As the surge in monkeypox and another Covid-19 variant continue to dominate headlines, another public health threat quietly looms – one that particularly affects women as they age and has worsened considerably during the pandemic – loneliness.

Yes, that’s right. Loneliness is becoming a public health emergency, so much so that countries like Japan and the United Kingdom have appointed Ministries of Loneliness to tackle the problem in recent years.

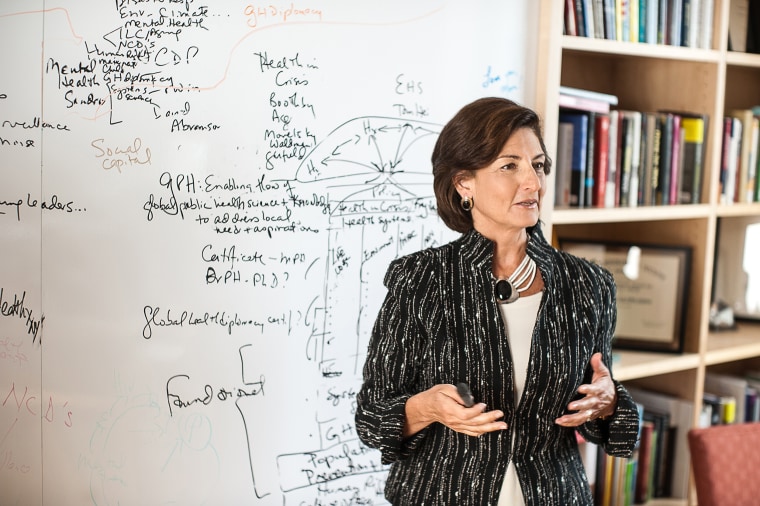

As a medical doctor and public health expert who has spent decades as a geriatrician caring for older adults, and a scientist studying the factors that create health and wellbeing in aging women versus men, we need to pay attention.

By 2035, older adults (65 and up) will outnumber children for the first time in U.S. history, which means that we will have a larger generation of older women than ever before. This seismic demographic shift will create a new cohort of women who will be uniquely vulnerable to loneliness and its health hazards.

While perceptions of loneliness may vary – home alone on a Saturday night, holidays without social activities, empty nests and widowhood – ample evidence shows that loneliness and social isolation are, in fact, public health emergencies with profound and deadly consequences to our bodies and our society.

Clinically, loneliness is defined as a subjective feeling of pain due to unmet needs for meaningful, satisfying connections to other people, creating a distressing gap between actual and desired relationships.

Social isolation is a measure of social interactions and being physically separated from other people, as many of us experienced during the pandemic.

Chronic loneliness and isolation, independent of each other, can harm both mental and physical health, contributing to conditions such as obesity, inactivity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, anxiety and poor sleep, which increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke, especially for older women.

According to a recent study led by researchers at the University of California-San Diego, postmenopausal women who reported high levels of social isolation and loneliness had a nearly 30 percent increased risk for heart disease compared to women who reported low levels of social isolation and loneliness.

The National Academy of Medicine’s “Global Roadmap for Healthy Longevity,” a new commission I co-chaired, examined the worldwide implications of loneliness and called for large-scale approaches across all sectors. This epidemic is global and growing, with women 65 and older experiencing increased isolation and a more acute sense of relational loneliness – the lack of quality friendships and family connections – than their male counterparts.

While all older adults are at an increased risk of both conditions as their social networks shrink – whether it’s due to loss of family and friends, or not being near them, having no children, being single, divorced, retired, or having fewer activities related to daily living – evidence shows that women will suffer the most severe consequences.

For one, they live longer than men and are less likely to have a partner. That’s compounded by the shrinking of their social network, a greater likelihood of living alone for more years, and a greater risk of poverty in old age, compared to men.

A disease created by modern society

It appears that we have built loneliness into our society and there is evidence that it is “contagious” – that friends of people who are lonely are more likely to be lonely. In many places, long-established neighborhoods where people lived together for generations and knew each other intimately have become distant memories.

Today’s increased mobility and transience have unraveled our close-knit communities and support networks. Our workplace “communities” have also been upended by the gig economy, technology, pandemic-driven remote work, and more frequent job changes.

For older adults, ageism, age-driven segregation in housing, lack of work and volunteer roles, accessibility obstacles, living alone, decreased family roles for older adults and diminished intergenerational contact are among the drivers of loneliness. For older women, (especially older than 80) rates of loneliness are particularly high.

Recognize loneliness and take action

We all may experience short-term feelings of loneliness or isolation at some point. However, these may become chronic issues if they are consistent over longer periods of time. If you or a loved one frequently experience the following symptoms, these could be warning signs to seek help from a medical or mental health professional:

- Difficulty connecting with others, including on a more intimate level;

- Feeling you have no close or “best” friends;

- Feeling isolated or alienated regardless of where you are or who you are with;

- Negative feelings of self-doubt and self-worth;

- Feeling burned out when trying to engage with others.

For women who experience these symptoms, these are my top strategies for combatting loneliness.

- Find the things that bring you meaning or joy and intentionally do them with others.

- Increase social interaction by volunteering in your community to make a difference, such as through Experience Corps, or joining a club; create activities with neighbors where you share interests.

- Consider co-housing opportunities, such as renting a spare room to a college student. Generations United has created such programs.

- Get into a routine of reaching out to friends, family and neighbors, both in-person or virtually.

- Find online opportunities in which older adults connect with each other or even volunteer, such as reading to children online or mentoring.

- Practice self-kindness and develop healthy daily routines and structure during the week.

- Get a pet, or borrow one, if you are able to take care of one.

- Take advantage of public programs for transportation and other services, through community centers or government-sponsored programs.

- Speak to your doctor or a mental health professional.

As a society, we may have built loneliness in, but we can also design it out through societal-level approaches. That means advocating for transportation and technological solutions that foster interaction, environments that enable older adults to be located in the center of the action and enable connection, and social infrastructures that promote engagement, particularly among generations.

If you are a woman or love someone who is, I urge you to take action against isolation in your community, in your family, among your friends. And join the effort to formally recognize loneliness as an urgent public health threat.