A customer shops at Pete’s Fruit Market in Milwaukee. Children's Wisconsin has a pilot program at its Midtown Clinic in which a physician, or other clinician, can give struggling patients a voucher for food at the grocery store. Angela Peterson/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

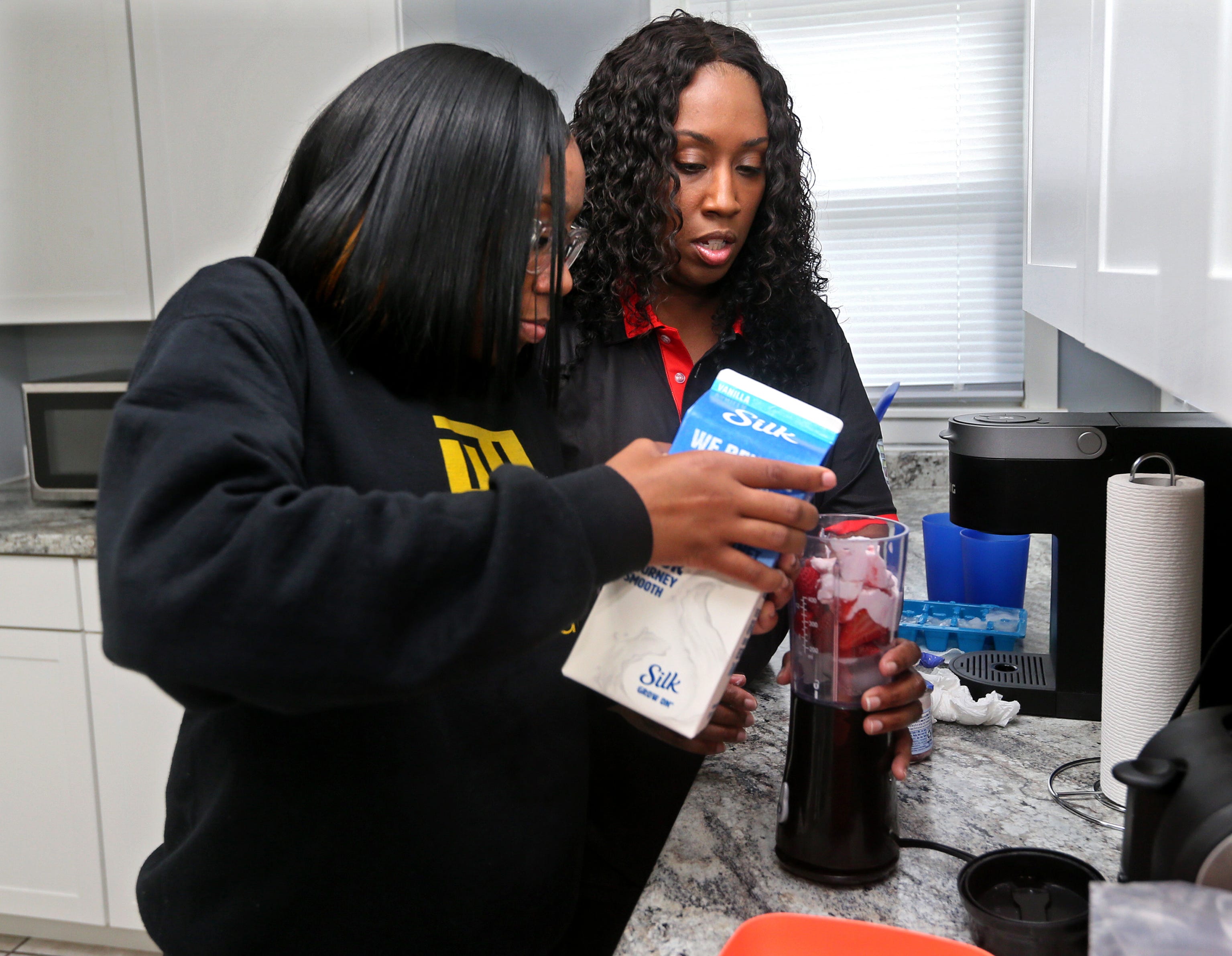

Shelly Greer, diagnosed with diabetes in late 2017 at the age of 38, was struggling to manage the disease when a physician referred her to a new program at Ascension Wisconsin.

“I really needed it at the time,” Greer said.

Her HbA1c, a blood sugar measurement critical for diabetics, was at 10; below 8 is the threshold for diabetes under control.

Ascension Wisconsin started the program — called Under 8 — in 2020, focusing on patients who live in the low-income neighborhoods near its Ascension SE Wisconsin-St. Joseph campus on the city's northside.

The 12-week program provides five prepared healthy meals — designed for people with diabetes — each week from UpStart Kitchen, a restaurant incubator in Milwaukee's Sherman Park neighborhood. The program also provides grocery bags of food healthy for diabetics, and holds weekly meetings that offer counselling on nutrition, lifestyle and medication adherence.

Over the duration of the program, Greer's HbA1c fell from 10 to 6.3.

The program is an example of how to improve health by going outside the four walls of a clinic and meeting people where they live, said Nancy Leahy, a nurse practitioner with Ascension Wisconsin.

“We do it in a community setting, where people are a little more comfortable than meeting in a hospital or a clinic," she said.

It also is one of hundreds of initiatives — most of them small for now — started by health systems nationwide that move beyond doctor visits in clinical settings and instead address underlying social and economic conditions that affect health, particularly among poor people.

Those conditions — what are known as the social determinants, or drivers, of health — can be more important than access to the best doctors and medicines in influencing a person's overall health. They include food, housing, education, employment, neighborhoods, and the support of family and friends.

Putting more resources toward addressing them not only could improve lives, it could save money.

Adequate and stable housing often is considered the foundation of good health. But access to healthy and appropriate food can be as important, particularly in managing chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart failure. And those conditions are more common among people who have low incomes.

Some initiatives by health systems and, increasingly, health insurers focus on finding new ways to help people with those conditions to eat healthier. Some center on lessening food insecurity — the uncertain access to adequate, quality food. Some do both.

There are hurdles to overcome.

Healthy food can be more expensive, and the amount of money someone on a tight budget spends on housing can limit what's left for food.

Lower-income neighborhoods may be so-called food deserts, where corner convenience stores with limited offerings have taken the place of full-fledged supermarkets. For someone without a car, a trip to a supermarket can become a trek that involves several buses, possibly young children in tow, and then hauling back bags of groceries.

"Fundamentally this gets down to insufficient resources that people need to maintain health, and food insecurity is just one manifestation of that,” said Seth Berkowitz, a physician and professor of general medicine and clinical epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Education and health literacy — understanding what makes up a healthy diet and how to achieve it — also have a role. People who are skeptical of the prevalence of food insecurity note that many poor people are overweight or obese. What's lost is that some, without the knowledge or the ability to get good food, may be getting by on calorie-rich processed foods and snacks.

The cost of food insecurity

The impact of food insecurity on health is not new.

For adults, it is associated with diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, obesity, chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, depression and other medical conditions, according to the Food Research & Action Center.

Food insecurity added an estimated $51.8 billion a year to the health care costs for adults, according to a 2019 study done by Berkowitz and his co-authors.

That included an estimated $687 million in additional health care costs in Wisconsin.

The study found that health care costs for adults who were food insecure was $1,073 to $2,595 a year higher than costs for adults who had adequate food.

The study did not find a significant increase in costs for children.

But food insecurity is associated with an array of poor health outcomes for children, from more frequent colds and stomach aches to behavioral health conditions, according to the Food Research & Action Center.

“After multiple risk factors are considered, children who live in households that are food insecure, even at the lowest levels, are likely to be sick more often, recover from illness more slowly, and be hospitalized more frequently,” the American Academy of Pediatrics said in a policy statement titled Promoting Food Security for All Children. “Lack of adequate, healthy food can impair a child’s ability to concentrate and perform well in school and is linked to higher levels of behavioral and emotional problems from preschool through adolescence.”

For adults, much of the increased cost for adults came from more hospital stays and emergency department visits.

Here’s one example: A study done in California found a 27% increase in hospital admissions for people with diabetes who have low incomes in the last week of the month compared with the first week. There was no change for people with higher incomes.

The likely reason is that people with low incomes had exhausted their food benefits and had less access to the foods essential to managing the disease at the end of the month.

The increase overall actually was higher. The study looked at just hospital admissions and did not include increased visits to clinics or emergency departments.

Low-interest loans, vouchers for food

Nationally, initiatives by health systems have included providing financial support, such as low-interest loans for supermarkets to open in a low-income neighborhood. Some are experimenting with providing medically tailored meals to people with chronic diseases.

The initiatives supplement and build on the work done for decades by organizations throughout the country, such as the Hunger Task Force in Milwaukee, to lessen food insecurity and encourage healthy diets.

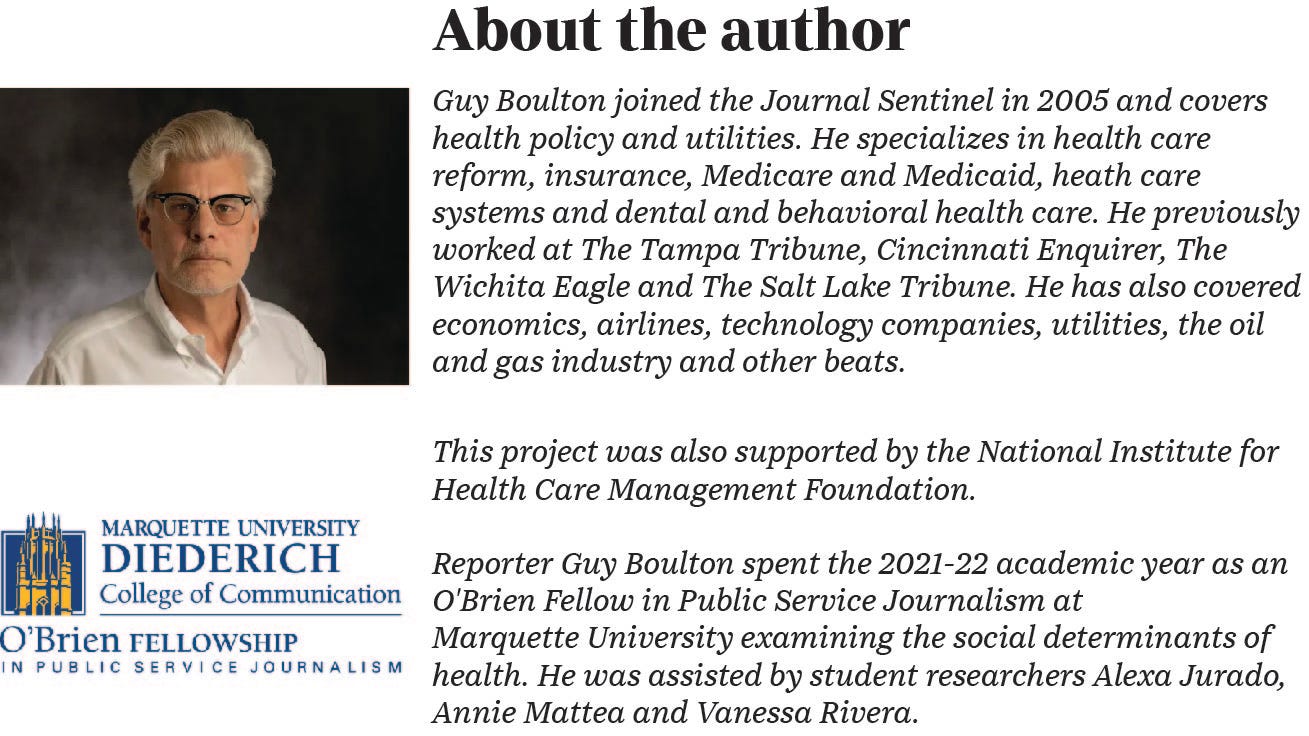

Chorus Community Health Plans, formerly Children’s Community Health Plan, for example, has a pilot program — Fresh Food Rx — that enables physicians and other clinicians at its Midtown Clinic to give vouchers for Pete’s Fruit Market to people who have been screened for food insecurity.

The grocer offers items such as its popular value baskets that contain a mix of vegetables and fruits, said Sam Cunningham, manager of the store at 2323 N. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

“Healthy eating means a long-lasting life,” Cunningham said.

Again, there are hurdles.

Children can be picky eaters, said Lisa Zetley, a pediatrician at the Midtown Clinic. Families with low incomes often buy things that won’t spoil. Some people don't know how to cook different vegetables.

Chorus Community Health Plans, an affiliate of Children’s Wisconsin, offers everyone in its health plans free access to the Foodsmart app.

More than 5,400 people in its health plans have signed up for the app. One feature provides access to a registered dietrician, and 3,145 people in the health plans have made use of that feature more than 5,500 times so far.

The app also provides healthy recipes that appeal to children. It then turns the recipes into a shopping list — and shows which supermarkets have the lowest prices for the ingredients.

The idea is to offer personalized, culturally relevant recipes that are affordable and support lasting changes to eating behavior, said Mark Rakowski, president of Chorus Community Health Plans

"This is literally the first solution that resonates with all of our providers as they look to support the patients and families that are food insecure, or who are looking for support to eat healthier," he said.

Cutting or skipping meals

An estimated 33.8 million people — living in more than one in 10 households — were food insecure in 2021, according the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

This means they reduced the quality or variety of what they ate because of lack of money or other resources at some point during the year. It doesn’t happen regularly. But it happened on average in seven months of the year.

These figures require some parsing.

They include 8.6 million adults — and 521,000 children — who live in 5.1 million households with very low food security.

This means that one or more people in the household — usually an adult — ate less or went without food at times during the year because they had insufficient money or other resources.

In more than 80% of those households, an adult cut or skipped a meal because of a lack of food in three or more months out of the year.

In Wisconsin, an average of 246,000 households were food insecure and 77,000 had very low food security from 2019 through 2021, according to the USDA.

Without question, food insecurity would be more widespread and severe without federal food programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, or WIC; and the National School Lunch Program.

But those programs only go so far: 56% of the households that reported being food insecure did so even though they participated in one or more of those programs, according to the USDA.

The number of food pantries in southeastern Wisconsin — more than 100, including ones open only a few hours a week — suggests the extent of food insecurity. They have become an integral part of the country’s safety net.

To advocates, that’s less than ideal.

“Food pantries are things we should be putting out of business,” said Sherrie Tussler, executive director of the Hunger Task Force.

Feeding more than 42 million

The largest and most important of the federal programs is SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

The program helps feed more than 42 million Americans — roughly 1 in 8 — each month. Two-thirds of those participating in the program are children, over 65 or people with disabilities.

“SNAP has become the key safety net program for low-income families,” said Choe East, an economist at the University of Colorado-Denver who has studied the program.

Eligibility is based on a complex formula that includes an array of deductions for living expenses. Individuals and families are expected to spend 30% of their income on food after those deductions.

The benefits are available only to U.S. citizens and limited groups of legal immigrants. Undocumented, or illegal, immigrants are not eligible.

Workers on strike and most college students are not eligible. And unemployed adults 18 to 50 without children and who are not disabled are eligible for only three months every three years.

Advocates have long contended that SNAP benefits are too low — Tussler said the benefit is based on a starvation diet created in the 1960s.

On Oct. 1 last year, the federal government increased the benefit by 21%, or an average of $36.24 a month per person, after the USDA re-evaluated the cost of a nutritious, practical diet.

Evidence consistently shows that the benefit was too low to provide for a realistic healthy diet, the USDA said.

“It’s an investment in our nation’s health, economy, and security,” Tom Vilsack, the Secretary of Agriculture, said in a news release. “Ensuring low-income families have access to a healthy diet helps prevent disease, supports children in the classroom, reduces health care costs, and more.

Studies support that.

One study found that access to food stamps before birth and in early childhood leads to a significant reduction in the incidence of obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes in adulthood.

Studies also have shown that the program improves children’s reading and math skills and increases their chances of graduating from high school.

Critics of the program contend that it could have more incentives to encourage people to buy the right foods. Some studies have noted the amount spent on soda and frozen desserts.

“Americans across the economic spectrum don’t have the best diets,” said Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, a professor of education and social policy at Northwestern University.

In general, people want a healthy diet when they have more resources, she said. But she acknowledged that encouraging people to eat healthier is complicated.

“I wouldn’t want to pretend that there is a simple answer,” said Schanzenbach, a national expert on the SNAP program and co-author of an important study on its long-term benefits.

The goal is not to help people afford more food, but to help them afford healthier food.

The recent increase in SNAP benefits — which was based partly on a diet that includes more fish, and red and orange vegetables — was designed with that in mind.

'You need that extra encouragement'

Many of the initiatives by health systems focus as much on encouraging people to eat healthy as on food insecurity.

Ascension Wisconsin’s Under 8 program, for instance, changed the way Greer eats. She no longer eats fried foods and now eats less meat and more fruit and vegetables. And she learned about healthy alternatives to snacks, which are important in maintaining the right level of blood sugar.

“There were some nuts that I didn’t know we could have,” Greer said.

The weekly educational sessions are held at Ebenezer Ministry & Family Worship Center. The program also has an arrangement with Lyft for people who need transportation.

So far, 27 people referred by their physicians have participated in the program and their HbA1c levels have dropped by an average of 1.6 points.

“We notice that just small changes in their diet can actually improve their diabetes,” said Leahy, the nurse practitioner with Ascension Wisconsin.

The prepared meals and grocery bags of food, though, may be secondary in the program’s effectiveness.

Being with other people who had diabetes was the best part of the program, Greer said.

“You feel like you are alone in this thing,” she said. “It was so overwhelming.”

The people in the program knew what it was like to have diabetes and encouraged each other. “You could just be yourself and you were amongst friends,” she said.

Greer plans to volunteer to help future groups in the program.

“I know how it feels,” she said. “Sometimes you need that extra encouragement.”

Thousands of dollars saved

The Ascension Wisconsin program is similar but somewhat less structured than one of the most promising interventions that link food and health — what are known as medically tailored meals.

Geisinger Health, a health system in central Pennsylvania, has drawn national attention for its Fresh Food Farmacy program for people with uncontrolled diabetes who were food insecure.

People in the program received enough food to prepare 10 healthy meals for their whole family, plus weekly sessions on managing diabetes. The program also provided transportation to the sessions when needed.

Medical expenses fell between $16,000 and $24,000 for each person in the initial program — though the initial rollout included particularly complex and high-cost patients, according to an article in the Harvard Business Review.

The improvement in their health was equally impressive.

Within 12 months, the participant’s HbA1c levels dropped more than two points, from an average of 9.6 before the program to 7.5.

Each one-point drop results in an estimated 20% drop in the chance of death and complications, such as blindness and kidney failure from diabetes, according to the article. It also is estimated to save $8,000 to $12,000 in health care costs.

All this took work, involving a team that included a program coordinator, nurse, primary care physician, registered dietitian, pharmacist, health coach, community health assistant and administrative staff.

Most of the program’s cost — about $2,200 per participant in 2017 — was in staff time, not in the cost of food.

The program suggests the potential improvement in health — and potential cost savings — in treating diabetes by focusing on food and intensive coaching of patients.

Other programs also have demonstrated success in using food to treat disease.

Community Servings in Boston was a pioneer. It started a program 1990 with AIDS activists, faith groups and community organizations through the leadership of the American Jewish Congress to provide home-delivered meals to people with HIV/AIDs.

The program now provides 10 meals and snacks, such as fresh fruit, homemade rolls and apple sauce, throughout Massachusetts to people with certain chronic diseases.

It also contracts with health plans to offer the meals as a benefit to help keep people stay out of the hospital.

The program lowered the health care costs of the participants by an average of 16%, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA.

The savings came from fewer hospital admissions, visits to emergency departments, ambulance transfers and stays in rehabilitation hospitals.

Massachusetts’ Medicaid program now pays for medically tailored meals. North Carolina, California and New York also have programs or pilot programs that do the same.

“It's vital for people's health and well-being,” said Jean Terranova, director of food and health policy at Community Servings.

Community Servings is one of the founding members of the Food is Medicine Coalition that is working to make medically tailored meals available nationwide and lobbying to have Medicare and state Medicaid programs to cover them the same way they cover prescription drugs and other treatments.

Food For Health, a nonprofit organization spun out from the Dohmen Company Foundation in Milwaukee, is a member of the coalition and hopes to make medically tailored meals available throughout Wisconsin.

Building a body of research

Medically tailored meals are the intervention that has been most studied. But researchers still are trying to figure out what works best.

The Medical College of Wisconsin, for instance, is doing studies that look at the most effective ways to encourage people with chronic diseases to maintain a healthy diet, including one in which it is working with the Hunger Task Force in Milwaukee.

The studies, which are funded by the National Institutes of Health, are designed to build on the smaller studies that have been done so far.

“If we provide food as part of medical care, we actually don't know if that will change your health outcome,” said Rebekah J. Walker, a professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

The studies that have been done so far, though, are encouraging.

“A lot of the work that we have suggests where you should go,” Walker said.

Not every initiative will improve health or lower health care costs. And some are likely to fail.

But momentum is building, as physicians, health systems and health insurers increasingly see food as an integral part of health care.

“It comes down to using the right type of intervention in the right circumstances,” Berkowitz said.

Annie Mattea contributed to this report while attending Marquette University and working as a research assistant to O'Brien Fellow Guy Boulton.