Why your arm might be sore after getting a vaccine

Pain and rashes are normal responses to foreign substances being injected into our bodies. But how much pain you experience after a shot depends on a lot of factors.

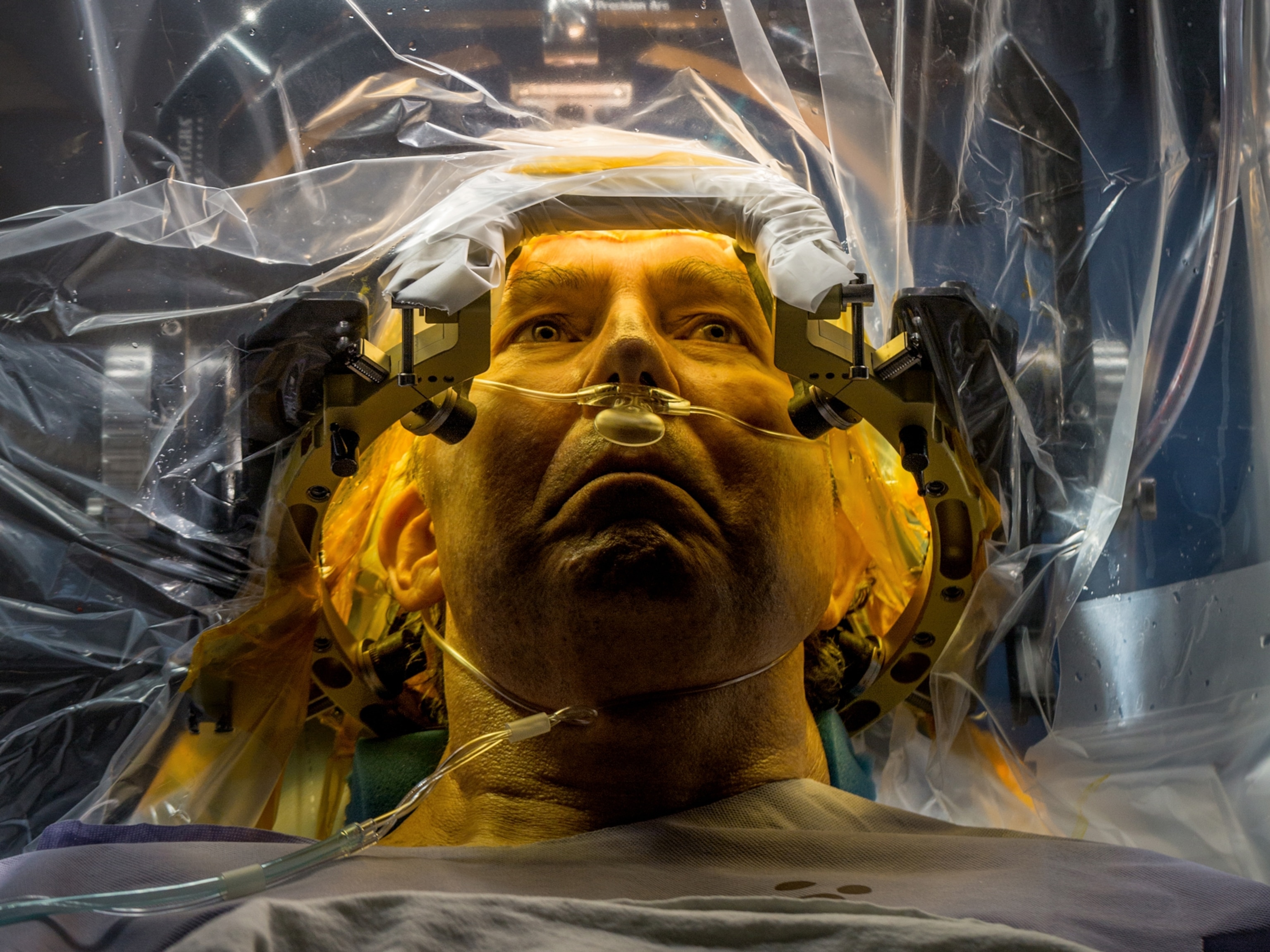

For most COVID-19 vaccine recipients, the poke of the needle is no big deal. In the hours afterwards, however, many go on to develop sore arms, according to anecdotal reports and published data.

That common side effect is not unique to COVID-19 vaccines. But as the United States undergoes its first mass vaccination campaign in recent memory, the widespread prevalence of arm pain is sparking questions about why certain shots hurt so much, why some people feel more pain than others, and why some don’t feel any pain at all.

The good news, experts say, is that arm pain and even rashes are normal responses to the injection of foreign substances into our bodies. “Getting that reaction at the site is exactly what we would expect a vaccine to do that is trying to mimic a pathogen without causing the disease,” says Deborah Fuller, a vaccinologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, in Seattle.

Given the many intricacies of the immune system and individual quirks, not feeling pain is normal, too, says William Moss, an epidemiologist and executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in Baltimore. “People can develop protective immune responses and not have any of that kind of local reaction,” he says.

Danger signals

A variety of vaccines are notorious for the soreness they cause around the injection site, and the explanation for why begins with so-called antigen-presenting cells. These cells are constantly on the prowl in our muscles, skin, and other tissues. When they detect a foreign invader, they set off a chain reaction that eventually produces antibodies and long-lasting protection against specific pathogens. That process, known as the adaptive immune response, can take a week or two to ramp up.

Meanwhile, within minutes or even seconds of getting vaccinated or detecting a virus, antigen-presenting cells also send out “danger” signals that, Moss says, essentially say, “‘Hey, there's something here that doesn't belong. You guys should come here. We should get rid of it.’”

This rapid reaction, known as the innate immune response, involves a slew of immune cells that arrive on the scene and produce proteins known as cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins, which recruit yet more immune cells and have all sorts of physical effects, Fuller says. Cytokines dilate blood vessels to increase blood flow, causing swelling and redness. They can also irritate nerves, causing pain. Cytokines and chemokines induce inflammation, which is also painful. Prostaglandins interact directly with local pain receptors.

The innate immune response doesn’t stop at the arm. For some people, the same inflammatory process also can cause fevers, body aches, joint pain, rashes or headaches.

The reason some vaccines cause more symptoms than others—a tendency called reactogenicity—is because of the strategies and ingredients they employ. The vaccine for measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), for example, is made from live, weakened forms of the viruses that intentionally cause a mild form of infection and stimulate the body’s innate immune response, leading to a variety of symptoms, including sore arms. Other vaccines, including some flu shots, introduce inactivated viruses. The hepatitis B vaccine presents parts of the virus along with chemicals called adjuvants that are designed to get antigen-presenting cells riled up and boost the adaptive immune response.

Those substances, Fuller says, “are the first trigger your body gets to say, ‘Something is going on here, and I need to respond to it.’”

Follow vaccine developments with our vaccine tracker.

Sore-arm profiles

All three FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccines are delivered via a needle into the arm, and all cause the same kind of poking pain that comes with a quick stab. After that, their post-vaccination arm-soreness profiles vary, according to company data compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After the first dose of the two-shot Moderna regimen, 87 percent of people under 65 years old and 74 percent of those 65 and up in clinical trials reported localized pain, echoing research that shows a decline in immune reactivity with age. After the second shot, those numbers rose to 90 percent of the younger age group and 83 percent of older people.

The first Pfizer shot, likewise, caused a lot of sore arms in trials: 83 percent of people up to age 55, and 71 percent in older people. Shot-two soreness occurred in 78 percent of the younger group and 66 percent of the older one.

The one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine caused less arm pain—59 percent of people under 60 and 33 percent of older people.

The elevated rates of arm pain with the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines might have something to do with the technology they use, Fuller says. Unlike J&J, which uses a modified virus to deliver a gene that directs our cells to make the SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein, Pfizer and Moderna deliver instructions for making the protein via mRNA. Researchers have long known that RNA, which some viruses use to carry their genetic material, is a potent trigger of the innate immune system.

In fact, she says, when scientists started considering mRNA as a vaccine strategy some 30 years ago, they rejected the idea, in part because of concerns that it would overstimulate inflammatory pathways. They were also too unstable to work. More recent breakthroughs in the ability to modify mRNA and encapsulate it in lipid nanoparticle coatings made the new generation of vaccines possible, but common adverse reactions remain relatively high. The nanoparticle coating itself acts as an adjuvant that likely contributes to local reactions, Fuller adds.

A more surprising reaction

Soon after the Moderna vaccine was approved in December, allergist and researcher Kimberly Blumenthal began receiving photographs of arms from colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The photos showed large red splotches around patients’ injection sites. Some people had a second rash below the first. Some had red marks shaped like ringed targets. Some rashes appeared on elbows and hands.

After accumulating a dozen images, Blumenthal wrote a letter for the New England Journal of Medicine with the goal of alerting physicians—and reassuring them—about the potential for delayed reactions to the vaccine. Some doctors were prescribing antibiotics for suspected infections, but the pattern she saw suggested that antibiotics were not necessary.

Unlike the rare and dangerous anaphylactic reaction that can happen immediately after injection, delayed rashes don’t usually require treatment, Blumenthal says. In a biopsy of one patient, she and colleagues found a variety of T cells, suggesting a type of hypersensitivity. Delayed rashes are known to show up occasionally after other vaccines too, she adds, and they can be a sign of hypersensitivity or a normal part of the immune response. Researchers don't yet know which is happening with the Moderna vaccine. In this case, they may appear especially common because so many people are getting vaccinated at once.

Still, late-onset rashes might be more common than official data suggest. In clinical trials, Moderna reported them in 0.8 percent of vaccine recipients four or more days after the first shot, and in 0.2 percent of people after the second dose. But delayed rashes tend to appear an average of seven or eight days after injection, and initial trials weren’t designed to pick up on all symptoms that showed up that late, Blumenthal says, likely because they weren't expecting them.

She has created a registry for physicians to report delayed rashes and is working on one for patients, in order to understand the range of what they can look like and detect any patterns about which rashes might be more worrisome. “Since we published this,” she says, “my in-box has been flooded with photos.”

Who feels the pain?

Among the people I know who have been vaccinated so far, some have felt little to no soreness. Others couldn’t sleep for days because of the pain. One friend who got the Pfizer shot said it felt like he had been punched by a professional boxer.

For symptoms like arm pain, individual variation is the norm, and studies suggest multiple explanations. Age can diminish immune reactions, for example. So can higher BMIs, found a recent preprint study.

Genetics likely plays a role in varied and complex ways, experts say. And gender matters, too. In addition to a vast literature on sex differences and immunity, women appear to experience more side effects then men in response to a COVID-19 vaccine, according to emerging evidence, even though men seem to suffer a larger impact from the virus itself.

Pain perception is another X-factor. Everyone processes pain signals differently. And fear and anxiety can exacerbate the feelings of pain, says Anna Taddio, a pharmacy professor who studies pain related to medical procedures in children at the University of Toronto.

Studies show that fear of needles is an important barrier to vaccination for a significant number of people. A quarter of adults reported being afraid of needles in a 2012 study by Taddio and colleagues. According to one new analysis of 119 published studies, 16 percent of adults and 27 percent of hospital employees avoided flu shots because of needle fears.

Amidst efforts to get people vaccinated as quickly as possible, public health officials often overlook opportunities to make the experience more positive, says Taddio, who has developed an approach for reducing fear and promoting coping skills to improve the vaccination experience.

And there are plenty of simple ways to make people feel less anxious about needles. Helpful strategies, according to Taddio’s approach, can include reminding people to wear a short-sleeve shirt to the clinic to make it easy to access their arms; allowing them to bring someone for support; encouraging the use of distractions; deep breathing and topical anesthetics; and inviting people to ask questions so that they feel informed and prepared.

She also recommends that providers and public health officials talk about vaccines in neutral terms—emphasizing the ability to get protection from the coronavirus instead of scaring people with phrases like “shots in arms.”

“You can talk all you want about the COVID vaccines and how safe they are, but we’re not addressing the underlying issue for a whole chunk of people,” she says. “Where do you hear about how we're going to make this comfortable for you?”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest