In the back parking lot of a Denver community health center, there’s a blue bus. On it are the words ‘All of Us.’

Inside, a nurse pulls open a Velcro sleeve as she checks the blood pressure of Denver resident Angelica Nevarez. “In the past week, have you donated platelets, plasma or blood?” the nurse asks. Nevarez says, “no.”

This isn’t a medical exam or a COVID-19 vaccination. It’s all for research, through the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us Research Program.

The exhibit, called the Journey, is traveling across the country to engage communities historically underrepresented in medical research. Historically, medical research has left out all kinds of people, including those from a variety of ethnic and racial groups, women and people with disabilities — limiting modern medicine’s ability to precisely treat large populations.

After a two-year pause caused by the pandemic, the NIH project recently stopped in Colorado.

The program is inviting more than a million people from all walks of life to help build what it’s calling one of the most diverse health databases of its kind and improve medical treatment across diverse groups.

Nevarez agreed to answer survey questions and share medical information, including her DNA from urine and blood. That all goes into the giant research database. Nevarez said she’s glad to help.

“I think that is a good program. And I think that it's good to do this kind of stuff for everybody,” she said.

Nevarez is originally from Mexico. She said that the program’s diverse pool will create a powerful tool for researchers.

“I think that that's my main purpose to come here, just to show my people, my community.” said Nevarez. She leads a diabetes prevention program with Vuela for Health, a health promotion group working with the Latino community. “We do have to do this, we do have to participate.”

Why science needs participation from non-white people

The Hispanic/Latino community represents nearly 20 percent of the U.S. population but only about 5 percent of participants in clinical trials. That same tiny figure is true for Black Americans too, who make up more than 13 percent of the population, according to the program.

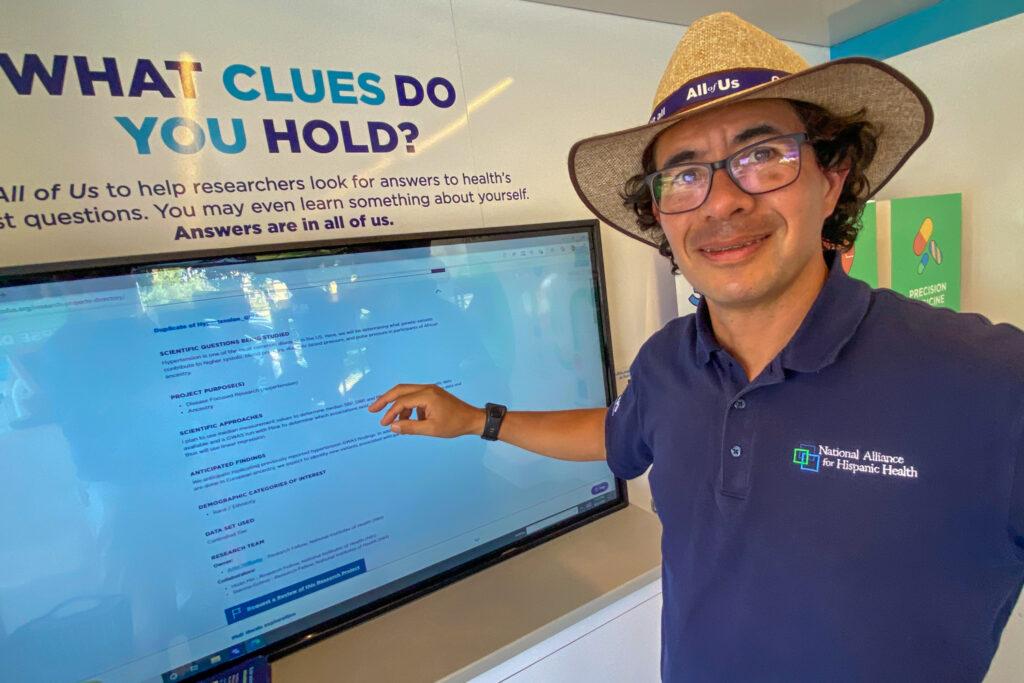

Often, people from diverse backgrounds haven’t been asked to participate or told why it’s valuable, said Edgar Gil Rico, an All of Us principal investigator with the National Alliance for Hispanic Health. “Why is it important for me? Why is it important for the community?” he said.

He answers his own question: to help with the development of medicines and treatments that are tailored to each individual. It’s what’s called precision medicine. He said health is not just a list of different symptoms that you have.

“The health of a person is more comprehensive. Where you live, what kinds of activities you do, your family health history, your genetics, all of these play a role in providing you the right treatment for you,” he said.

“It will improve treatments in the long run,” said Jaharri Asten, who came to the bus at the Lowry Family Health Center to provide samples of her DNA.

“I know a lot of people, especially minorities, feel like the doctors don't understand their culture,” she said. “And so having this data will help inform the doctors.”

Asten is a counselor in substance abuse and addiction with Denver Health and said better research could help improve treatment based on genetic and cultural differences. “So it would definitely be a good idea to have different samples so that medicine could be more specialized for each person,” she said.

Asten was excited about potential scientific advancements. “I just thought it was really fascinating,” she said. “Whenever I get the opportunity to participate in research, I do it because you never know who it's gonna help or who could be impacted in the future.”

“That medication works with white people,” less so for others

Across the U.S., more than 370,000 participants have completed all the basic enrollment steps, including providing a biosample, either blood, saliva or urine, according to an All of Us press officer.

Offering up your own DNA samples to build that database may be too much, too risky, for some.

But the program says the information is anonymized and the data is protected and secured.

Mayela Picado, a nutritionist from Boulder, said she was comfortable with the tradeoffs.

“I know how research works,” she said. “We are gonna be a number. So my genetics and all my information would be just a number.”

Alok Sarwal is a big proponent of this project. He leads a diverse medical clinic with offices in Denver and Aurora, the Colorado Alliance for Health Equity and Practice. It serves 20 ethnicities.

He’s encouraged community members to participate. “Not only we are contributing to the database, but we are also now going to be utilizers of the database,” said Sarwal, the CEO and co-founder of the clinic. Its mission is to improve the health of the state’s immigrant communities through culturally and linguistically appropriate prevention, health education, wellness activities, early detection, and self-management of disease.

His colleague, program manager Suegie Park, gave an example of how this information could help. She said there’s a popular blood thinner, developed by a pharmaceutical company. Blood thinners are key to stopping blood clots, preventing heart attacks and strokes.

“That medication works with white people,” research has shown, she said, more than 75 percent of the time. “Very effective!”

But it’s less than 50 percent effective for Asians, she said. And a big share of her clinic’s patients are Pacific Islanders, for whom it doesn’t work so well. Its effectiveness with “native Hawaiians is only 27 percent.”

These kinds of concerns are why the NIH created the project. The agency was well-aware that, “‘oh, we need multi-ethnicity,’” Park said.

In Colorado, 2,175 participants have completed all the basic steps, including contributing a biosample. Nearly 80 percent identify with a category the program calls “underrepresented in biomedical research.” This includes racial and ethnic groups, sexual and gender minorities, rural populations, older adults, people with disabilities and those with lower educational attainment and/or income, according to the program.

So far, 17 percent of Colorado program participants identify as Hispanic, according to the program; that’s a bit less than their 21.6 percent share of the state’s population. The numbers for other ethnic groups also trail their share of the Colorado population: 2 percent Black participants, compared to their 4.3 percent portion of the state’s population, 1 percent Asian (compared with 3.6 percent) and 1 percent American Indian/Alaska Native (compared with 1.7 percent).

How the All of Us research is making a local impact

The project is also drawing plenty of attention from researchers, like Dr. Nathan Clendenden, an anesthesiologist and professor at the University of Colorado.

He said cardiovascular disease, which includes heart attack and stroke, is the biggest killer. Typically he only studies patients in the hospital. But that is a limited number of patients and often doesn’t include everyone in the community, Clendenen said.

“I think that's been a blind spot in research is that it's not necessarily representative,” he said.

Now Clendenen and his team are exploring a new way to start addressing that problem. They’ve started a new study, about preventing blood clots, using the vast genetic database from the All of Us research program. (The title of the research: Platelet Hyperreactivity as a Therapeutic Target for Reducing Stroke in Older Adults after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement.)

“The drugs already exist. So this is really about taking existing tools and matching patients to them,” he said.

Clendenen said research done via the database promises to make medicine more precise, ideally personalizing the treatment of individual patients and improving, even saving, lives.

So far, 31 Colorado researchers registered to use the All of Us Researcher Workbench and nearly two dozen research projects have been initiated, according to the program. Those include studies of cardio-metabolic health outcomes, genetic risk factors for thyroid cancer, complications from cataract surgery, and Dr. Clendenen’s research on platelet reactivity as a risk factor for stroke.

(For more details, search the public Research Projects Directory.)

Another advantage for participants is to learn more about their own DNA. The All of Us program notes on its website it will only show results a participant wants to see.

That information may include genetic ancestry, including where someone’s family might have lived hundreds of years ago, genetic traits, such as why a person might love or hate cilantro, whether they may have a higher risk for certain health conditions and how one’s body might react to certain medications.

Program representatives “said you could learn about diseases that you might have, or like if there's any disorders or anything. So, of course, that's interesting,” said Asten, who is interested to see what her genetic profile shows. “You could see your ancestry and who your most recent ancestors are. So I thought that would be kind of cool too.”