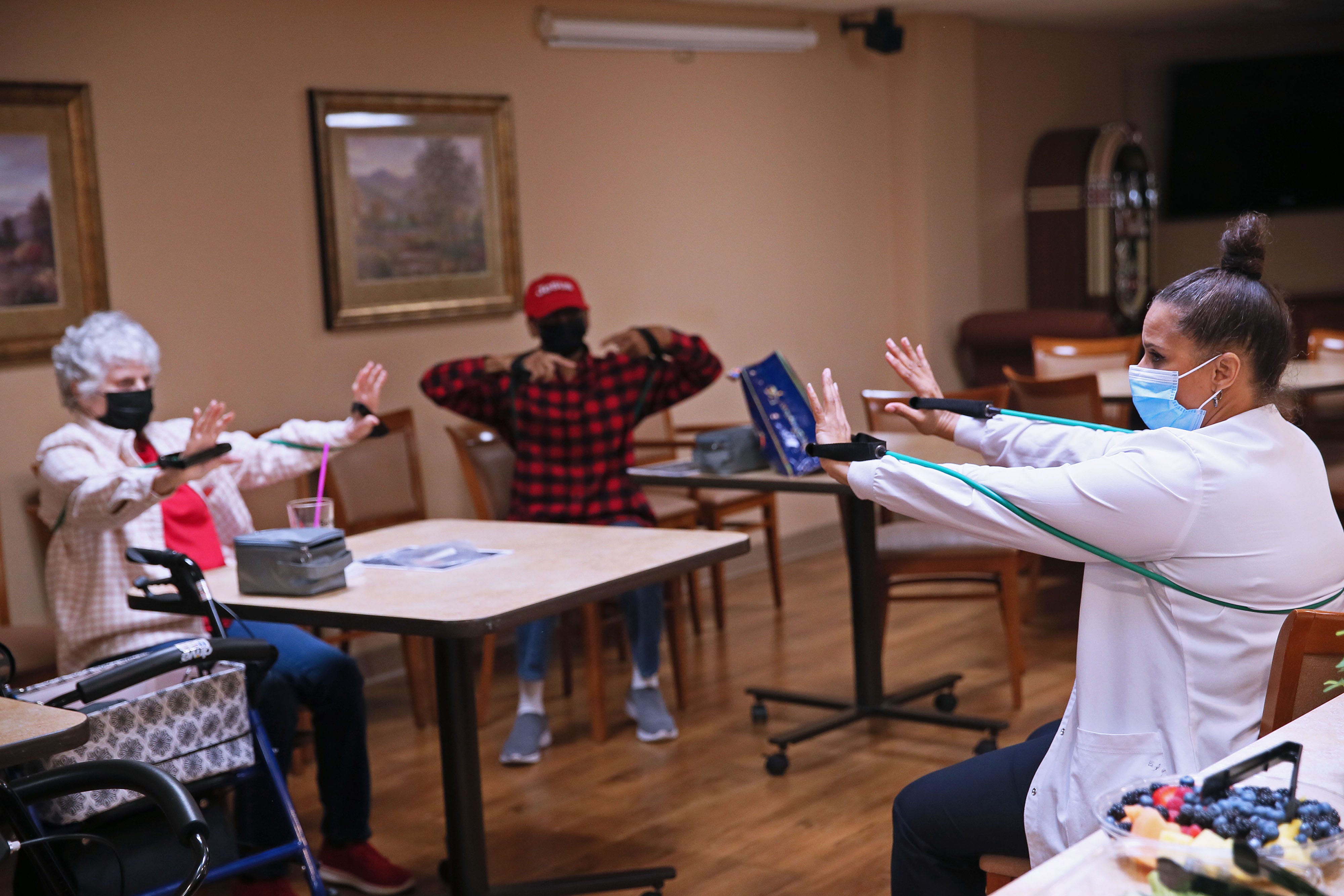

Tya Bryson does a cartwheel while Lailah Montgomery watches on Wagner Street in Columbus, Ohio, facing north toward Nationwide Children’s Hospital. The hospital and its partners have pumped millions into renovating and building homes in the neighborhood through the Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families program. Kyle Robertson/The Columbus Dispatch

In his first five months enrolled in Children’s Community Health Plan, Patrick Sweat visited emergency departments 44 times and was hospitalized 11 times.

His medical care was costing about $11,000 a month.

Then the health plan tracked him down — he didn’t have a phone, much less an address — and set him up with an apartment.

Sweat’s medical bills fell to about $300 a month.

Paying for his apartment not only saved the health plan money, but also improved his life.

Sweat had been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis as a child, and part of his colon was removed in 2010. Without a place to live, he couldn’t easily get medical supplies for his colostomy bag, so he would head to emergency departments.

“Obviously, when he was homeless, they couldn’t be delivered to his home,” said Mark Rakowski, president of Children's Community Health Plan, which was renamed Chorus Community Health Plans this month.

Sweat is an example of one of the disconnects in the U.S. health care system.

We will spend tens of thousands of dollars on health care for people, but not ensure they have adequate housing. Yet stable and adequate housing often can do more to improve someone’s health than the best medical care — and, in some cases, at lower cost.

“We can’t expect people to take great care of their health if they don’t have a roof over their head,” said Linda Schauf, a nurse and manager of a prenatal care program at Chorus Community Health Plans, an affiliate of Children’s Wisconsin.

Food, jobs, education, transportation, safe neighborhoods and social networks — the social determinants, or drivers, of health — can have as much or more impact on a person as access to health care.

Housing intersects with all of those.

“Housing really is the foundation for health and well-being,” said Craig Pollack, a physician and professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Lessening food insecurity

Health systems and insurers increasingly realize they will be unable to improve the health of some patients without addressing housing.

When Children’s Community Health Plan asked recipients what it could do to lessen food insecurity, they said provide stable housing.

“That is the number one, number two and number three worry for families,” Rakowski said.

Yet only one out of ever four people eligible for rental assistance actually receives it because of limited funding.

Adjusting for inflation, the United States spent almost three times more on housing assistance programs in the 1970s than today, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

That’s despite the increase in the percentage of people who work in low-wage jobs and struggle to make their monthly rent because of the changes in the economy over the past four decades.

Damage spans generations

The damage done by inadequate or inconsistent housing spans generations.

Studies have shown that for people who are chronically homeless and for women who are pregnant or who have a newborn child, the cost of providing housing can be offset by the savings in health care costs.

Providing housing to those two groups is where the potential savings are greatest and where the evidence is strongest.

But the lack of affordable housing affects almost everyone who is poor.

A study by Children’s HealthWatch in Boston estimated that housing instability among families with young children will result in $111 billion in avoidable health care and special education costs nationwide over a 10-year period.

The study estimated that 10.2 million children and their families in 2016 could have avoided preventable health conditions had they been in safe and stable housing.

Physicians, advocates and others working to draw attention to the disconnect regularly state that “housing is health.”

Lead poisoning — which can cause permanent brain damage in young children — is the most obvious example of the effect of substandard housing. Another is exposure to mold, dust mites, cockroaches, mice and other triggers for children and adults with asthma.

Moving from place to place, particularly for children, also has long-term consequences. Young children whose families move two or more times in a year are at risk of poor health and developmental outcomes, according to multiple studies.

Older children who have moved frequently throughout childhood are more likely to develop behavioral health problems. Housing instability can increase the risk of teen pregnancy, early drug use and depression, according to an overview of the research by Health Affairs, a policy journal.

“Investing in housing for children is a way of investing in prevention,” said Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, a professor of human development and social policy at Brandeis University.

Further, what families spend on rent affects how much money they have for food, transportation and activities for their children. It also can influence access to jobs and good schools. Those, too, have been shown to influence health.

“Children have poorer educational outcomes,” said Diane Yentel, president and CEO of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “Parents have more difficulty in obtaining and retaining jobs. And all of this costs us.”

The need to feel engaged, connected

This is why housing is considered the foundation for health and well-being.

“Without stable, affordable housing, people on limited incomes will never get to a stable place,” said Mark Angelini, president of Mercy Housing Lakefront.

The nonprofit organization, founded by the Sisters of Mercy, provides low-income housing and other services in Milwaukee, Kenosha and Racine, as well as in Illinois and Indiana. Its operations include housing for families, and people over 65, as well as permanent supportive housing for people who are chronically homeless.

“We work to help people get economically stable,” he added. “We help people get to a better job. We spend a lot of time dealing with individuals and families that have suffered from the isolation inherent in poverty, to come up with ways (for them) to feel engaged and connected.”

Angelini talks about what can be accomplished when you start with allowing people to live with dignity in safe, stable, healthy housing.

“And that's critical to not only maintaining people's health,” he said. “It's critical to kids achieving in education and being able to move forward.”

In Sweat’s case, Children’s Community Health Plan initially paid for transitional housing. He then got a housing voucher through the Milwaukee County Housing Division’s Housing First program.

Sweat’s studio apartment on Milwaukee’s south side cost $595 a month including utilities. It enabled him to begin making progress in other areas of his life.

Through the health plan, he began working with a case manager and started regularly attending his appointments for medical and behavioral health care. He even began working to connect other people who were homeless with resources.

“It’s actually given me a lot more serenity,” he said in his apartment. “I can sleep with two eyes closed.”

Sweat is an example of how homelessness affects health in another way.

The average life expectancy among people who are homeless is between 42 and 52 years old.

Sweat died suddenly in the summer of 2020. He was in his mid-forties.

Dictating their own treatment

The Housing First program, started in 2015 and based on a national model, provides permanent housing with no pre-conditions, such as requiring participation in specific programs or employment. It instead offers optional services, such as treatment for substance abuse.

“We really try to let our clients dictate their own level of service,” said James Mathy, administrator of the Milwaukee County Housing Division.

It can start by simply reconnecting with family, he said. With time, people often are ready to accept other services. And the optional services are one of the reasons that the program has been successful.

The premise is that people need basic necessities, such as food and a place to live, before they can begin focusing on other changes in their lives, such as getting a job or seeking treatment for substance abuse or behavioral health conditions.

“Asking people to do all those things while they were living outdoors on the street was just highly problematic and it wasn't practical,” said Eric Collins-Dyke, assistant administrator of supportive housing and homeless services for the Milwaukee County Housing Division.

The Housing First program costs $2 million to $3 million a year. It has reduced Wisconsin’s spending on Medicaid programs by an estimate $2.1 million a year, and has reduced Milwaukee County’s cost of providing behavioral health care by $715,000 a year, according to a brief by the La Follette School of Public Affairs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

In other words, it pays for itself.

Most people are unaware of potential savings, said Kaelin Deprez, a manager at the Milwaukee County Behavioral Health Division. “That’s where the missing piece of the story is.”

Lack of affordable housing

The Housing First program gives priority to people who are chronically homeless — those who have been homeless for one year, or had four episodes of homelessness in the past three years equaling 365 days — and who have physical and behavioral health conditions.

They are the most tangible example of how housing affects health.

But the same holds for a much larger group of people: those who live with the constant stress of making their monthly rent and the risk of eviction and homelessness.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has released a report, based on the American Housing Survey, every two years since 1973 on households with worst-case housing.

That’s defined as households with incomes at or below 50 percent of area median income that do not receive government housing assistance and that pay more than half of their income toward rent, live in severely inadequate conditions, or both. (The median household income for Milwaukee — meaning half of the households had incomes above and half below — was estimated at $43,125 in 2020 by the U.S. Census Bureau.)

The report found that 7.77 million households — or almost one in 16 — paid more than half of their income for rent in 2019. That includes 2.27 million households with children and 2.24 million households headed by someone 62 years old or older.

The lack of affordable housing — widely considered a national crisis — can be seen in Milwaukee County.

More than half — 50.6% — of the households in Milwaukee County rented their homes in 2016, according to a 2018 report by the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

Roughly half of the households that rent paid more than 30% of their income on housing. And roughly one in four of those who rent paid at least 50% of their income on housing.

The Policy Forum estimated that for households with incomes of less than $25,000 a year — roughly the income of someone who makes $12 an hour — there was a shortage of 63,000 affordable housing units in Milwaukee County in 2016.

In all likelihood, the problem has gotten worse.

What vouchers can do

The federal Housing Choice Voucher program is the most common form of assistance.

It limits what a person or family pays for housing and utilities to 30% of their income. That is the top end of what is considered “affordable” housing for individuals or a family in the United States.

Getting a housing voucher — given that only one in four eligible individuals or families receive them — is like winning the lottery.

So is living at a place like GreenTree Apartments in Milwaukee. The roughly 700 people who live at GreenTree receive housing vouchers.

The waiting list for a one-bedroom apartment is three to four years, said Vicki Davidson, program coordinator for the complex.

GreenTree regularly gets inquiries from people who are living in shelters, who are about to be evicted, who have a bad landlord or who are in an abusive relationship.

The apartment complex, which has 328 units, is one of four in Milwaukee and two in Madison overseen by Housing Ministries of American Baptists in Wisconsin.

Lillie Curry said that friends tell her that she is lucky to be living at GreenTree. Curry's daughter died of a brain tumor and she is raising three of her grandchildren.

The oldest of the three, Lakendra Curry, is studying accounting at Mount Mary University. She also works part-time in the complex's summer tutoring program. The demanding program, staffed in large part by teachers on summer break, focuses on reading, math and science.

It is one of several education programs at the complex. GreenTree has a Head Start program on site. It helps adults earn their GED, and offers courses on using computers. Its computer lab is open to high school and college students.

Rev. Carmen Porco, who oversees the Housing Ministries complexes, said the goal is to using housing to initiate social change — "giving people the ability to design their own destiny."

But he, too, lamented the limited number of vouchers and noted the need for more affordable housing.

The federal government allocated $27.4 billion for the voucher program in the current fiscal year, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a left-leaning research organization.

It’s a stark contrast to health care spending.

The United States spent an estimated $122.4 billion to $146.9 billion just on low-back and neck pain in 2016, according to a study published in 2020 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA. The cost is borne by employers, health insurers and government health programs.

That means the United States spends roughly five times more to treat low-back and neck pain than it spends on the primary program to provide affordable housing to low-income individuals and families.

Early steps in Milwaukee

Some health systems have been at the forefront of investing in housing as part of their initiatives to address the underlying social and economic conditions that affect health.

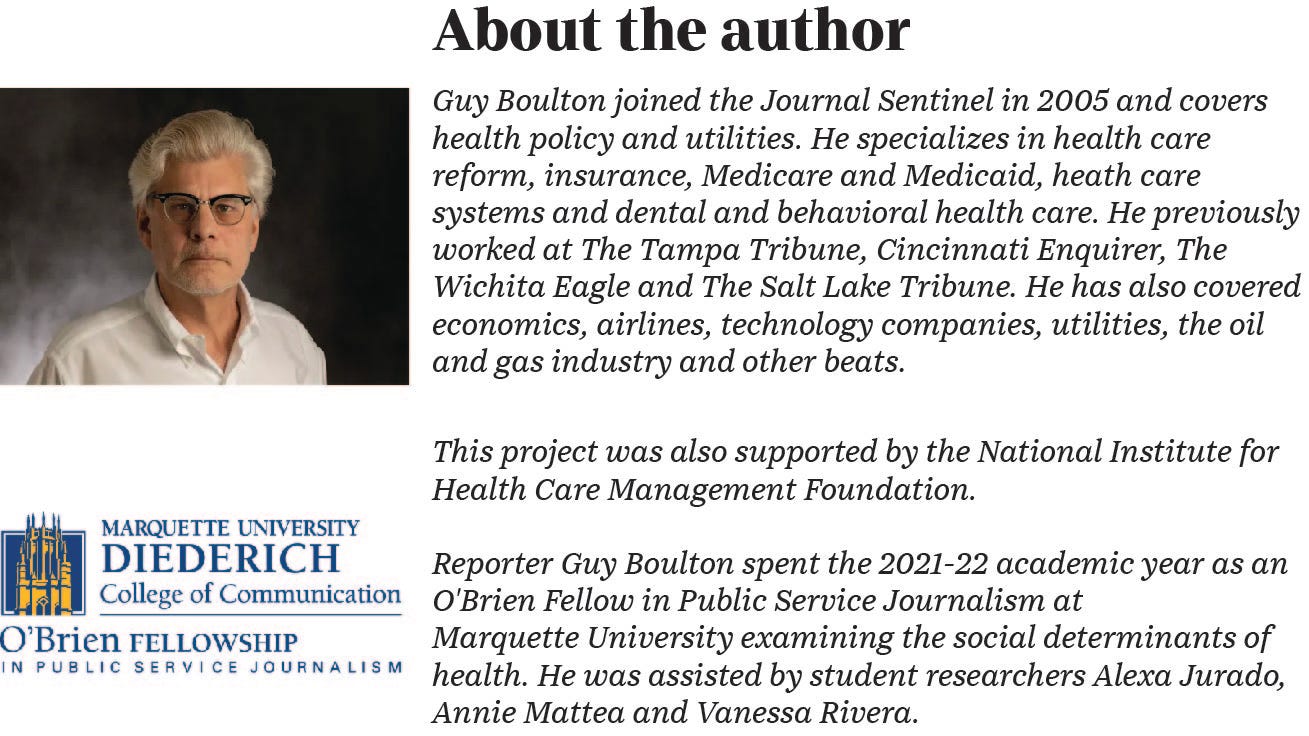

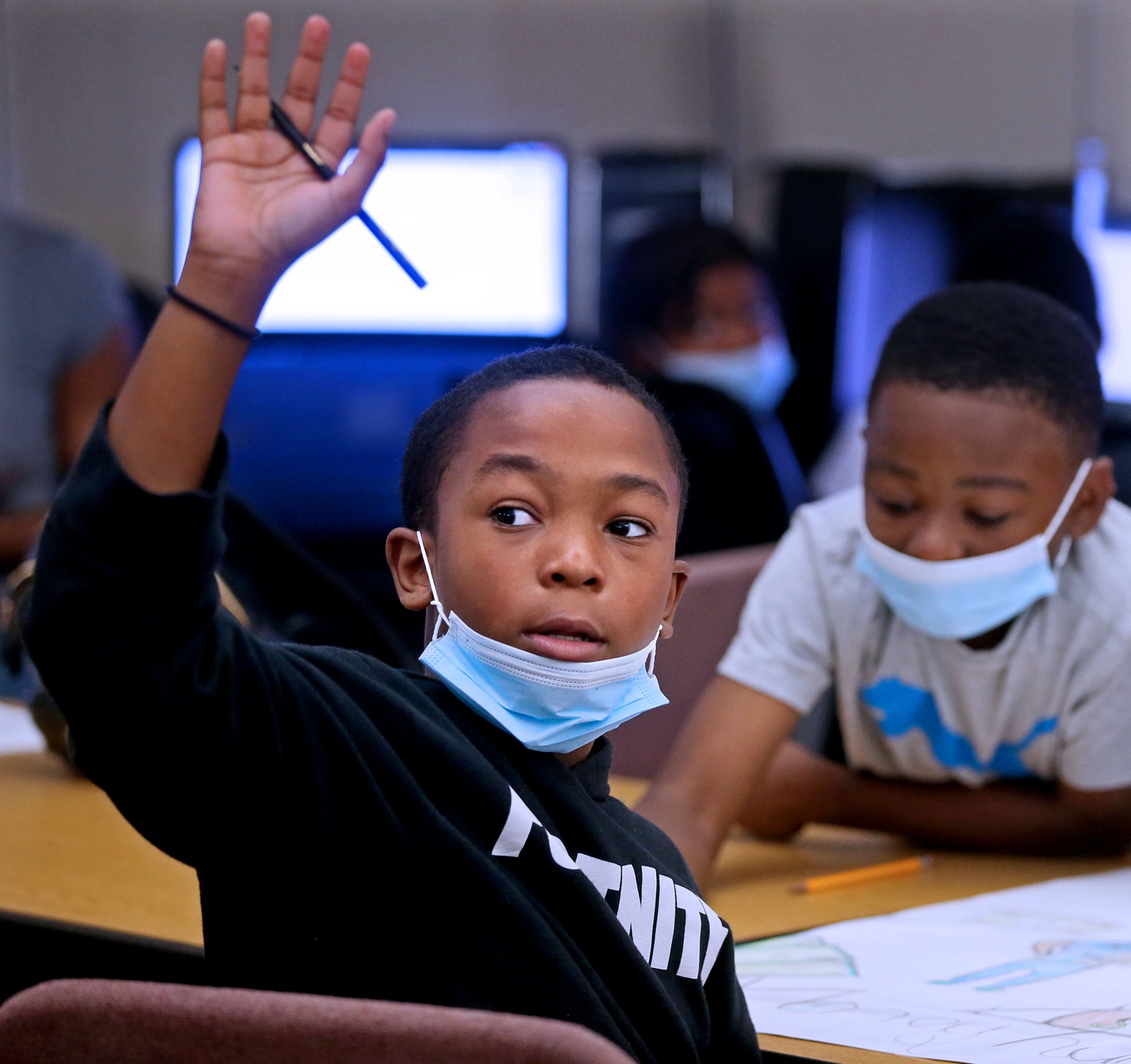

Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, began its Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families initiative in 2008. The initiative has renovated, built or repaired a little more than 500 housing units, and has plans to do the same for at least an additional 500 units over the next 5 years.

The initiative — which includes faith-based organizations, community development organizations, workforce development programs, nonprofits and public schools — also focuses on education, health and wellness, safe neighborhoods and workforce development.

More than $56 million has been invested in the neighborhoods to date through a combination of equity investments and loans from the health system, and philanthropy, said Katelyn Scott, a spokeswoman for the health system.

Elsewhere, CommonSpirit Health, a Catholic health system with hospitals in 21 states, has long provided loans at below-market rates and loan guarantees to promote access to jobs, housing, food, education and health care in low-income communities through its Community Investment Program.

As of March 31, the program had $112 million in outstanding loans and $5 million in loan guarantees, with $36 million in loans and guarantees yet to be deployed.

In April, Kaiser Permanente, which operates in eight states and the District of Columbia, announced that it would invest $400 million in affordable housing, doubling a $200 million commitment made in 2018 to its social impact investment fund. The health system expects to create or preserve 30,000 units of affordable housing by 2030.

For now, none of the health systems in Milwaukee has plans to invest in low-income housing. However, some health insurers have taken first steps.

Chorus Community Health Plans worked with the Milwaukee County Housing Division to pay first for 10 and now about 17 apartments for people in its health plans who have, or are at risk of, high health care costs.

UnitedHealthcare Community Plan of Wisconsin and Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield — health insurers who also manage the care of people covered by BadgerCare Plus — have similar initiatives.

In 2018, UnitedHealthcare worked with the Milwaukee County Housing Division to begin paying for the housing costs, including utilities, for 11 people in its health plan covered by BadgerCare Plus.

In the first six months, the 11 people spent six nights in a hospital, compared with 42 nights in the six months before getting housing. They visited hospital emergency departments 21 times, compared with 149 times in the six months before getting housing.

The cost of providing the housing initially was about $700 a month, or $8,400 a year. Some of the people had medical bills that topped $100,000 a year because of frequent emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

A rebalancing is in order

Milwaukee County and the City of Milwaukee — working with private developers, including nonprofit organizations — have made increasing the supply of affordable housing a priority.

Rakowski, of what is now Chorus Community Health Plans, describes the staff of the Milwaukee County Housing Division as “unsung heroes.”

Dozens of housing projects have been completed in the past decade. And the American Rescue Plan Act has provided money for additional projects.

But many of the projects can set aside only a set number of units for people with low incomes — typically incomes 50% to 60% of the median income — for the economics to work.

One of the dreams of the staff of the Milwaukee County Housing Division, Collins-Dyke said, is that doctors one day would be able to write prescriptions for housing. Realizing that dream would require a massive increase in spending on vouchers and other rental assistance.

Nationally, 15 million households — almost one in eight — need help to afford housing, according to estimates by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Spending would need to double to help all of them, said Sonya Acosta, a senior policy analyst on housing at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

That seems unrealistic — fiscally and politically — given the federal budget deficits and given the staunch opposition by many people to increased spending on social programs. But put the $27.4 billion that the country spends on housing vouchers in context with the $4.1 trillion it spends on health care.

More and more, physicians, health advocates, and even health systems and health insurers, are suggesting a rebalancing is in order.

“We are spending a lot of money in this country,” said Angelini, the president of Mercy Housing Lakefront, "on health care that is not getting people to a better condition.”

Vanessa Rivera contributed to this report while attending Marquette University and working as a research assistant to O'Brien Fellow Guy Boulton.