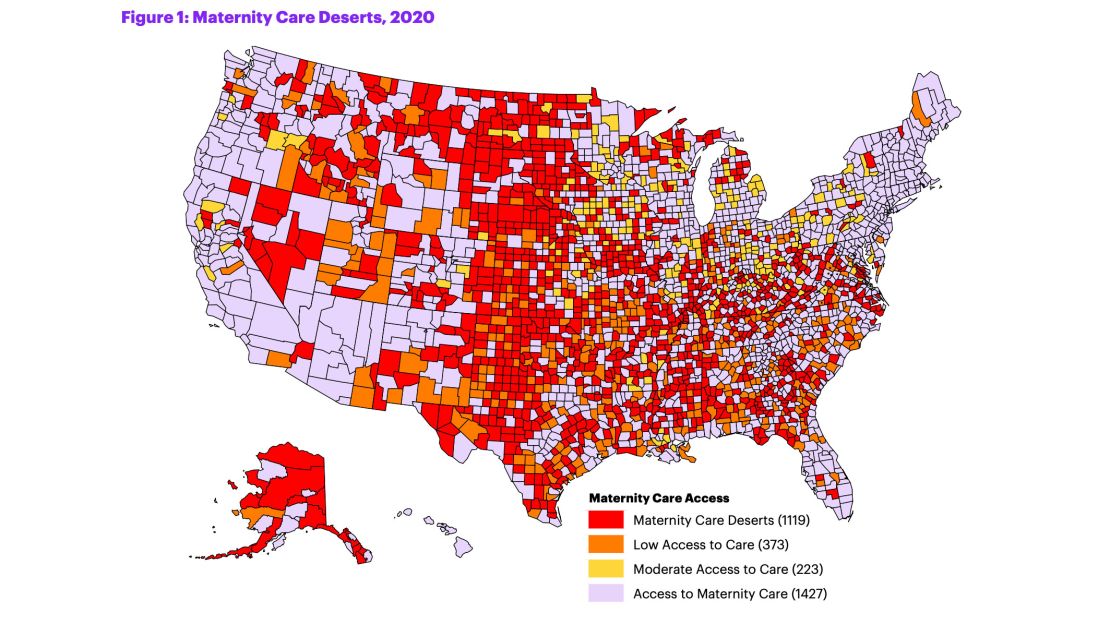

About 36% of all US counties are “maternity care deserts,” and the number of counties where there is limited or no access to maternity care appears to be growing, according to a new report.

The report, released Tuesday by the infant and maternal health nonprofit March of Dimes, found that between 2020 and 2022, 5% of US counties reduced maternity care access, but only 3% of counties shifted to increased access to care. Changes in the number of obstetric providers in an area were “the primary driver” for increases or decreases in access to care, according to the report.

Maternity care deserts can be associated with a lack of adequate prenatal care during pregnancy or treatment for pregnancy complications, and even an increased risk of maternal death.

More than 2.2 million US women of childbearing age – 15 to 44 – live in maternity care deserts, the report found. Overall, about 6.9 million women of all ages live in areas with little to no access to maternity care.

“They live in places where there is either no or limited obstetric care – counties that don’t have a hospital that offers obstetric services, no ob-gyns, no certified nurse midwives, no birthing centers,” March of Dimes President and CEO Stacey Stewart said. “Today, the US is considered, among all highly industrialized countries, one of the most dangerous developed nations in the world in which to give birth. And part of the problem with that, and part of the reason for that, is because of these huge gaps in access to care.”

Improvement in Georgia, decline in Texas

In the new report, March of Dimes researchers defined a maternity care desert as any county without a hospital or birth center offering obstetric care and without any obstetric providers, such as obstetricians, gynecologists and certified midwives or nurse midwives. The researchers noted that much of the data analyzed in the report reflects information collected before the Covid-19 pandemic and should not be interpreted as a direct result of Covid-19.

Among the counties designated as maternity care deserts in the report, about 2 in 3 – or 61.5% – are rural. It’s estimated that fewer than 7% of obstetric providers practice in rural areas, as obstetricians are more likely to work in metropolitan counties.

“We have seen a trend of the most of these maternity care deserts really existing in large parts of the South and some in the Midwest,” Stewart said.

“Texas has some of the highest amounts of maternity care deserts in a state, and in fact, between our 2020 report and this year, Texas has actually gotten even worse, where there are 12 counties in the state of Texas that have actually gotten worse in terms of access to maternity care,” she said. “Then on the flip side, a state like Georgia, which has some of the worst outcomes of maternal mortality and morbidity in the country, actually improved a little bit in terms of access to care.”

While the new report does not include any mention or analysis of abortion access, research shows correlations between maternity care deserts and states where abortion access is limited, Stewart said.

“Ironically, there is a bit of an overlap when you look at the maps of the maternity care deserts and when you look at some of the states that have passed these very restrictive laws,” she said.

In June, the Supreme Court ruled on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade, holding that there is no longer a federal constitutional right to an abortion and paving the way for states to ban abortions.

“We at the March of Dimes are monitoring the effects of the Dobbs decision. One of the things that we are absolutely certain of is that we have to make sure that in these places where care is already limited, we should not be doing things to further limit the care that women need,” Stewart said, adding that for maternity care deserts in need of more obstetricians, restrictive laws around abortion access could be a disincentive for attracting providers.

“We need to monitor this to see if this is really what will occur,” Stewart said. “But we’re already seeing some signs that there are concerns that care providers have about moving into places where their care may be misconstrued as violating a law.”

‘It’s quite concerning’

The March of Dimes report is “eye-opening” and “quite frightening,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, who was not involved in the new report.

“It’s quite concerning, and then on top of that, we know that that’s only likely to get worse as the baby boom generation that’s practicing medicine begins to go away, and I think everybody’s predicting some kind of physician shortage,” Benjamin said.

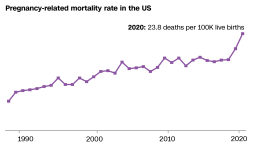

“We already know that we have huge disparities in ob-gyn care for pregnant women,” he said. “The biggest concern of course is access to care for women, and I think it means that both infant mortality rates run the risk of going up and maternal mortality rates run the risk of going up.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Benjamin added that city, county and state officials should pay close attention to whether their jurisdictions are maternity care deserts and, if so, determine what is needed to improve access to maternity care and get more providers in their areas.

“If I was a person responsible for making sure that we had adequate access in my community and I was looking for a solution to try to improve maternal child health, there’s certainly a blueprint there to get started,” he said, including expanding Medicaid coverage and the number of obstetric providers in the community.