by James A. Bacon

Ever alert to signs of racism everywhere, the Washington Post published this morning a lengthy article about COVID-19 and race. “Racial, ethnic minorities reel from higher covid-19 death rates,” proclaims the headline. “A Post analysis shows that communities of color continue to die from the coronavirus at much higher rates than Whites.”

The Post starts by taking note of the racial disparities in death rates:

As another wave of infections sweeps across the country this fall, losses among racial and ethnic minorities remain disproportionately large. Black Americans were 37 percent more likely to die than Whites, after controlling for age, sex and mortality rates over time. Asians were 53 percent more likely to die; Native Americans and Alaskan Natives, 26 percent more likely to die; Hispanics, 16 percent more likely to die.

The Post then proceeds to explore variety of explanations for the discrepancy, all of which fall under the rubric of “structural racism.” States the Post: “Minorities face a long history of unequal access to medical care — which may have impacted treatment decisions and outcomes.” For example, noting that African-American patients were more likely than whites to receive “an older, less-expensive and riskier blood thinner linked to higher morality from covid-19,” the Post quotes a scientist as “wondering” whether some doctors chose the older, more established product for minority patients because the newer drugs were overwhelmingly tested on whites.

Then the authors treat the conjecture as reality, further quoting the scientist, Venky Soundararajan, as saying, “It’s some of the same reasons people are protesting in the streets — police brutality, job discrimination, environmental justice. The coronavius shows how much racism there is in health as well.”

Perhaps there is something to the structural racism arguments My hunch is that most of the disparities can be attributed to socioeconomic status, a factor that the Post “analysis” totally ignores. But I’m not ruling a priori the possibility that some doctors and institutional structures are racist. That’s an empirical question worth pursuing. Here’s what I object to: The Post is ruling out a priori any other explanation.

In April U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams urged fellow African Americans to avoid alcohol, tobacco, and drugs to lower their risk from the virus. The Post article devoted one sentence to Adams’ words of caution, then quoted Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., to debunk him. “Waters,” states the article, ” described the comments as ‘a backhanded attack on African Americans and communities of color.'” Adams subsequently apologized, the Post noted.

With that one paragraph, the Post excluded the interpretation of the data that might suggest that differences in personal behavior might influence differences in the spread of, early detection of, and death from the virus. The analytical fix was in. The authors would accept only explanations that were variation on the structural racism theme.

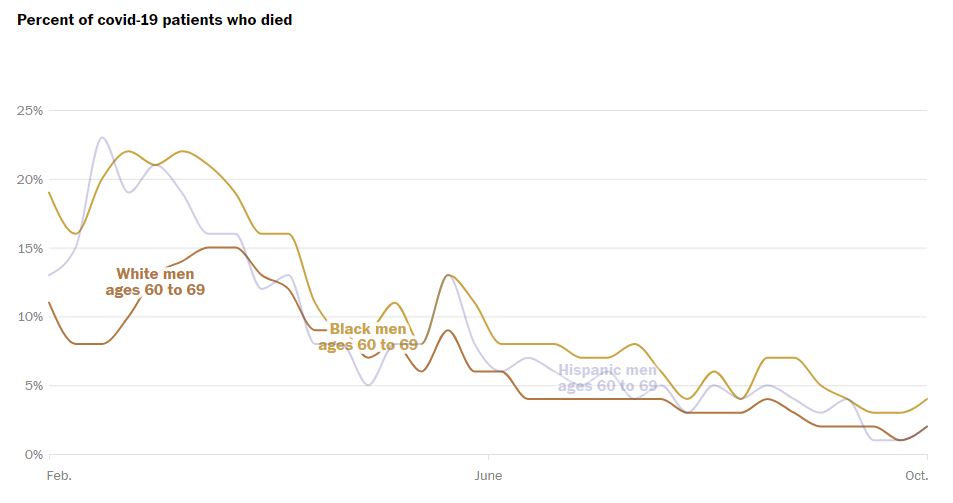

But the Post’s own data calls out for a different explanation. Look at the chart above, which compares the death rates for white and black men aged 60 to 69. The racial disparity in death rates was greatest in the early phase of the epidemic, February to March, and then declined sharply. In part the falling death rate for older black men (which tracked the trend for black women and younger blacks) reflected the society-wide decline in death rates for all racial categories as hospitals and doctors got better at treating the disease. But the gap narrowed as well.

What happened in the March/April tune frame that might account for the dramatic drop in the black death rate? Here are some clues.

On March 17, the actor Idris Elba went public with the fact that he had been infected by the virus. He used the occasion to dispel the “myth” that the virus didn’t affect black people. In a Twitter video, he said, “My people, black people, black people: Please, please understand that coronavirus …. you can get it, all right? There are so many stupid, ridiculous conspiracy theories about black people not being able to get it. That’s dump, stupid. … Stop sending out these stupid What’s App messages about black people not getting it. … Just know you have to be as vigilant as every other race.”

On April 7 Dr. Oluwatoyin, a Cook County infectious disease expert, held a press conference that was picked up by Club Chicago, an Internet publication. The rumor that black people are immune to COVID-19 was harmful, he said. “That kind of misinformation allows some of the infection to lay ground in the community.”

Appearing on CNN on April 10, basketball legend Magic Johnson compared COVID-19 to the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. HIV, he said, “was considered a white, gay man’s disease. People were wrong. Blacks thought that they couldn’t get HIV and AIDS. It’s the same thing as coronavirus. We were all wrong and the numbers switched from a white gay man’s disease to a minority disease, which it is today. The same thing here, misinformation went out in our community and said, oh, Blacks can’t get coronavirus and everybody’s been wrong about that, whoever’s been saying that in the black community. So that’s why we see these numbers so high. … We have to do a better job as African Americans to follow social distancing [and] stay at home.”

As established media began picking up the message, behaviors changed — reinforced no doubt by the real lived experience of African-Americans contracting the disease and heading to the hospital in large numbers. As blacks came to understand that they were as vulnerable to the epidemic as anyone, they took masking and social-distancing as seriously, if not more so, than other racial/ethnic groups. Disparities with whites shrank dramatically.

But you will read none of this in the Washington Post. The Post’s narrative attributes all health disparities to structural racism: either in the way healthcare is delivered or to underlying issues such as co-morbidities (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, etc.) that can be attributed indirectly to structural racism. Whether the refusal to consider other interpretations represents an unconscious paradigm from which Post writers and editors cannot break free or a conscious effort to suppress other points of view, I cannot say.

Either way, the intellectual bias is clear. The Post cherry picks the experts and facts that fit the narrative, dismisses experts and facts that don’t. Readers be warned: Never, ever, ever, accept anything the Post writes at face value. When writing about race in America, the Post always has an agenda. Always look for missing perspectives and missing context. Always dig deeper.