The Public Theology of Luis Oviedo

Human Flourishing and the Common Good

Human Flourishing and the Common Good

Does the enhancement of human flourishing contribute to the common good? Yes, according to Gaudium et Spes promulgated by the Second Vatican Council. The common good is “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members relatively thorough and ready access to their own fulfillment.” Without human flourishing at the individual level, there could be no common good at the social level.

So, I ask again: does the enhancement of human flourishing contribute to the common good? Yes indeed, especially if you’re Luis Oviedo.

Let’s take a look at the public theology of Luis Oviedo. Oviedo is concerned about the value of religion in general and the Christian religion in particular. Does religion offer positive practical effects to the wider culture? If religion does offer positive practical effects, does this count toward its credibility? Is this the way we should measure the value of religion in the public square?

Meet Luis Oviedo

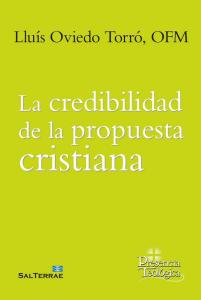

Lluís Oviedo Torró, OFM, was born in Spain in 1958. Today he is full professor of Theological Anthropology at the Antonianum University in Rome. He is also invited professor in Fundamental Theology at the Theological Institute of Murcia, Spain. His research focuses on the dialogue between theology & science.

These days Oviedo edits a fine online quarterly, Reviews in Science, Religion, and Theology. RSRT is published by ISSR (International Society of Science and Religion) along with ESSSAT (European Society for the Study of Science and Theology). He has just published a new book in his native Spanish, La credibilidad de la propuesta Cristiana.

I introduced Luis Oviedo in a previous Patheos post, “Religion Decline and Public Theology.” Now, let’s take a broader look.

Luis Oviedo as Public Theologian

Recall how frequently I aver that public theology is conceived in the church, rationally refined in the academy, and offered to the wider culture for the sake of the common good. Is Luis Oviedo a public theologian in this sense?

Yes. We can speak of Luis Oviedo as a public theologian on two counts. First, Oviedo incorporates science into his theological method. Nothing is more public than science. I have contended for some time that engagement with science is one of the important tasks of the public theologian.

Second, Oviedo evaluates religion according to its value for wider society. Religion is valuable, Oviedo says, because of its positive prosocial effects in enhancing human resilience in the face of crisis and in contributing to human flourishing. Beliefs matter.

Note what Oviedo is not doing. He’s not measuring religion according to its faithfulness to Scripture or loyalty to tradition. Or even its truth value. Rather, according to Oviedo, religion is good insofar as it contributes surplus value to human well-being.

Question. Luis, you are calling for a new perspective for theology. You are calling for fresh studies on religion and coping, resilience, well-being, and flourishing. How do you define human flourishing? And how can theology contribute?

Luis Oviedo. There are several definitions of human flourishing. This has been a topic that Martin Seligman and others were popularizing after 2000. It’s now becoming a mark for anthropological improvement and positive psychology.

For me human flourishing refers to the development of those capabilities or potentials every person possesses, but that need to be worked out with some investment. Potentials need actualization. Otherwise, these capacities will languish and remain inactive. Flourishing means fulfillment of potential.

This contemporary notion of flourishing revives the biblical idea of talents as well as the medieval idea of character formation. Today, flourishing is more linked to positive psychology. And it is more culturally fashionable than the former versions.

Human flourishing is about investing in our own personal improvement. To flourish we must avoid falling into negative tendencies. In this sense human flourishing incorporates cultivating virtue and avoiding vice and sin. And indeed, several authors have linked the flourishing ideal with the Aristotelian model of virtue.

For the theologian, incorporation of human flourishing is quite natural when the above genealogy is assumed. Hence, there would be little new when testifying that Christian faith has always supported the cultivation of virtue. This is especially the case in the medieval elaborations. But, of course, our medieval virtue theorists referenced divine grace as the true cause for such personal improvement.

Charles Taylor has complained against the occasional drift in Christian tradition toward a moralistic and monitoring system. Taylor postulates a better model aimed at achieving “fullness of life”, or the best in our living conditions.

Something similar can be found in the religious studies scholar Gavin Flood and his approach to the religions as ways to exalt life, or to heal its wounds. In that sense, the pursuit of flourishing connects with deep traditions in religious faith and praxis.

The goal of human flourishing represents today a very fresh ideal close to some models of happiness or meaningful life. The ideal of human flourishing is a more clear and understandable way to express the Christian idea of salvation. Better than salvation, human flourishing is something not delayed to a far future. Rather, human flourishing can be an experience achieved in the present conditions.

Question. In today’s world, in which almost everything is already invented and is so well served by secular means, how can we as public theologians or as church pastors contribute anything of value to the common good?

Luis Oviedo. This is an important issue that needs to be addressed by the theologian with the help of auxiliary sciences. What is the function of religion? During recent decades it has become less clear. The value of religion is less clear when apparently all the needs we could experience were covered by human or secular means. This seems to make religion almost redundant or useless.

I ask rhetorically: other than its aesthetic contribution, does religion offer anything of value to secular society? Should the diminishment and elimination of religion become our expectation?

No. The empirical evidence does not support – thus far – such an expectation. Many indicators suggest that in several cases the withdrawal of religion does not automatically lead to better living standards or quality of life. Some Scandinavian countries might be an exception. But we are less sure in many other settings that the diminishing of religion contributes to enhanced human flourishing. In any case, the question still looms: what is the role of religion in Western societies?

My answer is this: the function of religion is to provide spiritual communication with what transcends us. As German sociologist Niklas Luhmann puts it: to keep open the access to a transcendent dimension, beyond sheer material reality, and to render such an access a salvific experience.

Such an openness to transcendence can furnish several positive prosocial outcomes: meaning and purpose for personal and social conditions; coping and resilience; and enhancing prosocial attitudes. In short, openness to transcendence has the practical effect of contributing to human well-being and even human flourishing.

Does this contribute to the common good? Our contribution to the common good has to do with caring for such transcending capacity – and for its derived outcomes. From such a point of view, theologians and pastors can exert a more accurate critical view against false views or counter-adaptive trends, or to check about commonly shared beliefs and expectations, often being subject to manipulation and populist biases. But all these makes sense to the extent that we continue to vindicate an alternative reality, of greatest good, beauty and truth.

Question. You believe that theology could benefit by adopting empirical methods, even that of the new scientific study of religion. What could the theologian learn?

Luis Oviedo. I have been advocating over the last 20 years for a more empirically driven theology that is more committed with sciences. I find special value in the new scientific study religion.

This stance entails clear risks. For example, empirical data could disqualify religion as a source of positive prosocial outcomes. Or science could render religious faith less credible, especially in its mysteries. For a risk-averse theology, it is understandable that theologians might avoid such dangerous venues.

However, the theologian like the scientist should engage in a trial-and-error method that leads to correction.

My own experience with science in recent years has been very positive. I like the scientific way of gathering data and engaging in empirical studies with teams of committed colleagues. This method has allowed us to better describe how religious faith and practice assisted people during the Covid 19 pandemic. We could also demonstrate how religion became a coping and resilience factor for Ukraine war refugees. We’ve seen how religion helped adolescents to become more concerned and careful about elderly.

I have felt deeply connected with a big scholars’ class away from the theological academic area and devoted to these studies. I have felt that theology could grow in contact with all this huge research body, and that theologians could find a very common language with people working in the therapeutic and social sciences.

These scientific analyses of religion’s practical prosocial effects have provided me with way to better express the credibility of Christian invitation to faith. It can be demonstrated that faith improves the quality of life for many people. That faith contributes to human flourishing becomes, the main argument for religion’s meaning and value.

Question. You sound like a pragmatist. How do you handle the truth question.?

Question. What else would you like to say?

Luis Oviedo. I am convinced that we theologians still have a role to play in the wider culture. That role includes promoting the practical value of religion to provide resilience and flourishing capacity.

To foster the replacement of theology in academia with a so-called “neutral” scientific study of religion would be a mistake. Such a “scientific” approach would never be able to help anybody to cope with distress or to encourage resilience after adversity. Nor would a scientized approach to religion assist anyone in loving and caring for those who need our attention.

Theology is a form of knowledge. Or better, wisdom. Theological wisdom is aimed at encouraging people to live better lives. Theological wisdom cultivates loving.

Reflections on Human Flourishing and Luis Oviedo

What is distinctive about Luis Oviedo is twofold. First, he measures the value of religion by extra-theological criteria. He exacts a practical criterion that can be scientifically measured, namely, religion’s contribution to human prosociality, especially resilience in the face of crisis.

Then, secondly, when religion succeeds at meeting this criterion, it counts towards religion’s credibility. A religion that makes a prosocial contribution is valuable not just to the church but to the wider culture.

Rather than appeal to a measure of value formulated within the church, Luis Oviedo appeals to a criterion that can be publicly measured. I can appreciate this, because in this way Oviedo’s theory values religion when it contributes to the public good.

Yet, I suspect that this may be inadequate. As a systematic theologian, I believe religious claims should be measured according to their truth. Oviedo does not avoid the truth question, to be sure. But he measures truth according to effect.

The now late Robert Bellah, sociologist of religion at the University of California at Berkeley, simply threw up his hands to exclaim: “To put it bluntly, religion is true.” (Bellah 1970, 253). That’s religion’s value, according to Bellah. It’s true. Now, just what “true” means here only begins a complex examination, to be sure. Yet, for this sociologist, truth matters.

When a Christian claims that God is gracious, I want to know if this is true or not. When a Christian claims that our gracious God justifies us by forgiving sins and then promises our resurrection to everlasting life, I want to know if this is true or not…about God. Truth or falsity here would make a huge difference in what I believe and how I live. Even if my personal life would turn out to be a failure, it might still be true that God is gracious.

Still, I ask with Oviedo, does belief in a God of grace make daily living better for the person of faith? Does faith itself enhance human flourishing? Yes, indeed. I’ve argued this extensively. Why? Because the conviction that one’s sins are forgiven sustains courage in the pursuit of loving one’s neighbor. The experience of divine grace in our life comforts us when facing the possibility of mistaken judgment. If we get it wrong, we need not feel a loss of self-worth. Trust in God’s grace sustains integrity, joy, and peace of mind. Freedom too.

In a sense, these fruits of the Spirit–love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control (Galatians 5:22)—contribute to human flourishing. The common good is enhanced when society is made up of persons expressing the fruits of the Spirit. These fruits count as a practical prosocial effect by which we can value the Christian faith.

Conclusion

As a long time admirer of ESSSAT and my European colleagues in Theology & Science, I continue to applaud Luis Oviedo’s abiding leadership in this important field.

▓

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). This month he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2023). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

His fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

▓

References

Bellah, Robert. Beyond Belief. New York: Harper, 1970.

Oviedo, Luis Torro. La credibilidat de la propuesta cristiana. Madrid: SalTerrae, 2022.

Peters, Ted. The Voice of Public Theology. Adelaide: ATF, 2023.