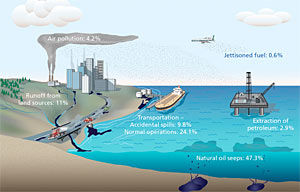

Because oil is not a single substance, scientists face a number of challenges when it enters an environment as complex as the ocean. Crude oil and many refined petroleum products are a complex mixture of hundreds of chemicals, each one with a distinct set of behaviors and potential effects when released into the marine environment. Some of these substances differ only in the location or orientation of a single carbon atom on a long molecular chain involving dozens of atoms. Despite this, even chemicals with nearly the same molecular structure can behave very differently once they enter the water, atmosphere, sediments, or an organism. As a result, scientists who study oil in marine settings often say that every spill is different and find that they must ask a unique set of questions every time they focus on a new location or event. Source Matters Oil can come from a variety of sources, each of which influences the amount, type, and duration of a spill. The 2003 report published by the National Research Council titled Oil in the Sea III organized these sources into four categories: natural seeps, petroleum extraction, petroleum transportation, and petroleum consumption. Of these, seeps are by far the single largest source, accounting for nearly half of all the petroleum compounds released to the ocean worldwide each year. Seeps are also the only natural source of oil input to the environment. The other sources, in order of magnitude, are extraction, transportation, and consumption and stem from human activity. An important difference between seeps and human-generated inputs is that seeps are widely distributed around the world and occur at a fairly slow and relatively constant rate. So constant, in fact, that some animals and microbes have evolved to thrive in the presence of the chemicals that flow from the seafloor near seeps. Studies of these unique organisms and ecosystems are an important part of the picture that scientists are assembling of how oil affects marine biology. Oil that enters the ocean as a result of extraction, transportation, or consumption often receives more attention than seeps for the simple fact that it is more visible. These events are of interest to scientists because they generally constitute large inputs from a single source and can occur anywhere in the world, often in places that have little, if any, natural ability to cope with the contamination. The impacts of oiling on individual plants and animals or on entire ecosystems range from the visible and immediate (e.g., smothering) to long-term and largely hidden (e.g., genetic disruption) and can have implications on the physical structure or health of a region for decades. Human systems, such as water supplies, fisheries, and tourism industries, are also vulnerable to oil spills, and this adds even more complexity when trying to understand the full effects of a particular event. Time is Key to Understanding Over time, the hydrocarbons that make up oil change once the enter the ocean. Some evaporate, some dissolve into the water column, some become buried in sediment or consumed by bacteria and animals. These processes are highly variable and depend on the composition, amount, and duration of a spill; its location and seasonal timing; as well as the nature of clean-up activities. Even regulatory and legal decisions can affect where oil ends up in the environment and what form it eventually takes. Science can help inform the decision-making process that ultimately influences the long-term fate of oil in the ocean, as well as the prospects for more spills to occur in the future. As the number in its name implies, Oil in the Sea III is part of an ongoing effort by scientists, including many at WHOI, to improve and expand understanding of the input, fate and effect of oil in the marine environment. Events that have been out of the news for generations are still the focus of intense research activity and strong debate among scientists because these events continue to affect the marine environment and society. This site attempts to assemble some of the work that WHOI scientists have contributed over the decades to answering the important question of what happens when oil enters the ocean. Last updated: May 2, 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||