This report contains a correction.

Introduction and summary

The high price of child care has long been a burden for most families, rivaling the cost of college in many states and forcing families to make difficult decisions and trade-offs.1 However, this high price often fails to account for the actual costs that child care providers incur, and rarely, if ever, covers the “true” cost of care—that is, the cost to provide high-quality, developmentally appropriate, safe, and reliable child care staffed by a professionally compensated workforce.

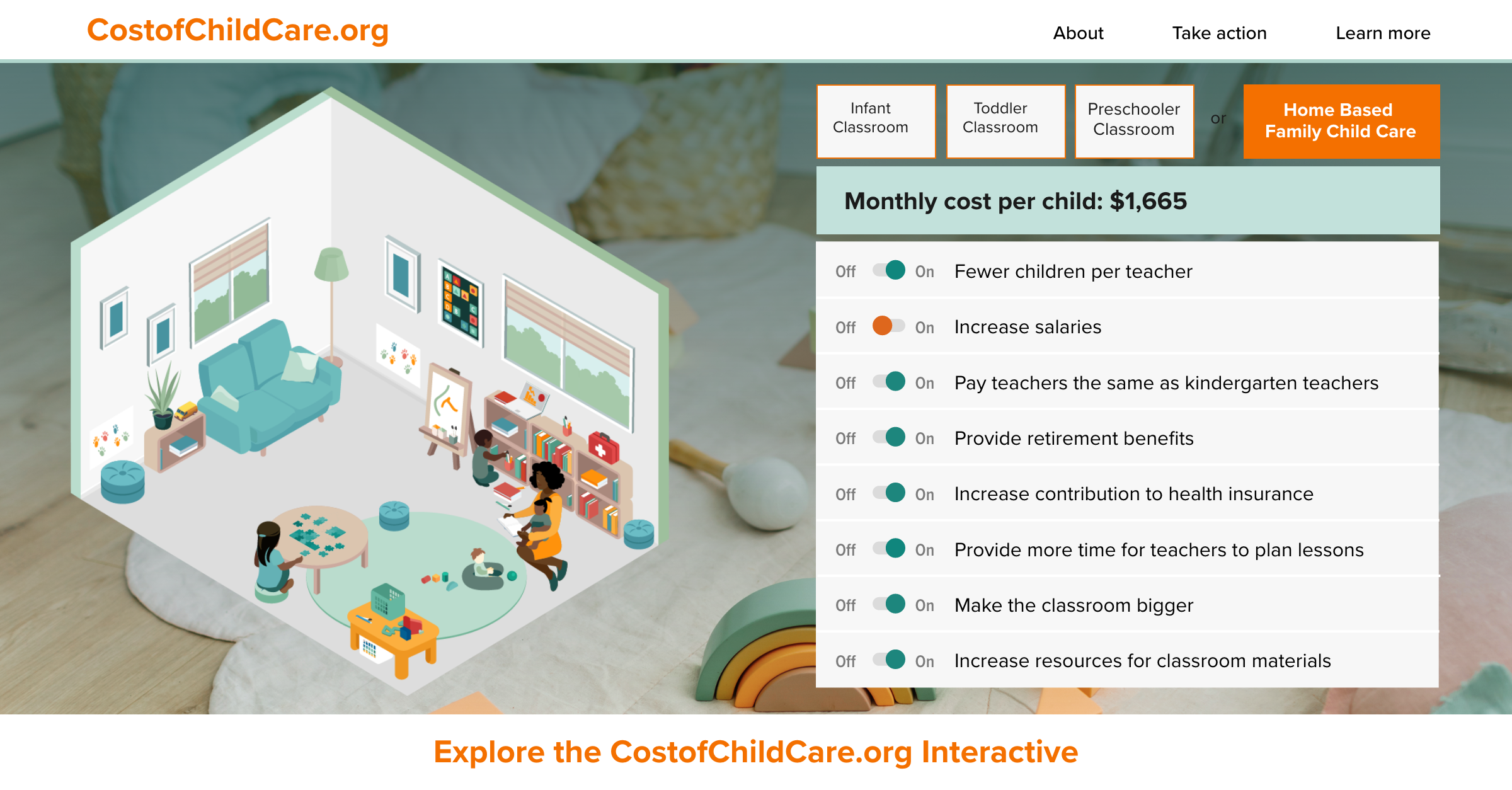

In 2018, the Center for American Progress developed an interactive cost estimation tool to illustrate the economics of child care, estimate the true cost of child care in each state, and better understand why high-quality child care is out of reach for many families.2 CAP is now releasing a refreshed version of this interactive, incorporating up-to-date data, adding several U.S. territories, and including the ability to estimate the cost of care in a family child care home setting.3 The updated interactive allows users to calculate the monthly cost of licensed child care at different ages and in different settings for each state or territory. In addition, as with the original tool, users can modify seven elements of the child care program—such as compensation levels and adult-child ratios—to better understand the impact of these variables on the cost of care.

Data from the interactive illustrate why increased public investment in child care is so necessary. On average, the true cost of licensed child care for an infant is 43 percent more than what providers can be reimbursed through the child care subsidy program and 42 percent more than the price programs currently charge families. To build and invest in a child care system that meets the needs of children, families, and the broader economy, is it critical for the federal government to provide funding at a level sufficient to cover the true cost.

The child care market is broken

Despite the critical role of child care in the economy, public funding to support widespread access is woefully inadequate. The primary public funding source for child care is the federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), authorized by the Child Care Development Block Grant Act, or CCDBG.4 This federal and state partnership program, which requires state matching funds, provides funds intended to help eligible families access child care through subsidy vouchers paid to the provider for an eligible child. However, the lack of funding means this program reaches only 1 in 7 eligible children, and many families who need support paying for child care do not meet the eligibility criteria.5 For example, a family of three with an annual income above $32,580 would not qualify for assistance in 13 states, according to an analysis from the National Women’s Law Center.6

In addition, the value of the subsidy—the amount that providers can receive for an enrolled subsidy-eligible child—is often insufficient to cover the true cost of operating a high-quality child care program. For a provider who can recoup the cost of care through parent tuition, there is no incentive to offer child care slots to subsidy-eligible families, severely limiting choice for families relying on this assistance to access child care. Although federal guidelines require states to set payment rates at a level intended to provide access to a majority of providers within the child care market, only one state, Maine, sets rates at the federally recommended level as of 2020—and even then, rates are still based on the broken market, which fails to account for true cost of care.7

This leaves the burden of paying for child care primarily on families who struggle to afford the true cost of care in most communities.8 Families are extremely price sensitive, with child care often taking up one-third or more of their monthly budget and forcing families to consider price above many other variables.9 While there is a high demand for child care in many communities, supply does not respond to that demand because families are already paying as much as they can afford, even though this amount rarely covers the true cost of operating the program. This is especially true for infant and toddler child care, where the gap between the true cost and what families can afford to pay is even greater, leading to a lower supply of child care for the youngest children.10 It is only in high-income communities—where families are most likely to pay an affordable threshold of their household income on child care11—that the traditional supply and demand market can work. When child care providers have adequate revenue, they can afford to invest in quality.12

The impact of this broken market falls heavily on the early childhood workforce. Early childhood teachers provide critical care and education, but this is not reflected in their compensation. The average child care worker in the United States earns less than $13 an hour and rarely receives benefits, leading to high turnover and a demoralized profession.13 The COVID-19 pandemic has only made it more difficult to attract workers to the child care sector.14 Research has shown time and time again that beyond the basic health and safety standards, the largest driver of quality in a child care program is the interactions between the caregiver and the child.15 The current child care market, with its broken fiscal model, fails to provide the investment necessary to pay early educators a fair wage or attract skilled workers to the field.

The impact of regulations on the cost of child care

Child care licensing regulations provide necessary safety protections such as employee background checks, safe sleep and CPR training, and group size limitations.16 Such regulations give families peace of mind that their children are being cared for in a safe environment with properly trained staff. In addition, many states have developed quality rating and improvement systems, or QRIS, which provide additional resources or incentives to providers that meet certain quality standards above the minimum licensing requirements.17 There is no evidence that these regulations are contributing to child care deserts18—places where families cannot meaningfully access care—or having a significant impact on the market price of child care.19

However, for already overstretched providers, meeting these requirements can present an additional budget strain that cannot be passed on to families given the challenges parents already face in covering the price of child care. In light of the importance of safe and developmentally appropriate care for child development, policymakers should look toward making investments that support providers in achieving the high standards that children deserve, rather than compromising on safety and quality.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many of the problems with how child care is funded. When K-12 school buildings closed early on during the pandemic, parents did not have to worry about whether those schools would eventually reopen. School districts continued to pay teachers because education funding is not dependent on whether the building is open or if families can pay a certain fee each month. For child care, on the other hand, the pandemic threatened the very existence of thousands of programs. With providers heavily reliant on parent fees—accounting for 52 percent of total industry revenue by some estimates20—the closure of entire programs or classrooms, the need for smaller group sizes to minimize the spread of the virus, and decreased enrollment as families chose to keep children at home had a dramatic effect. This decreased revenue, coupled with the increased costs of operating, left many providers unable to pay staff, forcing furloughs, layoffs, or closures.21 As vaccination rates increase and businesses reopen, families may soon find that the search for child care will become even tougher than it had been prepandemic.

Child care funding in the American Rescue Plan

In response to the unprecedented challenges facing the child care industry, the American Rescue Plan, signed by President Joe Biden in March 2021, made the single largest investment in child care the United States has ever seen.22 The bill allocated $39 billion to states and territories to support access to child care for essential workers during the pandemic and aimed to stabilize the industry so that child care remains available as parents and caregivers return to their physical work locations. While this funding was historic, it was intended only to stabilize the industry and ensure its survival through the pandemic. The data presented in this report make clear, however, that significant long-term public funding is required beyond the American Rescue Plan to ensure that families and children have continued access to high-quality child care, which allows parents to work and helps prepare children for kindergarten and beyond.

The true cost of child care is more than families can afford

The updated interactive, available at www.costofchildcare.org, includes the most recent data on child care workforce salaries and state licensing requirements. For the first time, it also integrates estimates for home-based family child care and data for several U.S. territories, allowing for a more robust analysis. Full data assumptions and sources are available in the accompanying methodology.23

Using data from the updated interactive, Figure 1 illustrates the average estimated monthly cost of child care in the United States for a child care center and a family child care home that meets state licensing standards. The cost of care for an infant is significantly higher than the cost for older children due to the smaller group size and adult-to-child ratios that are necessary for younger children. (Note: Family child care costs are not broken out by age due to the program operating as a single classroom serving multiple age groups of children.)

Figure 1

At just over $1,300 per month, families with infants would need to pay nearly $16,000 per year on average to cover the true cost of child care.

At just over $1,300 per month, families with infants would need to pay nearly $16,000 per year on average to cover the true cost of child care. Not only is this approximately 21 percent of the U.S. median income for a family of three, but it also comes at a time when families can least afford it.24

Estimating the true cost of family child care

Family child care (FCC) is an essential part of the early childhood system. FCC providers operate out of a residential home rather than a child care center and are a sought-after option for many families due to their small size; the mixed ages of children served; and the often flexible hours, including evenings and weekends, that many FCC providers offer. They are also often the only choice for families in rural areas without a critical mass of children to sustain a child care center.25 In this report, the term family child care provider refers only to licensed home-based providers and does not include family, friend, and neighbor child care, also known as FFN, or registered or license-exempt FCC homes.

While all licensed child care programs have their own unique characteristics, home-based FCC settings can vary significantly. Some operate as small centers, with an owner employing one or two teachers, while others are single-person businesses where the owner is the lead teacher as well as responsible for managing program operations. Operating out of a private home, the expenses a provider incurs can also vary significantly depending on how the provider manages their taxes and what other income they may have to cover monthly expenses.

Often, the market price of family child care is less than that of center-based care because the provider does not pay themselves a set salary. While this makes home-based child care an affordable option for many families, it is another example of a system that is built at the expense of the early childhood workforce. For FCC to be a sustainable part of the early childhood system—which is critical to promoting access for infants and toddlers, Black and Latinx families, and low-income families26—it is important to model the cost of providing home-based care that supports a fiscally sound program.

For the purposes of the interactive, the FCC model includes a salary for the owner/educator. This salary level is calculated at a commensurate hourly wage of a lead teacher in the equivalent center-based setting. The FCC provider salary is based on a 55-hour work week, reflecting that the provider is staffing the program alone and therefore must be present during any hours that the program is open, in addition to completing activities outside of the regular operating day. In this way, the model reflects the true cost of care—including the hourly wage the educator should make—rather than the current expenses incurred for most FCC providers. While actual costs will vary across programs, this approach provides a more realistic comparison with center-based cost and recognizes the expenses that FCC providers need to cover in order to be a sustainable part of the child care system.

Investing in higher-quality child care benefits the workforce

In addition to estimating the cost of a program meeting licensing standards, the interactive can also estimate the cost of a high-quality child care program that pays higher compensation, has lower teacher-child ratios, allows for more planning time for teachers, and provides a larger and better resourced learning environment. Table 1 provides results for each state and territory at a baseline of quality, or base quality, where the program meets minimum licensing standards, as well as for a high-quality scenario where all options in the interactive are selected.

Table 1

While the data in Table 1 demonstrate that high-quality child care costs significantly more than the current baseline, it is important to recognize where that additional funding goes. Using the underlying data from the interactive, it is possible to analyze the breakdown of expenses across five major categories. While the higher-quality scenario costs $1,073 more per month, Figure 2 illustrates that 84 percent, or $900, of this increase goes to the workforce through increased salary and benefits.

Figure 2

Where does your child care dollar go?

Parents who spend thousands of dollars each year on child care are often surprised to hear that their children’s teachers make poverty-level wages. However, analyzing child care providers’ budgets shows why this is the case.

Table 2 details a sample budget of an infant classroom in a hypothetical child care program, using data from the interactive. With parents paying $1,300 per month per child, providers have just under $82,000 available to cover salaries and benefits over the year. If the infant classroom is open from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., 10 hours a day, and has two teachers at all times, this translates into around $31 per hour to cover the salary and benefits of not only those two teachers but also the nonclassroom personnel who support program operations. This is inadequate to pay staff a living wage and illustrates that despite the high cost to families, the economics of child care mean that the teachers in this scenario are still likely to qualify for public assistance.

Current revenue streams do not cover the true cost of care

Each state conducts a survey of providers as part of the process for setting child care subsidy rates. The results of these surveys provide data on the current market prices charged to private-pay families. Comparing these data to the results from the cost of child care interactive at both the base-quality level and the higher-quality level shows that the market price of center-based infant child care does not cover the estimated true cost of care that meets base quality or licensing standards, let alone the cost of a higher-quality program, in any state. In FCC settings, the same holds true for all but one state. Table 3 presents the comparisons between the most recent market price data and the estimated cost of quality for each state. Table 4 makes the same comparison but for FCC homes.27

Tables 3 and 4 are available in the PDF, which can be found here.

Under CCDF requirements, states must set subsidy rates at a level that ensures equal access to the same services for children receiving a subsidy as those who are not receiving a subsidy. While equal access is not defined, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that states set rates at the 75th percentile of the most recent market rate.28 As of 2020, only the state of Maine sets rates at this level.29 Insufficient subsidy rates create a significant gap between the estimated cost of care and the amount providers can receive in reimbursement through the subsidy system, leaving programs that serve children who qualify for government assistance with limited funds to invest in program quality. Although there are significant variations across states, on average, subsidies cover only 75 percent of the cost of licensed care for an infant in a child care center and 66 percent of the cost in a family child care home. For high-quality child care, the subsidy covers, on average, only 42 percent of the cost for an infant in a child care center and 29 percent for an infant in an FCC home.

Table 5* is available in the PDF, which can be found here.

The broken fiscal model has a disproportionate impact on infants and toddlers and low-income communities

The current financing of the child care system is broken for providers trying to keep their doors open, parents struggling to pay for care, and educators scrambling to provide for their own families. However, the system has a disproportionate negative impact on the youngest children and children who live in low-income neighborhoods. Because child care subsidy rates in every state are based on market prices, the rates reflect the deficiencies of that local market. In a low-income neighborhood where families cannot afford expensive child care tuition, providers must set their rates low. However, this results in a low subsidy reimbursement rate, meaning that both the public and private revenues supporting the program are insufficient to invest in quality improvement efforts or pay skilled educators a living wage, much less recruit additional staff. Meanwhile, a program in a higher-income neighborhood that can set tuition rates higher receives a higher subsidy reimbursement for any eligible children that attend. Thus, current policies help providers maintain their level of quality but do nothing to assist struggling providers and those serving the most vulnerable children with funding to improve quality.

With strategic government support, states can address the deficiencies and unintended consequences of the current market and ensure equitable access to child care.

As the data in this analysis have shown, the true cost of infant care is significantly higher than the cost of care for preschool-age children. Parents struggle to afford the higher cost of infant care, especially when it comes on top of other expenses related to having a baby and lost wages due to the lack of access to comprehensive paid family and medical leave. While every state provides a higher reimbursement rate for infants compared with older children, Table 6 demonstrates that there remains a significant gap between how much more states pay for infants and how much more it actually costs. On average, across the United States, the cost of infant care is 49 percent higher than for a preschooler, but the average subsidy rate is only 26 percent more for an infant than a preschooler. As a result, child care providers often lose money when serving the youngest children. This in turn results in a far higher number of infant child care deserts—where the availability of child care is insufficient to meet demand—for children under 3 years of age, compared with the number of overall child care deserts for children from birth through age 5.30

Table 6

Providers can mitigate this impact by providing care to mixed age groups of children. The larger class sizes for preschoolers allow providers to balance their budget across the age groups. This reinforces the importance of a mixed-delivery approach to preschool policies. Successful preschool initiatives will allow families to access preschool in the setting of their choice, ensuring that all providers can benefit from the increased public investment for preschool age children.31

Conclusion

For too long, child care providers have barely been getting by, providing an essential service to children, families, and employers while simultaneously undervalued by a society that has not adequately invested in a critical piece of infrastructure for working families. A significant and ongoing public investment is needed to pay for the true cost of providing high-quality child care.

With strategic government support, states can address the deficiencies and unintended consequences of the current market and ensure equitable access to child care. All states should use additional public investment to set subsidy rates based on the true cost of care, rather than current market price. This increased investment will create better wages, a more stable educator workforce, and sustainable systems for children, families, and communities. Research has shown that this investment pays for itself several times over, with increased public investment in child care directly affecting maternal labor force participation,32 providing increased educational and socio-emotional benefits for children, and boosting pay and employment opportunities for the early childhood workforce.33

The government should also look to expand the number of families who receive help to pay for child care and ensure that they pay no more than 7 percent of their income on child care.34 Against the backdrop of the pandemic, with an increased recognition of the importance of early childhood education to children’s development and the importance of the child care industry to the economy, the federal government has an opportunity to realize this much needed investment and ensure that the child care system that emerges from the pandemic is stronger, more resilient, and better meets the needs of all children and families.

About the author

Simon Workman is the principal and co-founder of Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies and the former director of Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Laura Dallas McSorley for her thoughtful contributions to this report. They also thank Carson Bear, Mat Brady, Rosemary Cornelius, MK Falgout, Darya Nicol, Bill Rapp, Erin Robinson, and Elyse Wallnutt, who helped develop the interactive on which the data in this report are based.

* Correction, July 6, 2021: Table 5 of this report has been updated to reflect the annual family child care subsidy rates for each state.