Abstract

There are few psychosocial support programs specifically designed to meet the unique developmental and health needs of LGBTQ youth. Even when available, many youth face significant barriers to accessing LGBTQ-specific services for fear of being “outed” to parents, peers, and community members. The current study assessed the utility, feasibility, and acceptability of a synchronous, adult-facilitated, chat-based Internet community support program for LGBTQ youth aged 13–19. Chat transcripts were analyzed to examine how LGBTQ youth used the chat-based platform to connect with peers and trusted adults. A separate user satisfaction survey was collected to assess the personal (e.g., sexual orientation, gender identity, age) and contextual (e.g., geography, family environment) characteristics of youth engaging in the platform, their preferred topics of discussion, and their satisfaction with the program focus and facilitators. Qualitative data analysis demonstrated the degree to which LGBTQ youth were comfortable disclosing difficult and challenging situations with family, friends, and in their community and in seeking support from peers and facilitators online. Youth also used the platform to explore facets of sexual and gender identity/expression and self-acceptance. Overall, users were very satisfied with the platform, and participants accurately reflect the program’s desired populations for engagement (e.g., LGBTQ youth of color, LGBTQ youth in the South). Together, findings support the feasibility and acceptability of synchronous, adult-facilitated, chat-based Internet programs to connect and support LGBTQ youth, which encourage future research and innovation in service delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Studies consistently document health disparities for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ) youth in the United States (U.S.). These disparities are primarily attributed to stigma and discrimination (Fish et al., 2020a). LGBTQ youth experience poorer mental, behavioral, and sexual health than their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Russell & Fish, 2016; Saewyc, 2014). Despite a growing acceptance of LGBTQ youth and policy changes aimed at protecting them, studies suggest that disparities in mental health, substance use, and victimization have remained relatively stable over the past 15 years (Fish et al., 2019a, b; Poteat et al., 2020; Raifman et al., 2020). This persistence emphasizes the need for broader prevention and intervention efforts to address LGBTQ youth’s unique developmental and health needs.

Unfortunately, evidence-based programs supporting LGBTQ youths’ health, wellbeing, and positive development are limited and biased towards individual therapeutic and pharmacological treatment (Coulter et al., 2019; Fish, 2020). LGBTQ youth also experience barriers to community-based care (e.g., safety concerns, lack of competent providers). In contrast, LGBTQ youth are active users of Internet-enabled devices (e.g., smartphones). They are informally accessing resources and building community in Internet-based contexts—particularly if they are unable to access such opportunities in their day-to-day lives (GLSEN, 2013). Thus, Internet-based prevention and intervention programs may be particularly feasible for LGBTQ youth (Craig et al., 2015b; McInroy, 2020; Paceley et al., 2020). The emergence of digital interventions indicates the potential for evidence-based programming for LGBTQ youth delivered via Internet-enabled technologies (McInroy et al., 2019a). Given the prospective reach of Internet-based programming, the current study documents the development and delivery of a synchronous, adult-facilitated, chat-based community support program for LGBTQ youth called Q Chat Space. Specifically, we assess the utility, feasibility, and acceptability of Q Chat Space by examining youth engagement and experience with the program.

Minority Stress and Youth Resilience

LGBTQ health inequities are frequently conceptualized using the minority stress model (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017; Hendricks & Testa, 2012; Meyer, 2003). Minority stress illustrates how stigma and discrimination impact the day-to-day experiences of sexual and gender minorities; how interpersonal discrimination, internalized anti-LGBTQ stigma, and structural forces disenfranchise LGBTQ people and create stress that compromises their mental health, wellbeing, and coping strategies (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017; Meyer, 2003). Compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers, LGBTQ youth experience higher rates of bullying and peer harassment (Toomey & Russell, 2016), violence and victimization (Johns et al., 2018, 2019; Poteat et al., 2020), and family rejection (Ryan et al., 2009). These experiences contribute to LGBTQ youths’ poorer mental health (Fish et al., 2020a; Russell & Fish, 2016), higher rates of substance misuse (Goldbach et al., 2014), and sexual and reproductive health concerns (Saewyc, 2014).

Research on the experiences of LGBTQ youth has primarily focused on disparities and deficits in their health and social capital (Fish, 2020; Fish et al., 2020a). However, resilience is a core feature of the minority stress model (Meyer, 2015). Conceptualized as avoiding or productively adapting to risk exposure (Ungar, 2008), limited scholarship has applied resilience models to LGBTQ youth populations or explored mechanisms that foster resilience (Craig et al., 2015a; Ungar, 2008). Attention to normative and differential developmental processes of LGBTQ youth (see Coll et al., 1996) could help to identify pathways towards positive outcomes even in the context of stigma and risk (Ungar, 2008), given that many LGBTQ youth overcome (or never develop) mental health symptomology and substance use concerns (Craig et al., 2015a).

LGBTQ Youth and Participation in Internet-Based Communities

Although LGBTQ youth are more likely to experience cyberbullying and Internet-based harassment than heterosexual and cisgender youth (Abreu & Kenny, 2017), they do not perceive Internet-based contexts as riskier than in-person environments (e.g., schools, communities; GLSEN, 2013). LGBTQ youth use the Internet to explore and experiment with their sexual and gender identities and self-expression, develop affirming interpersonal relationships and community connections, and access identity-specific resources and services in contexts of relative safety and anonymity (Craig & McInroy, 2014; Craig et al., 2015a; Paceley et al., 2020). Experiences with stigma and isolation and a lack of in-person resources motivate LGBTQ youth to seek information and support via the Internet (Steinke et al., 2017). These activities potentially mitigate risk factors in their in-person environments (e.g., isolation, rejection), foster self-esteem and self-acceptance, and compensate for their difficulties accessing information and resources (Boyd, 2014; Craig & McInroy, 2014; Craig et al., 2015a).

Internet-based service provision may be appropriate and feasible for LGBTQ youth, indicated by the development and ongoing evaluation of a small but rapidly increasing number of digital programs designed for the population (McInroy, 2020). Significant opportunities exist for the continued development of evidence-informed, Internet-based programming for LGBTQ youth delivered in formats engaging and relevant to the population while adequately addressing safety concerns (McInroy et al., 2019a). This need for Internet-based services and programming is heightened in the current COVID-19 context, wherein LGBTQ youth are further removed from school and community services and confined to sometimes non-affirming home environments (Fish et al., 2020b; Paceley et al., in press).

The Current Study

The current study assessed the utility, feasibility, and acceptability of a synchronous, Internet-based, adult-led chat platform developed for LGBTQ youth called Q Chat Space. Using multiple data sources, we aimed to understand better how youth engaged and built community, motivations for participation, and satisfaction with the program. Findings contribute to the development and improvement of Internet-based services for LGBTQ youth. The study was also loosely rooted in the RE-AIM model, which guides researchers and practitioners to consider the implementation concepts of Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance in health behavior interventions (Glasgow et al., 1999). Given that the current study focused on the pilot phase of Q Chat Space, we primarily focused on reach (e.g., willingness of youth to engage, demographic differences between users and non-users) and potentials for effectiveness (e.g., evidence of youth community building and support).

Methods

Program Development and Pilot

Q Chat Space arose from intensive formative research (November–December 2014) exploring what LGBTQ youth wanted from an intervention (Steinke et al., 2017). Youth shared hesitancy with attending in-person groups and offered suggestions for digital programs. This research was used to develop the Q Chat Space program, a “digital community center” that translates “drop-in” peer support groups—a core service of brick-and-mortar LGBTQ community centers—for the digital space (Fish et al., 2019a, b). Q Chat Space was designed with significant input from rural LGBTQ youth, who are often under-resourced (Paceley, 2016), as well as Black and Latinx LGBTQ youth, who are more likely to encounter stigma and marginalization (Toomey et al., 2017). A synchronous chat platform emerged that allows youth (age 13–19) to join adult-facilitated, Internet-based support groups anonymously. Facilitators are staff from LGBTQ community centers around the United States (U.S.) and trained by CenterLink, the organization managing Q Chat Space. Youth continue to offer input through a youth advisory panel made up of predominantly Black, Latinx, and rural youth (now in its third cohort).

Initial feasibility testing for Q Chat Space was conducted with trained facilitators from an LGBTQ community center in the Northeastern U.S. from February–June 2018 (see Fig. 1 for the detailed timeline). Eighteen 60-min support groups were hosted with 16 youth. This initial test (1) assessed the utility of the digital platform and (2) refined the chat protocol (e.g., length of chats, times for chats). The pilot program started in July 2018 that included facilitators from a second LGBTQ center in the Southeastern U.S. and engaged youth who were not necessarily attending in-person services. Youth were made aware of the program through the pilot organizations’ typical communication channels (e.g., social media, websites, emails, and outreach to youth serving professionals in their area). In January 2019, a third LGBTQ center was added to provide chat sessions specifically addressing sexual health. The third center also promoted Q Chat Space throughout their service area in the Southeast using similar communication strategies. The pilot enabled further revision of the chat protocol, improvements to the facilitator training, and fidelity monitoring. The pilot ended in May 2019. When the program launched nationally, CenterLink asked LGBTQ community centers across the U.S. as well as other youth-serving organizations to share the program information through social media, emails, and outreach. CenterLink also conducted a paid marketing campaign on Instagram.

Q Chat Space program and study timeline. 1Steinke et al. (2017). 2Transcript data are from the program pilot

Two data sources were used for the current study: (1) chat transcripts from the program pilot (July 2018–May 2019) and (2) a user survey conducted February–March 2020 to understand the characteristics of youth engaged with the platform, their motivations for joining, and their satisfaction with the program. As Q Chat Space was not originally designed for assessment and evaluation, we cannot assess the degree to which pilot users are present in the survey data, and thus the degree to which the two samples overlap (see the “Limitations and Areas of Future Research” section for further discussion). The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board approved the research protocol for both projects.

Study 1: Q Chat Space Program Pilot Transcripts

Sample

We include all transcripts from the program’s pilot phase (see Fig. 1). Transcripts were downloaded from the Q Chat Space platform and anonymized following pilot completion. All youth who use Q Chat Space do so anonymously and create a username that is never linked to personal identifying information. Still, to ensure anonymity during the transcript review process, all usernames were changed to pseudonyms and any potentially identifying information shared by youth in the chats was redacted to further eliminate deductive disclosure. The pilot included 74 support groups/transcripts, 12 of which were sex education discussions; 86 youth joined chats a total of 245 times.

Q Chat Space Pilot Transcripts

Transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis, a descriptive qualitative method providing flexibility and rigor (Braun & Clark, 2006). These are not “traditional” interview transcripts but text-based chat conversations. As such, they include short statements, brief phrases, and emojis. Transcripts were cleaned, de-identified, and pseudonym coded. Next, four analysts read the transcripts to establish an understanding of content and structure. They then engaged in initial coding using Dedoose version 7.0.23 (Dedoose, 2016), which resulted in a list of approximately 100 codes. All authors discussed codes and related quotes, combined ones that were similar, and identified ten broad thematic categories of codes on Q Chat Space content. The team met weekly during the coding process and discussed any discrepancies and disagreements in coding until consensus was reached. Transcripts were re-read to identify platform processes (e.g., chat structure, flow, engagement) in addition to content to understand how the chat environment might offer unique user experiences. In this phase, four analysts wrote brief process memos about each chat. The memos included prompts for facilitator roles, youth engagement, and affective/emotive context. Process memos were then analyzed and discussed at a team meeting to identify two relevant process themes.

Study 2: Q Chat Space User Survey

Sample

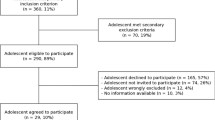

The survey design elicited information from three distinct user groups: (1) youth who created a program account but never attended a chat, (2) youth who attended one chat session, and (3) youth who attended multiple chat sessions. All youth who had engaged with the Q Chat Space platform (N = 2622) were sent a recruitment email for survey participation in exchange for entry into a raffle for one of sixty $25 gift cards. Of those invited, 291 youth participated. A waiver of parental consent was granted to ensure youth safety.

Measures

User type was assessed by asking, “How many times have you attended a Q Chat Space chat?” Those who registered but never attended were coded as “non-users,” and those who attended once or more than once were coded as “users.” Participants were asked to rank their motivation to sign up for Q Chat Space. Youth interest in chat topics was assessed differently across user groups. Non-users were asked what topics they would like for Q Chat Space to address; users were asked what topics they liked best. For both rank-order questions, responses were coded as top three = 1 and non-top three = 0.

Sociodemographic characteristics were collected at the beginning of the survey. Participants were asked to select the response that best represented their sexual and romantic orientation/identity (recoded: bisexual, monosexual, queer/pansexual, something else), transgender identity (recoded: no, yes, not sure), and race and ethnicity (Asian/Native/Other, Black, Hispanic, White, and multiracial recoded based on U.S. Census Bureau designation; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Participants indicated their age in years. Identity disclosure to parents was measured with two yes/no questions, one about sexual orientation and one about gender identity; these items were used to create a single variable of parental disclosure as yes to either question = 1 or no to both questions = 0. Self-reported zip codes were used to code region (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West; U.S. Census Bureau, 2019) and urbanicity, which was calculated using United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural–Urban Commuting Area Codes and corresponding metropolitan and nonmetropolitan designations (United States Department of Agriculture, 2020).

Family context and wellbeing measures included family acceptance and rejection; each was assessed with four items adapted from the Family Acceptance Project (Gamarel et al., 2020). Response options ranged from never = 0 to often = 3 (summed range 0–12; acceptance α = 0.86, rejection α = 0.88). Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler 6 (Ferro, 2019), which asked youth to report how often they felt a specific way (e.g., “nervous”) in the previous 30 days. Responses ranged from none of the time = 0 to all of the time = 4 (summed range 0–24; α = 0.88).

User satisfaction was assessed with two questions. One asked about chat topic satisfaction, and another asked about satisfaction with facilitators. Responses ranged from completely dissatisfied = 1, to completely satisfied = 5.

Analytic Procedures

Following preliminary descriptive analysis, chi-square tests of independence and independent sample t-tests were conducted to assess distinct features (if any) between users and non-users. Analyses were conducted using pairwise deletion. Thus, sample size varies across outcomes.

Results

Study 1: Program Pilot Transcripts: What Are Youth Talking About?

Coding resulted in twelve broad themes; ten related directly to chat content. Although some content categories overlap with facilitator-selected topics (see Supplemental Table 1 for a full list of chat topics), youth frequently identified their own topics or sub-topics of interest during sessions. Table 1 displays these categories and sample chat excerpts. Youth discussed the process of (1) coming out or disclosing their sexual and gender identities to others (e.g., family, peers) and experiences of being “outed” or “closeted.” Youth’s conversations related to (2) identity commonly addressed topics such as the use of labels and defining one’s sexuality and gender, as well as the process of questioning and exploring identity. When content related to (3) intersectionality arose in chats, it was common for youth to explore the intersections between ethno-racial and LGBTQ identities and seek greater understanding of the concept of intersectionality generally. Youth’s (4) family dynamics were a significant topic, as they thoughtfully explored supportive and unsupportive family relationships and experiences. Discussions of (5) LGBTQ community dynamics reflected similar significance and depth and included community strengths and challenges, such as chosen families and community-based conflict.

Another common topic was youth’s perceptions of (6) support, as they discussed supportive and unsupportive environments, as well as supportive and unsupportive adults. Youth also considered (7) direct or proximal stressors in their lives, describing encountering discrimination, dealing with identity-related stress, and other day-to-day challenges. Additionally, (8) indirect and structural stressors were commonly discussed, such as the political climate towards LGBTQ populations and the socio-cultural environment regarding LGBTQ people. Many chats focused on (9) media, as a formal topic of discussion or in a more informal way. Media consisted of both offline (e.g., television) and online (e.g., YouTube) sources. Discussions about media depictions of LGBTQ people and communities were prevalent. Finally, youth were candid about their (10) physical, mental, and sexual health experiences.

In addition to content themes, the process memos revealed two additional themes: (1) differences in chat structure and process and (2) the potential benefits of chat participation. The chats process, particularly the emotive quality, was directly related to the youth participants—which would also be expected in offline support groups. Chats could be filled with talkative, energetic, and excited youth, even when the emotive context was sad, scared, or confused. Other chats consisted of more withdrawn youth, who seemed nervous or less engaged. Some chats were very facilitator-driven in structure, indicated by the facilitators guiding the conversations. Others were youth-led, with youth directing the flow of the conversation. Some chats were educational (e.g., providing information on safer sex practices), and youth tended to ask questions and learn from the facilitators. In contrast, other chats were emotionally driven, such as those where youth discussed and shared experiences about rejecting or unsupportive families.

Process memos also revealed potential benefits of the Q Chat Space program, which provided youth with a space to share their thoughts and experiences and be validated and affirmed in their LGBTQ identities. Youth often engaged in strategies to build rapport, foster community, and support each other. They sought advice, provided mutual validation and reinforcement, asked follow-up questions, and offered resource suggestions. Sometimes, youth acted as peer mentors for one another—often witnessed when chats included both youth who were not out or newly out and youth who had been out and involved in the LGBTQ community for some time. Lastly, some chats provided educational information or resources from which youth seemed to benefit, although youth frequently reported greater benefits from the sense of community.

Study 2: Q Chat Space User Survey: Who’s Engaging and Why?

Table 2 displays sample characteristics and examined sociodemographic differences between users and non-users. Users and non-users did not differ in their sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, region, urbanicity, being out to parents, age, family rejection, family acceptance, or psychological distress. Users, however, were more likely than non-users to identify as gender diverse (X2 (2), 240) = 11.38, p < 0.01). Overall, users were very satisfied with chat topics (M = 4.19, 95% CI [4.00, 4.38]) and facilitators (M = 4.36, 95% CI [4.18, 4.54]). Chat topic and facilitator satisfaction did not vary by sociodemographic or contextual characteristics.

The most commonly cited motivations for joining Q Chat Space (see Table 3) were wanting to talk with other LGBTQ young people (71.06%), having a safe space to talk about LGBTQ identity (55.74%), wanting to connect with other youth from the same background (43.83%), and wanting to feel like part of the LGBTQ community (43.40%). Participants most commonly included emotional and mental health (43.72%), groups for trans/non-binary youth (33.37%), coming out (31.60%), and sex education (27.71%) in their most preferred chat topics.

Discussion

Despite an increase in Internet-based resources for LGBTQ youth, the developing evidence-base lacks synchronous, structured, or adult-facilitated programs (Lucassen et al., 2015; McInroy et al., 2019a). Guided by the constructs of reach and effectiveness from the RE-AIM model (Glasgow et al., 1999), we assessed the utility, feasibility, and acceptability of Q Chat Space—a synchronous, adult-facilitated, Internet-based program designed to address risk factors (e.g., isolation, rejection, stress) associated with the well-established mental and behavioral health needs of LGBTQ youth. Findings suggest that Q Chat Space is an acceptable and feasible program given its ability to reach and engage youth from across the U.S., and its effectiveness in providing a welcoming environment in which LGBTQ youth are motivated to engage and discuss topics relevant to their lives and health.

Since its inception in 2018, Q Chat Space has grown from one session per week to a robust Internet-based program offering twelve 90-min chat sessions weekly. Further evidence of reach is demonstrated in the continued scale-up of Q Chat Space: As of May 31, 2021, Q Chat Space has hosted 1035 groups with 2377 unique users and an average of 15.5 youth attending each chat. The user survey findings showed that among youth who attended at least one chat, the average number of attended chats was 5.42. Youth-reported high levels of satisfaction with the chat topics and facilitators (average > 4 on a scale of 1–5), which also support acceptability.

Nearly half (44%) of those who signed up for the program were youth of color, and a similar proportion (46%) were from the Southern U.S., suggesting that the program is engaging the intended population. Roughly 11% of youth who completed the user survey were from rural communities, which signals that Q Chat Space is accessible to LGBTQ youth in areas with historically limited services. Youth who attended at least one chat were also more likely to be transgender or gender diverse, which is consistent with youth engagement with in-person community programs (Fish et al., 2019a, b) and other Internet-mediated spaces (McInroy et al., 2019b).

Claims of acceptability, feasibility, and reach were further strengthened by minimal sociodemographic and contextual differences between users and non-users. This is particularly important with regard to characteristics that may inhibit access to in-person or voice-based services. For example, users and non-users did not differ on parental disclosure, family rejection, family acceptance, or psychological distress. Often, youth who are not out to their parents may hesitate to engage with in-person and Internet-based LGBTQ resources for fear that their parents will find out—this restricts youths’ access to supports and services (Paceley et al., 2020). The platform’s chat-based nature likely helps youth avoid concerns about family members accidentally overhearing their conversations in the same way they might if they were talking to friends (Fish et al., 2020b).

We also examined pilot program transcripts to explore the content and process of youth conversations. We identified ten content themes that suggest preliminary effectiveness in engaging youth in community-building and support: coming out, identity, intersectionality, family dynamics, LGBTQ community dynamics, support, direct or proximal stressors, indirect and structural stressors, media, and physical, mental, and sexual health. Findings highlight two important points. First, the chat conversations’ content is directly related to contexts and processes that impact youth mental and behavioral health, as outlined in the minority stress model and related empirical work (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017; Meyer, 2003). For example, family rejection (Ryan et al., 2009), peer harassment (Russell & Fish, 2016), and coming out stress (Baams et al., 2015) are implicated in LGBTQ youth mental health and substance use (Goldbach et al., 2014; Russell & Fish, 2016). Youth felt comfortable to discuss personal and stressful experiences in a context with peers and facilitators who could normalize these experiences, offer support, and recommend resources and information—reactions that could mitigate the negative impacts of these stressors (Wagaman et al., 2020). Results also suggest that youth may feel safer and more comfortable sharing personal or uncomfortable experiences and questions in a text-based (rather than face-to-face) context; youth mentioned how they were able to say what was on their mind, appreciating both the anonymity of the space and the presence of LGBTQ peers and supportive adults.

Second, youth from the user survey also noted that their three strongest motivations for signing up for Q Chat Space were to talk to other LGBTQ young people, find a safe space to talk about their LGBTQ identity, and connect with youth from the same background. These motivations emphasize the need to cultivate LGBTQ community connections. The themes identified in the transcript analysis align closely with these desires. Although LGBTQ community affiliation and support have been studied among adults (Frost et al., 2016), these experiences’ effects are less-often examined among youth. Some qualitative work has found that LGBTQ youth, particularly youth in rural areas, have a strong desire to connect with LGBTQ peers in safe and supportive environments but often face physical, structural, and emotional barriers in doing so (Paceley, 2016). Other work has shown that LGBTQ youth who engage with in-person LGBTQ community centers report better self-esteem and mental health, and lower substance use, than those who do not engage with these programs (Fish et al., 2019a, b). The ability to cultivate LGBTQ community in an Internet-based environment, particularly for those who cannot seek it elsewhere, is critical for LGBTQ youth health and wellbeing.

Limitations and Areas of Future Research

Limitations qualify our findings. First, this work is exploratory. Q Chat Space was not originally designed for assessment and evaluations. We are therefore not aware of how many of the pilot users are represented in our user survey, nor were we able to contact only those youth who participated in the pilot. Future studies with a priori benchmarks and rigorous data collection will provide better assessments of feasibility and acceptability. For this same reason, assessing the impact of the program on intermediate and long-term outcomes related to mental health among LGBTQ youth was not possible. It would be important to design studies able to capture the short- and long-term changes in mental and behavioral health as a result of the program. Second, the user survey was valuable for understanding who was engaging with the platform, their satisfaction with the program, and their motivations for joining. However, the user survey only reflects a subsample of youth who have registered and participated in the program. A comprehensive demographic survey during registration and tracking use over time would help evaluate the degree to which the program engaged the intended population and the diversity therein. Lastly, this evaluation’s ad hoc nature also precludes our ability to assess youth who opted not to enroll in the program. Tracking recruitment and enrollment efforts will allow for better assessments of feasibility and acceptability.

Implications

Our findings highlight the acceptability and feasibility of a synchronous, facilitator-led chat-based support program for LGBTQ youth. Importantly, the use of an Internet-based, textual program like Q Chat Space engages youth who may not have disclosed their LGBTQ status or who are fearful of being “outed” through the use of in-person or voice-based services. Obtaining community and resources via the Internet provides relative anonymity while simultaneously increasing accessibility and individual specificity. Thus, such programs provide a relatively low-cost strategy to support youth, particularly those who experience barriers to procuring LGBTQ-specific resources and support in their schools and communities (Fish et al., 2020b; McInroy et al., 2019a, b). Q Chat Space is also unique as an Internet-based preventive intervention program for LGBTQ youth as many Internet-based programs this population are crisis-focused interventions (e.g., TrevorLifeline, TrevorChat, Trans Lifeline; McInroy et al., 2019a).

Q Chat Space’s scale-up in mid-2019 was particularly timely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Within the first month of shutdowns, average attendance increased from 5 youth per chat to 13; the average number of new youth joining chats also doubled. Recent research from the Q Chat Space team suggests that this increase in users was accelerated by the isolation and mental health difficulties LGBTQ youth are experiencing as a result of the pandemic. The pandemic has separated them from their friends and offline sources of support, as well as, in some cases, has kept them at home with unsupportive families (Fish et al., 2020b). CenterLink was called upon to provide expert support as LGBTQ centers around the country rapidly transitioned their drop-in services to the Internet. Anecdotally, COVID-19 is likely to change the landscape of community-based LGBTQ service delivery permanently. Although in-person services will undoubtedly return, many youth-serving organizations supported by CenterLink have discussed maintaining Internet-based programming developed during the pandemic (personal communication).

Conclusion

There remains urgent need for LGBTQ youth programs that support positive youth development and wellbeing, particularly those that can reach youth who are unable to engage with in-person resources due to isolation or community climate. We explored the feasibility and acceptability of an Internet-based, adult-facilitated chat platform for LGBTQ youth to interact, build community, and access resources. Results suggest that this preventive intervention format offers promising strategies to address the risk factors implicated in LGBTQ youth health and wellbeing. Findings show that youth are comfortable engaging in discussions that allow them to process the unique stressors of being LGBTQ and foster resilience through support and community engagement. Future research is needed to understand better these programs’ impact on LGBTQ youth health and the strategies to deliver them best.

References

Abreu, R. L., & Kenny, M. C. (2017). Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1–17.

Baams, L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696.

Boyd, D. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. Yale University Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Coll, C. G., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., García, H. V., & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914.

Coulter, R. W. S., Egan, J. E., Kinsky, S., Friedman, M. R., Eckstrand, K. L., Frankeberger, J., Folb, B. L., Mair, C., Markovic, N., Silvestre, A., Stall, R., & Miller, E. (2019). Mental health, drug, and violence interventions for sexual/gender minorities: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 144(3), e20183367.

Craig, S. L., & McInroy, L. (2014). You can form a part of yourself online: The influence of new media on identity development and coming out for LGBTQ youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(1), 95–109.

Craig, S. L., McInroy, L., McCready, L. T., & Alaggia, R. (2015a). Media: A catalyst for resilience in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 12(3), 254–275.

Craig, S. L., McInroy, L. B., McCready, L. T., Di Cesare, D. M., & Pettaway, L. D. (2015b). Connecting without fear: Clinical implications of the consumption of information and communication technologies by sexual minority youth and young adults. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(2), 159–168.

Dedoose, V. 7.0.23. (2016). web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. www.dedoose.com

Ferro, M. A. (2019). The psychometric properties of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) in an epidemiological sample of Canadian youth. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(9), 647–657.

Fish, J. N. (2020). Future directions in understanding and addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth. The Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 49, 943–956.

Fish, J. N., Baams, L., & McGuire, J. K. (2020a). Sexual and gender minority mental health issues among children and youth. In E. D. Rothblum (Ed.), Oxford handbook of sexual and gender minority mental health (pp. 229–244). Oxford University Press.

Fish, J. N., McInroy, L. B., Paceley, M., Williams, N., Henderson, S., Levine, D., & Edsall, R. (2020b). “I’m kinda stuck at home with unsupportive parents right now”. LGBTQ youths’ experiences with COVID-19 and the importance of online support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67, 450–452.

Fish, J. N., Moody, R. L., Grossman, A. H., & Russell, S. T. (2019a). LGBTQ youth-serving community-based organizations: Who participates and what difference does it make? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(12), 2418–2431.

Fish, J. N., Turner, B., Phillips, G., & Russell, S. T. (2019b). Cigarette smoking disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Pediatrics, e20181671.

Frost, D. M., Meyer, I. H., & Schwartz, S. (2016). Social support networks among diverse sexual minority populations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 91–102.

Gamarel, K. E., Watson, R. J., Mouzoon, R., Wheldon, C. W., Fish, J. N., & Fleischer, N. L. (2020). Family rejection and cigarette smoking among sexual and gender minority Adolescents in the USA. International journal of behavioral medicine, 27(2), 179–187.

Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M., & Boles, S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM Framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1322–1327.

GLSEN, CiPHR, & CCRC. (2013). Out online: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth on the Internet. New York, NY: GLSEN. Retrieved 21 Apr 2017 from: http://glsen.org/sites/default/files/Out%20Online%20FINAL.pdf

Goldbach, J. T., & Gibbs, J. J. (2017). A developmentally informed adaptation of minority stress for sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 36–50.

Goldbach, J. T., Tanner-Smith, E. E., Bagwell, M., & Dunlap, S. (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363.

Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467.

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., McManus, T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., & Underwood, J. M. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67–71.

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Rasberry, C. N., Dunville, R., Robin, L., Pampati, S., Stone, D. M., & Mercer Kollar, L. M. (2018). Violence victimization, substance use, and suicide risk among sexual minority high school students—United States, 2015–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(43), 1211–1215.

Lucassen, M. F., Merry, S. N., Hatcher, S., & Frampton, C. M. (2015). Rainbow SPARX: A novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 203–216.

McInroy, L. B. (2020). Building connections and slaying basilisks: Fostering support, resilience, and positive adjustment for sexual and gender minority youth in online fandom communities. Information, Communication & Society, 23(13), 1874–1891.

McInroy, L. B., McCloskey, R. J., Craig, S. L., & Eaton, A. D. (2019a). LGBTQ youths’ community engagement and resource seeking online versus offline. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 37(4), 315–333.

McInroy, L. B., Craig, S. L., & Leung, V. W. (2019b). Platforms and patterns for practice: LGBTQ+ youths’ use of information and communication technologies. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36(5), 507–520.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213.

Paceley, M. S. (2016). Gender and sexual minority youth in nonmetropolitan communities: Individual- and community-level needs for support. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 97(2), 77–85.

Paceley, M. S., Goffnett, J., Sanders, L., & Gadd-Nelson, J. (2020). “Sometimes you get married on Facebook”: The use of social media among nonmetropolitan sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Homosexuality. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2020.1813508

Paceley, M. S., Okrey-Anderson, S., Fish, J. N, & McInroy, L. (in press). Beyond a shared experience: Queer and trans youth navigating COVID-19. Qualitative Social Work. Advanced online publication.

Poteat, V. P., Birkett, M., Turner, B., Wang, X., & Phillips, G. (2020). Changes in victimization risk and disparities for heterosexual and sexual minority youth: Trends from 2009 to 2017. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(2), 202–209.

Raifman, J., Charlton, B. M., Arrington-Sanders, R., Chan, P. A., Rusley, J., Mayer, K. H., Stein, M. D., Austin, S. B., & McConnell, M. (2020). Sexual orientation and suicide attempt disparities among US adolescents: 2009–2017. Pediatrics, 143(3), e20191658.

Russell, S. T., & Fish, J. N. (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 465–487.

Ryan, C., Huebner, D., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–352.

Saewyc, E. M. (2014). Adolescent pregnancy among lesbian, gay, and bisexual teens. In A. L. Cherry & M. E. Dillon (Eds.), International handbook of adolescent pregnancy: Medical, psychosocial, and public health responses (pp. 159–169). Springer.

Steinke, J., Root-Bowman, M., Estabrook, S., Levine, D. S., & Kantor, L. M. (2017). Meeting the needs of sexual and gender minority youth: formative research on potential digital health interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 541–548.

Toomey, R. B., & Russell, S. T. (2016). The role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization: A meta-analysis. Youth & Society, 48(2), 176–201.

Toomey, R. B., Huynh, V. W., Jones, S. K., Lee, S., & Revels-Macalinao, M. (2017). Sexual minority youth of color: A content analysis and critical review of the literature. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(1), 3–31.

Ungar, M. (2008). Putting resilience theory into action: Five principles for intervention. In L. Liebenberg & M. Ungar (Eds.), Resilience in action: Working with youth across cultures and contexts (pp. 17–36). Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

United States Department of Agriculture. (2020). Documentation: 2010 rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/documentation/

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). U.S. regions and divisions of the United States. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). About race. The United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

Wagaman, M. A., Watss, K. J., Lamnec, V., D'Souza, S. A., McInroy, L. B., Eaton, A. D., Craig, S. (2020). Managing stressors online and offline: LGBTQ+ youth in the Southern United States. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104799.

Acknowledgements

Foremost, we would like to acknowledge all of the youth participants of Q Chat Space and the dedicated facilitators and LGBTQ community centers that help support the Q Chat Space Program. We would also like to acknowledge the Wild Geese Foundation for supporting our feasibility phase and several anonymous donors who supported the pilot and national expansion of the Q Chat Space. We also recognize our broader team’s efforts in the collection and coding of the data: Hannah Tralka, Jillian Parisi, Judith Baron, and Rebecca Mann.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by the University of Maryland Prevention Research Center cooperative agreement U48DP006382 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Any interpretations and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and may not reflect those of the CDC. Fish also acknowledges support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant P2CHD041041, Maryland Population Research Center. Williams acknowledges support from the Southern Regional Education Board, the Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Research Scholars Program, and from the University of Maryland School of Public Health Gold Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Both studies referenced in this report were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review board in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from individual participants included in the Q Chat Satisfaction survey data collection. Chat transcripts were not originally conducted for the purposes of research and therefore did not obtain informed consent from participants; transcripts were designated as de-identified secondary data sources.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the CDC.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fish, J.N., Williams, N.D., McInroy, L.B. et al. Q Chat Space: Assessing the Feasibility and Acceptability of an Internet-Based Support Program for LGBTQ Youth. Prev Sci 23, 130–141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01291-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01291-y