How an alleged charter school conspiracy netted $50 million

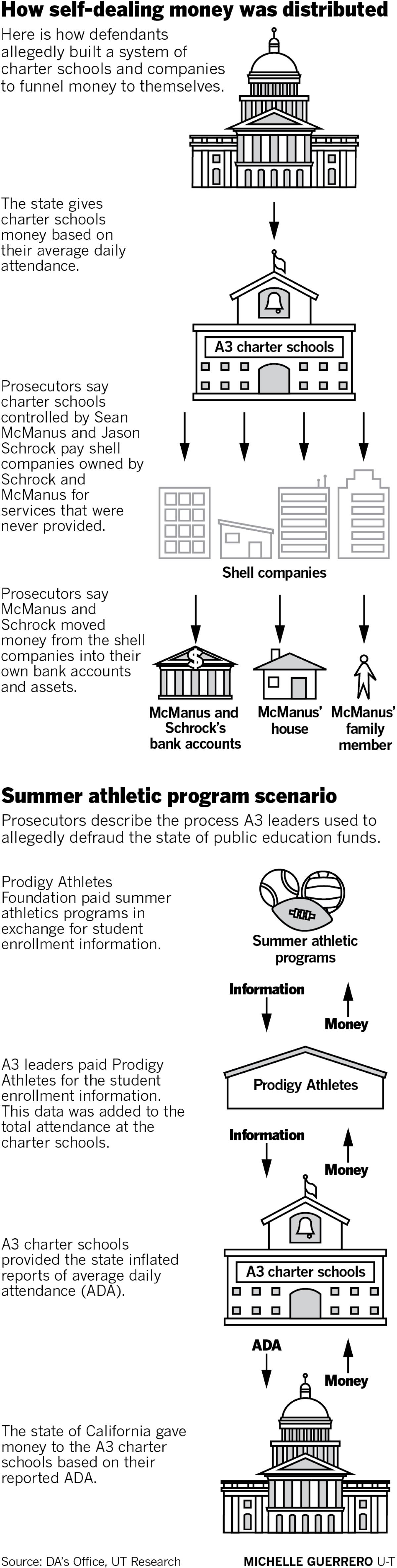

Using in-depth knowledge of California education funding, charter school regulations and deceptive business disclosures, an Australian citizen and his partner in Long Beach orchestrated a multi-year conspiracy to fleece taxpayers out of more than $50 million, prosecutors say.

Sean McManus, 46, an Australian who operated charter schools in California, and another charter school operator, Jason Schrock, 44, and nine others were named as defendants in a 67-count indictment announced this past week by the San Diego County District Attorney’s Office.

Prosecutors say McManus, Schrock and others enrolled thousands of students into online charter schools, often without their knowledge, and collected millions in state funds using student information obtained from private schools and youth athletic groups.

“This criminal enterprise funneled millions of taxpayer dollars into private bank accounts of the defendants,” said District Attorney Summer Stephan.

Eight of the 11 co-defendants have pleaded not guilty and denied the allegations. Two more are expected to be arraigned June 6.

An attorney for one of the defendants, Eli Johnson, said he wants to remind the public that an indictment does not indicate guilt. When somebody is charged with a crime, they are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

A lawyer for another defendant, Justin Schmitt, wrote in an email that his client did not intentionally engage in wrongdoing and charter school law is open to interpretation.

“Charter School Experts often cannot agree on the meaning of these regulations,” wrote Chuck LaBella. “The full facts demonstrate an absence of any intention by Mr. Schmitt to violate any law.”

Prosecutors said Schrock and McManus were the leaders of the scheme. Neither man could be reached for comment.

Schrock pleaded not guilty.

McManus is at large, possibly in Australia, prosecutors said. A San Diego Superior Court judge issued a $5-million bench warrant for his arrest and froze the accounts of charter schools, related companies and individuals related to the alleged conspiracy.

The other defendants could not be reached for comment.

County prosecutors said they worked for a year to untangle the alleged conspiracy. The 235-page indictment handed down by a grand jury describes how defendants allegedly built an intricate, statewide web of 19 online charter schools and half a dozen shell organizations; duped parents, private schools, youth sports programs and public school districts; and evaded detection by auditors and regulators long enough to pocket millions in state funds from 2016 to February 2019 — all while failing to provide services to all the students they claimed to have enrolled.

The Union-Tribune combed through hundreds of “overt acts” alleged in the indictment to understand how prosecutors say the conspiracy unfolded, including a collection of alleged scams. Here are a few.

An alleged conspiracy takes shape

In November 2016, McManus and Schrock bought the rights to manage, operate and collect public funds from two existing charter schools which were authorized in Los Angeles and San Diego counties, prosecutors said. They had help from consultant — now co-defendant — Steven Van Zant, 56, of San Diego, according to the indictment.

Van Zant in 2016 pleaded guilty to violating conflict of interest laws while brokering charter school deals.

In this case, Van Zant allegedly helped McManus and Schrock’s corporation, A3 Education, gain control over two online schools, according to prosecutors, and Van Zant pocketed 3 percent of the $1.5 million purchase price for each as well as 3 percent of state funding the schools received annually.

Van Zant’s lawyer, Sarah Shekhter, declined to comment on the indictment.

Prosecutors said the defendants set up a new corporation for each school, later changing the names to Valiant Academy L.A. and Valiant Academy of San Diego. Valiant Academy L.A. was authorized to run as an online charter school by Acton Agua Dulce Unified School District. Valiant Academy of San Diego was authorized by the Dehesa Elementary School District.

The charter schools operated under several different names between November 2016 and April 2018, the indictment said.

Prosecutors say Schrock and McManus hired Nyla Crider — now one of the co-defendants — in April 2017, to help them expand enrollment at the Valiant schools by starting a summer school program.

They told Crider she needed to obtain a “masters agreement” parents signed for the short-term study program, a birth certificate and a proof of address for each student to enroll in the summer program. In May Valiant hired Kalehua Kukahiko — now a co-defendant — as a registrar.

The indictment said Crider, Kalehua Kukahiko, and her husband, Troy Kukahiko, decided to form the Prodigy Athletes Foundation, a nonprofit that would offer the summer program and “donate” money to existing youth sports organizations — such as softball teams, a cheerleading organization and high school football teams — for each student they enrolled in the summer program.

Prodigy was not formally established until the middle of July 2017, prosecutors said, but to create the appearance of complying with state education funding rules, the defendants back-dated students’ master agreements to reflect a July 1 date.

Such backdating is against the law, prosecutors said.

Prosecutors alleged that, to get maximum state funding, Valiant told the state its summer program lasted 175 days but that the students dropped out after 40 days. In reality, Prodigy had intended to enroll students for only 40 days, according to the indictment.

Valiant eventually collected from the state $40 per student per day, for the 40 days, which amounts to $1,600 per student, the indictment said.

While payments to athletic organizations and finders fees for recruiters varied, the cost of recruiting students for Prodigy’s summer program was typically much less than what Valiant received from the state, prosecutors said.

For example, at one point, prosecutors said, the state paid Valiant $1,600 per student and Valiant paid Prodigy $500 per student and some sports organizations $200 per student, leaving Valiant’s leaders with a $900 profit.

In mid-July, 2017, Crider and Kalehua and Troy Kukahiko sought out the San Juan Hills High School football team, the indictment states. They successfully pitched the idea to the football coach, misleading him about certain details, prosecutors said.

The coach agreed to send parents emails developed with the co-defendants, telling them that enrollment in Prodigy and Valiants’ program was mandatory. The coach, who has not been charged with a crime, attached enrollment paperwork backdated to July 1 and asked parents to fill it out, according to the indictment.

Some parents expressed concern and were told that the program’s curriculum was already built into the existing sports program and would not require any extra effort or time for student athletes.

When Prodigy received the students’ enrollment documentation, it passed it to Valiant, which wrote checks to Prodigy, prosecutors said. Prodigy took a cut then paid the youth sports organization a smaller, agreed-upon amount, prosecutors said.

Paying for student’s personal information is a crime. Knowingly selling students’ information may also raise legal issues, but prosecutors said they focused on the purchasers for the charter school investigation.

Alleged self-dealing

“Conspirators, while in total control of all of the finances for the charter schools, invoiced to the charter schools and paid out to companies they owned and controlled for educational and instructional services that were not provided,” the indictment states.

McManus and Schrock and their subordinates opened 19 virtual charter schools across the state — vehicles that the pair used to funnel state funds into their own pockets, prosecutors said.

Here’s how the men created these schools, according to the indictment:

Charter schools are independently-run public schools. To open one in California, a petitioner needs to get authorization, or approval, from a school district, a county school board or from the State Board of Education.

McManus and Schrock targeted low-enrollment school districts, like Dehesa, to seek authorization, Stephan said; small districts would be eager for the revenue boost that comes from oversight fees, which districts get for every charter school they authorize.

Critics say that while small districts are incentivized to seek charter school authorization business, they’re often poorly equipped to provide oversight.

The indictment said McManus and Schrock sought small-district authorizers while at the helm of A3 Education, their non-profit that claims to provide services to charter schools.

On official paperwork for the charter schools, McManus and Schrock listed themselves, some of the co-defendants and even family members as the officers or board members of charter schools, including Schrock’s brother-in-law, their wives and Schrock’s daughter, prosecutors said.

According to the indictment, McManus, Schrock, Johnson, Robert Williams, and a small number of associates were listed as president, CEO, CFO, secretary, school administrator or board members of the various schools. For one school, they listed two people as officers without their knowledge, prosecutors alleged.

When they submitted annual business filings and opened bank accounts for some of their schools, the defendants used personal addresses or the Newport Beach address of an accounting business owned by Williams, the indictment said.

Many of the schools also shared the same auditor, who submitted audits that said the schools were complying with spending and attendance accounting rules, according to the indictment.

Prosecutors said that the online charter schools provided little or no services to many of the hundreds of students “enrolled” in them.

Traditional public schools make their finances are made public.

Prosecutors say McManus and Schrock told employees to keep A3’s finances quiet. McManus once told an employee to describe A3 as a “vendor” selling to charters, rather than a charter management organization, according to the indictment.

Some people did raise red flags about A3’s schools. According to the indictment an outside auditor, Chris Thibodeau of Squar Milner, brought up concerns about potential fraud in an A3 charter school in December 2017.

Thibodeau noticed that while A3 Education was listed as a vendor for Cal Prep Sutter Charter Schools — which McManus and Schrock oversaw — there was no record in the school board’s minutes that a contract between Cal Prep Sutter and A3 had ever been approved, according to the indictment. Cal Prep Sutter was authorized in Meridian, Calif.

After learning of Thibodeau’s concern, Schrock allegedly doctored meeting minutes to show the contract was approved two years prior, or 2015, even though Williams told Schrock he shouldn’t fabricate board minutes that Thibodeau already had copies of, prosecutors said.

“Can’t have two sets of minutes for a meeting,” Williams emailed to Schrock, the indictment said.

According to the indictment, Thibodeau filed an annual audit of Cal Prep Sutter in January 2018 that listed several findings: the charter school had engaged in financial conflicts of interest, it had made check disbursements with a signature of someone who wasn’t part of school management or the board, and it had no documentation for several invoices or accounting entries.

Thibodeau noted his concerns and Cal Prep Sutter hired a new auditor to conduct its annual audit, prosecutors said. That auditor was the one who allegedly filed audits for several other A3 charter schools, saying those schools were in compliance, the indictment states.

To shuttle the money from the charter schools to themselves, Schrock and McManus formed three companies, prosecutors said: A3 Consulting, Global Consulting Services and Mad Dog Marketing.

They claimed in business filings that these companies were based in Wyoming, and when they opened bank accounts for the companies, they told the bank they would not be doing business in California, prosecutors said.

The companies’ bank account records did not list the kinds of business expenses that would typically match the invoices tied to the schools, prosecutors said.

The District Attorney’s Office said the companies, owned and controlled by McManus and Schrock, raked in more than $50 million from charter schools also controlled by McManus and Schrock.

Those companies then allegedly wired at least $8.1 million to personal bank accounts for McManus, Schrock and their wives, including a National Australian Bank account for McManus and charitable trust accounts, according to prosecutors, and another $1.6 million paid for a home for McManus.

Alleged overpriced oversight

Prosecutors alleged a different type of scheme in which Dehesa Superintendent Nancy Hauer overcharged charter schools for oversight fees.

In California charter school authorizers like Dehesa are supposed to collect fees to cover their cost of overseeing the schools and holding them accountable. Often the fees range from 1 to 3 percent, studies show.

In Hauer’s case, she is accused of collecting more than $2 million in oversight fees, which is more than actual costs incurred and more than the Dehesa district’s payroll budget, according to Stephan and the indictment.

As Dehesa’s charter schools’ reported enrollments rose, so did Hauer’s fees, prosecutors said, which was a disincentive for the district to provide appropriate oversight.

Hauer denied the charge against her. She was put on paid leave by the Dehesa School Board Friday.

A trial date has not yet been set in the cases. Most defendants are due back in court June 11 for a status hearing.

According to the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department website, Schrock remained in custody Saturday afternoon, with bail set at $1.5 million.

The website said Richard Nguyen and Justin Schmitt, the only other defendants taken into custody Wednesday, were not in custody Friday evening. Their bail had been set at $50,000 each.

A3 Education issued a statement saying it has a new interim CEO and is taking measures to improve its internal controls.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.