America’s long history of scapegoating its Asian citizens

When leaders call COVID-19 the “China virus,” it harkens back to decades of state-sanctioned discrimination against Asian Americans.

Danny Satow was walking home from a stroll around her neighborhood in Federal Way, a suburb just south of Seattle, when a heavy object slammed into her chest. A car whizzed by and a disembodied voice yelled a racial slur against Chinese people. The car melted into the rush of traffic, and Danny leaned over to pick up the liter of water that had hit her. Her collarbone stung, but she told herself it didn’t matter, she was fine. She stood still on the sidewalk and tried to channel her grandmother.

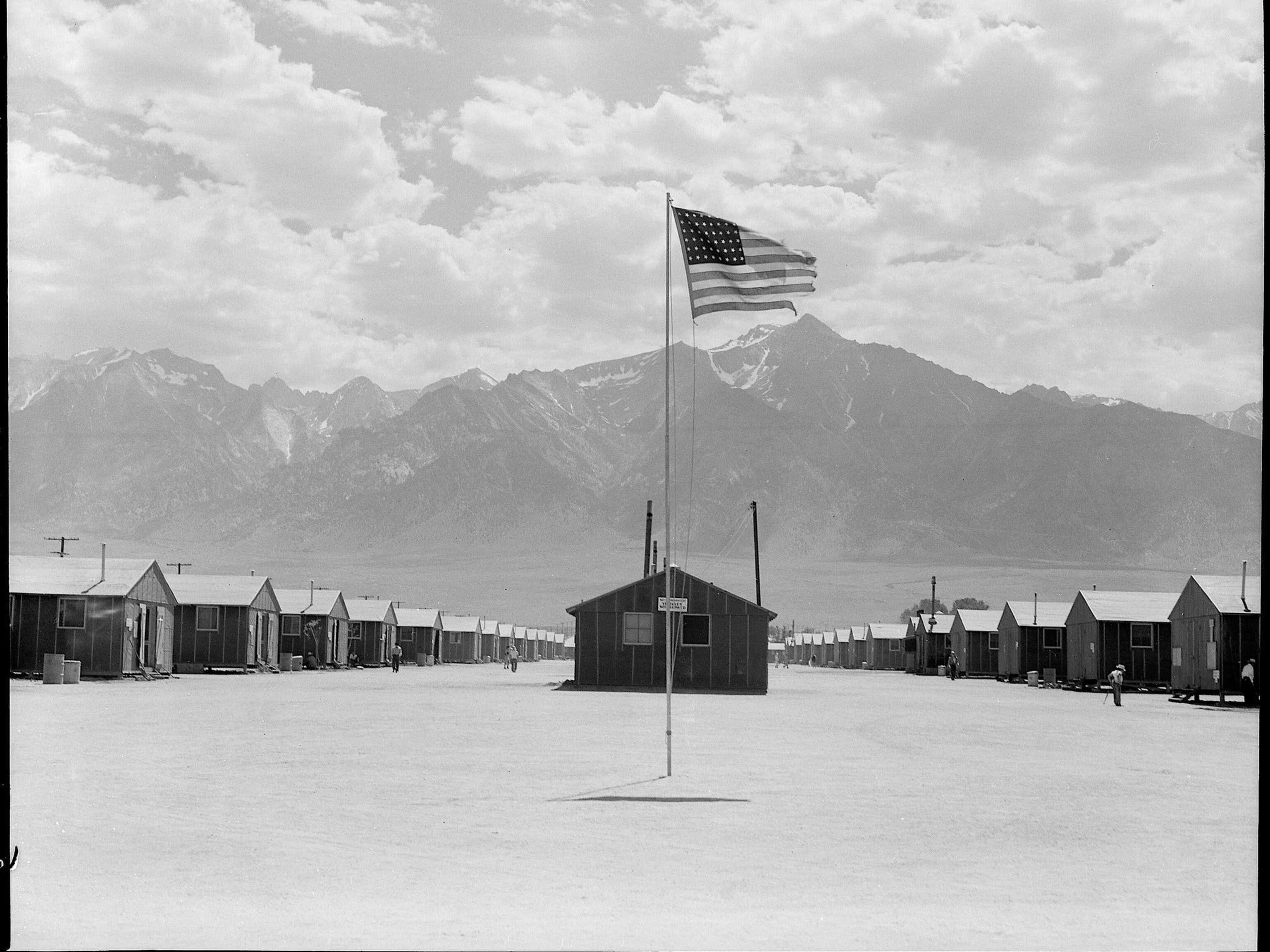

Growing up in New York, Danny rarely felt bigotry because of her Japanese heritage. But in the house she shared with her grandparents in Brooklyn, the past engulfed her imagination. Her grandfather, Eisaku "Ace" Hiromura, barely spoke of his experiences in World War II, but the medals hanging on his wall told of combat with the 442nd Infantry Regiment, a highly decorated unit of second-generation Japanese Americans. Her grandmother, Haruka "Alice" Kikuchi, regaled Danny with stories about being 20 years old and going to jitterbug dances held at the Tanforan Racetrack in California, where she and nearly 7,800 other Japanese-Americans were interred by the U.S. government. She and seven siblings slept on cots in horse stables.

Internment, she told her granddaughter, was a mistake. But she wasn’t bitter. We need to do better, Alice would say.

So when the water bottle hit her chest and the slur rang out, Danny, a 33-year-old physician assistant, thought of the optimism and poise her grandmother had maintained through her 101 years and counting. She kept walking. She was four blocks from home, but she burst into tears before she got to the end of the street.

A Brief Timeline of Racism Against Asians in America

In the months since the coronavirus pandemic began, thousands of Asians in the U.S. have become targets of harassment and assault. The racist incidents began as the first cases of coronavirus spread across China last December and disinformation reigned. As infections appeared in the U.S., President Trump repeatedly referred to COVID-19 as the "China virus" and "Chinese flu," and pushed a disproved theory that it had originated in a Chinese lab. By April an IPSOS poll found that three in 10 Americans blamed China or Chinese people for the virus.

For Asians in America, there is a new tension to daily life. Asian businesses and property have been vandalized with racist tags. Random individuals have been physically assaulted, verbally harassed, and shunned across the country. There’s no official tally for how many incidents have occurred, but in late March, California Congresswoman Judy Chu estimated 100 hate crimes were being committed against Asian Americans each day.

This fear isn’t new. In the past century and a half, the United States has made laws and national policies out of discrimination against ethnic groups, from the Chinese Exclusion Act to Japanese internment during World War II. Historians and activists fear that today’s targeted political rhetoric and harassment mirrors moments in U.S. history when racism became state-sanctioned.

THE DISINFORMATION WAR

In mid-February, when there was only a single confirmed case of coronavirus in Los Angeles, a 16-year-old student was accused by another student of bringing the virus into his school from China. When he replied that he wasn’t Chinese, his classmate punched him in the head 20 times. He ended up in the emergency room.

Manjusha Kulkarni was surprised. As the executive director of the Asian Pacific Planning and Policy Council (A3PCON), a coalition of organizations that represents 1.5 million Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Los Angeles County, she has a deep knowledge of anti-Asian racism in America. So, she was surprised to even feel surprised. Compared to African Americans and Latinos, Asians experience overtly violent racism less frequently, she says. (In fact, the “model minority” stereotype often pits Asian Americans directly against other minorities.) Plus, this was in a school. And the virus hadn’t yet gripped LA.

“So what does that say about the spread of the contagion of racism?” Kulkarni says. “It actually moves much more quickly than the disease.”

As the incidents of harassment against Asians rose, A3PCON asked the California attorney general’s office to collect data. It declined, so the organization built its own reporting pipeline. Within two weeks of launching on March 19, the Stop AAPI Hate tracker had received nearly 700 reports. From across the country, people described being spit on in grocery stores, yelled at on their jogs, and called racist names while waiting in line. (As of August, they have collected over 2,600 incidents.)

It would be a mistake to think of these as isolated incidents. There is a recipe for growing seeds of hatred into exclusionary national policy, Kulkarni says: Begin with political leadership that elevates the fear. Stir in media support. Top off with popular culture that perpetuates stereotypes.

“You really need that whole ecosystem, but it’s very easy, when there are these underlying beliefs, for America to snap back into it,” says Kulkarni. “It’s a constant fight because these racist tropes are really part of the American fabric. They’re more American than not.”

A HISTORY OF EXCLUSION

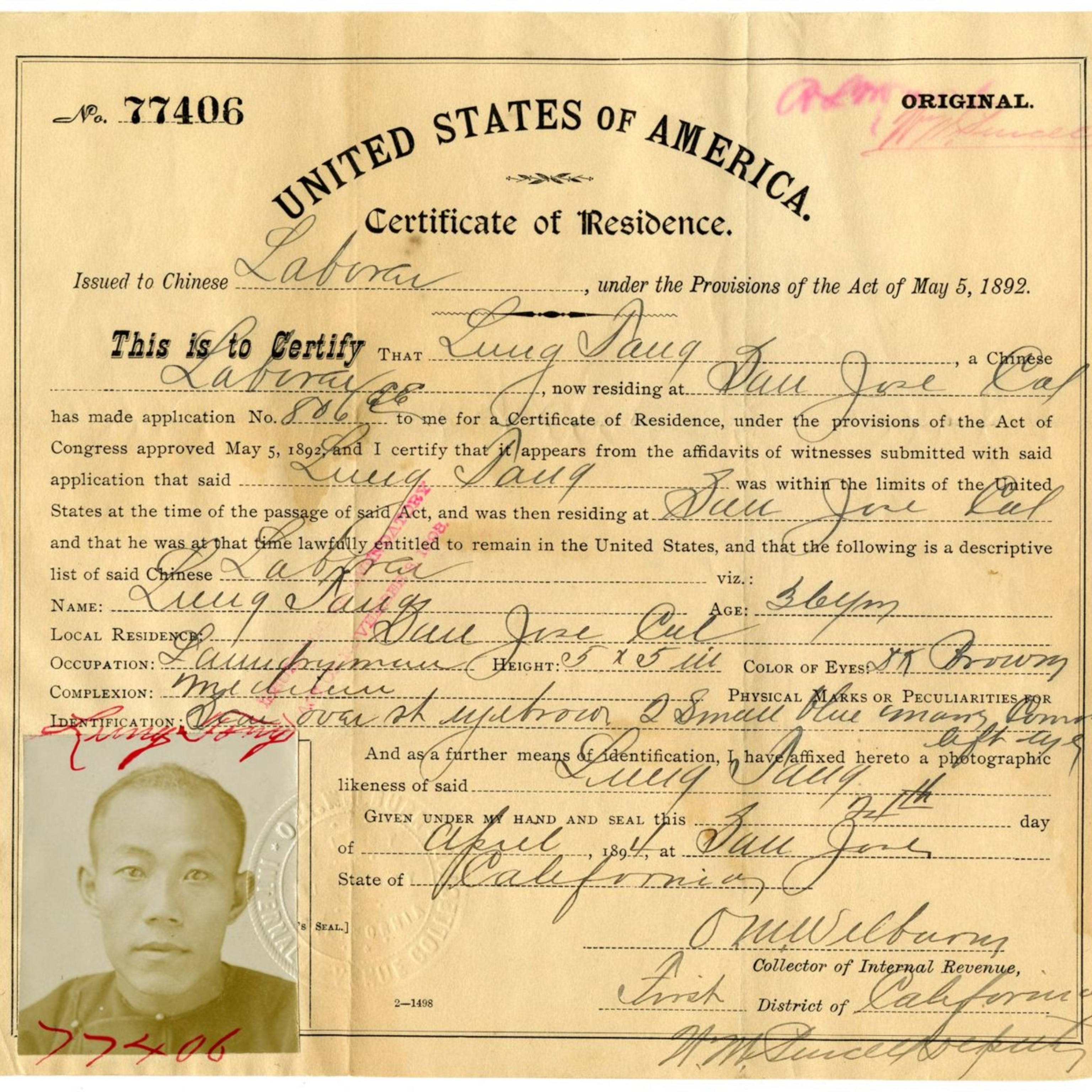

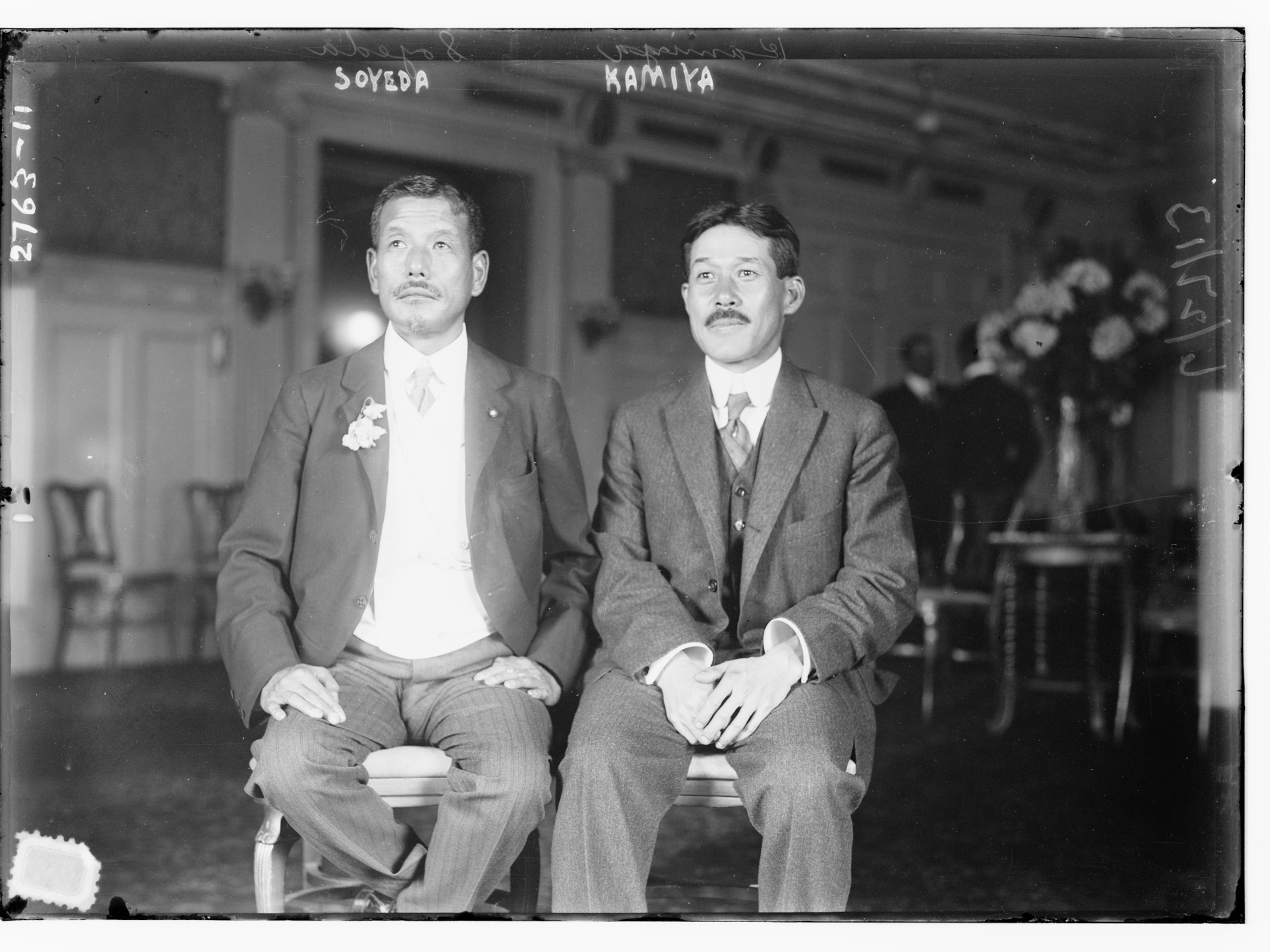

In the past century and a half, the United States has enshrined discrimination against ethnic groups into laws and national policies. In the 1880s, “yellow peril”—fear of an Asian invasion and resentment of the cheap labor coming from China—paved the way for the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning both new immigrants and existing residents from becoming U.S. citizens. At the turn of the century, a rise in Indian immigration sparked “dusky peril,” a fear of what a Washington newspaper then described as “Hindu hordes invading the state.” By 1917, after decades of pressure from anti-immigrant movements like "100 percent Americanism," the Asiatic Barred Zone Act put a halt to most Indian and Asian immigration. It wasn’t until the Immigration Act of 1965 that the race-specific barriers were removed.

During World War II, another perfect storm led to Japanese internment: Editors at newspapers like the Los Angeles Times voiced their support for the policy, while war propaganda depicted Asians as crafty and cunning. In one Dr. Seuss cartoon, rows of Japanese Americans line up on the West Coast to collect a brick of TNT. “Waiting for the signal from home…” the tagline says. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered more than 120,000 Japanese Americans into internment camps.

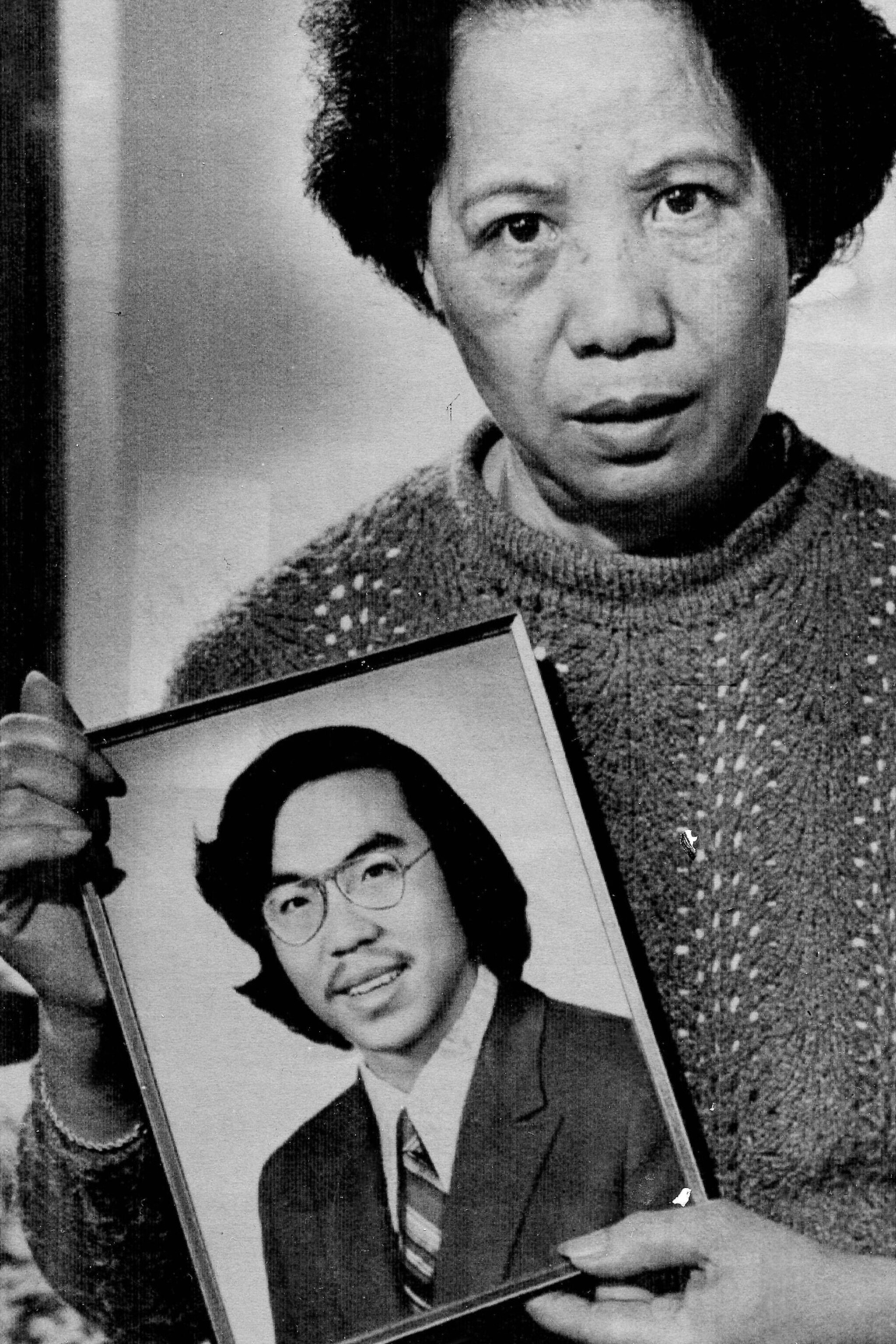

In the 1980s, Asian communities in America starting mobilizing to fight for their civil rights. The trigger was a murder: In 1982, Chinese-American Vincent Chin was beaten to death by two white men a few days before his wedding. The men held him responsible for Japan’s powerful auto industry at a time when America was losing manufacturing jobs.

After 9/11, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, many of whom were South Asian, documented scores of revenge-motivated crimes in the U.S. Among the first killed were Sikh gas station owner Balbir Singh Sodhi in Arizona, and Vasudev Patel and Waqar Hasan, two South Asians in Texas.

“Then you had the same thing you’re seeing now,” Kulkarni says. “Which is racist rhetoric employed by political figures, which then gets translated into extremely problematic policies.”

Today, the Trump Administration has continued directing blame for the virus toward China. A 57-page memo by the National Republican Senatorial Committee included a talking point for politicians to argue that calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” isn’t racist. In July, Trump claimed the Chinese government was "fully responsible for concealing the virus and unleashing it upon the world." The World Health Organization warns against associating diseases with specific locations, to prevent stigma and backlash.

The blame, Kulkarni says, is already rooted in the minds of many Americans. If racism wasn’t simmering just under the surface, she adds, how would her tracker have collected so many incidents of violence and harassment within the first weeks of the pandemic?

The vast majority of incidents collected by the Stop API Hate tracker are not hate crimes. They are unlikely to be brought to court. The only way to combat them is through education and public policy.

“When you have some of these components that are in the soil, do you ever get them out completely?” Kulkarni asks. “No. You have to constantly till the land. You have to constantly cultivate something better.”

THE NEW NEIGHBORHOOD WATCH

Three times a week, at 2 p.m., a small group of people in orange polo shirts bearing the hashtag “#Chinatownblockwatch” congregate at the intersection of Mott and Bayard, in the heart of Manhattan’s Chinatown. The volunteers, who come from as far as Queens and Brooklyn, spend the next two hours crisscrossing the twisted streets of Chinese bakeries and dumpling joints, peering down side alleys, and generally making their presence known.

They offer a simple message: We’re watching.

In January, as news of COVID-19 swirled, Karlin Chan started hearing rumors of Chinatown residents being harassed. Soon after, many stores were shuttered and streets grew quieter than ever. Chan, a full-time activist and advocate for crime victims, grew up in New York and knows his way around the streets. “I have a strict stand-your-ground policy,” he says. He started patrolling. He posted about his patrols on social media and a few friends joined. Then, dozens of people started showing up.

Chan believes incidents of harassment are more common than reported, especially after he started looking into reports of hate crimes around the city a few years ago. Immigrants often don’t know how to report a crime, or struggle with a language barrier, he says. Some prefer to stay off law enforcement’s radar. Chan offers himself as a one-man shop: He’ll encourage someone to make a police report, escort them to the station, and check on any unreported incidents he hears of. Without documentation, Chan says, there will be no resources or motivation to address racism.

“There’s always been a systemic, official and unofficial exclusion for Chinese, and this pandemic brought the debate back up again,” says Chan. “When they look for someone to blame, they blame the Chinese.”

“We’re acceptable,” he adds. “We’re never really accepted.”

Chan’s orange-shirted volunteers harken back to a time when neighbors had to watch out for each other. In the 1980s, vigilante crime fighters called the Guardian Angels patrolled New York’s subways and seediest neighborhoods. Chan plans to continue the patrol, and envisions it as a permanent Chinatown fixture.

“When we begin to understand the economic impact [of COVID], that’s when we’ll see more harassment,” Chan says. “Frustration turns to anger, and they’re going to vent their anger at us.”

A HISTORY DOOMED TO REPEAT ITSELF

America has been slow to acknowledge its anti-Asian history. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan apologized and paid restitution to survivors of Japanese internment camps. The Supreme Court ruling that enabled internment was overturned in 2018, and California apologized for its role earlier this year. In 2011, the U.S. Senate formally apologized for the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the House followed the next year.

But the full history is rarely part of public school education. “Part of the problem,” says Adrian De Leon, an assistant professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California, “is people saying this could never happen in America. The rest of us—whose communities have suffered this—can imagine it happening. That is the manufactured historical ignorance that allows this nativism, racism, and contemporary violence to fester.”

In the current political posturing, De Leon hears a racist stereotype that stretches back a hundred years. Before the Chinese Exclusion Act, newspapers and politicians pointed to poor sanitation in Chinese neighborhoods and described new immigrants inundating American cities. These points were embraced to justify exclusion, though living conditions in immigrant neighborhoods were more often due to a lack of government services. “These white native activists would ascribe that uncleanliness to Chinese bodies, and say this was a threat to the nation,” De Leon says.

Exclusionary policies and violence are often rooted in the threat of a rival global empire, says De Leon. Before World War II, the U.S. saw their interests in the Pacific at risk. Politically, he says, “the way the U.S. would frame a rising Asian superpower as a threat is then reflected onto people with that ethnic genealogy.”

Current events, he says, are following a disturbingly familiar framework.

“The use of history is to learn from mistakes of the past. But in a twisted, perverse way, what we see is that the U.S. continues to repeat the same historical processes that developed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.”

REJECTED BY THEIR COUNTRY

In Federal Way, Washington, Danny Satow didn’t leave her house for two weeks.

“I felt pretty ashamed that I was crying and running home, because my experience was so small compared to my grandparents’ experiences,” Satow says. “I felt I should have gotten over it and stayed strong instead of crumbling.”

Her friends asked if she’d noted the license plate, but she hadn’t. Her friends who also identify as Asian confided to her that they were “terrified,” she recalls. “They’re scared to leave the house and go to work.” Stares and offhand comments they’d otherwise brush off felt more menacing. She didn’t want to talk about it more, but they urged her to post about her experience on Facebook. With the tag “feeling worried,” she described the incident and wrote: “Stand up for those being targeted online and in person. It can be difficult to take action when under attack. Help us all be safe.” She also submitted an account of the incident to the AAPI.

Before the pandemic, Danny would visit her grandparents in their assisted living home in Vancouver, Washington, every couple of weeks. But the state was under lockdown. The incident had taken place on Easter—her grandfather’s birthday. She wrestled with whether to tell them what happened. Would it upset them? Would it look insignificant compared to their wartime ordeal? She finally decided not to mention it.

Four generations of her family had lived in America. Three had grown up as Americans. Nearly 80 years had passed since her grandparents had fought to be accepted by a country that punished them for their ancestry. She thought about her grandfather leaving home in Portland, Oregon, to go to war for America as his entire family was shuttled into internment camps. “They considered themselves Americans,” says Danny. “But they were fighting alongside people who viewed them as the enemy.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads