The horror stories are everywhere.

A couple pulls into their Uptown driveway, then watches as a robber drives off in their SUV with their young children asleep in the back. A 60-year-old physical therapist walks out of her house in the 7th Ward and is stabbed to death by a man who takes off in her Honda CRV. A woman is on her way to deliver groceries to her in-laws when two people walk in front of her car and open fire with a rifle, mortally wounding her.

Members of the NOPD investigate the murder by stabbing of Portia Pollock on the 1500 block of North Dorgenois Street during a carjacking in New Orleans, La. Tuesday, June 8, 2021.

It's the year of the carjacking in New Orleans, and things have gotten so bad that residents have begun arming themselves, changing where they drive, and in some cases, making plans to move away.

According to an analysis by The Times-Picayune, there have been 240 carjackings investigated in the city during the last 12 months — 120% higher than the year before and more than 160% above the yearly average over the last decade.

Scholars say the uptick is in line with trends unfolding in virtually all major cities across the United States, where homicides, non-fatal shootings and other violent crimes have also surged.

No single factor explains it, experts say, though the mental strains associated with navigating the coronavirus pandemic might be contributing. So might questions in some communities about the legitimacy of law enforcement following the slayings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other Black citizens at the hands of police officers, which sparked widespread protests last year.

New Orleans police and a working dog gather around the 1800 block of Tulane Avenue near University Medical Center after an armed carjacking suspect fled in New Orleans, La. Monday, Dec. 14, 2020.

The fact that the city's carjacking epidemic isn’t unique serves as little consolation to business leaders anxiously awaiting the return of tourists and locals who have been victimized during the yearlong spree.

Ryan Sibley said she regretted moving to New Orleans from Washington D.C. the moment she helplessly watched a robber hop into her family car — with her two children sleeping inside — and speed off in April.

Parents say they left vehicle running, kids inside, while they tried to unlock gate at home

Sibley and her husband, Patrick Madden, got out of their running vehicle for mere seconds to unlock the gate at their Uptown home to make putting their children to bed after a beach trip go as smoothly as possible. The thief ditched the car a couple of blocks away, and the children were physically unharmed. While they have no immediate plans to relocate, Sibley said her family is out of here as soon as that is feasible.

“This is not a safe place,” Sibley said recently. “If your kids can be stolen while in the back seat of your car, in an instant, for no reason, that’s the worst thing that can happen.”

Meanwhile, Ryan Clute was loading donated toys into his girlfriend’s running car in February when someone slammed his head against the vehicle and drove off with it in St. Claude. He said his car was later found, riddled with bullet holes and practically totaled, and he now sees every stranger as a potential threat.

Clute has obtained a permit to carry a concealed gun, and he keeps his weapon on him as much as possible.

“It’s a really sh---y way to live, assuming the worst in people,” he said. “It’s not in my nature to want to do that, but unfortunately, it’s the only way to ensure I am not caught off guard.”

Family, friends and neighbors gather in front Portia Pollock's home to celebrate her life and the power of community and love on N. Dorgenois Street in New Orleans Wednesday, June 16, 2021. Portia was killed in front of her 7th Ward house last week by Bryan Andry. (Staff photo by David Grunfeld, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

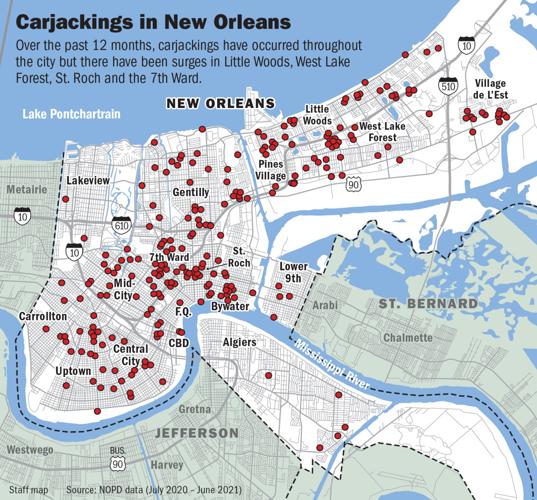

While carjackings have occurred in most corners of the city, the newspaper’s analysis shows that a person's chances of being carjacked is higher in certain areas.

The Little Woods neighborhood in New Orleans East has been the hardest-hit by far, with at least 27 carjackings since July 2020 — more than 11% of the total reported. It has also consistently had the highest number of carjackings in the past decade.

The 7th Ward ranks second on the list, with at least 15 carjackings reported, up from nine in the prior 12 months. During the last decade the neighborhood has consistently ranked in the top five for carjackings.

The Central Business District is also in the top 10 worst neighborhoods for carjackings, despite counting on a high concentration of police patrols, given its proximity to the French Quarter.

The statistics also show that drivers aren't always protected by favoring well-lit roadways with relatively high volumes of traffic.

One in five carjackings over the last year have occurred on Claiborne Avenue, the Interstate 10 exits and service road in New Orleans East, and either on or near Chef Menteur Highway and St. Claude Avenue.

A rash of carjackings at local gasoline stations — lit up and jam packed with surveillance — prompted some to download a mobile app which delivers fuel to people’s homes. City Council Criminal Justice Committee chairman Jay Banks said his neighbor got the app after she was carjacked herself.

In a break with his campaign rhetoric, Orleans Parish District Attorney Jason Williams on Monday announced a second-degree murder indictment a…

Perhaps more than other violent crimes, such as homicides and non-fatal shootings, carjackings frequently involve attackers and victims who encounter each other randomly. And there’s always the potential for a carjacking to escalate into a shooting, stabbing or killing.

High-profile examples this year include the death of Anita Irvin-LeViege, a certified professional medical coder and human resources director who was delivering groceries to her in-laws when she was shot to death by two teen boys during a botched carjacking attempt Jan. 3, according to authorities. On June 8, police have said, physical therapist and Congo Square drummer Portia Pollock was fatally stabbed outside her home by a man who stole her car.

Visibly frustrated New Orleans City Council members, under pressure to respond to high violent crime rates, held a hearing Wednesday to public…

New Orleans police arrested suspects in both cases. In a statement, Deputy Superintendent John Thomas, who runs the department's field operations bureau, said such arrests demonstrate the impact of the agency's Violent Crime Abatement Investigation Team.

"We will continue to work to remove violent offenders from the streets," Thomas' statement said.

But New Orleans police have repeatedly said the fight to curb carjackings doesn’t end with their officers, arguing that the ball is now in the hands of prosecutors and judges who must work to bring the defendants to justice and send the message that their alleged misdeeds are not acceptable.

Banks echoed that point this week, saying, “You have to hold them accountable.”

Beyond that, specific ideas to get a grasp on carjackings and other violent crimes are hard to come by.

In a statement, District Attorney Jason Williams touted his office's participation in a multi-agency unit whose aim is to build long-term cases that incapacitate multiple defendants at once and bring "more relief" to neighborhoods that way.

Williams is also planning a summit to bring at-risk youths together with educators, advocates, social workers and other legal system stakeholders.

"This effort of investment and crime prevention is critical, because once the criminal legal system is involved, it’s too late,” Williams' statement said.

Banks agreed that doubling down on recreation and mentoring programs that keep young people occupied is essential. So are job opportunities that pay better than crime might. But expanding those programs takes significant funding and time, which is frustrating when the problem is “way out of control,” Banks added.

Whatever potential solutions are out there, they won’t be particularly easy to identify or implement, according to two criminologists who have been studying the situation.

As major cities closed down to slow the spread of the coronavirus, property crimes such as home burglaries and shoplifting declined significantly, said University of Missouri-St. Louis criminology and criminal justice professor Richard Rosenfeld.

Then, when restrictions were lifted, violence shot up across the country. That means the factors driving the increase aren’t particular to a locality, and so the solutions won’t be local either.

“It’s … troubling,” Rosenfeld said.

Despite the size of the challenge, if the city doesn’t begin finding solutions soon, it runs the risk of “killing the golden goose”: the tourism industry, said Dr. Peter Scharf, a criminologist at the LSU School of Public Health.

“At what point do people stop coming to the hotels?” Scharf said. “At what point do you say, ‘Let’s go vacation in New Orleans,’ and others look at you and say, ‘You’re nuts, I don’t want to get shot or carjacked.’”

A man tried to carjack an on-duty, plainclothes New Orleans police detective Sunday at a Lower Garden District intersection, apparently not re…