Scientists have long suspected that the tiny plastic particles floating in the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers — consumed by a growing number of aquatic species — are anything but harmless.

Now, studies by a regional workgroup are beginning to clarify the connections between the presence of microplastics and the harm they could be causing in the Bay region. This research, combined with international interest in microplastics, is setting the stage for more informed management decisions and a flurry of additional studies.

Globally, microplastics have been found in the air we breathe, the food we eat and in human organs — even in mothers’ placentas. It’s possible that humans are ingesting a credit card’s worth of microplastics every week. One of the ways people consume plastics is by eating seafood, though the tiny particles can also be swirling around in tap and bottled water. Assessing the risk of plastic consumption by humans is one important research goal.

In the Chesapeake Bay region, researchers also want to understand how microplastics could be impacting local ecosystems and aquatic species. A workgroup of the Chesapeake Bay Program, a state-federal partnership that leads the Bay restoration effort, identified microplastics in 2018 as a contaminant of mounting concern. A 2014 survey of four tidal tributaries to the Bay found microplastics in 59 out of 60 samples of various marine animals, with higher concentrations near urban areas. A Bay survey the next year found them in every sample collected.

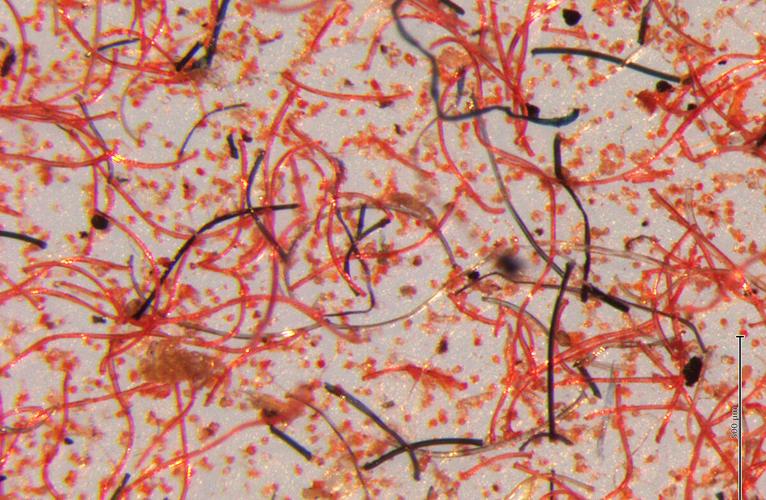

Plastic microfibers, shown here under a microscope, often slough off from the washing of synthetic fabrics and make their way through wastewater treatment facilities to local waterways. Such fibers are thought to be among the most common plastics in many river systems.

Microplastics are typically defined as plastic pieces between 1 micron and 5 millimeters in size. Smaller pieces are called nanoplastics.

Researchers classify microplastics in two ways.

“Primary” microplastics are tiny when they enter the environment. Examples include plastic pellets released by industrial facilities, synthetic microfibers in clothing released during wash cycles and tire fragments washed off of roads.

“Secondary” microplastics are created when larger plastic debris breaks down into smaller fragments as it’s battered by wind, sun and water over time. Polystyrene (often known by the brand name, Styrofoam) food containers, plastic grocery bags and plastic water bottles are in the secondary category. They easily break down into smaller pieces, making them priority targets for legislation that reduces their use.

Focus on striped bass

In spring 2019, the Bay Program convened a two-day workshop to evaluate what local experts did and did not understand about the impact of microplastics in the Chesapeake region.

The participants concluded in a follow-up report that microplastics “pose a potential serious risk to the successful restoration of the Chesapeake Bay watershed.” They recommended developing an “ecological risk assessment” for striped bass — a key Bay species, known regionally as rockfish — to provide a detailed look at how a living organism ingests microplastics and what happens when it does.

In response, the Bay Program formed a plastic pollution action team to head the risk assessment effort and produce strategies for reducing plastic pollution, a goal seeing revived political interest recently. The group also compiled standardized terms and measurements for the region’s scientists to use as they study microplastics.

And, after dredging up more questions than answers about microplastics, the 2019 workshop led the EPA to contract with Tetra Tech Inc. to help produce a series of reports on the subject, including the risk assessment for striped bass.

Striped bass from the Potomac River were selected because, as one of the top predators in Bay tributaries, they consume and rely on other species and habitats whose progress is integral to the restoration effort. They are known to consume both blue crabs and forage fish. Once under a fishing moratorium, striped bass were considered a success story of the Bay because of their rebounding population. Recently, though, they have faced setbacks. Their habitat, preferred diets and populations have been well-documented, and striped bass continue to be closely monitored under a regional fishery partnership today.

Discarded plastic objects wash into waterways and break down over time into tiny particles called microplastics.

The newly released risk assessment found a fair amount of circumstantial evidence, based on research involving other fish species, that microplastics could have harmful impacts on the Bay’s most iconic recreational species and, potentially, on the people who eat them.

The scientists did not open the bellies of local striped bass to look for plastic. Instead, they combed existing scientific literature — some of it coming out while the work was under way — to discern data gaps and identify where future Bay-region studies should focus their attention.

The assessment found that microplastics can harm fish in several ways.

- Tiny plastic particles can physically block or fill up the animal’s gut, potentially reducing its ability or desire to feed.

- Microplastics can cause behavioral changes as their presence changes a fish’s buoyancy or swimming behavior, which can make the fish more susceptible to predators.

- Microplastics also can carry toxic chemicals into the fish’s body, which could bioaccumulate as the fish consumes other prey that have ingested plastics.

While striped bass migrate outside of the Bay, they tend to remain in the estuary for the first few years of their lives, making them “an organism that can reflect the potential impact of microplastics in a specific location,” the assessment states.

Martin Gary, executive secretary of the Potomac River Fisheries Commission, advocated for focusing on striped bass rather than oysters or blue crabs, as had been originally suggested, because their lifecycle makes the fish a fitting indicator of their environment. Gary said the Potomac River is the second-most valuable spawning area for striped bass along the Atlantic Coast, behind the Susquehanna River.

“Pretty much all life stages of striped bass use the [Potomac] river at some point, even the larger animals that come back,” Gary said. “It’s not a species with specific outcomes in the 2014 Bay agreement, but its life cycle includes the health of crabs and oysters and sea grasses. Everything is interdependent.”

Also, because their numbers are once again in decline, striped bass also are “on everybody’s radar right now,” Gary said, as fishery managers consider whether to revisit an overarching management plan in light of recent declines in their population. If they do, microplastics could be a part of that conversation.

Eating plastic

Globally, researchers have found microplastics in the guts of enough aquatic species to assume they’re nearly everywhere, both in aquatic environments and in the creatures that inhabit them.

Eastern oysters, which live in the Chesapeake Bay, have been shown to confuse microplastic beads for food in a University of Maryland lab, taking the particles into their gut.

Plastic pieces float near a kayak in Virginia’s Occoquan River.

A researcher in Delaware Bay recently looked for microplastics in juvenile and adult blue crabs in two of the bay’s tidal creeks. Jonathan Cohen, an associate professor at the University of Delaware whose work has yet to be published, wrote in an email that his team found microfibers in 48% of crabs collected, mostly in their stomachs.

No one has done a survey on the stomachs of striped bass in the Potomac River yet, but evidence already exists that they would likely find microplastics. A study of microplastics uptake by species in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Nevada found tiny plastic particles in the guts of striped bass there.

Susanne Brander, a researcher at Oregon State University studying how microplastics impact black sea bass, spoke via video at the 2019 workshop about her findings, which could have some correlations to the Bay’s striped bass. While at the University of North Carolina, Brander found microplastics in 60% of black sea bass she sampled in the wild during a two-year project. This important East Coast species also visits the Lower Bay.

Because striped bass consume a broad array of other species over the first three years of their lives, their diet alone — a major focus of the risk assessment — illuminates the many ways they could be consuming microplastics in the Potomac River. Striped bass could be exposed to microplastics via their gills or by skin contact in addition to consuming them. But the assessment assumes, based on existing research, that “trophic transfer” — eating other species that have eaten microplastics — is a major mechanism of exposure.

How microplastics get into the fish matters. Studies cited in the assessment show that mysids, small, shrimplike crustaceans that striped bass regularly consume, can contain large amounts of microplastics. The same research shows that fish that consume mysids tend to bioaccumulate those plastic particles — storing them in higher and higher concentrations — and transfer them to fish tissue.

The assessment did not focus on which types of microplastic striped bass would likely be consuming. Preliminary evidence suggests that microfibers, like those that are shed by synthetic clothing or fishing nets, could be more abundant than disintegrating plastic in river systems.

As researchers were working on this assessment, microplastics research continued to be published. One study came from students at Susquehanna University in Pennsylvania, who found microplastic particles in the stomachs of smallmouth bass taken from the mainstem of the Susquehanna River in 2019. Each of the 89 bass contained an average of 29 pieces of microplastics, predominantly fibers.

Overall, the striped bass assessment is a starting point for further research, its authors said.

“This is a framework that starts showing the potential of different sources of microplastic contamination … to striped bass,” said Kelly Somers, physical scientist at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and co-chair of the Plastic Pollution Action Team. “Naturally, it will inform us of other species on that pathway, like blue crabs or [underwater grasses]. This is the first iteration — that necessary groundwork we need to lay to better understand that.”

Human impact

More information also is needed about threats posed to humans who eat the Bay’s fish, including striped bass.

“Given that striped bass are a popular recreational and commercial fishery species, there is potential for humans to become contaminated with microplastics from eating striped bass,” said Matt Robinson, environmental protection specialist for the District Department of Energy and Environment and a co-chair of the Bay Program’s plastic pollution action team.

Granted, he said, research is pointing to a growing number of ways humans could be consuming plastics already. “Still, we are very concerned here in DC about people eating plastic when they eat fish.”

Despite the ubiquity of microplastics, researchers and advocates are far from throwing in the towel. The plastic pollution action team also published in May a document that lays out what future microplastic monitoring should look like in the Bay watershed — and potential strategies for curbing sources of plastic pollution closer to the source.

“COVID trash” is now a common element in waterborne debris. Masks and gloves are among the types of litter that degrade into microplastics.

The report suggests an overarching monitoring program for microplastics that dovetails with existing monitoring programs and falls under the purview of the Bay Program. A subset of fish monitoring programs that collect and analyze stomach contents, for example, could also be used to garner microplastic ingestion data. The report also suggests collecting enough microplastic data that the Bay Program could set a related pollution reduction goal for the region or states could use it to inform their own policies and practices.

Globally, the production and disposal of plastics has continued to skyrocket in recent decades, with an estimated 33 billion pounds of plastic entering the marine environment from land-based sources every year, according to the nonprofit Oceana. The group says that’s roughly the equivalent of dumping two garbage trucks full of plastic into the ocean every minute.

Despite growing awareness about plastic pollution in recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have temporarily cemented reliance on certain plastics. A data analysis published in ScienceDirect indicated that the pandemic would “reverse the momentum of a years-long global battle to reduce plastic waste pollution.” Another study found the virus triggered an estimated global use of 129 billion face masks and 65 million gloves every month, enough to cover the landmass of Switzerland over the course of a year.

Volunteers who clean up trash along the Anacostia River had to create a new category for the sudden uptick in masks, gloves and other “COVID trash” they were finding floating in the water and stuck to the shorelines.

“That was one of the main things people picked up,” said Robbie O’Donnell, watershed programs manager for the Anacostia Riverkeeper.

Katie Register, executive director of Clean Virginia Waterways at Longwood University, said that, in some ways, 2020 felt like a lost year in plastics advocacy. But, in other ways, a lot of ground was gained.

“People used to sit in a restaurant eating off plates, and then for a year all that food has been in single-use plastics, for the most part,” Register said. “But, in spite of that, we’ve seen some real changes.”

Some are driven by new legislation.

New laws

Even as the research continues, recent legislation is attempting to reduce sources of plastic pollution.

A plastic grocery bag floats across a sidewalk in the District of Columbia. The District was one of the first localities to pass a 5-cent fee on the use of plastic bags.

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam issued an executive order in March that lays out a plan for state government facilities — including state universities — to stop by midsummer the use of plastic bags, straws, cutlery and other items. The order, which cites concerns for the health of the Bay and wildlife, also includes a plan to phase out use of all nonmedical single-use plastics and polystyrene objects by 2025.

Virginia also approved in March a plan to end the use of polystyrene cups and food containers. Food chains with 20 or more locations will not be able to package food in such containers as of July 2023 without being fined, while remaining vendors have until July 2025. The bill also restricts nonprofits, local governments and schools from using polystyrene takeout containers after the 2025 deadline.

The state also passed a local option to add a 5-cent tax on plastic bag use at grocery, convenience and drug stores as of this year. In May, the Roanoke City Council was the first to approve a local version of the tax.

Maryland lawmakers did not act this year on a proposed ban of plastic bags, but they did join Virginia and become the sixth state in the country to ban intentional balloon releases. Pennsylvania authorities completed a littering study in 2020 and began work in May on a Littering Action Plan intended to curb trash closer to its source.

At the federal level, California and Oregon lawmakers reintroduced an expanded federal bill called the Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act. The bill would require producers of plastics to help fund recycling programs while banning certain single-use plastics nationwide, placing a moratorium on new plastics production facilities and calling for additional research, among other measures.

“I credit a lot of this to growing concerns among people of all ages,” Register said. “People are more aware that plastic pollution is increasing, and it’s got serious impacts.”

(1) comment

As a commercial fisherman from cape charles area, One thing I see that needs to be outlawed is the sale of( ether or whatever they put in them) balloons. I see these most every day, and not just 1 or 2. Sometimes big knots of 10 or 15.

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

We aim to provide a forum for fair and open dialogue.

Please use language that is accurate and respectful.

Comments may not include:

* Insults, verbal attacks or degrading statements

* Explicit or vulgar language

* Information that violates a person's right to privacy

* Advertising or solicitations

* Misrepresentation of your identity or affiliation

* Incorrect, fraudulent or misleading content

* Spam or comments that do not pertain to the posted article

We reserve the right to edit or decline comments that do follow these guidelines.