overview

In 1970, less than a year after Stonewall, the police raided the Snake Pit bar and detained many people at the local police station.

After one person attempted to escape and was impaled on a fence, the Gay Activists Alliance and Gay Liberation Front quickly assembled a protest march, the results of which demonstrated the strength of the recently formed gay rights organizations and inspired more people to become politically active.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

Only eight months after the Stonewall uprising, in the early morning of March 8, 1970, police raided the Snake Pit, a gay-run, non-Mafia, after-hours bar in the basement of a Greenwich Village apartment building (according to Bob Damron’s 1970 Address Book, an annual gay travel guide, the Snake Pit was located below the Texas Chili Parlor). The raid was led by NYPD Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, who had also led the ill-fated raid on the Stonewall.

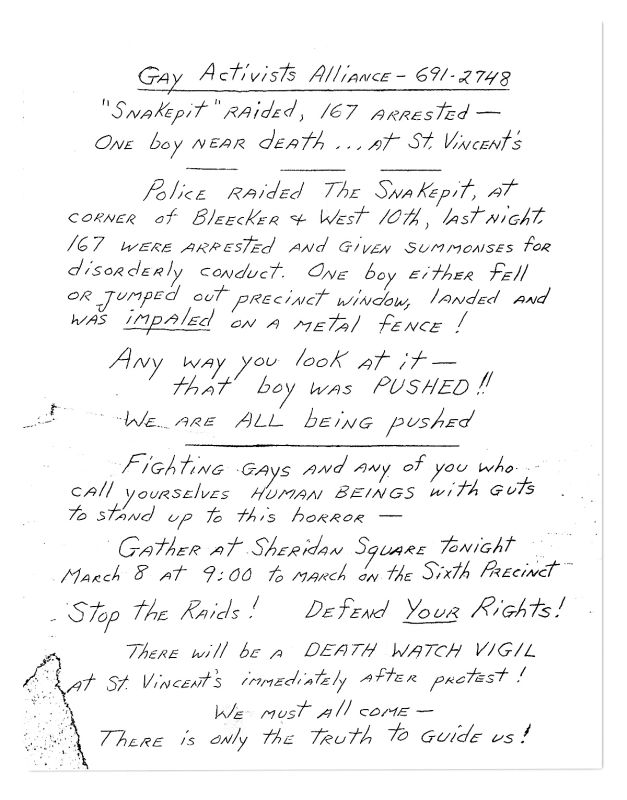

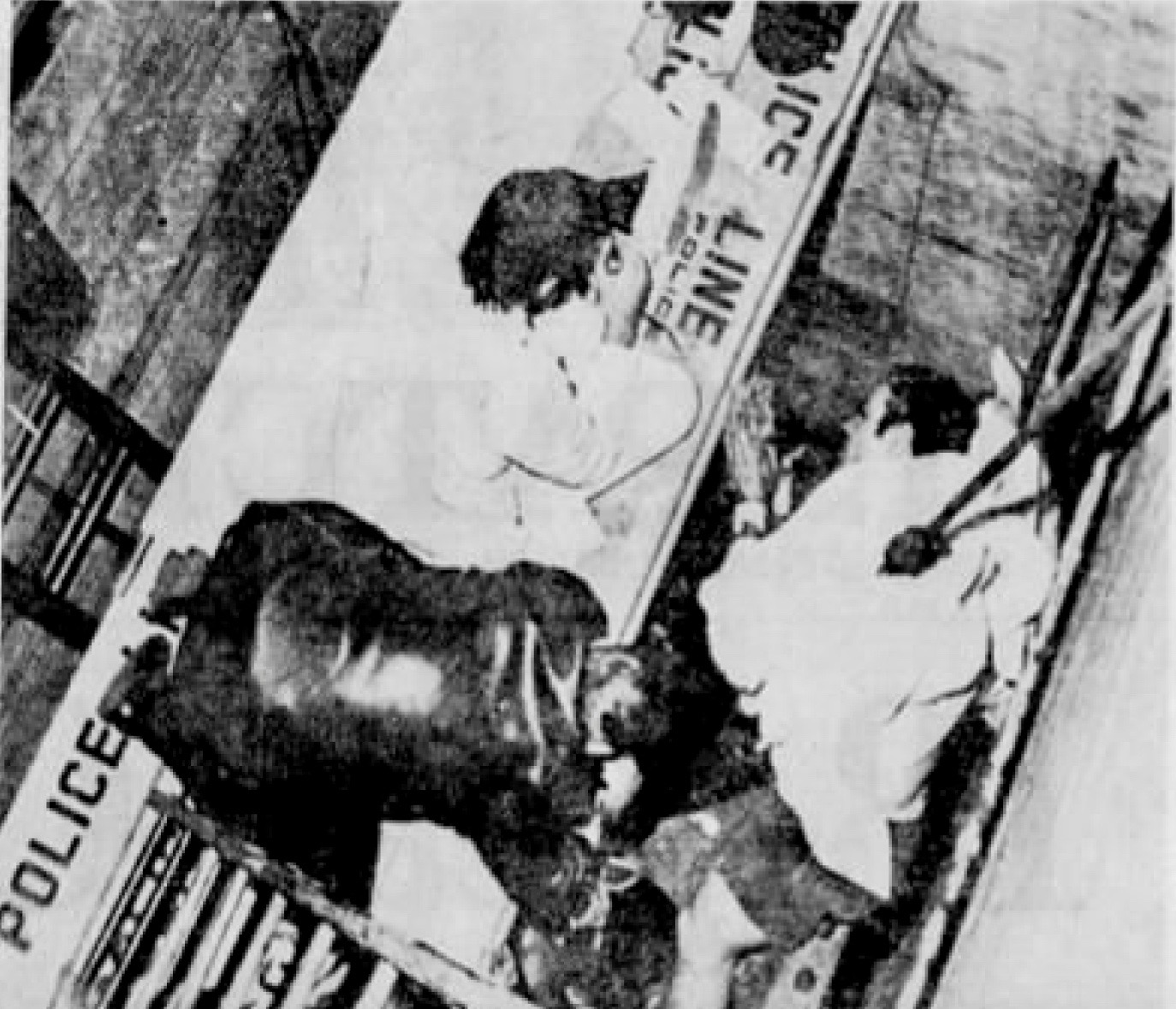

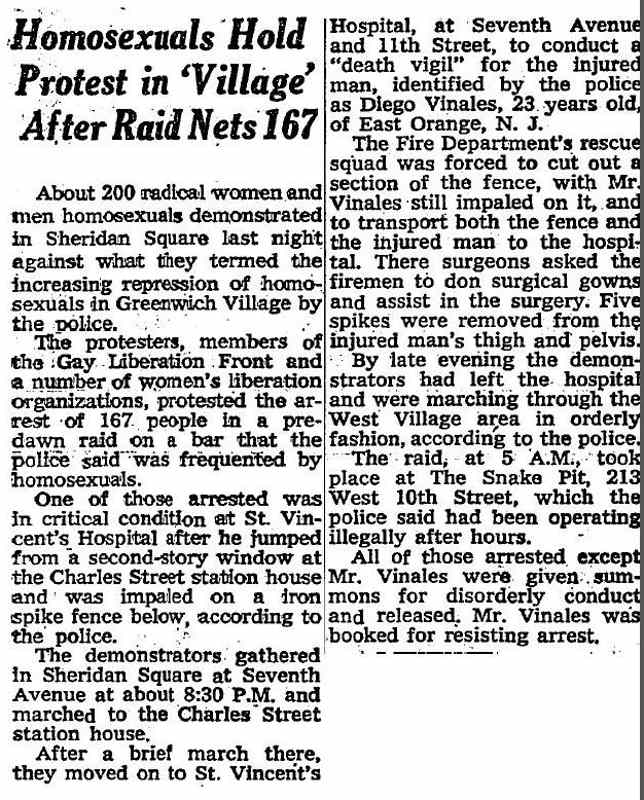

Fearing similar rioting from the large crowd of male patrons, the police arrested 167 people, who were taken to the 6th Police Precinct Station House at 135 Charles Street. Argentinian immigrant Diego Vinales, who was only 23 years old and visiting a gay bar for the first time, panicked over the possibility of deportation since his visa had expired, tried to escape from the third story of the jail, and was impaled on the iron fence below. He was cut loose along with part of the fence by firemen, taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital and survived, but word spread that he was dead or dying. A number of arrested men found an empty police office and started making phone calls to Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) leaders and to the press. The Daily News became interested in the story.

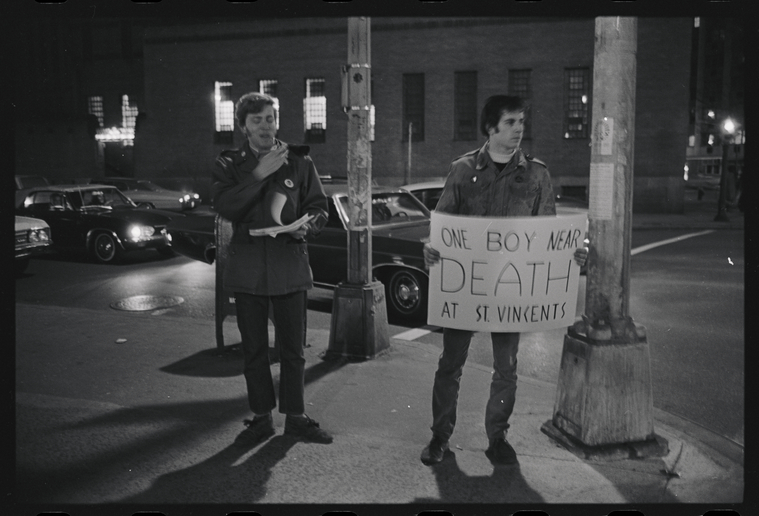

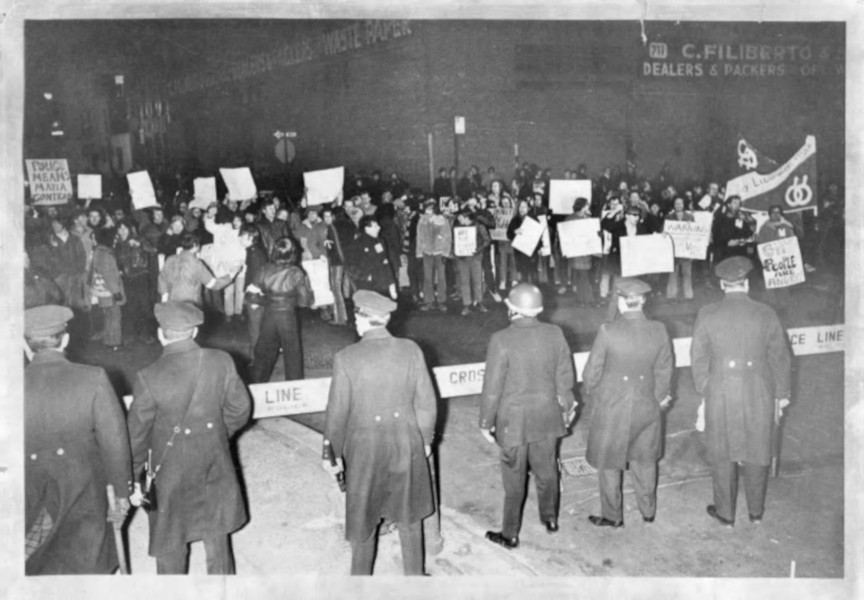

GAA organized a quick response, and distributed flyers in Greenwich Village and on the Upper West and Upper East Sides. Joined by the Gay Liberation Front, along with Women’s Liberation, Homosexuals Intransigent!, Homophile Youth Movement, and Yippies, at 9:00 PM that evening, GAA led an angry protest by a crowd numbering around 500 people, who marched from Christopher Park to the police station.

Any way you look at it – that boy was PUSHED. We are ALL being pushed.

A candlelight vigil was also held at St. Vincent’s. All of the disorderly conduct charges were soon dismissed, except for Vinales’ for resisting arrest.

This incident, which received much media coverage, is credited with greatly inspiring more LGBT people to become politically active, including many who had not following Stonewall, such as future film historian Vito Russo, future GAA president Morty Manford, and educator Arnie Kantrowitz. It also demonstrated the strength of the recently formed gay rights movement organizations. The success of the protest is credited with influencing GAA in the direction of planning many political confrontations for gay rights, which became known as “zaps.” Vinales remained hospitalized at St. Vincent’s for three months. Charges against him were dropped by the City in June, but he still faced the U.S. Immigration Bureau. While no one knows what happened to him afterward, journalist Arthur Bell did visit him at his home in New Jersey later that year.

Entry by Jay Shockley, project director (March 2017).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Horenburger & Straub

- Year Built: 1903

Sources

Aelarsen, “Stonewall: There’s Got to Be a Morning After,” An Historian Goes to the Movies blog (October 2015), bit.ly/2gtBR1i.

“Aftermath of the Snake Pit,” DOB Newsletter, April 1970, 2-3.

Arnie Kantrowitz, Gay Activists Alliance, Meeting Minutes, June 18, 1970.

Arnie Kantrowitz, Under the Rainbow: Growing Up Gay (New York: Pocket Books, 1977).

Arthur Bell, Dancing the Gay Lib Blues: A Year in the Homosexual Liberation Movement (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971), 40-42, 49, 106-107.

Arthur Irving [Arthur Bell], “The Morning of the Snake Pit” and “Gay Activists Alliance News,” Gay Power, March 1970.

Bob Damron, Bob Damron’s 1970 Address Book (San Francisco: Bob Damron Enterprises, 1969).

Daniel Hurewitz, Stepping Out: Nine Walks Through New York City’s Gay and Lesbian Past (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1997).

David Carter, Stonewall: the Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004).

Elizabeth A. Armstrong and Suzanna M. Crage, “Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth,” American Sociological Review (October 2006).

“Firemen Saw Spikes From Man In Operating Room,” The Daily Dispatch, March 9, 1970, 2.

Jonathan Black, “The Boys in the Snake Pit: Games ‘Straights’ Play,” Village Voice, March 19, 1970, 61-64.

“Patrons Tell of Raid From Inside” and “500 Angry Homosexuals Protest Raid,” GAY, April 19, 1970.

Philip McCarthy, “Impaled, Saved by Fire ‘Docs’,” Daily News, March 9, 1970, 4.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?