, instead of the Games increasing global affinity for China.”

Beijing has highlighted its distinction of becoming the first city to have staged both Summer and Winter Olympics, but Dichter said this was left looking a little hollow by the lack of real snow and images being beamed around the world of industrial chimneys looming over the skiing venue.

More than 350 snow machines were used to prepare the conditions for the Winter Olympians, making Beijing the first host to use 100 per cent artificial snow. There has been criticism about the 49 million gallons of water required to generate it, after the emphasis Beijing placed on its commitment to organising a green Games.

There was scrutiny of China over human rights then, too, regarding Tibet on that occasion.

Huang Renwei, former vice-president of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, said China’s efforts to stage the event smoothly were proving people wrong even if they chose to focus on human rights.

“It would also be unfair to compare directly how much China gained from organising the Olympics in 2008, because that was the first time, so of course it seemed more impressive,” Huang said, adding that the winter edition was always a smaller affair.

Pang Zhongying, a distinguished professor of international studies at Ocean University of China, said several topics that brought international attention had also raised questions domestically, especially the dual nationalities of Chinese athletes.

Who is Chinese-American ski prodigy Eileen Gu?

“Being a host country has always been a double-edged sword for China,” Pang said. “It was a direct way to boost nationalism and patriotism domestically, but it also brought out a lot of questions.”

And with a majority of China’s ice hockey players being white and almost half of the wider Olympic team’s coaches being foreigners, it was debatable whether nationalism was stoked as it had been in 2008, Pang said.

It was nonetheless Chinese athletes’ best Winter Olympics to date in terms of number of medals.

If completing the Games with big-name athletes competing and without coronavirus cases snowballing went a long way to meeting domestic expectations, the global legacy of the Games would take longer to assess, according to Pang.

“China’s position in the world is certainly different from when it applied to be host and also from 2008,” he said.

“In the past two years, it’s felt like China has been segregated from the world [by its Covid-19 policies]. The key to assessing the diplomatic achievements of this Olympics is whether it marks the beginning of a new stage of opening up, or the end of China’s opening up.”

The world would be waiting to see whether, after welcoming foreign guests for the Games, China would be more open to the world in future or allow a resumption of in-person meetings between officials, he added.

Pang recalled the boost to the country’s status after it projected itself as an engaging global power at the 2008 Games, with the US showing greater willingness for bilateral cooperation under incoming president Barack Obama.

“But after this year’s Games,” he said, “it is unclear what lies ahead.”