Even among healthy individuals, feelings of paranoia are not unusual. In modern psychiatry, we consider paranoia to be a pattern of unfounded thinking, centered on the fearful experience of perceived victimization or threat of intentional harm. This means that a patient with paranoia is, by nature, difficult to engage in treatment. A patient might perceive the clinician as attempting to mislead or manipulate him. A therapeutic alliance could require patience on the part of the clinician, creativity,1 and abandoning attempts at rational “therapeutic” persuasion. The severity of symptoms determines the approach.

In this article, we review the nature of paranoia and the continuum of syndromes to which it is a central feature, as well as treatment approaches.

Categorization and etiology

Until recently, clinicians considered “paranoid” to be a subtype of schizophrenia (Box2-7); in DSM-5 the limited diagnostic stability and reliability of the categorization rendered the distinction obsolete.8 There are several levels of severity of paranoia; this thought process can present in simple variations of normal fears and concerns or in severe forms, with highly organized delusional systems.

The etiology of paranoia is not clear. Over the years, it has been attributed to defense mechanisms of the ego, habitual fears from repetitive exposure, or irregular activity of the amygdala. It is possible that various types of paranoia could have different causes. Functional MRIs indicate that the amygdala is involved in anxiety and threat perception in both primates and humans.9

Rational fear vs paranoia

Under the right circumstances, anyone could sense that he (she) is being threatened. Such feelings are normal in occupied countries and nations at war, and are not pathologic in such contexts. Anxiety about potential danger and harassment under truly oppressive circumstances might be biologically ingrained and have value for survival. It is important to employ cultural sensitivity when distinguishing pathological and nonpathological paranoia because some immigrant populations might have increased prevalence rates but without a true mental illness.10

Perhaps the key to separating realistic fear from paranoia is the recognition of whether the environment is truly safe or hostile; sometimes this is not initially evident to the clinician. The first author (J.A.W.) experienced this when discovering that a patient who was thought to be paranoid was indeed being stalked by another patient.

Rapid social change makes sweeping explanations about the range of threats experienced by any one person of limited value. Persons living with serious and persistent mental illness experience stigma—harassment, abuse, disgrace—and, similar to victims of repeated sexual abuse and other violence, are not necessarily unreasonable in their inner experience of omnipresent threat. In addition, advances in surveillance technology, as well as the media proliferation of depictions of vulnerability and threat, can plant generalized doubt of historically trusted individuals and systems. Under conditions of severe social discrimination or life under a totalitarian regime, constant fear for safety and worry about the intentions of others is reasonable. We must remember that during the Cold War many people in Eastern Europe had legitimate concerns that their phones were tapped. There are still many places in the world where the fear of government or of one’s neighbors exists.

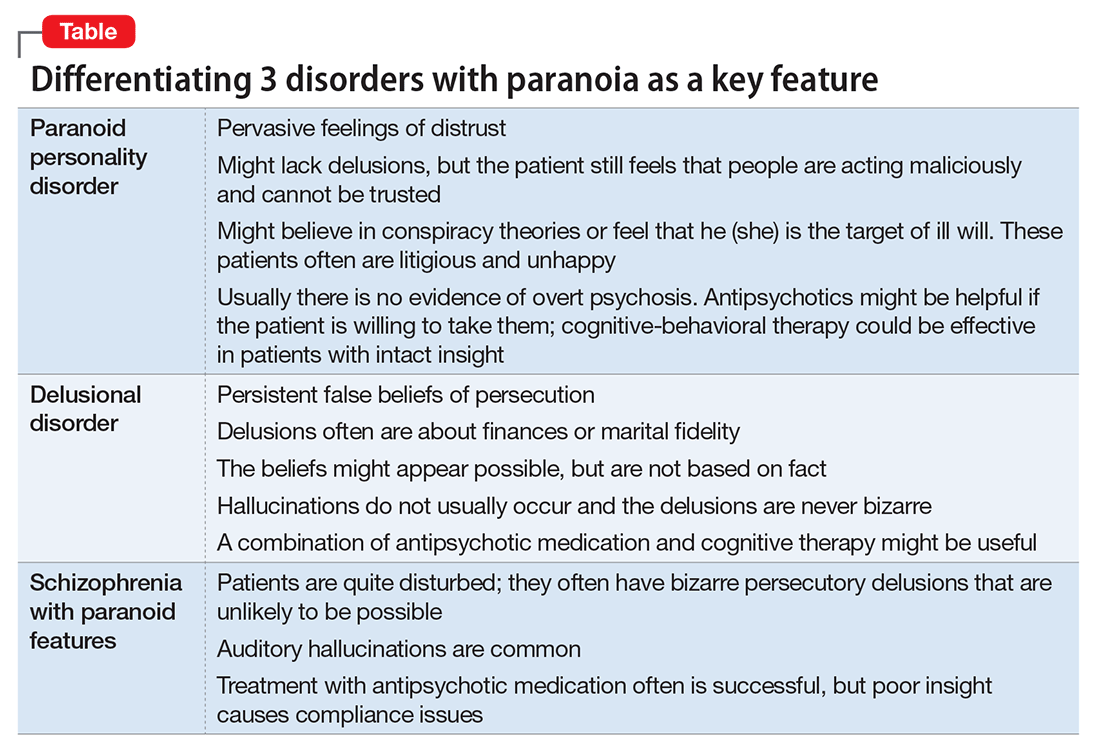

In a case of vague paranoia, clinicians must take care in diagnosis and recommending involuntary hospitalization because psychiatric treatment can lead to scapegoating persons for behavior that is not pathological, but merely socially undesirable.11Symptoms of paranoia can take more pathological directions. These 3 psychiatric conditions are:- paranoid personality disorder

- delusional disorder

- paranoia in schizophrenia (Table).

Paranoid personality disorder

The nature of any personality disorder is a long-standing psychological and behavioral pattern that differs significantly from the expectations of one’s culture. Such beliefs and behaviors typically are pervasive across most aspects of the individual’s interactions, and these enduring patterns of personality usually are evident by adolescence or young adulthood. Paranoid personality disorder is marked by pervasive distrust of others. Typical features include:

- suspicion about other people’s motives

- sensitivity to criticism

- keeping grudges against alleged offenders.8

The patient must have 4 of the following symptoms to confirm the diagnosis:

- suspicion of others and their motives

- reluctance to confide in others, due to lack of trust

- recurrent doubts about the fidelity of a significant other

- preoccupation with doubt regarding trusting others

- seeing threatening meanings behind benign remarks or events

- perception of attacks upon one’s character or reputation

- bears persistent grudges.8