Mayor Marty Walsh is President Biden’s pick to serve as Labor secretary. Assuming he’s confirmed, he’ll be succeeded by City Council President Kim Janey, but the early favorite to win a full term in the fall is Michelle Wu, another member of the City Council.

When Walsh was elected back in 2013, there was only one woman on the City Council. Now there are eight, with seven of the 13 councilors being persons of color. “I’d be very surprised if we had another white man as mayor of Boston, which is all we’ve ever had,” says Boston University political scientist Katherine Levine Einstein.

There’ll be changes of the guard at city halls all across the country this year. With incumbents stepping down for term limits or other reasons, it’s guaranteed Cincinnati, Fort Worth, New York, Seattle, St. Louis and St. Petersburg will elect new mayors. Other major cities, including Atlanta, Charlotte, Detroit, Minneapolis, New Orleans and San Antonio, will hold contests as well.

In contrast with many other political posts, candidates running for mayor see it as a capstone to their careers, rather than a stepping stone to higher office, says Einstein, who helps run the Menino Survey of Mayors. “A small number of them do have other ambitions, but for a lot of them, this job is the be-all and end-all," she says.

The question is why anyone would want the job. Big-city budgets have been mangled by the pandemic. Downtowns are mostly ghost towns, and it’s a huge question mark whether office workers will return en masse. More immediately, cities are facing enormous challenges with housing and eviction, struggling transit systems and, in many places, rising crime and murder rates. “Public safety has never been a more prominent issue among the electorate in the city of St. Louis than it is today,” says Terry Jones, a political scientist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis (UMSL).

Even as cities face new challenges, many candidates are running on pre-pandemic platforms, arguing that the accumulation of income and rising property values in cities over the past decade has not been widely shared. Concerns about equity and racial justice have become even more prominent following protests last year. “There’s a lot more discussion of economic redistribution and racial justice than we’ve heard in past contests,” Einstein says.

That – along with demographic change – is what makes this year’s mayoral election in Boston different. Typically, the winner of a Boston’s mayor’s race has not been a visionary or a big-picture thinker, but rather someone concerned with the nuts-and-bolts involved in running a city, says David Paleologos, a Suffolk University pollster.

This year, the race is not about potholes and parking. Or, not as much.

“A lot of candidates in this field are going to want to talk about climate change and health care and bigger issues that are important to the global community,” Paleologos says. “That’s part of their genetic code.”

Past Generation Progressives

This year marks the passing of most, though not all, of a group of mayors first elected in 2013. Their efforts were not coordinated, but after taking office, new mayors of cities such as New York, Charlotte, Minneapolis and Seattle found that they’d run on similar progressive platforms.“There was an awakening about progressive policymaking and the need for it to happen at the local level,” says Pittsburgh Mayor William Peduto, who is seeking a third term this year.

They were then at the vanguard of the Democratic Party’s shift to the left. Several mayors collaborated with the Obama White House on issues such as minimum wage increases, early childhood education, paid sick leave requirements and My Brother’s Keeper, the administration’s initiative to address opportunity gaps faced by young men of color.

Once Donald Trump was elected to the White House, it seemed some mayors hadn’t moved left far or fast enough. When she was elected in 2013, Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges was seen along with a younger, more diverse city council as part of a break from the old union-influenced Democratic politics of the city. She lost after a single term, with progressives believing she hadn’t done enough to address income inequality or problems with policing.

In Seattle – one of the nation’s most prosperous and fastest-growing cities in recent years – much of the highly-liberal electorate believes that the corporations that have brought wealth and jobs are also to blame for income inequality and housing problems, including homelessness. Mayor Jenny Durkan, who fought off a recall attempt last year, decided to call it quits after a single term. She was unable to satisfy a city council that wanted to tax major corporations or protesters who occupied a “police-free” area near downtown.

Despite its winning streak as a city, Seattle hasn’t re-elected a mayor since 2005.

“Over the course of eight years, you get to see how anyone, no matter what their politics, becomes the establishment,” says Pittsburgh’s Peduto, who faces a challenge this year from his left. “It’s a natural progression, but you don’t expect it when your record has been not only taking on the establishment but having a basis of left-of-center politics.”

New Ways of Picking Mayors

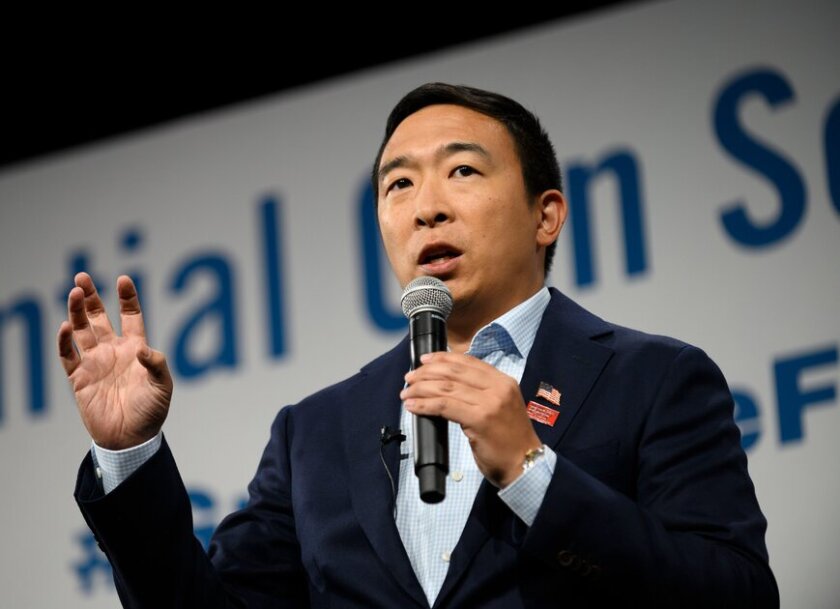

Bill de Blasio, another Class of 2013 mayor, is term-limited this year. He saw himself as a national leader on progressive issues. Although he made longer strides towards economic redistribution than he sometimes gets credit for, he flamed out as a possible progressive hero both in his no-hope presidential run and with his handling of the pandemic and other issues at home.There’s a large field running to succeed him, currently led by Andrew Yang, an entrepreneur who drew a following with his presidential run and call for universal basic income. “Yang has the name recognition and also significant social media exposure,” says Doug Muzzio, a political scientist at Baruch College. “There are significant questions to ask about his candidacy, like, does he know where the men’s room is in City Hall, does he know the neighborhoods.”

Other notable candidates include Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, and city Comptroller Scott Stringer, along with Raymond McGuire, a former Citigroup executive who has corporate support but little name recognition. The candidates have until the June primary to elbow themselves to the top of the field. “It’s wide open,” Muzzio says. “No one has broken through except Yang, who polls better than anybody else.”

This will be the first New York mayoral election to be held under a ranked-choice voting system. Voters will rank candidates from most to least preferable. If no one receives a majority on the first ballot, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and voters' second choices are counted up. The process continues until a candidate earns a majority of the remaining ballots.

Voters in the St. Louis mayoral primary next Tuesday will also have a novel way of voting. A ballot measure passed in November establishing use of a method known as approval voting in local elections. Fargo, N.D., is the only other city with approval voting. Residents will be able to vote for as many candidates as they’d like, but unlike ranked-choice voting each vote counts the same. The two candidates to receive the highest total will proceed to the general election in April.

This is likely to change the racial dynamics of the vote in St. Louis. Under the old system, the winner of the Democratic primary was certain to win outright. Four years ago, Lyda Krewson, who is white, took 32 percent of the primary vote, which was enough to beat several Black candidates who split the remainder, including city Treasurer Tishaura Jones and Lewis Reed, president of the board of aldermen.

Krewson opted not to seek a second term, but Jones and Reed are both running again. There hasn’t been any recent public polling of the race, but observers expect they will finish ahead of Cara Spencer, an alderwoman who is white. “I’d be shocked if it isn’t Jones and Reed,” says John Messmer, a political scientist at St. Louis Community College.

Whoever wins will have to confront the city’s problems with crime. Last year’s homicide rate was the highest in 50 years, including a disturbing number of child homicides. “More so even than the 1990s, the city is being devastated with news of the chaos in some of the neighborhoods,” Messmer says. “No matter where you live in the city, it’s inescapable.”

Jones, the UMSL professor, notes that St. Louis has an especially weak-mayor system, with more limited powers than nearly any other central-city mayor. It’s a frustrating position, especially in a city with a weak tax base due to high levels of poverty and median household income of just $35,000.

When she announced her decision not to run, Krewson noted that she’s “pushing 70.” Her inability to get what she wanted from the board of aldermen or even pick her own cabinet, along with protesters who forced her temporarily out of her home last year, were doubtless factors as well.

“Bottom line: It’s an incredibly, ridiculously difficult job for anyone,” Messmer says.