Experiencing art, whether through melody or oil paint, elicits in us a range of emotions. This speaks to the innate entanglement of art and the brain: Mirror neurons can make people feel like they are physically experiencing a painting. And listening to music can change their brain chemistry. For the past 11 years, the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience in Amsterdam has hosted the annual Art of Neuroscience Competition and explored this intersection. This year’s competition received more than 100 submissions, some created by artists inspired by neuroscience and others by neuroscientists inspired by art. The top picks explore a breadth of ideas—from the experience of losing consciousness to the importance of animal models in research—but all of them tie back to our uniquely human brain.

WINNER

Still image from the performance film Mare Incognito.

Credit: Mirjam Somers, Bas Czerwinski

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Mare Incognito

by Daniela de Paulis

In the moment between wakefulness and sleep, we may feel like we are losing ourself to the void of unconsciousness. This is the moment Daniela de Paulis explores with her interdisciplinary project Mare Incognito. “I always had a fascination for the moment of falling asleep,” she says. “Since I was a very small child, I always found this moment as quite transformative, also quite frightening in a way.” The winning Art of Neuroscience submission is the culmination of her project: a film that recorded de Paulis falling asleep among the silver, treelike antennas of the Square Kilometer Array at the Mullard Radio Observatory in Cambridge, England, while her brain activity was converted into radio waves and transmitted directly into space. “We combined the scientific interest with my poetic fascination in this idea of losing consciousness,” she says. In the clip above, Tristan Bekinschtein, a neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge, explains the massive change humans and their brain experience when they drift from consciousness into sleep. As someone falls asleep, their brain activity slows down in stages until they are fully out. Then bursts of activity light up their gray matter as their brain switches over to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and they begin to dream.

As de Paulis began to drift off, the activity in her brain streamed up into the cosmos, although she says she was too cold under the stars to dream. “Mare Incognito is essentially the unknown sea and the unknown ocean, and I feel like both the brain and the cosmos have equal amounts of the unknown,” de Paulis explains. “They are [both] the next frontier of science, of research and of human knowledge in a way.”

HONORABLE MENTION

Credit: Dawn M. Hunter

Dueling Cajals

by Dawn M Hunter

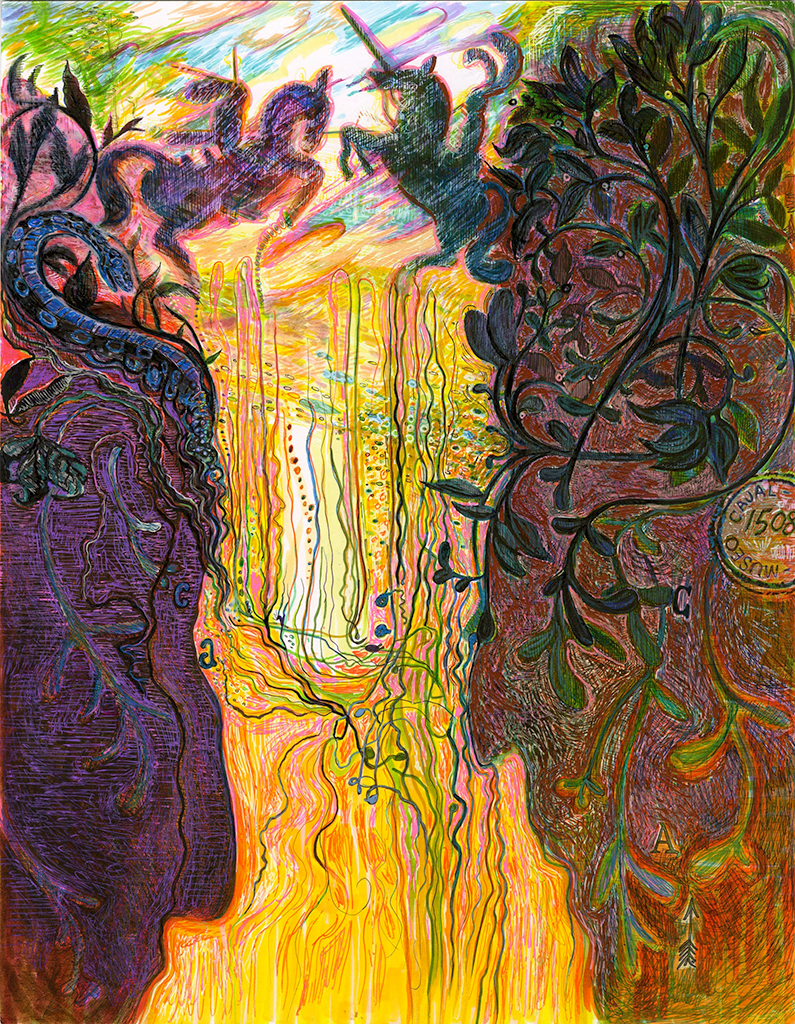

As a Fulbright Scholar, Dawn M. Hunter spent weeks viewing a collection of Santiago Ramn y Cajal’s original works, personal items and death mask at the Cajal Institute in Spain. Drawing inspiration from these items, Hunter created Dueling Cajals. Look closely at this vivid work, and you’ll see many tributes to the legacy of this Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist. Even the color palette is an ode to Cajal, inspired by the color schemes in some of his artistic works, Hunter says. The swirls and lines in the middle of the piece are inspired by Cajal’s own drawing of a nerve sliced open. Stepping back, seemingly mirrored profiles of Cajal himself emerge from dark sides of the drawing, traced from the shadow of his death mask. “You can see in the profiles,” she says, “his profile is very different on either side.” A web of plants cut through the right profile, and a snake rears from the left, both references to the cover of Cajal’s 1906 Nobel Prize–winning work on the structure of the nervous system. Dueling Don Quixotes top the piece as a tribute to Cajal’s love of the novel. All told, Hunter hopes her work gives the viewer a sense of the humor and creativity she saw in all of Cajal’s works. “He’s definitely as alive in my imagination as anybody you would meet in real life,” she says.

HONORABLE MENTION

Credit: Emma Levie

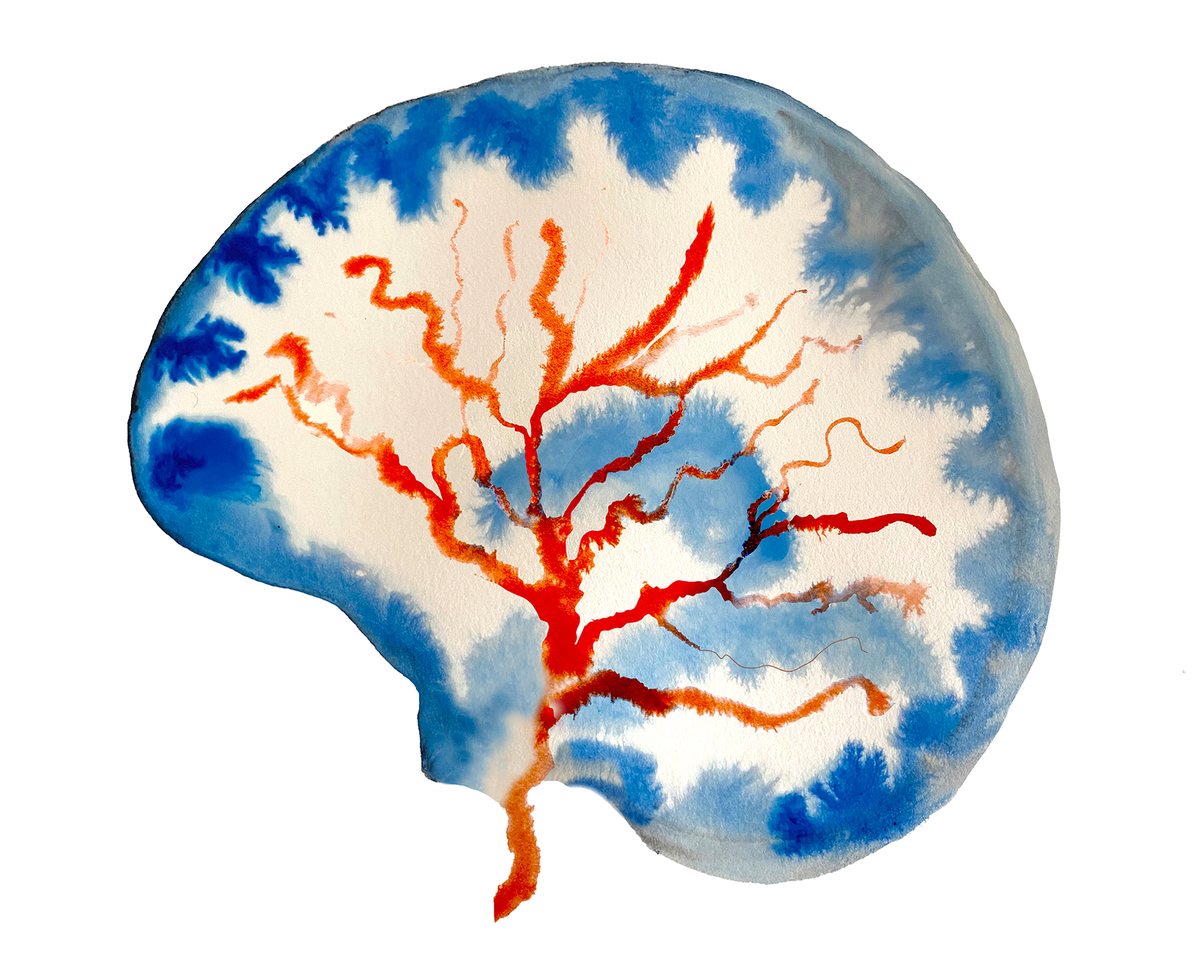

The Cerebral Fluids and Vasculature

Commissioned by Daphne Naessens

Over half of the human brain is water. “I think a lot of people don’t focus on the fluids because they think they are not so important,” says postdoctoral neurobiologist Daphne Naessens. These fluids are what she studied while working on her Ph.D. which focused on how the brain maintains fluid homeostasis and transports solutes. When Naessens graduated, she commissioned The Cerebral Fluids and Vasculature to grace the front cover of her thesis. The watercolor painting represents the liquids that she studies, Naessens explains, further highlighted by being colored blue. “The blood vessels in red are, of course, important because I studied [brain fluids in mice with] high blood pressure,” she says.

HONORABLE MENTION

Opulent

by Quirijn Verhoog

This audiovisual piece is multilayered. Quirijn Verhoog, one of the creators of Opulent, says he was inspired to make music after coming home from traveling. He wanted to explore how humans interpret beauty inspired by both nature and technology. When pandemic lockdowns started, creating music was a good way to pass the time. He made the pulsing, rhythmic music in this piece using a home-built modular synthesizer. “I wanted to express beauty, so I did go for chords that are a bit happy or sentimental,” he says. The music starts soft but builds into a crescendo of these chords, all the while accompanied by mesmerizing, AI-generated visuals.

The video was made in collaboration with Oded Welgreen, a software engineer and artist. A neural network—artificial intelligence that learns in a way reminiscent of our own brain—was trained to take shapes and turn them into images of nature. For example, Verhoog explains, a triangle becomes a mountain, uncannily synchronized to the eerie music.

HONORABLE MENTION

Credit: Anne Wienand

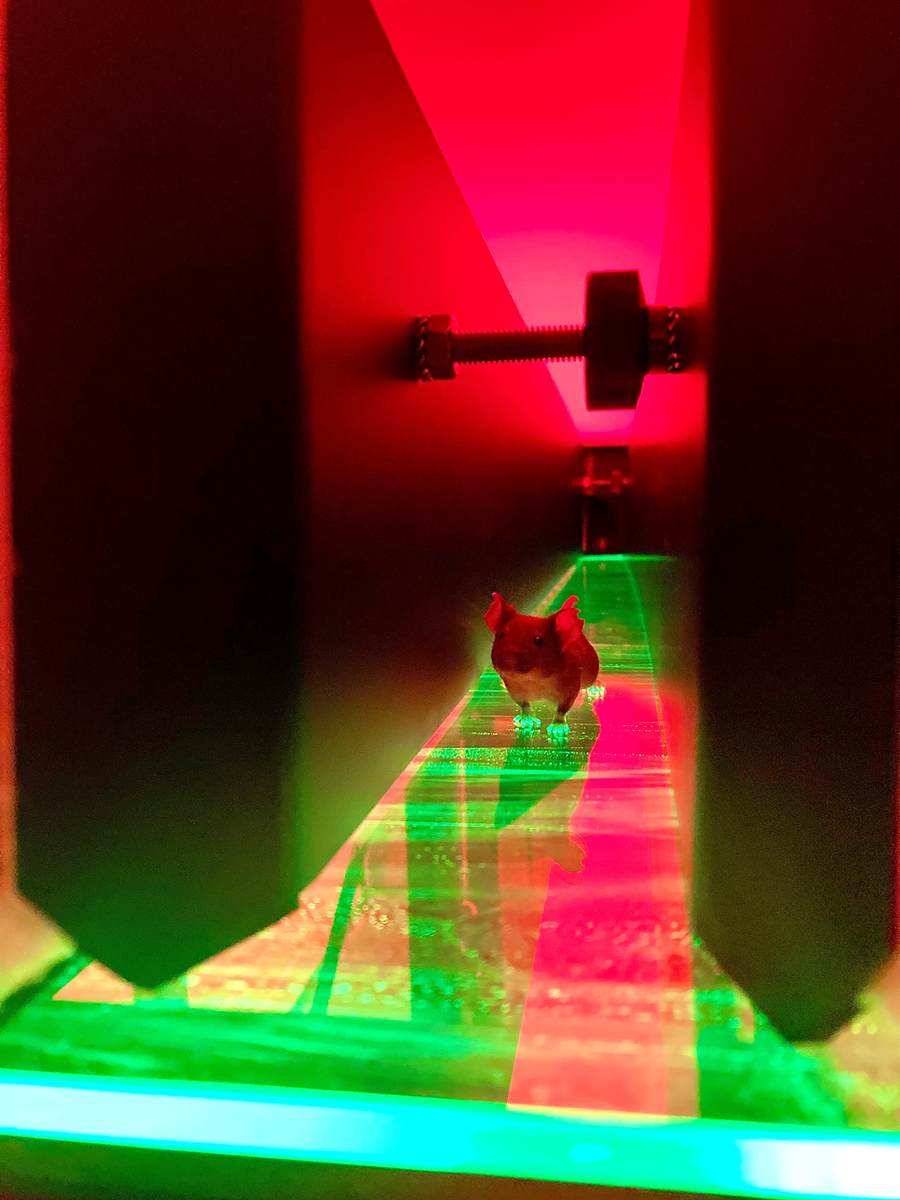

On the Path of Green: Science with a Light Footprint

by Anne Wienand

When Anne Wienand snapped this photograph, she says, it was for purely scientific purposes. The illuminated subject is a mouse that has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig’s disease. A camera underneath the green catwalk captures each of the animal’s tiny footsteps while the red background light makes its body look like a dark silhouette in the image data. Wienand uses these data to figure out how the mouse’s gait changes as its ALS progresses. The disease causes nerve cells to break down, and both mice and humans who have it get weaker and weaker over time. For this research, using mice as a model is a necessity because it enables Wienand to measure that change in gait—something that is not possible in nonanimal models such as simple cells and stem cells. “It’s important to acknowledge that, at least at the moment, it is still important to allow scientists to make use of animal models where it makes sense,” Wienand says. “And then, in parallel, it’s also important to really look for alternatives.”

EDITOR’S PICK

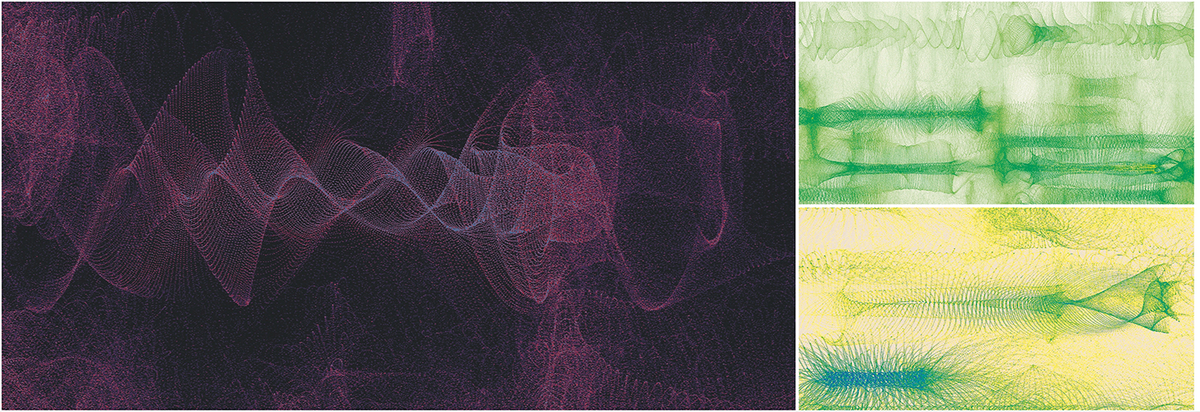

Three pieces in Simone Frettoli’s EEG WEAVER project: SOUND (left), HARMONY (top right) and FOCUS (bottom right).

Credit: Simone Frettoli

EEG WEAVER project: SOUND, HARMONY and FOCUS

by Simone Frettoli

These colorful swirls are representations of creator Simone Frettoli’s own electroencephalogram (EEG) waves. Inspired by a history of meditating, Frettoli wanted to see if the practice was observable in their brain waves. The images were generated by taking the raw EEG data and running them through computer programs to make the abstract patterns here.

EDITOR’S PICK

Credit: Sean Keating

“If You Truly Love Nature Neuroscience, You Will Find Beauty Everywhere”

by Sean Keating

In a re-creation of Vincent van Gogh’s iconic masterpiece The Starry Night, slices of brain tissue replace swirls of paint. Ph.D. student Sean Keating of the Queensland Brain Institute in Australia uses fluorescently labeled neurons, colored blue and white, to paint the sky. The structure of the hippocampus, prominently swirling, is featured in the center of the piece. The glowing gold stars are astrocytes: these cells control the permeability of the blood-brain barrier and are named for their starlike shape.

EDITOR’S PICK

Credit: Peter FitzGerald

Connemara Abstract 1c

by Peter FitzGerald

The through line of artist Peter FitzGerald’s recent work is the concept of syndesis, or binding things together. This work entwines the viewer’s level of attention with specific shapes. Concentric circles and dots are metaphorical representations of attention that become actual points of focus when the viewer’s eyes pause to take them in. Do you feel your attention moving down the arcing lines? Those red arcs represent the movement of attention. Patterns break through the viewer’s perception and change their understanding of the image, adding additional dimension. Through his use of these different shapes, each representing the reaction they cause in the brain, FitzGerald binds mental, perceptual and neural processes together into art.

EDITOR’S PICK

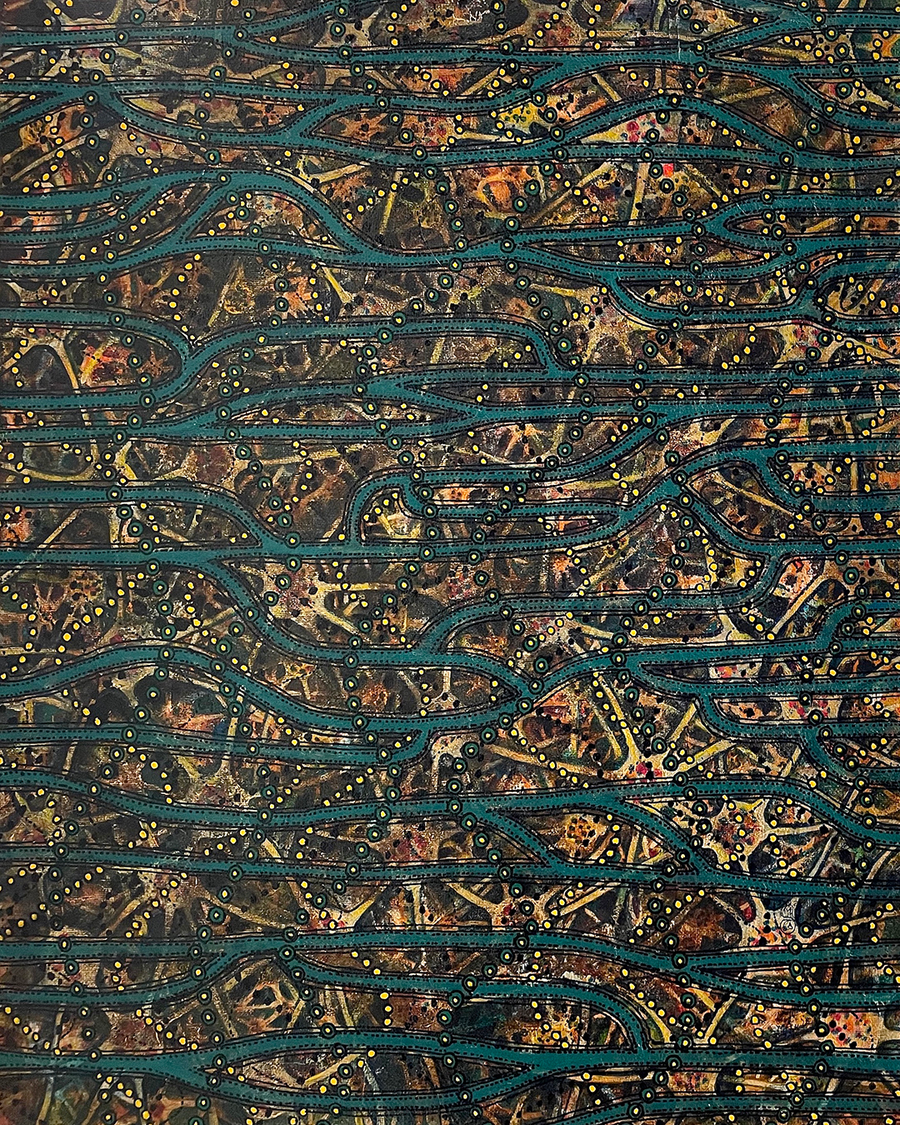

Credit: Shanthi Chandrasekar

Neurocosmology- Networks

by Shanthi Chandrasekar

Blue-green pathways race across artist Shanthi Chandrasekar’s Neurocosmology- Networks atop a background of yellowish-brown neurons. Points of pale yellow dots swirl down the image, looping over and under the blue trails. Chandrasekar creates an intricate network of shapes, patterns and colors reminiscent of the complex networks that surround us, from digital systems to our own brain.