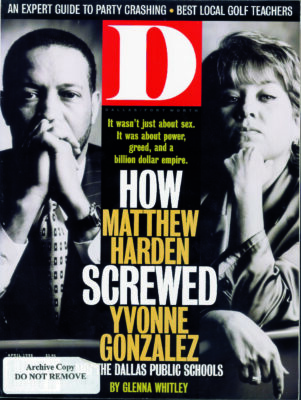

SHE CALLED THE M EET1NG AFTER WEEKS OF TEN-sion. The date was Aug. 20; they gathered in a nondescript conference room to discuss Yvonne Gonzalez’s demand that Matthew Harden resign his job as chief financial officer of the Dallas Independent School District. The press release was ready. This encounter was supposed to finalize Harden’s departure. But he begged for more time. He had been offered a private sector job in Seattle, he said, and the CEO was flying to Dallas to talk with him. Just let him get through that interview, and he would resign by the end of the month.

Gonzalez hesitated, and Harden asked the others if they’d leave the room. When he and Gonzalez were alone, she says, he moved close to her, leaned over, and whispered in her ear. “I love you.” Gonzalez, weary of the long conflict between them, but still full of affection for the man. blurted, “I love you, too. If things were different, I’d marry you.”

It was all a setup. In Harden’s pocket was a tiny tape recorder. The quiet murmur Gonzalez says she heard was not picked up on the tape. But her reply was-and it would soon become humiliating ammunition in their pitched battle for control of the Dallas Public Schools.

Tender feelings aside, she knew he had to go. Ever since Gonzalez had moved the district auditors out from under Harden’s control, devastating evidence of corruption had tumbled out. The revelations connected Harden’s division with fraud, contract shenanigans, misuse of purchase orders and payment vouchers, as well as the disappearance of inventory. The district was bleeding money, and investigative trails ultimately led back to Matthew Harden.

Contrary to the rumors and headlines and lawsuit allegations, none of this had anything to do with sex or about being black, white, or brown. It was all about green: money, and lots of it.

As CFO of a SI billion corporation. Harden controlled how every single dollar was spent in D1SD. For years, his position allowed him to cement his stature in the black community by controlling jobs, contracts, and other deals. And Harden knew that unless he got rid of Gonzalez, it was all about to end.

The Arrival of Dr. G

THE FIRST TIME SHE STEERED HER SILVER HONDA INTO THE parking lot of DISD’s headquarters, Gonzalez was startled. “I was absolutely amazed at the number of Cadillacs. Mercedes, Lexuses, BMWs. and Jaguars in the parking lot.” she says, “I walk in and see men in the halls wearing custom-made suits.” A career educator. Dr. Gonzalez knew how much school officials are paid. At the time, she shrugged and chalked it up to Dallas’ reputation for glitz.

Two years later, dressed in black, looking tired and resigned, eyes rimmed with red. Yvonne Gonzalez stands beside a floor-to-ceiling window in a downtown office tower, arms crossed, looking out over the city and remembering April 1, 1996, her first day of work in Dallas as deputy superintendent. It was another lifetime ago. when Dallas held such promise for her. “I loved that job.” Gonzalez says. She tights back tears, then throws her shoulders back and her head up.

In Dallas for a few days, she wants to meet somewhere away from the public eye. She’s been spending her time at her parents’ home in San Antonio. Struggling with depression. Gonzalez wants to talk but knows that no matter what she says, the deep humiliation will always remain. To ride so high and to fall so low and so publicly, the realization still takes her breath away.

She’d been hired away from the much smaller Santa Fe, N.M., school district, where Gonzalez made friends among those who applauded the pay hikes she won for district personnel, and enemies among those who opposed the raises as extravagant. There was some unhappiness among Santa Fe taxpayers, as well, when they learned the “Texas Tornado,” as Gonzalez was called, had blown an $800,000 hole in their school budget before skipping away to Dallas.

Balance sheets are not her forte. “You can spin me in terms of finances.” she says. In a district the size of Dallas, with a budget of $1 billion and more than 200 schools to operate, that was a decided drawback.

Before Gonzalez agreed to take the Dallas post, she asked the district to hire her second husband, Chris Lyle, as well. Lyle, a short, quiet man who shunned the spotlight, has a bachelor’s degree in juvenile justice and an MBA, but he had been unable to find a job in Santa Fe. When a vacancy opened in the security department, Lyle got the job. He and Gonzalez moved to Dallas and rented a house on Lake Ray Hubbard for $1,960 a month, but she spent little time there.

From the beginning, Gonzalez’s hiring was met with glee by Hispanics. They saw her appointment as long-overdue recognition of their needs. But she quickly felt embattled by the black activists in the district, especially board member Kathlyn Gilliam, who had cut her political teeth in the district in the ’70s when African-Americans had to fight for every crumb of the pie. The racial politics on the board were ferocious and unrelenting. And Gonzalez soon discovered that superintendent Chad Woolery was totally intimidated by the racial maneuvering.

Anxiety over race, over who got what and who controlled whom, percolated through the administration building. “Everybody walked around on tip-toe, like they were on eggshells,” Gonzalez says. “They were constantly attacked for being racist.”

That first day in the Dallas parking lot, Gonzalez brushed aside any nagging doubts about her new job and walked into the building. As she reached for the door, a stunningly attractive African-American district architect named Gena Bradford opened it for her. Gonzalez characteristically does not remember the moment, but Gena Bradford does.

Months later, when Bradford’s boss, Matthew Harden, proposed she receive a substantial promotion, Gonzalez nixed the nomination. An embittered Bradford would bide her time until a press request for details of Gonzalez’s office renovations landed on her desk.

The Chief Financial Officer

INSIDE THE BLAND, FOUR-STORY ADMINISTRATION BUILDING on Ross Avenue, the bureaucratic pecking order is oddly reversed: The most important-and powerful-executives office on the first floor, not the fourth. Walking through the empty building on a Saturday some weeks ago, Matthew Harden remembers the tiny space he started in-on a back leg of the third floor, as an accountant with a newly minted bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas-in October 1977. He manages the trace of a smile, as if remembering the young man in that cubicle 20 years ago. He points out a cashier’s window he once manned and remembers the double-takes he got in the late ’70s-people in the district weren’t used to seeing black people handle money, he says, speaking so softly you have to lean close to hear.

In the years since, Harden worked his way down to the first floor, nearest the superintendent’s office. His small suite was nothing fancy, filled with bureaucratic-issue furniture and bookshelves overflowing with large notebooks of budgets and plans and proposals. The only personal touches: lots of eagles-fashioned of ceramic, wood, crystal, and brass.

From the moment he came to DISD, Harden was seen as someone with enormous potential. “He was a very bright, intelligent young man,” remembers Linus Wright, then superintendent. However, the key to Harden’s success was not innate brilliance, but hard work and wonkish attention to detail. “Matthew’s just a working machine,” says Bill Keever, the former school board president who says he became Harden ’a close friend.

“Matthew is rigid, calculating, and methodical,” says Keever. “There’s not a spontaneous bone in his body. Do you know what you’re going to have for breakfast in two weeks? Matthew does.”

Harden was hired by John “Bud” Bivens, now executive director of budget development, who discerned in the young man instincts commonly associated with master chess players. Bivens in time would report to Harden. “Matthew has an ability to take a situation and look at it and see what, if he does something, will happen five or six years down the road,” says Bivens. Harden rose through the ranks of accounting until 1988, when Marvin Edwards, DISD’s first black superintendent, in search of more diversity in the senior staff, plucked Harden out of the ranks and made him his administrative assistant.

After serving in Edwards’ office, Harden was named assistant superintendent for budget and finance. School board president Sandy Kress and board member Dan Peavy continually praised Harden’s business acumen in board meetings, and he continued to receive more responsibility. Peavy now says Harden “owes as much to me and Sandy Kress as he does to anyone.”

By 1992, Harden had become associate superintendent for management, with a salary of $90,000 a year, responsible for all operations in support of schools other than direct pupil instruction. He had mastered the complexities of a system that operates with federal, state, and local funds, under a plethora of guidelines and restrictions, with more than 18,000 personnel. It’s a job Linus Wright says Harden didn’t seem ready for.

Harden says he had virtually no social life. Each day, he attended eight to 10 meetings, answered 30 or 40 phone calls, and replied to more than 100 pieces of mail. At night, he often went to board meetings.

When a department needed attention, Edwards would move it into Harden’s hands. “Whenever anything was broken, Matthew Harden got it,” says Keever. “He’s a can-do guy.” Harden was known as a stickler for the rules, unbending when it came to district money.

When Edwards left in 1993, new superintendent Chad Woolery promoted Harden to chief financial officer, despite the fact that Harden doesn’t have a CPA or an MBA. He had something more important: Harden knew how the numbers worked.

Terms of Endearment

AT GONZALEZ’S FIRST BOARD MEETING IN APRIL 1996, Matthew Harden introduced himself. Their first contact was brief. “I know who you are,” Gonzalez told him. “1 liked the way you handled yourself tonight.”

Since Harden now reported directly to Gonzalez, they scheduled time to meet. He expected the discussion to take place in her office and was surprised, Harden recalls, when she suggested that they get together for lunch. At the restaurant, Gonzalez asked him to talk about himself, his background and his operation, and seemed to be trying to put him at ease. He was impressed with her commitment to education, to “the kids.”

They were soon spending a lot of time together. The coming year’s budgets had to be assembled, and it was Harden’s job to bring Gonzalez up to speed. She remembers her amazement at the breadth of his duties. Within days, Gonzalez realized that Harden, not Woolery, wielded the real power in the administration. Harden was the only one who understood the budget, a fact that frustrated many other senior-level employees who confided to Gonzalez that they couldn’t figure out what money they had available for their departments. He controlled the position control numbers-determining who got hired and when-as well as every dollar the district spent. And he did so without fear of being second-guessed. Not only did the internal auditors report to Harden, so did the external auditors. The school board was embroiled in racial politics and was too unfocused (and perhaps incompetent) to concentrate on the numbers. He was beyond review, in total command of a vast financial empire.

Gonzalez struggled to understand the way the district’s finances and bank accounts worked. The annual budget explaining how the federal, state, and bond funds would be spent was 6 inches thick. The district had eight bank accounts. Three required signatures, including that of the superintendent, the board president, and the district treasurer, others were for deposit and wire transfers only. She didn’t understand the various accounts and how they operated. Harden seemed to be the only one who grasped where everything was and how the money moved.

The two administrators couldn’t have been more different. Six feet tall, soft-spoken, serious. Harden is most often a study in stoic self-possession. Camouflaged behind impeccably tailored suits, crisp white shirts, and cuff links, Harden melted into the background at board meetings-until a trustee wanted numbers. Vivacious, warm, barely 5 feet tall, Gonzalez has a fondness for high heels and sexy suits. She makes eye contact. She touches. She draws people in.

Despite their differences. Harden and Gonzalez quickly became friends. She loosened him up; he taught her the ins and outs of district operations. At first. Harden seemed to like her attentions, the way she rubbed his shoulder when she said hello, the way she sat so close. Each day, Gonzalez scheduled regular meetings with him that lasted three and four hours. If he didn’t show up on time, she’d send a secretary to find him. They would close the door, with orders not to be disturbed.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1996, both agree their relationship deepened, not only professionally but personally. “I thought Matthew was very bright,” she says. “He seemed to have all the answers about finance. That wasn’t my strength.”

Still, Gonzalez remembers being taken aback by the “quiet arrogance” with which Harden and his ever-present friend, Michael Henderson, walked the halls of 3700 Ross Ave. Both Harden and Henderson had expensive tastes, but Henderson was more flamboyant. Though Harden was always well-dressed, Henderson’s wardrobe was far more expensive and extensive, One board member teased Henderson about wearing shoes that cost S1,000 a pair, but no one seemed to wonder how he afforded them. Harden drove a Mercedes; Henderson drove a Jaguar- though his compensation never topped $100,000, By 1997, Harden was making $117,000. “In my opinion, we ran the smoothest operations in the district,” says Henderson. “Matthew is a very task-oriented person.”

The two had met in 1980, when Henderson was hired by the district as a “Title I Planner,” purchasing equipment for schools with federal funds. After Harden became CFO. Henderson was promoted to head of the facilities department. In his job, Henderson managed a budget of $80 million and controlled the largest number of jobs in the district. “Michael was incompetent,” says one longtime administrator, who asked not to be named. But Harden protected him.

Though others at DISD believed they were cousins and had roomed together at the UT, neither was true. But Harden and Henderson were close. Both had a passion for sports and often played basketball together. And they built houses next-door to each other.

With Harden-and most others-Gonzalez rarely talked about her personal life. She worked long hours and never mentioned her husband. Harden says she told him she wanted to move downtown but never told him that she’d rented an apartment on Cole Avenue. Gonzalez never visited his home in DeSoto. Though she knew that Harden and Henderson were neighbors, she was later startled to see a picture of Harden’s expensive house in the paper. She remembers Harden telling her “he had driven the builder crazy” with demands for changes.

Harden told her that he had other businesses outside the district and let it be known that he was close to Mayor Ron Kirk and his wife, Matrice. What seemed to matter most to him was his reputation among city leaders as a good businessman who kept the district on a tight financial leash, maintaining a coveted A-bond rating.

“He mentioned he was in the diamond business and that under Marvin Edwards’ administration, he had tons of time to be able to pursue business outside the district,” Gonzalez says. “[In those days], he would go to cocktail parties, the social circuit, and special clients still came to him to buy diamonds.” She teased him because, though Harden carried lots of cash, “he was the biggest skinflint.”

Though Harden was extremely private, she learned he was divorced and had two children. He was engaged to marry Lynette Howard, a teacher and girl’s coach who worked at a DISD high school. Harden showed enormous pride in his two sons and confided to Gonzalez he supported his sons’ mother so that she didn’t have to work. He had even started substantial trust funds for them. But when she tried to get him to talk about his fiancée, he would change the subject.

Gonzalez had been deputy superintendent for only a few months when the school year ended. In June, when all promotions and personnel changes are made for the next year. Harden came to Gonzalez with his own list of promotions. She was surprised to see that he was recommending that Gena Bradford leap over several other people with far more seniority to the No. 2 slot in his office, with a substantial pay raise.

Bradford, who worked in Henderson’s division, had come to the district a year earlier. When the school board approved a complicated energy management contract with Honeywell and Johnson Controls-which supposedly would save the district millions by installing efficient thermostats, lighting, and other cost-saving measures-Bradford was named liaison for the project.

Gonzalez was aware of rumors about Harden and Bradford, who was married and had two children. They frequently spent time together in his office behind closed doors and often ate lunch together. Bradford had started coming to board meetings, as if she were Harden*s administrative assistant.

But Gonzalez knew about Harden’s fiancée. Maybe the rumors about Bradford were not true, she thought. Even so, confronted by Harden with his list of promotions, Gonzalez gave him a quizzical look and told him no-Bradford seemed very competent, but to jump over the others only a year after joining the district? It seemed to be a rare lapse in judgment by the ever-cautious CFO. Bradford later attributed it to jealousy.

After the summer lull, staff members returned to the administration building in late July and the annual budget preparation sent everyone into combat mode. A tax increase was looming, ugly arguments over who would get what were beginning, and Woolery was nowhere to be found. In fact, under increasing pressure from various members of the board, Woolery was looking for another job. In mid-August, when Woolery announced he was leaving for the private sector, Gonzalez was named acting school superintendent, which made her an obvious candidate for the permanent post.

Gonzalez and Harden acknowledge that until the early fall of 1996, they had enjoyed a close, personal relationship, with a hefty dollop of sexual tension. According to others, there were stolen kisses in cars and secret notes. “You will find me wildly unpredictable in a personal sense, fairly predictable in a professional sense,” Gonzalez wrote Harden. “So don’t be surprised if I catch you ’off-guard’ (you may even get to like it).”

But during the summer of 1996, Harden says, he grew increasingly uncomfortable with the amount of attention he was getting from Gonzalez. He complained to friends that she was always paging him, leaving phone messages, sending memos and cards with sexual overtones. Gonzalez wanted him to go away on business trips with her. He told another that she’d called him one evening from a local hotel and asked him to bring her some papers. After he brought the papers to her room, Gonzalez had unbuttoned her blouse, but he had fled, leaving her in tears.

Gonzalez declines to describe any encounters but denies that their relationship was one-sided or that she pursued him sexually. She admits that she sent him notes and called him frequently but says none of the messages was sexually suggestive.

There are those close to both, including people in Gonzalez’s office, who believe Harden and Gonzalez had an affair. But Harden insists they did not, and Gonzalez is just as insistent. “Matthew was a close confidante.” Gonzalez says. “But we did not have a sexual relationship.” Still, it’s hard to imagine that a woman would send a card to a man she addresses as “Heating Pad” if they had not been intimate, (Gonzalez does not deny she wrote the cards released by Harden later.)

Both also say that by the fall of ’96, their mutual attraction had cooled. But their friendship was still intact. She still had great confidence in his abilities. When Woolery left, Harden confided to Gonzalez that he was thinking of leaving the district as well. He wanted to get his 20 years in for his retirement benefits- which would be fully vested in January 1997-then pursue things in the private sector.

’’He had a master plan,” Gonzalez says. “Matthew Harden was always 10 steps ahead of everybody else.”

She encouraged Harden to stay at least another year. Now that Gonzalez was acting superintendent, she needed his expertise, his support.

A Culture of Fraud

EARLY IN HER TENURE, EVEN WITH HER LIMITED FINANCIAL expertise, Gonzalez realized that the district finances were not nearly in as good a shape as Harden had assured her they were. “I came to believe the district was hemorrhaging financially. It seemed almost as if an intricate shell game was going on,” Gonzalez says. “When one department’s finances came under scrutiny, all of a sudden that area would be healthy.”

Gonzalez realized that other senior administrators, especially those not in Harden’s direct chain of command, resented him. No, it was stronger than that. “They hated and feared him,” she says. Staffers complained, she says, that Harden used his power to withhold funds and thwart the How of materials to sabotage other administrators, then take over their departments. After listening to numerous complaints about budgets from her cabinet members, Gonzalez had finally asked Harden, “Can’t we just have a plain explanation of our budgets?”

Several school board members, especially Kathleen Leos, were complaining to her about the budget and finance system as well. In Leos, Gonzalez had found a strong ally. A working single mother with five children, Leos holds a foundation job that affords little more than her ability to survive. She lives in a tiny ramshackle yellow house in an East Dallas neighborhood that is as close as Dallas gets to a melting pot. A Catholic of Irish descent, Leos was married to a Mexican, is strongly committed to her children’s culture, and speaks fluent Spanish. When Gonzalez arrived on the scene, Leos had been on the board for less than a year, but she had become its most forceful advocate for Hispanic causes. The two women hit it off.

During the 1996 summer budget sessions, Leos stepped forward to lead the board when Keever went on vacation. “We asked Chad for input in how the budgets were built, the real meal and potatoes,” Leos says. “We didn’t get anywhere. The administration didn’t give us the answers we needed. We tried and tried and tried. It did not come. That’s how the institution operates. ’Keep the board in the dark and we can do what we want.’”

Trustee Roxan Staff, who had come on the board only a few months before, was also feeling frustrated. “I asked, ’What did we spend last year?’” Staff says. ’”What did various departments spend?’ No one knew.” The board was being told there would have to be a tax increase, but Staff was uncomfortable voting for that without evaluating the previous year’s expenditures.

Harden’s response was, “We’ve always needed more accountability.” Staff thought that was odd, since Harden was the person who was supposed to make that happen.

Gonzalez’s attempt to learn the district’s inner workings was continually overshadowed by the ongoing racial politics on the board. From the moment that Woolery left, there were many who wanted to stop her appointment. “1 felt like I had a target on me,” Gonzalez says.

Throughout the fall of 1996, Gonzalez was under siege. At board meetings, she was constantly being heckled by NAACP president Lee Alcorn, Dallas county commissioner John Wiley Price, and African-American activist Aaron Michaels. She felt they were trying to intimidate her into withdrawing from consideration as superintendent. Her reaction was to become more determined than ever to succeed-but also more paranoid.

Before she could go forward, Gonzalez needed to surround herself with people who were competent and whom she could trust. That fall, she realized that might not be so easy. Many administrators had worked in the headquarters building for 20 and 30 years. Some were clearly dead wood, and some had extremely close ties to board member Kathlyn Gilliam, who intensely disliked Gonzalez. Not only were people connected by longtime friendships, they were also related by blood and marriage.

It was a standing joke that Michael Henderson’s entire family-more than 30 relatives-worked for the district. Those Gonzalez knew about included his wife, mother-in-law, brother-in-law, and several cousins. “You could go to practically any division and there would be a blood relative of someone who acted as gatekeepers and funnels of information,” Gonzalez says. The tangle of nepotism was bewildering, and it only heightened Gonzalez’s belief that she needed her own palace guard to survive.

Somewhat daunted by the challenges ahead of her, Gonzalez was tempted by the prospect of a job in Washington, D.C, with the U.S. Department of Education. Talking about this period- when she had a chance to avoid the coming catastrophe-she begins to cry and seems to search for words. “I knew instinctively that my life was going to be hell,” she says. But growing up in a traditional Hispanic culture, fighting for privileges given without hesitation to males, made her determined to stick it out.

On Jan. 9. the school board met to decide her fate. She heard shouting behind closed doors. The black trustees-Gilliam, Yvonne Ewell, and Hollis Brashear-insisted the board hadn’t done a thorough search. Later, they privately admitted they would not be comfortable with anyone but a black superintendent.

Others, especially those some called the “Four Moms”- Roxan Staff, Kathleen Leos, Lois Parrott, and Lynda McDow- felt that of the candidates presented to them, the choice was clear: Yvonne Gonzalez would be not only the first Hispanic superintendent, but also the first female head of the district. To negotiate her contract, Gonzalez brought in attorney Marcos Ronquillo. On Feb. 10, she signed a contract for a salary of $194,000, plus incentives and benefits-over $ 100,000 more than she had been making only a year earlier in Santa Fe.

Riding High

FOR WEEKS, GONZALEZ HAD MET WITH HER SENIOR STAFF TO determine her cabinet, and not long after taking over, announced a sweeping reorganization of her administration. Gonzalez moved a number of low-level employees with ties to obvious enemies out of her office and brought in a woman from New Mexico to work as a secretary. But she kept Freda Jinks, the most senior administrative assistant.

Gonzalez liked Jinks. At 52, she had been at the district for more than 20 years and, at one time, had worked for Matthew Harden as a budget specialist. Energetic and a little flamboyant. Jinks drove a new red Corvette and said she had been married five or six times. She often bragged about hiring private detectives to squeeze soon-to-be ex-husbands.

In addition to her district salary of $58,000 a year. Jinks had a business on the side: a desktop publishing company called Vidal Computer Graphics, which she ran out of her house in Piano. She made funeral cards, party invitations, and the like. Jinks told Gonzalez and others she had a net worth of $2 million, mostly in rental properties. “I’m a slumlord,” she joked one day when a renter called the office to complain that a bathtub had fallen through the ceiling. But Jinks had a skill important to the newly installed superintendent; She knew the district inside and out, and she knew how to get things done. “Freda knows how to broker the system better than anybody,” says communications head Robert Hinkle. “She could find money in budgets better than anybody.” And she knew everyone’s foibles and failings.

But the appointments to Gonzalez’s own office were mere footnotes. Ignoring the NAACP’s demands, Gonzalez announced she had eliminated the deputy and chief of staff slots, reducing the role of the district’s most powerful black female executive, Shirley Ison-Newsome.

The response to her reorganization was outrage. Gonzalez had upended the system. But the most important change that Gonzalez made got little attention outside the walls of 3700 Ross Ave. The instigator was Kathleen Leos. Leos had been appointed chair of the business committee and was trying to read contracts-not just the short “executive summaries” board members usually received, but the full contracts. She also brought up something she had repeatedly asked of Woolery: to require the internal and external auditors to report not to Harden, but to the superintendent and the board, as they did in most other large districts. Gonzalez felt the heat and did what Leos demanded. She also set up a technology committee to deal with purchases of computers and other equipment. Under Leos’ pressure, Harden’s sphere of control began to shrink. He protested, but Gonzalez stood firm.

In the coming weeks. Harden began to realize that Gonzalez threatened the empire that he had built. As he watched her bull-in-a-china-shop moves, he began to plot a counter-strategy. In late July, he visited lawyer Bill Brewer. Following the meeting. Harden began to carry his tiny tape recorder with him and was absent for long periods of time from his office. He began to gather evidence. When the time was right, he went on the offensive.

Gonzalez may have been embattled at board meetings, but out in the city, she encountered enthusiasm. Hispanics greeted her appointment as if she were a messiah promising salvation through education. Gonzalez was greeted almost as reverently by CEOs tired of the district’s constant headline-grabbing controversies. “She was on her way to being queen of Dallas,” says Hinkle. “She had charisma; she had everything.”

In February, with the zeal of a reformer, Gonzalez called in the internal auditor, Wesley Owens, who is African-American, and asked him to do a random check of timecards in the maintenance department. A few weeks later, Owens came to her with the results of his informal audit: Thirteen out of 50 employees checked at random-more than one in four-had been padding their overlime, some receiving more in overtime than their base salary each week. Gonzalez directed him to launch a large internal audit of hourly employees in maintenance. Then she called Marshall Smith in the district security office.

After Owens’ revelations about payroll abuses. Gonzalez asked Smith to put together a team of investigators to obtain timecards from several departments at the same time, before word could get out and evidence could be destroyed. Six investigators fanned out. One attempted to pick up timecards from the building facilities department, but Michael Henderson refused to let him have them. The investigator got Gonzalez on the phone. Henderson refused to talk to her. Gonzalez called Harden, and Henderson relinquished the timecards.

Meanwhile, Gonzalez had heard rumors about problems with contracts involving roofing and carpet. She asked Owens to dig into them as well. Owens began to bring her information about various contracts and the widespread misuse of open purchase orders, particularly in Michael Henderson’s department. On a contract for roofing repairs, an open purchase order for $250,000 had been crossed through and increased to $500,000. Payment vouchers for those and many others were signed by Michael Henderson-and by Matthew Harden.

Gonzalez discovered another purchase order for $800,000 that had been issued for “art supplies.” She went to board secretary Bob Johnston, who said, “Oh, it’s routine.” Harden told her the same thing. Though board policy explicitly limited open purchase orders to minor expenses less than $500, they were frequently used for large-scale purchases and projects, expenditures that by policy should have gone out for bids. Another common tactic was called “stacking”: breaking up contracts into amounts less than $25,000, then issuing payment vouchers to avoid going to the board for approval.

Gonzalez began to wonder: Was Harden incompetent or was he on the take?

She had thought that the fancy cars and expensive clothes and big houses had come from side businesses that everyone in district headquarters seemed to have. Now Gonzalez didn’t know what to think. When Harden came to her that spring and asked again that internal audit be moved back to his department, she refused. It was obvious to those around her that her once affectionate relationship with Harden had chilled. He would try to get an appointment with her, but, as Freda Jinks would later say, “something drastic happened where [Gonzalez] didn’t want him around there; she wouldn’t see him.”

On April 14, the internal auditors reported to Gonzalez that the district’s overtime expenditures were $2 million over budget. They had found significant overtime fraud, including employees who reported thousands of dollars in overtime in one pay period. Gonzalez told the board she was staying removed from the investigation, but the overtime was just “the tip of the iceberg,” and the problems “went all the way to the top.” The next day, she held a press conference and said she had called in the FBI.

Gonzalez also announced she was bringing in attorney Marcos Ronquillo to independently examine vendors and contracts.

Ronquillo began investigating civil fraud with an eye toward recovering money for the district. He passed along any evidence of criminal liability to a separate attorney. Gonzalez announced the creation of a hot line for employees and the public to report wrongdoing. It was immediately flooded with hundreds of phone calls from inside the district.

Corruption was so endemic that “the investigation” took on a life of its own, spreading throughout the district like kudzu. Throughout the spring, the FBI kept requesting records through subpoenas-150 payroll records at a shot. That led to subpoenas for inventories of everything from lawnmowers to computers. Harden frequently called Gonzalez, trying to find out what she knew about the FBI’s investigation. She said she didn’t know.

The publicity surrounding the investigations made Gonzalez’s already rising star shoot into the stratosphere, She was talking not just about educational accountability, but fiscal accountability, and a city deeply suspicious of its school district quickly embraced her.

But even as the city rallied to her, Gonzalez was discovering corruption so vast that it would be incomprehensible even to her strongest supporters. At one point, after learning some important files were in a warehouse, worried that requesting them officially would cause their shredding, she and several investigators staged an evening “commando” raid. Gonzalez drove a truck around the building with another staffer, while an investigator went in with a pair of bolt cutters, grabbed the files, and left.

As the internal battles mounted. Gonzalez’s need for absolute loyalty grew. She felt she had to get some of those she suspected of wrongdoing away from her by suspending them with pay.

However, personnel chief Robby Collins told her that she didn’t have enough evidence to suspend or terminate anyone. Violating due process was a sure way to get the district sued. She agreed to wait, but on May 14, an impatient Gonzalez met with Harden and told him to suspend four high-level administrators, including Henderson, saying that removing them would expedite the investigations.

Harden was forced to suspend his best friend-and next-door neighbor. The next day, Henderson resigned. “I couldn’t handle it anymore,” says Henderson, “There’s an effort here to exaggerate and embellish problems to make Matthew look incompetent.” But, as the audits continued, no exaggeration was needed.

At a cabinet meeting in late spring. Harden looked terrible, as if he had gone without sleep for days. He could not protect his best friend from Gonzalez’s reformist zeal, and worse, suspected he was also being targeted. Gonzalez, who had once told him everything, no longer told him anything. She had begun to realize that she might have to get rid of Harden.

Still, it all might have held together except for one thing: Kathleen Leos, who had just been elected board president, began scrutinizing the Honeywell/Johnson Controls energy contract. The staff was scheduled to report on the progress of the contract, which had been negotiated by Harden and was being managed by Gena Bradford.

Leos saw that on the board’s agenda for June 22 was a request from management that S1.2 million in bond funds be used for the project. “You can’t do this,” Leos says she told Harden on June 20. “It’s illegal; bond monies are designated money.” Harden told her he would provide more information within 24 hours.

A day came and went-Leos didn’t hear from Harden. Leos called board secretary Bob Johnston and asked him to contact Harden. “Tell Ms. Leos she has all the information she needs to make a decision,” Harden told Johnston.

“I was furious,” says Leos. “I felt he was lying.” She pulled the request from the board agenda. The next morning, Leos got on the phone with Gonzalez. “Why can’t we get solid information about both these contracts?” she asked. Gonzalez began rounding up various pieces of the contracts-which for some reason were scattered in different places around the building-and at Leos’ request, sent them on June 24 to Ronquillo for review.

The Storm

IN JULY 1997, GNZALEZ APPOINTED MARSHALL SMITH, AN African-American who had been a police captain in Philadelphia, acting director of the security department, which she had removed from Harden’s control. Smith lived in Piano and was not tied to Harden and Henderson. When Smith began reading various investigators’ reports, he was stunned. Hot-line reports had piled in, generating more than 500 investigations. Some reports were petty, others not: the wholesale theft of computers, carpet, televisions; contract fraud; people running outside businesses with district equipment; people getting paid but not working; friends getting contracts with no competitive bidding; even district food service trucks dropping off coolers stuffed with food at a local church.

“Something was wrong on a grand scale,” Smith says, “as if this had been going on so long and was so widespread. It wasn’t just one person. People had taken it on as a practice.”

Among those “practices” in some departments was a drill. Temporary employees were brought in and “tested” to see if they would violate the rules-such as fudging a payment voucher. If the custodian or secretary didn’t object, he or she got the job. And they had been morally compromised. Many people had a vested interest in keeping the lid on it because they were getting something out of it.

In fact, Gonzalez had compromised herself early on. She wanted new office furniture. There was no money in the budget, but Freda Jinks assured her it would be “no problem” to buy the furniture with district funds. In January, Gonzalez and Jinks went to Rosewood Furniture Store on Midway Road and purchased $9,000 worth of office furniture, which she later told the board she brought from Santa Fe. Gonzalez also wanted to furnish an apartment on Cole Avenue, which she had rented to be closer to her office so she didn’t have a long drive home when she stayed late at work. She picked out $7,000 worth of bedroom furniture.

According to Jinks’ later deposition, Gonzalez kept asking, “Are you sure we can cover the whole S16,000?” Jinks reassured her and prepared phony invoices on her computer to hide the embezzlement. Gonzalez says she didn’t know about the phony invoices until later-which seems unlikely. It seems equally hard to believe that Jinks, who later claimed she was afraid of Gonzalez, had never done this before. Months later, when Gonzalez told Jinks she was going to have to take the fall-“I’m too important; no one will care about you”-Jinks went to the FBI and cut a deal. (Jinks, through her attorney, declined an interview.)

Today, while she says she accepts responsibility, Gonzalez nevertheless insists she was set up for a fall; “You will never convince me that Freda Jinks acted alone in this.” But all she had to do was say no.

Smith updated Gonzalez every week, particularly on the investigations that involved associate superintendents like Harden. He says Gonzalez gave him specific instructions : to look at the investigation objectively, then send the information on to the attorney preparing criminal complaints to file with the FBI or DA. “To me, it seemed like she was being overly cautious,” Smith says. “She wanted to make certain it would be objective, that no one could yell bias, It made sense to me, but it still slowed things down a bit.”

In August, Gonzalez created committees to go over the proposed budgets for the coming year. One was a finance committee to review procedures with contracts and purchase orders. Harden came to Gonzalez and asked: “Why do we have to have a committee? Don’t you trust me?”

“No, Matthew,” Gonzalez told him. “I do not.”

Harden then suggested he be relieved of some responsibilities, a gambit Gonzalez read as his attempt to duck some tough questions. She refused the offer.

“I was not going to let him off the hook,” Gonzalez says. “He was responsible for all those divisions, and he was going to sit there and answer those questions-not push it off on some other schmuck. He was trying to keep his name from coming out, his reputation from being tarnished.”

The senior staff met over one weekend and went over their budgets. Gonzalez encouraged everyone to ask questions. During a meeting of the technology committee, staffers began challenging Harden’s numbers. His reaction was steely anger. “They basically called Matthew a liar,” says Gonzalez. “It almost came to fist city. I could tell Matthew had never been challenged like that.”

Press Attack

WHEN THE PHONE ON HER DESK RANG ON AUG. 6, GON-zalez heard the voice of FBI special agent Steve Sumner, who told her it was a courtesy call. That afternoon, Sumner said, U.S. Attorney Paul Coggins was going to announce 13 indictments for payroll fraud. “Great!” Gonzalez said, glad to hear that the FBI was doing something.

Fifteen minutes later, her office phone rang. It was Harden, panicked and agitated. “It is true the FBI is coming down with indictments?” he asked. “Do you know who is being indicted?” She said no, but the timing of the call set off alarm bells. Her office telephone must be bugged.

Gonzalez didn’t know it, but Harden had, in fact, been taping people with his microrecorder for weeks. When she encouraged staffers to speak their minds, it all went on tape. And he had taped her-in intimate conversations, in frustration, in full diatribe. Harden, sensing the erosion of his empire from the moment Gonzalez took office, had been planning a strategy. After agreeing to give an affidavit on behalf of Shirley Ison-Newsome in July, he had talked to Bickel & Brewer about representing him. Now, his best friend was gone, his reputation as a business genius was under attack, and his brother had been fired (see p.92). Gonzalez was pressuring him to resign-and Harden didn’t want to go.

On Aug. 7, the first of Harden’s counterattacks hit the press: a story by Miriam Rozen called “Yvonne’s School of Accounting” appeared in the Dallas Observer, blasting her office renovations and citing the expensive use of overtime by employees in maintenance department-the very department Gonzalez was investigating. On July 30, Gonzalez had insisted Harden stand beside her at a press conference saying she didn’t know the renovation of her office suite had soared to $62,336, about five times the initial estimate. Harden, forced into the public eye, looked grim, as if he was seeing his own tombstone. He later told trustee Ron Price he was thinking of resigning because Gonzalez had made him He.

The Freedom of Information Act request fi led by the Observer for documents relating to the renovation had landed on the desk of Gena Bradford, the very person Gonzalez had turned down for a promotion. Now she saw an opportunity to get even. Bradford says that in response to the FOIA request, she asked for information from a district architect. He sent back information saying the superintendent’s office renovations cost $12,065. “I’m no fool,” Bradford says. “I knew the carpet alone cost more than $ 12,000.” (As a matter of fact, the carpet was DISD property and therefore was not an additional expense. And some of the work, such as wallpaper, was so poorly completed it had to be redone three or four times.) Bradford asked for more documentation and got another administrator “to pull up every work order associated with the project.” Bradford called purchasing and got the furniture requisitions. The documents Bradford gathered showed that renovating and furnishing the suite of offices cost $90,000.

A later audit dated Sept. 16 by KPMG Peat Marwick showed that the accounting system in the maintenance department, which showed a total of $62,337, was so flawed that any determination of the real cost was impossible. The documents gathered by Bradford included unsupported disbursements, duplicate disbursements, and costs related to a work order for a different renovation project. A total of $7,442.21 in charges had no supporting documentation. “Several instances were noted in which maintenance employees charged overtime and took personal days during the same payroll cycle,” it said. Of the 15 work orders reviewed, two had no maintenance employee approval and 11 had no department approval from the general superintendent’s office.

Bui the office renovation documents were not what stopped Gonzalez’s heart cold. Harden had prepared a report on the cost of the office renovations and compiled them in a “green book,” which he gave to Gonzalez. In it, Gonzalez saw a copy of a phony invoice for the office furniture. She had told the board she already owned that furniture; how did he get the invoice from Jinks? Harden, she realized, had his own ammunition. Was this a threat to use it? (Harden says he didn’t know about the furniture.)

Gonzalez confronted Harden about the Observer story. He said he hadn’t spoken to anyone at the Observer for six months. She asked Jinks to run a computer check of the telephone system, which showed that someone had called Rozen from the phone in Harden’s office and small conference room on July 21, July 28, July 30, and July 31.

Angry, consumed by paranoia, Gonzalez wondered what else Harden was up to. Beginning in late July, though they were in the midst of budget preparations, Harden seemed to be gone from the administration building for three and four hours at a time. Whom was he meeting with? Where was he going? What did he know about the furniture?

Telling Jinks that Harden was involved in “some kickbacks and mismanagement,” Gonzalez and Jinks came up with a plan: Jinks, who scheduled the electronics sweeps, met with Larry J. Steging of Security Information Services on Aug. 10, and hired him to begin surveillance of Harden the next day. But Harden drove too fast for the investigator to keep up, so another investigator was hired to install and monitor a so-called “tracker.”

“I absolutely put that tracking device on his car,” says Gonzalez. She felt justified because Harden received a $3,500 car allowance, making his Mercedes a district vehicle during office hours. Besides, she rationalized, 400 employees in his own division had tracking devices to monitor the whereabouts of district vehicles.

On Aug. 12, Gonzalez rode a “corruption-busting” bulldozer into a districtwide pep rally meant to get the teachers charged up for the new year. She was upset that Harden wasn’t there-he told her he was visiting his mother in Tyler,

That same day, she received internal audits of two contracts: Brushields, which installed door seals in schools, and Time Saving Construction, a roofing company. Both showed major problems.

The Brushields audit showed what appeared to be violations of board policy on bidding, overpayments, and irregularities with purchase orders, including the fact that by that time Brushields had been paid $636,407; the board had authorized only $90,000. If the account had not been audited, expenditures would have reached $1 million before the board learned about it.

The examination of Time Saving was also devastating. Not only was the work shoddy or never done, the owner, William M. Risby, was a convicted felon and had no insurance or performance bond as required by law. Henderson and Harden had approved payments to Risby totaling almost $1 million.

A later lawsuit filed by Ronquillo on behalf of the district against Time Saving alleged that the invoices were “an attempt to fleece the Dallas Public Schools by charging two, three, or four times as much as should have been charged.” For one school, Risby charged the district $150,000 for work that cost $3,619. “It appears that a majority of the payment vouchers were submitted to circumvent the district’s policy,” an auditor concluded. Why hadn’t Harden caught the problem when he approved the payments?

That same day, Gonzalez received a report describing 38 deficiencies with the Honeywell/Johnson Controls contract, including the fact that Johnson Controls had been paid S4.3 million for work that had not even been started. Not only that. Bradford, the woman who had negotiated the contract with Johnson Controls, had quit the district and gone to work for the company. Gonzalez made her decision: Harden had to go. But before Gonzalez could move, on Aug. 13, Harden found the tracking device and called the police.

Ready to put Harden on administrative leave, Gonzalez asked Robby Collins about the proper procedure and he urged her to let Harden resign instead. On Aug. 20, Gonzalez met with Harden, Collins, and Ronquillo in a district conference room. Il was at this meeting, Gonzalez says, that Harden tricked her into saying “I love you” on his pocket tape recorder. Harden agreed to resign by Aug. 31.

“In my desire to avoid a racial explosion over Matthew, I agreed,” says Gonzalez. “I didn’t realize it was a setup.”

Gonzalez felt triumphant, but Harden was stalling. On Aug. 25, in a conversation he taped, Harden begs with Gonzalez for more time. He has a job lined up; he’s just hammering out the details. The two sound genuinely amicable, like old best friends, but both are lying to each other. He has no intention of leaving- and she’s trying to shove him out the door.

Harden, in fact, was gathering more ammunition. He suspected Gonzalez was behind the tracking device. On Sept. 3, Bickel & Brewer filed suit against Paul Beasley & Associates, the PI firm that installed the device.

On Sept. 11, a story appeared in The Dallas Morning News quoting an affidavit Harden had given in the Ison-Newsome lawsuit, saying Gonzalez lied when she said she was not aware of any renovation costs more than $12,000. “I was at meetings in which she was specifically made aware of and approved the costs of the renovation,” Harden said. The next day, the Observer blasted her for running from “the facts” about her office renovations. Gonzalez decided she could wait no longer.

On the morning of Sept. 12, she went to the office of labor and employment lawyer Dan Hartsfield and spent four hours going over the audits, the payroll abuses, and the district’s personnel policy regarding termination.

That afternoon, after returning from lunch to Hartsfield’s office, Gonzalez was blindsided by a blitz attack from Hardenone she never saw coming. At 1:26 p.m., while Gonzalez was talking to a lawyer about how to get rid of someone who kept promising to resign, Bickel & Brewer filed Harden’s second lawsuit, against Security Information Services over the tracking device. Three hours later, it was followed by a third lawsuit, accusing Gonzalez of sexual harassment and invasion of privacy. There was proof, Harden claimed, on compromising tapes, in notes and cards. Those were followed in November and December by lawsuits against Leos, the board, and the district as a whole-for a total of six lawsuits. Seeing his empire crumble around him, the calculating, methodical Harden had struck back.

The Gonzalez lawsuit clearly had been in preparation for some time, with purple prose crafted by Bill Brewer for maximum mileage in the press: ’’Rarely is a case filed which so dramatically reveals a set of facts that screams out the word abuse! Yvonne Gonzalez has, for the entirety of her term as general superintendent, used her position to pursue her own personal, political, and purient [sic] agenda, trampling on the rights of others, including Matthew Harden, to do so…. Gonzalez then admitted to Harden that what was happening was in part due to the fact that she was jealous of other women around him and that, although she was married, she wanted to marry him.” The tape recording of their private conversation-minus his whisper-had come back to haunt her. (Harden denies he told Gonzalez “I love you” but did not provide the audio tape.)

Harden’s lawyers initially said he would settle the case if Gonzalez returned all those personnel she had fired or put on administrative leave to their jobs. But the next day, at 7 a.m., the demand had changed. Gonzalez had to resign. Members of Gonzalez’s cabinet were called down to Hartsfield’s office, where Gonzalez told them, “’Matthew’s got us all. He’s put listening devices in all your offices, put taps on your phones. He has stuff on the board; he’s going to take us all out.” In particular, she said. Harden allegedly had Collins on tape with racial slurs. “He’s the godfather of it all. I’m going to resign and take the hit for all of you.” If she did, then Harden would return the tapes.

And so, she was gone-leaving supporters stunned, but not as stunned as they would be two weeks later, when the U.S. Attorney announced Gonzalez had embezzled money to buy bedroom furniture. Starting to believe her own press releases perhaps, Gonzalez tried to bully Jinks into taking the rap. Jinks ran to the FBI, which wasn’t even looking in Gonzalez’s direction.

Reading the various depositions and affidavits given by those in Harden’s camp, Yvonne Gonzalez comes across as a vindictive, cold-blooded, paranoid hysteric, out to get the man who refused her love, and Leos-a woman of great spiritual strength, who demanded accountability-as her calculating, Machiavellian accomplice.

But the truth is that Gonzalez had matched wits with Harden- tempestuous emotion versus methodical planning-and lost.

Today, Freda Jinks, who abetted Gonzalez’s felony, is back at work at the district, peeved because it wouldn’t pay her legal expenses. Most of those Gonzalez tried to get rid of are back at their desks. Michael Henderson has gone to work as a mortgage broker. The internal investigations have been ended, but six FBI agents are still looking at DISD finances. “We anticipate working on this case with the FBI and 1RS for at least another year,” says U.S. Attorney Paul Coggins, “and anticipate additional criminal charges.”

Matthew Harden formally resigned on Feb. 19, 1998, and received a settlement of $600,000 from district coffers, which has been further strained by the legal expenses his lawsuits generated. He says he is evaluating job opportunities.

And, on March 3, Yvonne Gonzalez, carrying a suitcase, reported to Bryan Federal Prison Camp-one day early to avoid the press-to begin serving a sentence of 15 months.

Related Articles

Hot Properties

Hot Property: An Architectural Gem You’ve Probably Driven By But Didn’t Know Was There

It's hidden in plain sight.

By Jessica Otte

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert