MEET THE INTERNS p. 26 2022 ANNUAL CONFERENCE: CALL FOR PROPOSALS p. 08 ELECTION ENDORSEMENTS p. 10 SEPTEMBER 2021 • Vol 31.2

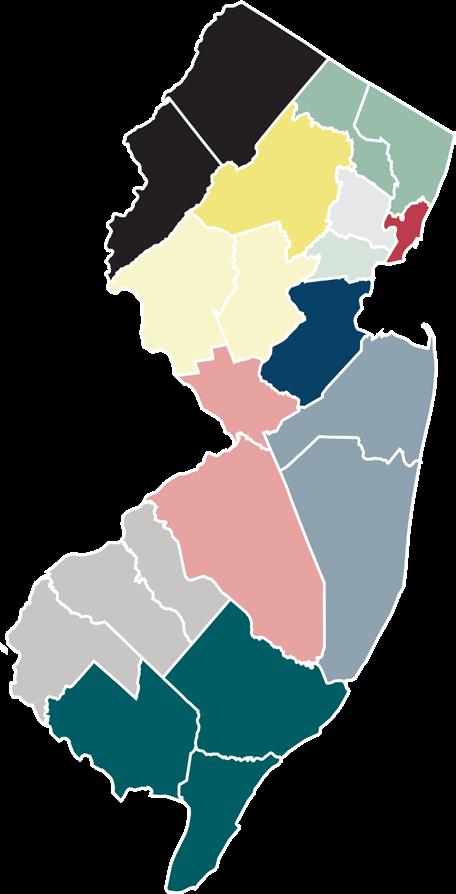

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

PRESIDENT, Widian Nicola

1 ST VICE PRESIDENT, Carrie Conger

SECRETARY, Ralph Cuseglio

NORTHEAST REGIONAL REP, Oninye Nnenji

SOUTHERN REGIONAL REP, Miriam Stern

ATLANTIC/CAPE MAY/CUMBERLAND CHAIR, Janelle Fleming

BERGEN/PASSAIC CHAIR, Melissa Donahue

CAMDEN/GLOUCESTER/SALEM CHAIR, OPEN

ESSEX CHAIR, OPEN

2 ND VICE PRESIDENT, Dawn Konrady

CENTRAL REGIONAL REP, Caelin McCallum

GRADUATE STUDENT REP, Hannah Loffman

UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT REP, Jack Serzan

NORTHWEST REGIONAL REP, Veronica Grysko-Sporer

UNIT LEADERS

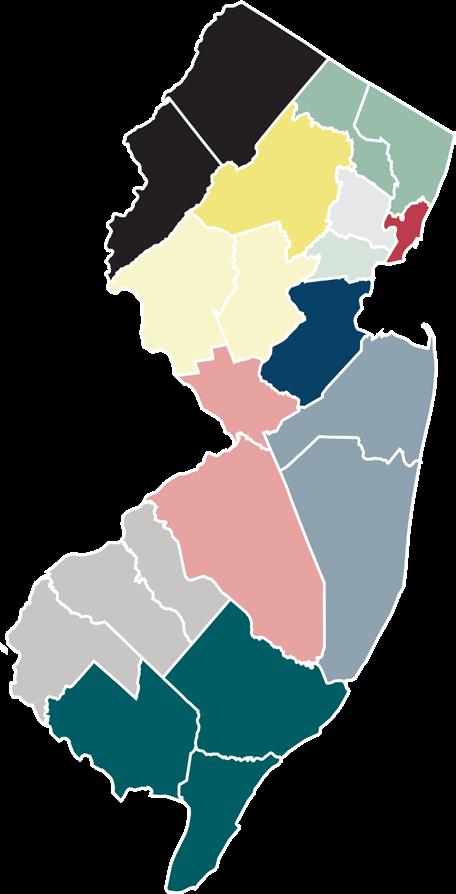

NASW-NJ has 12 units across the state of New Jersey.

HUDSON CHAIR, OPEN

MERCER/BURLINGTON CHAIR, Miguel Williams

CO-CHAIR, Michele Shropshire

MIDDLESEX

CHAIR, Tina Maschi

CO-CHAIR, Vimmi Surti

MONMOUTH/OCEAN CHAIR, Jeanne Koller

MORRIS CHAIR, Cheryl Cohen

CO-CHAIR, Veronica Grysko-Sporer

SOMERSET/HUNTERDON CHAIR, OPEN

SUSSEX/WARREN

CHAIR, Dina Morley

CO-CHAIR, Afifa Ansari

UNION

CHAIR, Hannah Korn-Heilner

CO-CHAIR Sarah Delicio

CHAPTER OFFICE

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Jennifer Thompson, MSW jthompson.naswnj@socialworkers.org or ext. 111

DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT & EDUCATION

Helen French hfrench.naswnj@socialworkers.org or ext. 122

DIRECTOR OF SPECIAL PROJECTS

Annie Siegel, MSW asiegel.naswnj@socialworkers.org or ext. 128

MEMBERSHIP AND EDUCATION SPECIALIST

Willis Williams

wwilliams.naswnj@socialworkers.org or ext. 110

DIRECTOR OF MEMBER SERVICES

Christina Mina, MSW cmina.naswnj@socialworkers.org or ext. 117

DIRECTOR OF ADVOCACY & COMMUNICATIONS

Jeff Feldman, MSW, LSW jfeldman.naswnj@socialworkers.org or ext. 114

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Katherine Girgenti kgirgenti.naswnj@socialworkers.org or ext. 129

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT

Jessica LaVecchia, NASM-CPT jlavecchia.naswnj@socialworkers.org

www.naswnj.org

NASW–NJ CHAPTER OFFICE 100 Somerset Corporate Blvd 2nd Floor, Bridgewater, NJ 08807, Ph: 732.296.8070,

FROM THE PRESIDENT AND EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

HIDDEN HISTORIES: GLORIA E. ANZALDÚA

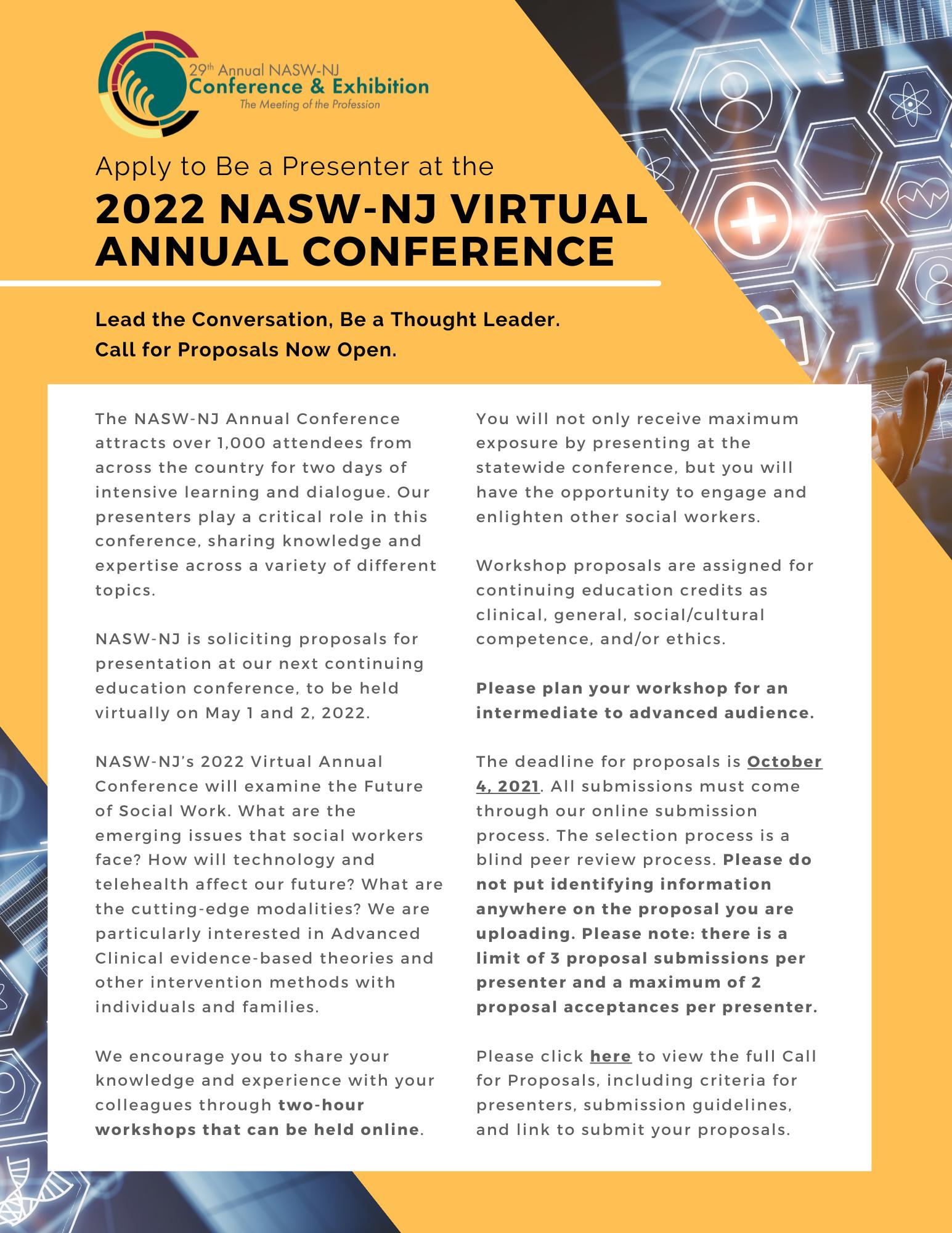

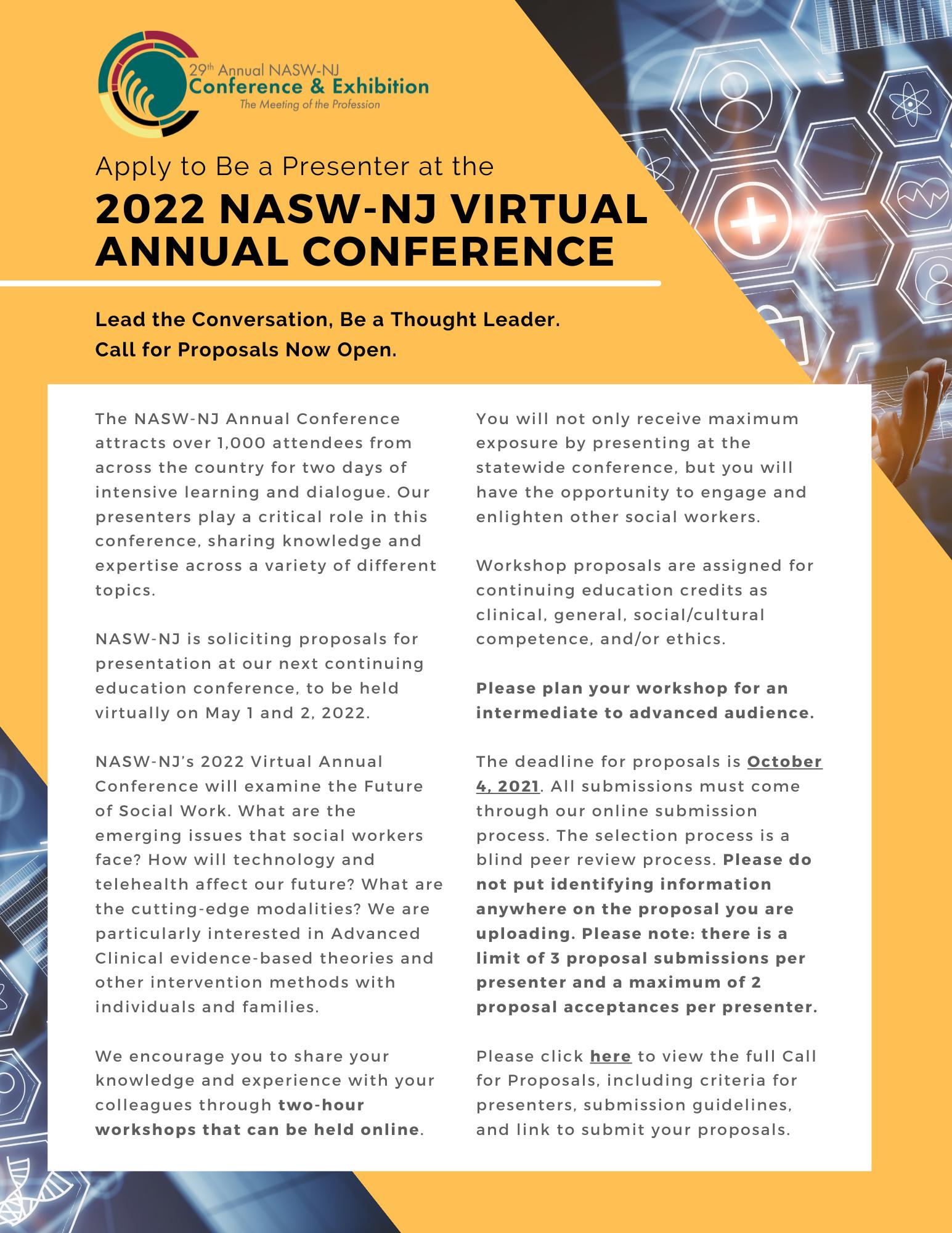

2022 ANNUAL CONFERENCE: CALL FOR PROPOSALS

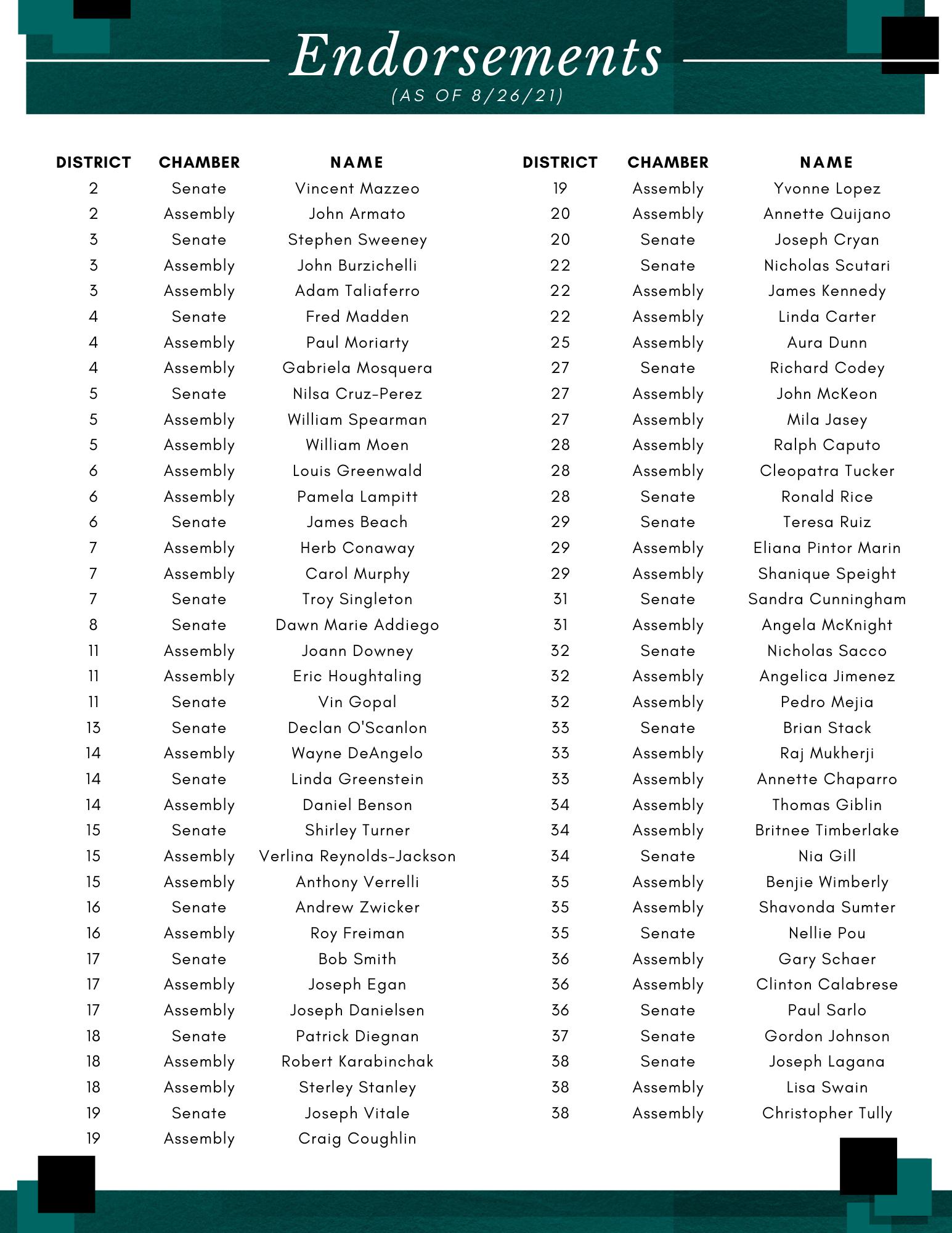

ELECTION 2021: NASW-NJ PACE CANDIDATES

ELECTION 2021: HOW TO GET INVOLVED

THE LATEST FROM THE FIELD

STUDENT CENTER

PARTNER SPOTLIGHT: NEWPORT HEALTHCARE

MEMBER CONNECT

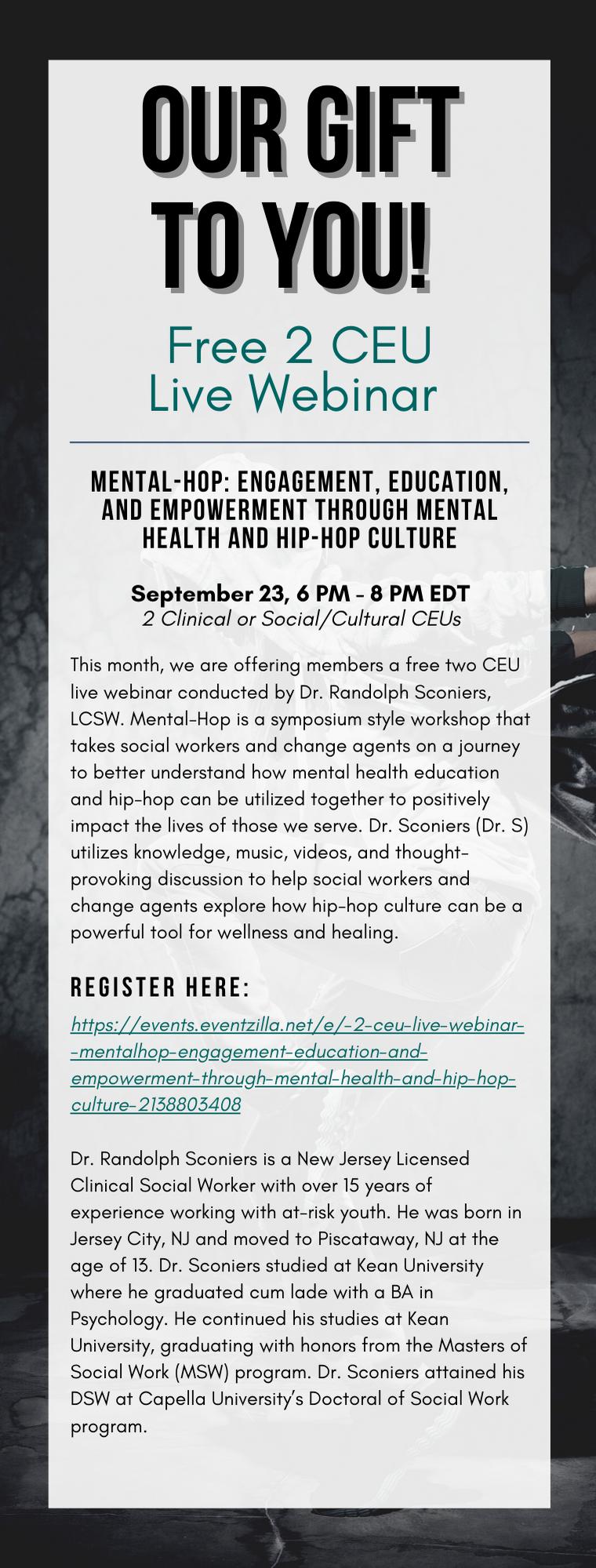

OUR GIFT TO YOU: FREE CEUS

MEMBER NEWS

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Special Note:

FOCUS will be taking a break in November. Instead, we’ll be releasing our Impact Report. Look for it in mid-November, mailed to you!

Thank you to our partner Rutgers School of Social Work for their support of NJ FOCUS

04 05 08 10 12 14 25 28 31 33 40 41

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FROM THE PRESIDENT & EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Friends and Colleagues,

We hope this month’s message finds you enjoying the last bits of summertime in New Jersey. This summer has been particularly interesting as we made strides to return to “normalcy” and have also seen a resurgence of COVID-19 in our communities, slowing our return and begging the question, “what does the future hold?”

The uncertainty can create anxiety and worry—a state that many have been living in since the onset of the pandemic. We feel that too, which makes it a difficult time to be a social worker.

Despite the ever-changing and growing demands placed on you, our colleagues right now—you continue to show up for our communities daily. You continue to work through policy changes that bring ambiguity to insurance and telehealth. You continue to show up to the licensing board meetings to advocate and demand more for the community. You continue to work through these challenges while managing your own questions and fears— worries about what might change tomorrow and how you’ll navigate that.

This coming year, we embark on a license renewal year—one of the most stressful times for our profession. What we know to be true is that having a plan can help ease some of that stress and anxiety. We have spent a lot of time speaking with you and assessing how we can best help you meet the licensing requirements for renewal. While we had hoped to return to an in-person Annual Conference, the optics are uncertain, and we have made the decision to host the 2022 conference virtually.

Amid this decision, we are excited to share that the 2022 NASW-NJ Virtual Annual Conference will be offered at a significant discount to our members. NASW-NJ members will have access to the online conference, and the opportunity to earn up to 20 CEU’s, for as little as $99.

While we are busy planning the conference, we anticipate that critical conversations will continue, and we look forward to bringing more advanced clinical workshops to foster those conversations. We invite our community of thought leaders to learn more about the proposal process and submit their proposals by October 4, 2021 here or see page 09 for more information.

We are hopeful that the virtual platform and the reduced cost to members will support your ability to schedule in advance and feel confident that the continuing education requirements will be met with ease.

This fall, NASW-NJ will continue to meet and gather virtually for Unit meetings and Shared Interest Groups. We look forward to meeting you where you are, supporting you, and continuing to advocate for the profession and those we serve during these unprecedented times.

Jennifer & Widian

Widian Nicola, DSW, LCSW PRESIDENT

Jennifer Thompson, MSW EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

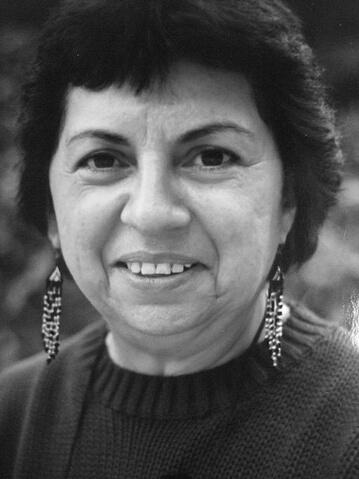

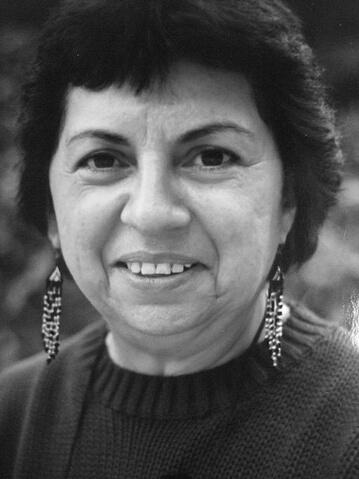

H i d d e n H i s t o r i e s :

Gloria E. Anzaldúa (1942-2004)

Recent discourse among the social work profession has focused on the “white washing” of social work history and education. Social work courses that discuss the history of social work often focus on the formative writings and work of individuals such as Jane Addams, Mary Richmond, Frances Perkins and other white social work luminaries. The website www. bestmswprograms.com features a list of “50 Notable Social Workers in U.S. History,” 42 of whom are white. 1 The Wikipedia page for “social work” mentions only two American social workers by name: Jane Addams and Mary Richmond. 2 A 2014 blog posted on the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work website cites the “9 Most Influential Women in the History of Social Work,” all of whom are white. 3 And a 2018 blog available on the Rutgers University School of Social Work website offers a list of “Influential Women in the History of Social Work.” 4 Of the 10 women listed, all but one, Dorothy Height, are white.

NJFOCUS • September 2021 | 5

U N C O V E R I N G T H E D I V E R S E R O O T S O F S O C I A L W O R K

Photo: Kendall, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons. Cropped, no saturation.

Over the next years’ worth of FOCUS issues, we’ll be digging deeper into the historical archives (thank you internet!), beyond the usually cited names, to bring to light the stories of lesser known individuals, primarily persons of color, who have helped move the profession of social work forward, as well as society as a whole. This series of articles does not intend to deny the contributions of commonly cited, white individuals to the profession of social work, but rather is intended to raise awareness and create discussion about how we think of social work history and the development of the profession in the U.S.

taught a course at UT-Austin called “La Mujer Chicana.” She said that teaching the class was a turning point for her, connecting her to the queer community, writing, and feminism.15

In 1977 she moved to California where she supported herself through her writing, lectures, and occasionally teaching courses in feminism, Chicano studies, or creative writing.16 She continued to participate in political activism, consciousness-raising, and groups such as the Feminist Writers Guild. She also looked for ways to build a multicultural, inclusive feminist movement.

While not a social worker by education or trade, Gloria E. Anzaldúa—a self-described “chicana dyke-feminist, tejana patlache poet, writer, and cultural theorist"—was a guiding force in defining the contemporary Chicano/ Chicana movement and a leader in lesbian and queer theory and identity.5,6 Her writings blended styles, cultures, and languages—weaving together poetry, prose, theory, autobiography, and experimental narratives.7

She engaged in complex theorizations regarding identity, subjectivity, epistemology, embodiment, politics, spirituality, and social transformation. Her work has been pivotal for the development of Chicana/o Studies and has had a significant impact in the fields of queer studies, disability studies, women’s and gender studies, Chicana feminism, and critical race theory.8

Anzaldúa was born in 1942 to Spanish American and Native American sharecropper/field-worker parents in the South Texas Rio Grande Valley. At age 11, her family moved to the city of Hargill, Texas on the U.S. Mexico border, at which point she entered the fields to work with her parents and siblings.9,10 As a teen, she began to experiment with writing and gain awareness of social justice issues.11 Anzaldúa’s father died when she was 14. His death meant that she was obligated financially to continue working the family fields throughout her high school and college years, while still finding time to pursue her interests in reading, writing, and drawing.12

Anzaldúa received her Bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Texas-Pan American in 1969 and a Master’s degree in English and Education from the University of Texas at Austin in 1972.13 In her 20’s, she worked as a teacher and instructed a wide variety of students. She first taught in a bilingual preschool program, then in a Special Education program for students with mental and emotional challenges.14 Later in the 1970s, she

Throughout the 1980s, Anzaldúa continued to write, teach, and travel to workshops and speaking engagements. However, her relationship with academia was tense, marked by a constant struggle to legitimize her chosen topics of study, methods, and writing style. She was famously unwilling to conform to Western academic standards through her signature use of code-switching, the resignification of indigenous symbolism, and her engagement with spirituality in serious theoretical terms.

She is perhaps best known for co-editing This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) Cherri Moraga, a groundbreaking anthology of poetry, fiction and essays by women of color. The collection confronted the racism and classism inherent in feminist thinking at the time. It is also noteworthy for fully embracing lesbian voices and concerns and making a clear case that feminism should be inclusionary. It marked an important intervention in feminist studies by bringing in different subjectivities and experiences and is considered pivotal in the development of Third World feminism.20, 21

Her semi-autobiographical book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), explored the borders between countries, languages, genders, the classes, and even within oneself. She also edited the follow-up volume to This Bridge Called My Back—Making Face: Making Soul/Hacienda

Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Women of Color (1990)—which included writings by famous feminists such as Audre Lorde and Joy Harjo.22, 23

In 2002, Anzaldúa co-edited another anthology, this time with AnaLouise Keating, entitled this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation (lack of capitalization intentional).24 Through personal narratives, theoretical essays, textual collage, poetry, letters, artwork and fiction, this bridge we call home examines and extends the discussion of issues at the center of her previous anthologies, such

6 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

as classism, homophobia, racism, identity politics, and community building, while exploring the additional issues of third wave feminism, Native sovereignty, lesbian pregnancy and mothering, transgendered issues, ArabAmerican stereotyping, Jewish identities, spiritual activism, and surviving academia. Written by women and men— both of color and white, from both inside and outside the United States—and motivated by a desire for social justice, this bridge we call home invites feminists of all colors and genders to develop new forms of transcultural dialogues, practices, and alliances.25

Anzaldúa was an avid observer of art and spirituality and brought these influences to her writing, as well. She taught throughout her life and worked on a doctoral dissertation, which she was unable to finish due to health complications and professional demands. She was later awarded a

17https://www.thoughtco.com/gloria-anzaldua-3529033

18 ibid

19https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo9780190221911-0086.xml

20 https://globalsocialtheory.org/thinkers/anzaldua-gloria-evangelina/

21https://www.thoughtco.com/gloria-anzaldua-3529033

22https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/gloria-e-anzaldua

23https://www.thoughtco.com/gloria-anzaldua-3529033

24https://globalsocialtheory.org/thinkers/anzaldua-gloria-evangelina/

25https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/52389.This_Bridge_We_Call_Home

26https://www.thoughtco.com/gloria-anzaldua-3529033

27https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo9780190221911-0086.xml

THE LATEST FROM THE FIELD

M E M B E R M I S S I V E S

“To thine own self be true.” In Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet, Polonius imparted those words to his son, Laertes, as he was preparing to leave for college as a reminder that there will be much required of him but not to forget who he was.

What does this have to do with social work? I am glad you asked! As a social work educator, we are charged with teaching students how to be effective social workers, while we face our own challenges that may impede that process. As a Black female social work educator, I will admit to you, it has been hard! During a time of racial reckoning in the world, the expectation is to carry out our charge, but we tend to neglect ourselves in the process.

May 25, 2020, was a normal day, surviving COVID-19, working from home, and quarantining at home with my family. Breaking news—George Floyd was murdered in Minnesota! We watched nine and a half minutes of horror on social media and the news. Unbeknownst to us, our children had come in and were watching it too. My daughter (who was 7 at the time) began to cry inconsolably. She could not believe what she saw and began to sob asking “why are they doing this to him? Why are they treating Black people this way?” I froze, I was speechless. The professor who specializes in race, racism, and cultural humility; the therapist who works with clients on coping with trauma; the speaker who travels to conferences to present to other social workers, doctors, nurses, etc. about

To Thine Own Self Be True: A Social Work Educator’s Response to Racial Trauma

by

by

racial healing—yet I had no words for my own seven-year-old daughter. Why? Because I was trying to process what I viewed. I could not unpack it for her because I could not do so for myself. So, I did what any parent would do, I held her in my arms, and we cried together. We talked about this situation and the countless others, but my daughters wanted to act. We found a local protest, made signs, and marched together as a family in solidarity.

In addition to my personal struggle, I was teaching a summer course. Our school was holding forums for students and faculty to share their emotions and feelings on the situation. My class asked to hold a special class meeting on the situation to discuss what to do. I obliged but gave a full disclosure at the beginning of class: " I am angry and do not have a lot to add at this moment. " My students understood, they shared, and I shared some action steps they could take to become more self-aware and what they could do to act. I declined an opportunity to facilitate a forum with students because I was still trying to process my feelings and did not want to deal with comments such as ‘why are you destroying your own city? Rioting and looting is not helping, he had substances in his system, all lives matter, etc.’

However, as we all know, George Floyd was not the first and certainly not the last. We have been here countless times but as an educator it hit differently this time. I thought of my father, husband, son, uncles, cousins, any Black male in

NJFOCUS • September 2021 | 15

Academia

“During a time of racial reckoning in the world, the expectation is to carry out our charge, but we tend to neglect ourselves in the process.”

Natalie Moore-Bembry, Ed.D., MSW, LSW

my life; this could have been them. I felt myself in a despair, but I knew I could not stay in that place long. The societal expectation is to shake it off—to keep working, teaching, parenting, and just keep going. But there is a moment when we all need to stop and assess who we are, where we are, and what we are doing. I am not talking about an occasional assessment but a continual one. My assessment included my ability to balance my hurt and pain with my responsibilities, to release the fear of publicly processing, and to recognize that my authenticity will be painful; I had to be me.

This may seem contrary to being a social worker and educator, but it is a day in my life. If I had not taken the moment to assess myself and walk my talk

of cultural humility and out of cognitive dissonance, I could have stagnated growth in myself and others.

For my Black colleagues, I see you, I hear you, and I am with you. For those who are our allies (not performative allies), I ask you to check on your Black colleagues. Every day we, Black social workers, put on a happy face and do a job that we love that may not love us back. We push for equality and equity as practitioners but rarely see it for ourselves. We care for the feelings of others and neglect our own. There must be a change, we cannot do it alone. Join me on this journey “to thine own self be true.”

About the Author:

Dr. Natalie Moore-Bembry is an Assistant Professor and Assistant Director of Student Affairs at Rutgers University School of Social Work. She teaches in both the graduate and undergraduate programs at Rutgers University and serves as an adjunct at St. Joseph’s College of Maine and Delaware State University. Her research interests are cultural humility, self-awareness, racism and oppression, and community organizing.

16 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

Academia

"Role" Call for Representation: More Black Clinicians Needed in Child Welfare

by Shonnell Flournoy

by Shonnell Flournoy

Child welfare involved Black youth and families need clinicians who can foster a kindred connection grounded in the esoteric Black experience.

Imagine being at the most vulnerable moment in your life and not having the opportunity to provide for your family. This was the reality for over six million Black Americans who believed they could escape the confinements of the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws in the South. The Great Migration north for Black families between 19161970 was a dream of prosperity.

However, this was not the case for far too many Black families. Instead, life in the rioting streets of Detroit, Chicago, and New York mirrored the oppression they were attempting to flee. To put it plainly, they had traded their pigsties for the projects. Drug production, criminality, prostitution, and the breakdown of Back families, combined with a lack of educational options in communities of color, allowed Black migrants to live, as Stevie Wonder said, “just enough for the city.”

One example of policy and practice that led to the deterioration of Black families was the “Man in the House” rule. These guidelines were intended to further societal (predominantly White) norms regarding who was morally deserving of welfare aid. 1 Government policy makers felt that if a natural parent—generally a woman—had a continuous sexual relationship with someone of the opposite sex, that person would serve as a substitute father, making the family ineligible for welfare payments. 2 It made no difference whether this individual was legally bound to support the children; it also made no difference whether he contributed to their support. 3 Specifically, the rules prevented adult

males from residing with mothers and children receiving governmental assistance. 4 This dynamic was played out for large audiences in the 1974 movie, Claudine , starring Diahann Carrol and James Earl Jones.

Sixty plus years later, reverberations from these policies and actions are still felt. Black families have been decimated. As of January 2021, Black children made up 33 percent of kids in foster care in New Jersey, despite comprising only 15 percent of the child population. 5 These youth also remain in foster care longer than their white and Latinx counterparts. 6

New Jersey Department of Children & Families (DCF) Commissioner, Christine Norbut Beyer (a social worker), has been steadfast in her pursuit to address the racial disproportionately and disparities in our state’s child welfare system. The Race Equity Steering Committee, developed by the Division of Child Protection & Permanency (DCP&P) within DCF, has their focus on several policies and practices designed to address racial equity. The most significant areas of interest, as related to the federal Adoption & Safe Families Act (ASFA) timeline, are resource, contracting, and prevention.

The question of whether DCF’s contracts inhibit or support race equity with families the agency serves is essential in preventing family separation and keeping families together. This includes efforts to contract with Black clinicians—psychologists, social workers, and therapists—who not only understand

NJFOCUS • September 2021 | 17

Child Welfare

but have shared the lived experiences of Black child welfare involved youth.

Two primary ways humans consciously process and move through their world are through the senses of sight and sound. Black individuals are regularly confronted with sights and sounds that are cognitively dissonant with their experiences— along with overt and covert messaging that their experiences are invalid or wrong. These perceptions are often met with indifference by non-Blacks around them, resulting in conscious and unconscious treatment of Blacks that replace human values and experiences with racial tropes and stereotypes.

Put simply, there is a need for clinicians who have similar backgrounds, up-bringing, and lived experiences with the systems that impact child welfare involved Black youth and families—from child welfare to social services to corrections and others. They need clinicians who can foster a kindred connection with families that is grounded in the esoteric Black experience. Walmsley notes, Black therapists are social representatives for Black American clients because they can “establish a consensual order, build communication, and provide a code with their [Black] clients for social exchange.” 9 Such therapists are able to help youth and their families process the divergent realities of societal expectations, as compared to the actual lived experiences of these youth and families. Because honestly, how can you put someone on the street called straight if you’ve never been to their house?

References:

1 Goldsmith C.F., Jr., Social Welfare -- The "Man in the House" Returns to Stay, 47 N.C. L. Rev. 228 (1968). Available at: http:// scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol47/iss1/19

2 ibid

3 ibid

4 ibid

As such, a key component to bringing racial consonance to the experiences of Black youth in the child welfare system involves increasing the number of Black clinicians who are contracted to work with these youth. We know representation matters, and Moscovici’s Social Representation Theory bears this out. This theory centers the professional's practice thoughts and behaviors within political, organizational, and legal systems, while simultaneously demanding recognition of the professional's consciousness—implying their ideas, personal experiences, values, and commonsense play a role in their decision making. 7

But we know commonsense is not, in fact, common. What is considered commonsense within many Black communities is minimized and considered aberrant by much of broader society. The “Godfather of Black Psychology,” Joseph L. White, declared Black psychology to be “the ability to connect, explain, organize, and facilitate the understanding of the cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and spiritual behavior of Africandescended peoples.” 8 To do so requires more than just a therapist with a complexion connection.

5 Livio, S. K. (2021, January 27). Child Welfare agency found ways to protect vulnerable kids in N.J. last year despite pandemic, monitor says. Available at: https://www.nj.com/politics/2021/01/child-welfare-agencyfound-ways-to-protect-vulnerable-kids-in-nj-last-year-despite-pandemicmonitor-says.html

6 N.J. Department of Children and Families. (n.d.). DCF Race Equity. https://www.nj.gov/dcf/equity.html

7 Walmsley, C. (2004). Social Representations and the Study of Professional Practice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690400300404

8 Defreitis, S.C. (2019). African American Psychology: A Positive Psychology Perspective. https://connect.springerpub.com/highwire_ display/entity_view/node/116243/content_details

9 Walmsley, C. (2004). Social Representations and the Study of Professional Practice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690400300404

About the Author:

Shonnell Flournoy is a Family Supervisor Specialist at the Department of Child Protection and Permanency for the State of New Jersey. She holds a Master’s degree in Public Administration and is pursuing her MSW at Monmouth University.

18 | NJFOCUS • September 2021 Child Welfare

The Influence of Race in Domestic Violence Services

by Ana I. Diaz Lopez, MA, MSW, LSW

As a social work professional in the field of trauma and abuse, my work for the last eight years has been largely with survivors of domestic violence from disenfranchised and marginalized communities. My fluency in Spanish has granted me the privilege to work with Latinx identifying survivors who bring histories of cultural trauma and oppression along with their experiences of domestic violence. While domestic violence occurs across all racial and ethnic groups, there are distinct differences in help seeking behaviors, access, and engagement in services for survivors from historically marginalized and oppressed populations. For these survivors, systemic oppression compounds with the complex issue of domestic violence creating barriers that limit access to safety and healing.

Take Claudia’s story for example. Claudia (not her real name), a 23-year-old Spanish speaking Latina sought services from her local domestic violence organization after seeing a flyer at her local supermarket. Claudia shared with her advocate that she was fearful because her husband had threatened to expose her immigration status if she left the relationship. She had no friends or family in the United States and had no idea where to turn for help. She was terrified of the police and worried they would arrest her because of her immigration status. Even though the abuse was worsening, Claudia shared that separation and divorce were not

options, as they would bring shame to her family. In Claudia’s case, factors of race, ethnicity, and immigration status intersected with her experience of domestic violence. Claudia’s ability and willingness to seek and engage in services was very much dependent on her cultural norms and experiences of oppression as a Latina. The social worker supporting Claudia was therefore tasked with taking a step back to view the way in which these intersecting factors came together to form Claudia’s story. By responding with cultural responsiveness and humility the advocate was able to begin to help Claudia explore her options and plan for safety.

As social workers it is crucial that we recognize and remain willing and able to address the intersections of race and oppression when engaging with survivors from marginalized communities. Failing to do so can lead us to miss important opportunities for connection, cause us to alienate the survivor, or lead us to offer solutions that are ineffective and even potentially harmful.

It is important to recognize the strategies and tools in our “tool box” may not apply uniformly to each survivor. The “safety plan,” for example, a commonly used tool in domestic violence work, intended to aid the survivor in planning for safety, must be individualized in order to be effective. Well-intentioned advocates often suggest survivors

NJFOCUS • September 2021 | 19

“As social workers it is crucial that we recognize and remain willing and able to address the intersections of race and oppression when engaging with survivors from marginalized communities.”

Domestic

Violence

include law enforcement and the court system in their safety plans. While it may seem these two entities belong on a safety plan, for survivors from communities of color, police and other law enforcement personnel may pose additional threats to safety or be associated with very real and very negative experiences of personal and community trauma and violence. In order to holistically, humbly, and effectively support a survivor it is important for social workers to remain mindful and sensitive to the cultural experiences of those they are working with.

When a survivor of gender-based violence walks through our door, they don’t only bring the trauma of the abuse they’ve experienced with them. They bring every single piece of who they are—like

puzzle pieces, each piece providing a small but vital glimpse into a survivor’s story. Each piece is interconnected and dependent on the other. These puzzle pieces are made up of a lifetime of experiences that include the survivor’s race, religion, cultural values, norms, and expectations, among others. As social workers, it is never our job to put the puzzle together, but only to hold and support the survivor as they explore each unique piece. The process is complex, messy, and uncomfortable; however, we must never ignore any one piece in an effort to avoid this discomfort. By helping the survivor examine all the pieces of their puzzle, we begin to see the person before us slowly assemble their puzzle that tells a unique story of oppression, resilience, and survival. It is a story that allows us to truly support the individual in front of us as they embark on their healing journey.

About the Author:

Ana Diaz Lopez is a licensed social worker and the Director of Programs at Safe+Sound Somerset. She holds a Masters degree in psychology, a Masters degree in social work, and is currently pursuing a DSW from the Rutgers School of Social Work.

20 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

Domestic Violence

Race’s Role in Steering Human Services Legislation

by Joann Downey, MSW, JD Government

by Joann Downey, MSW, JD Government

The pandemic has crystallized the racial disparities in how we deliver health and social services in underrepresented communities.

The equity gap has become a consideration in every piece of legislation the State Assembly Human Services Committee, which I chair, considers. It’s the reason I strongly supported A209, legislation to establish the Disparity in Treatment of Persons with Disabilities in Underrepresented Communities Commission that the Assembly unanimously passed earlier this summer.

My colleagues and I in the 11 th Legislative District learned a great deal during numerous virtual forums with members of communities of color over the past year and a half. We needed to hear from underrepresented individuals as well as those who serve them.

As we explored ways of achieving racial justice through legislation, we met with faith leaders whose churches and organizations are a critical component of providing social and health services. For many in their communities the church and other nonprofit organizations are the lifeline for people in need. We met with Black and brown doctors from area hospitals who helped us examine the distrust of the medical community that many people of color harbor. Our panels included officials in law enforcement and education and many of our

nonprofit partners. The Commission would consist of 10 public members, eight of whom would be leaders of community-based or civil rights organizations with experience in community and urban affairs in traditionally underserved populations. Ten nonvoting members of the commission would bring the expertise in State government onboard, including representatives of the Departments of Community Affairs, Labor and Workforce Development, Human Services, Health, Corrections, Law and Public Safety, Education, Children and Families, Banking and Insurance, and a representative of the Juvenile Justice Commission. A209 is now before the Senate Budget Appropriations Committee and my hope is that it will progress quickly when the legislature reconvenes after the election in November.

While the race gap in health care and social services has been apparent for many years, another development in the pandemic has widened it. That’s the shortage of social workers that grew as our population aged and more baby boomers moved into nursing homes, and more social workers reached retirement age. The pandemic brought increases in domestic abuse, homelessness, opioid addiction, youth depression and student isolation as well as unemployment.

That’s why I have continued to push to revive the Social Services Student Loan Redemption Program

NJFOCUS • September 2021 | 21

“…we must continue to work at building trust with communities that have been neglected for generations.”

to forgive up to $20,000 in state or federal student loans over four years for New Jersey residents who work full-time as direct care professionals. This shortage in social service professionals exacerbates the race equity gap, disproportionately impacting underserved communities.

As a state legislator, attorney and someone with a Master’s Degree in Social Work, and a mother of two young daughters, I have been an advocate for underrepresented communities for many years. Prenatal and perinatal care are areas where the race gap is most apparent. The state’s high mortality rates of women of color during childbirth is unacceptable.

I continue to lobby for the Department of Health to develop standardized perinatal health curriculum for community health workers that addresses common problems affecting maternal and infant health and childbirth in underrepresented communities. Our training must provide basic educational information and materials on factors and behaviors that affect maternal and infant health and childbirth. My bill, A1022, calls on the state Health Commissioner to create a curriculum that addresses alcohol and substance use, premature births and low birthweight

babies, infant mortality, shaken baby syndrome, perinatal mood disorders and other risk factors most commonly associated with maternal and infant mortality and morbidity.

We have made strides in addressing health problems for mothers and their babies in underrepresented communities that traditionally have less access to good health care and social services. I’m very pleased that the governor signed my bill, S2432, into law two years ago allowing women up to 10 prenatal care visits in a group setting. By expanding Medicaid coverage for women of color and others in need, this law keeps the health of mothers and their children a top priority. By providing better prenatal care and putting the needs of mothers and babies first we are reducing the number of preterm births that puts a tremendous strain on families as well as our healthcare system.

As we move through the pandemic trying to provide paths to better social services and more thorough health care for all, we must continue to work at building trust with communities that have been neglected for generations. By considering race in all of the social services legislation we write, we will emerge a stronger, healthier and more equitable society.

22 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

Government

About the Author: Assemblywoman Joann Downey chairs the Assembly Human Services Committee and represents New Jersey’s 11 th Legislative District.

Challenging Raceless Latinidad & Embracing the Term Latinx in Social Work Practice

by Jesselly De La Cruz, DSW, MSW, LCSW

by Jesselly De La Cruz, DSW, MSW, LCSW

“Embracing the term Latinx can empower youth that are disproportionately and deeply affected by discrimination, racism, and oppression based on their ethnic and sexual identities.”

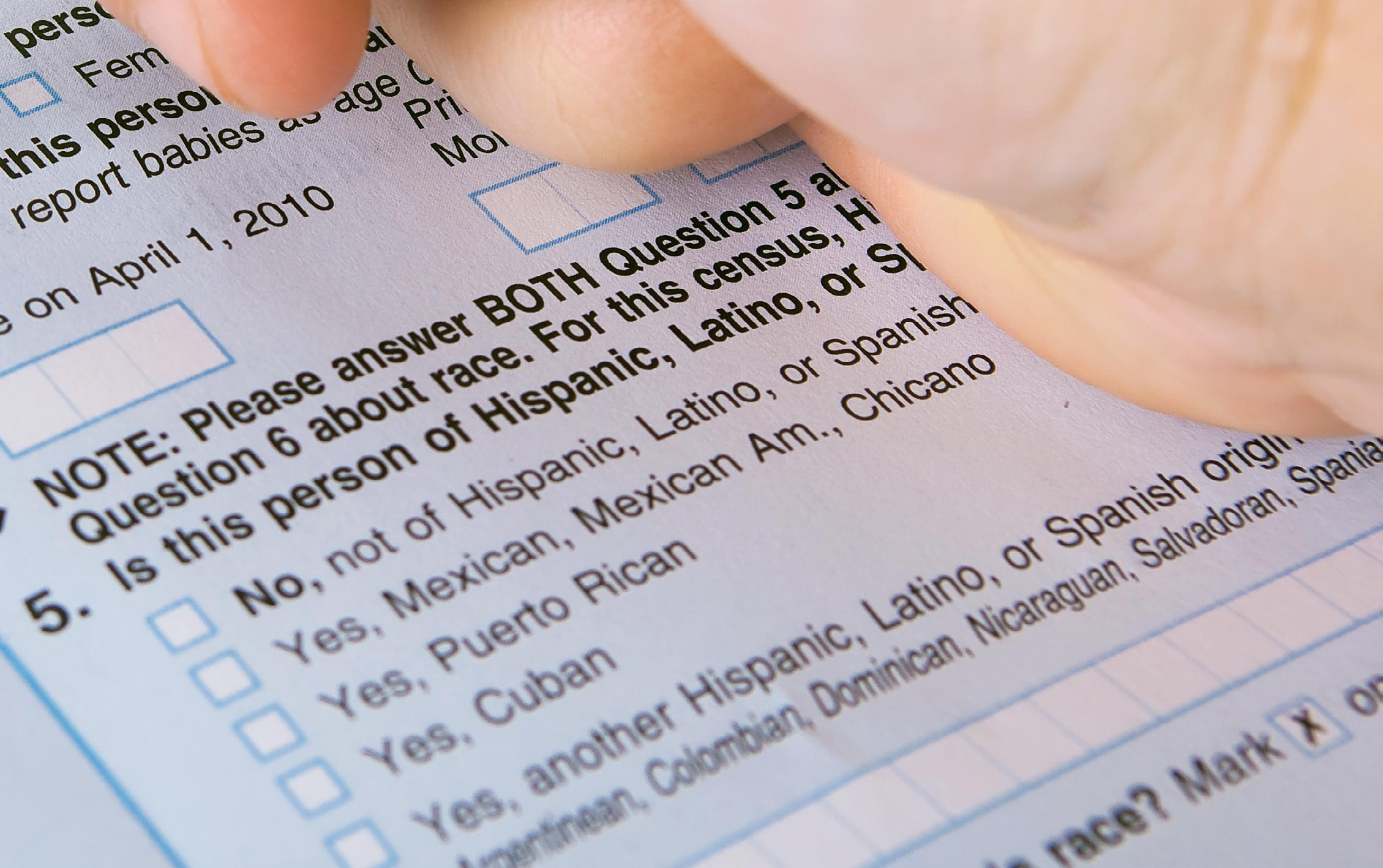

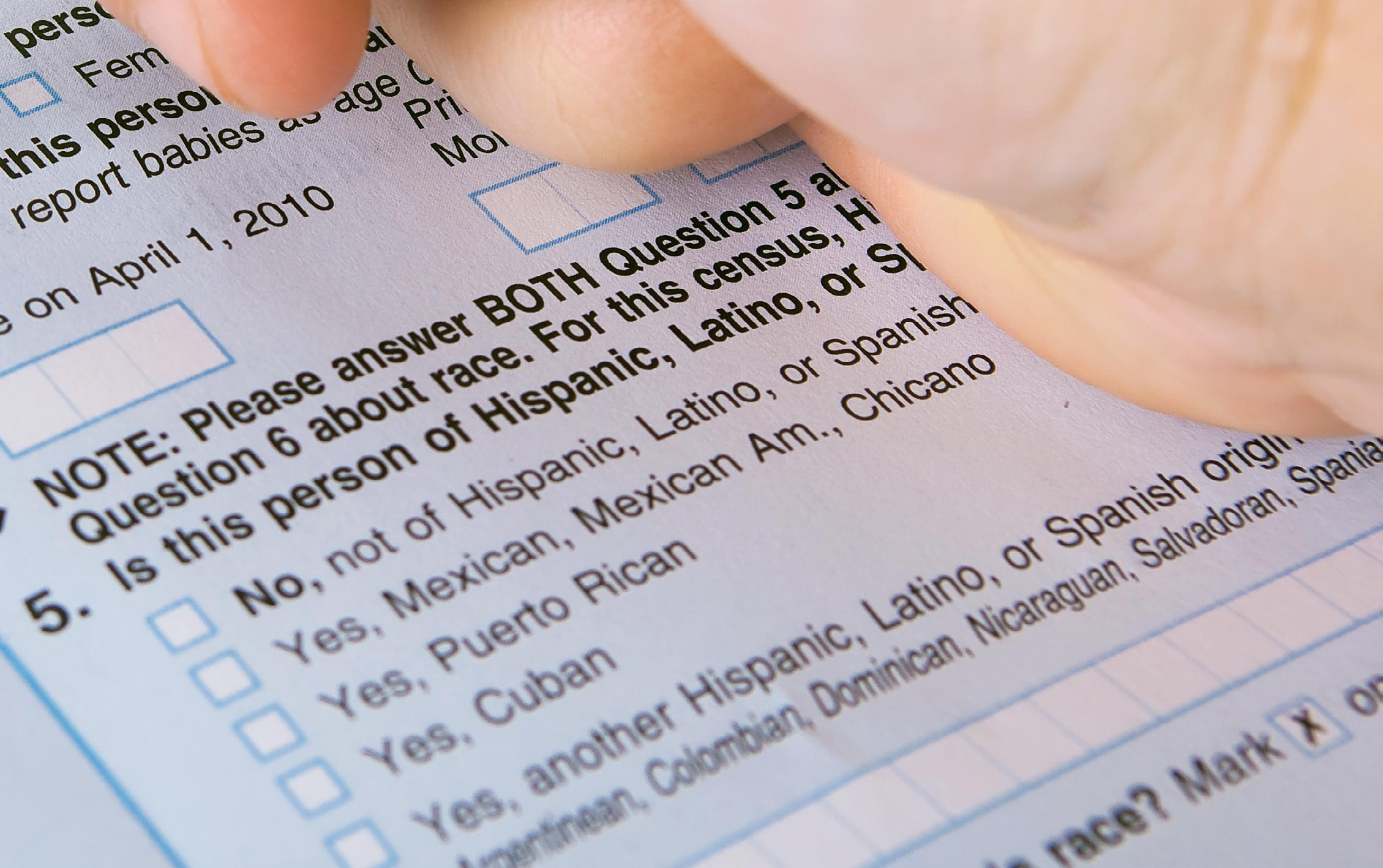

The racial diversity that is the cornerstone of the Latina/o/x experience is often made invisible. And dialogue associated with the racial origins of the identity terms Hispanic and/ or Latina/o/x is inevitably controversial in today’s polarized society. How much is being Latino/a/x still embedded in Indigenous and Afro roots? How much is adopted from European Conquest? How do we grapple with the real-life juxtaposition associated with what we call being Latina/o/x and/or Hispanic? The American government has also struggled to categorize those of Mexican, Caribbean, or Central & South American descent. The U.S. Census has flipped back and forth between labeling Latinos as their own race or inappropriately labeling us as White, with limited exceptions as to the historical evidence of Latinos having White privilege.

1930 began the first attempts by the U.S. Census to delineate the racial category of those of mixedrace, including an attempt to acknowledge the racial identity of Mexicans in the U.S. Later, in 1980, the U.S. Census introduced the ethnic, yet a-racial, political category of Hispanic as an identifier for Spanish-speaking communities residing in the states. And, while this was a technical landmark in recognizing the growing political power of this subgroup of Americans, decades later we continue to grapple with the terms Hispanic, Latino/a, and, most recently, Latinx or Latine.

Latinx is a term that was first used among student activists and in academia in 2004 as an effort to challenge the gender binary paradigm of the Spanish language. It is a term that some, mostly youth, use to have their intersectional identities— being Latino and being LGBT— acknowledged. While the term is gaining mainstream traction, few relate personally to it as evidenced by community polls and surveys. Personally, I also experienced resistance to embracing the term initially. However, I believe that broader societal resistance to the term is mostly fueled by continued widespread homophobia and transphobia and has little to do with homage to the Spanish language imposed by colonization. Latin American countries are wellknown for their historical acts of resistance. My personal and professional position is that we should embrace the term Latinx as a way of resisting reductionist narratives of what it means to be someone of Latin American or Caribbean descent in the United States.

According to the Trevor Project, Latinx youth who identify as LGBT are four times more likely to report suicide attempts than their straight, cis-gendered Latino/a peers. Embracing the term Latinx can empower youth that are disproportionately and deeply affected by discrimination, racism, and oppression based on their ethnic and sexual identities. However, the truth is that all these terms are poorly defined

NJFOCUS • September 2021 | 23

Race & Identity

as either racial categories, cultural descriptors, or reflections of gender and sexual identity representation for those of Mexican, Caribbean, or Central & South American descent living and contributing to the cultural fabric and economy of American society. The efforts to reduce Latina/o/x identity to a singular experience by choosing a universal term such as Latinx to describe our diversity is in of itself an act of oppression.

Recently in the 2020 Census, Latina/o/x and Hispanic youth have reaffirmed their diverse racial history and self-identified as multi-racial, identifying on the census with two or more races. As a feminist, I tend to lean into my privilege as a cis-gendered, light-skinned Latina and the use of Latina/o/x for myself, which happens to be alphabetical (preference to my personal gender identity, but inclusive of my queer identity) in its sequence. Most often in professional practice, I use all the terms—Hispanic, Latino/a, and Latinx— interchangeably. But, as a practitioner scholar, I realize the journey to connecting with the diversity

of experiences is not so much the terms, but the genuine, empathic understanding of the complex phenomenology of what it means to be Latina/o/x and/or Hispanic in the U.S., wherever we may be across this great North American Continent.

As social workers, we are often aware of our position of power in practice but struggle as to how to authentically balance that in therapeutic relationships. White clinicians often shy away from conversations about race, power, and privilege due to its discomfort. But, when it comes to issues of race, ethnicity, and sexual identity issues, I believe social workers have an ethical responsibility to ask the questions directly as part of initial and ongoing assessment with clients. Racial, cultural, and sexual identities are not static and, just like the politics of terms continues to change, how one identifies can also evolve over time. Social work practice benefits from the therapeutic flexibility to embrace these changing dynamics of race, gender, & sexuality issues when working with Latina/o/x and/or Hispanic clients.

About the Author:

Dr. Jesselly De La Cruz , BA in Political Science (Rider University), MSW (Rutgers University), and DSW (Rutgers University), is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker in NJ. She completed a Post-Graduate Certificate in Family Therapy at The Multicultural Family Institute, Inc. in Highland Park, NJ. Having originated from an underprivileged background and being a child of an immigrant family herself, Dr. De La Cruz's education and clinical social work practice has been motivated by her desire to support traditionally underserved populations. She currently serves as Executive Director for the Latino Action Network Foundation.

24 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

Race & Identity

JEANETTE TORRES

Hello everyone! My name is Jeanette Torres. I attend Seton Hall University as a 2nd year MSW student with a graduation date of May 2022. Being accepted into an MSW program has allowed me to advance my knowledge and support individuals in their time of need. I have had the opportunity to work with several different populations; however, my heart expanded as a caseworker in a preschool setting—providing case management, supporting family events throughout the school year, and observing the children's growth. Connecting with all parties involved (parents, teachers, social workers) to create a path of success for all the children provided me with pure joy. I’m excited to join NASW-NJ as an MSW intern to strengthen my skills in advocacy and network with other social workers who may be able to help me advance my career. An interesting fact about me: I enjoy dancing, zip-lining, and hiking—being one with nature brings much-needed calmness and clarity to the soul.

Student Center

CHARLES GIRALDO

My name is Charles Giraldo, and I am finishing my BSW at Rutgers University (graduating, May 2022). I am a military veteran, and I am passionate about helping other veterans learn how to navigate the processes at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to receive the services afforded to them as a veteran. I am aware of the challenges faced by veterans, and I am hoping to help them by implementing plans that will get them the help they need.

I chose to pursue studies in social work during my term as the student president for the Student Veterans of America (SVA) local school chapter. I saw first-hand how student veterans did not know about the benefits they can receive through the VA, which they needed so much. As more student veterans approached me, I realized that becoming a social worker would help me be able to help others better.

After completing my BSW, I intend to pursue an MSW degree, which will afford me greater knowledge and help me better understand the needs of the public and how to implement change effectively. I would eventually like to work on the macro level by advocating for veterans at the state and federal levels to help create necessary policy changes.

Beyond social work practice, I enjoy traveling and scuba diving and spending time with my wife and my dog, Roscoe.

I am looking forward to diving into my internship with NASW-NJ and working alongside experienced and effective social workers to enhance my hands-on learning experience.

MATTHEW SATO

Hi! My name is Matthew Sato (he/him) and I am a Master of Social Work student at Rutgers University New Brunswick, anticipating graduation in 2023. I chose to pursue social work because I believe that care and compassion for others can be a delicate craft, and that social workers are the masters of this craft.

As a Filipino-American, I believe that Asian-American visibility is a growing necessity in social work, as we are specialists of our shared experiences, suffering and systemic shortcomings. As a result, I am interested in Macro social work, specifically the areas of Management and Policy. Additionally, with my B.S in Business Studies, I also have a vested interest in the developing realm of corporate social work and responsibility.

Being a non-traditional Master of Social Work student, I am continuously striving to challenge myself and learn more about the expansive field of social work. With the New Jersey Chapter of NASW being one of three largest chapters in the United States, my hope as an intern is to interact with diverse populations and communities and learn how to retrofit my business education to meet the varied needs of those who are suffering. Furthermore, I am excited to explore what part the NASW plays in the development of non-traditional pathways in the field of social work!

F un F act : I love attending and letting loose at raves! I really admire the community's pillars of peace, love, unity, and respect (PLUR)!

Student Center

PARTNER SPOTLIGHT

NEWPORT HEALTHCARE: EMPOWERING LIVES. RESTORING FAMILIES.

Newport Healthcare, a leading provider of mental health treatment for teens, young adults, and families, partners with NASW-NJ to provide educational workshops and resources for its membership. This valued partnership honors the crucial role of social workers in serving individuals and families, as well as acting as professional referents when clients require a higher level of care.

In total, Newport will be hosting five programs in conjunction with NASW-NJ over the next year. The first offering, a FREE three clinical CEU webinar entitled “The Multiple Self-States Drawing Technique: Creative Assessment and Treatment with Children and Adolescents” will be held on October 22. You can find more info and register for the program here.

With the mission to provide state-of-the-art integrated care to individuals and families, Newport Healthcare guides young people to achieve long-term, sustainable healing. Its clinical model of care addresses the underlying trauma at the root of depression, anxiety, and co-occurring issues, such as eating disorders and substance abuse. Newport’s outpatient and residential treatment centers, with locations nationwide, serve

individuals ages 12–27, through Newport Academy, its teen treatment program, and Newport Institute, its young adult program.

Every client at Newport has an individualized, multidisciplinary treatment plan designed by specialists who are the best in their respective fields. Informed by a comprehensive intake process, treatment teams take into account each young person’s unique needs and history. During treatment, clients participate in a variety of evidence-based clinical, experiential, and academic/ life skills modalities, gaining tools for self-understanding, self-care, and healthy relationship-building. In addition, strengths-based education is an essential aspect of Newport’s clinical model; when teens and young adults return to their home school, college, or the workplace, they bring with them not only self-knowledge and the ability to form authentic connections with self and others, but also concrete skills and a sense of purpose and meaning.

The foundation of Newport’s unparalleled programming is its team of compassionate experts and thought leaders in the field—including psychiatrists, psychologists, family therapists, eating disorder therapists, nurse practitioners,

28 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

counselors, equine therapists, art therapists, music therapists, adventure therapists, registered dietitians, nutritionists, teachers, private tutors and more. All of Newport’s clinicians are trained in AttachmentBased Family Therapy, proven to repair ruptures and rebuild trust within the family system, so that teens and young adults can heal relational trauma and feel safe turning to parents for support when they are struggling.

Along with providing ongoing clinical training for its staff, Newport also serves as a trusted source of information and training for social workers and other mental healthcare professionals around the country, providing ongoing professional development opportunities through in-depth certificate programs, interactive online workshops, CE classes, and more.

In order to provide the most effective care for its clients, Newport is dedicated to tracking its treatment outcomes. To that end, the company rigorously captures patient data upon entry to its programs, and utilizes industry-accepted assessment tools to inform the treatment provided for each individual. While other programs may gather data, Newport Healthcare holds itself to the highest standard of accountability by partnering with a third party to analyze and validate its findings. Each year, Newport’s “The Science of Healing” report shares its most recent outcomes data, which continues to show patients’ anxiety, depression, and well-being measures improving far beyond clinical significance throughout the course of treatment.

At Newport Healthcare, providing the highestquality care for clients goes hand in hand with empowering employees and ensuring that they grow in their expertise and professionalism, and also as individuals. Moreover, Newport is dedicated to fostering a safe culture of diversity and inclusion, guided by awareness, education, and the company’s core values of love, empathy, and connection. As a steward of mental healthcare, Newport continues to build an inclusive culture that encourages, supports, and celebrates the diverse and authentic voices of its employees, clients, families, and communities.

Learn more at NewportHealthcare.com

Members Only Perks

With over 6,500 members in our New Jersey family, you are part of a larger family of social workers, a network of friends and colleagues who share your commitment to the profession and strengthening our community. While the chapter has many opportunities to connect on a broader level—from educational programs to advocacy events, there are also many great ways for you to connect with your colleagues locally or on a specific area of interest. Read on to learn some ways in which you as a member can build your connections, network and grow in smaller, more intimate spaces—and virtually!

My volunteering experiences started at a young age and have spanned my whole life.

I have assumed varied leadership roles in college, healthcare, public schools, community, and religious organizations. My role as the unit leader for the NASW-NJ Bergen/Passaic Unit was the beginning of my volunteer work for NASW-NJ, an organization I have been a member of since 1997. Initially, assuming this role felt overwhelming and daunting; however, knowing that leaders within the organization trusted and supported me made the transition smoother.

As a solo practitioner in private practice, I looked to this new role as an opportunity to expand my professional network and meet new and inspiring leaders in the social work profession. The position has provided me more insight into the challenges social workers face, as well as those faced by the many people we serve. My volunteer role has allowed me to have a seat at the Board meetings and to share new ideas for the organization while learning even more.

As the unit chair for the NASW-NJ Bergen/Passaic Unit, my role allows me to get to know new members and welcome them into our social work community, while also cultivating local programming and events to build ties and relationships among social workers within our counties. I assumed this role in November 2019 as the

THE REWARDS OF BEING A VOLUNTEER LEADER

by Melissa Donahue, LCSW

sole chair in my Unit (some Units also have co-chair positions). Unsure where to begin with programming opportunities in the midst of the holiday season, I organized a holiday party in December to get to know members in my Unit and to draw inspiration from others in our profession. At each networking event, I always ask those present to share the types of knowledge and programs they are craving to generate ideas for future events that will be of interest to my Unit members. Discussion at our first meeting, led to our partnering with nursing homes in Bergen County to provide educational and CEU programming, featuring topics like Collaborative Divorce and the Equity of Pleasure. Unfortunately, due to COVID-19, we had to cease our in-person gatherings after our free yoga class for Social Work Month in March 2020.

During the pandemic, I rapidly switched gears to make our Unit a place of emotional support for members to share their struggles and concerns during the pandemic. Then in June 2020, we began to launch online programs for our members. The online platform offered the bonus of allowing social workers from across New Jersey—and the country—to participate. While our Unit members were great receivers of education, they were also excellent givers. Our Unit members impressed me with their generous donations to our clothing drive in support of the Rain Foundation, the only LGBTQ transitional

32 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

NASW-NJ UNIT UPDATE MEMBER CONNECT

housing in New Jersey. A constant stream of clothing filled my waiting room! In addition, our compassionate outreach continued as we collected toiletries and detergent to those receiving supportive services as survivors of Domestic Violence through SOFIA.

As COVID-19 cases decreased this past spring and early summer, our Unit decided to meet in person for the first time in sixteen months. In July, we gathered outside to share our personal and professional successes and struggles, seek career guidance, and enjoy the pleasure of live human interaction. It was inspiring to see all the smiling faces and the endless face-to-face conversations following sixteen months of fatigue from online sessions and meetings. While the explosion of the COVID-19 delta variant seems destined to again put an end to in-person events, our Unit will gather in person one more time in September. Through experience we now know that we can now seamlessly switch back and forth between in-person and virtual meetings. And while I will be sad to see in-person events placed back in storage for a while, I am grateful technology has allowed us to continue to meet as a Unit and extend our offerings to the broader social work community.

With in-person events back on hold, my goal now is to provide varied virtual educational and networking experiences for all our social workers. Many of us work in isolation, and we need to actively reach out to one another for professional support and guidance. My role as unit chair has allowed me to become a leader for NASW-NJ and our social work community. It has also provided the opportunity for me to become a student of our profession and the needs of social workers from different backgrounds and work areas. This volunteer opportunity has been an important step in my professional development and has connected me to my social work community in a way I had never been before.

About the Author:

Melissa Donahue, LCSW, CST is a certified sex therapist and supervisor enhancing the lives of individuals and couples. She works in private practice in Ridgewood and Morristown, New Jersey. She is a presenter, mentor and strong advocate for accurate sexual education for all. She is currently a doctoral student at Rutgers School of Social Work.

MEMBER CONNECT

MEMBER CONNECT

MEMBER CONNECT

T h e b e a u t y o f o u r p r o f e s s i o n i s t h a t i t i s d i v e r s e . F r o m a c a d e m i a t o p r i v a t e p r a c t i c e , m a c r o s o c i a l w o r k t o h e a l t h c a r e , t h e r e i s n o a r e a t h a t s o c i a l w o r k d o e s n o t t o u c h i n s o m e w a y W h i l e w e o f t e n c o m e t o g e t h e r i n l a r g e r g r o u p s s h a r i n g o u r d i f f e r e n t p e r s p e c t i v e s a n d f r o m d i f f e r e n t p l a c e s s o m e t i m e s i t s g o o d t o f i n d y o u r s m a l l e r g r o u p o f “ p e o p l e ” s o c i a l w o r k e r s w i t h s h a r e d i n t e r e s t s o r a r e a s o f p r a c t i c e T h e s e s m a l l e r p l a c e s a r e a g r e a t p l a c e t o d i s c u s s u n i q u e c h a l l e n g e s a n d n e e d s i n t h e f i e l d , a s w e l l a s b r a i n s t o r m o n p r o g r a m s a n d h e l p s h a p e s p e c i f i c l e a r n i n g e v e n t s t h a t t h e C h a p t e r h o s t s

Over the last several months our Chapter has expanded our Shared Interest Groups to meet your needs giving you more opportunities to connect and collaborate These dedicated spaces meet on various schedules (virtually for now) and are busy sharing best practices in school social work, healthcare, and more. We invite you to check out the Shared Interest Groups and join a conversation or program. You can sign up for Shared Interest Group information here

36 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

J o i n O u r S I G s : F i n d t h e g r o u p s t h a t m a t t e r t o y o u . S h a r e y o u r S h a r e y o u r I n t e r e s t s . V o i c e . MEMBER CONNECT

MEMBER CONNECT

IDA B. WELLS CONTINUOUS MEMBER SOCIETY

Meet the Ida B. Wells Society

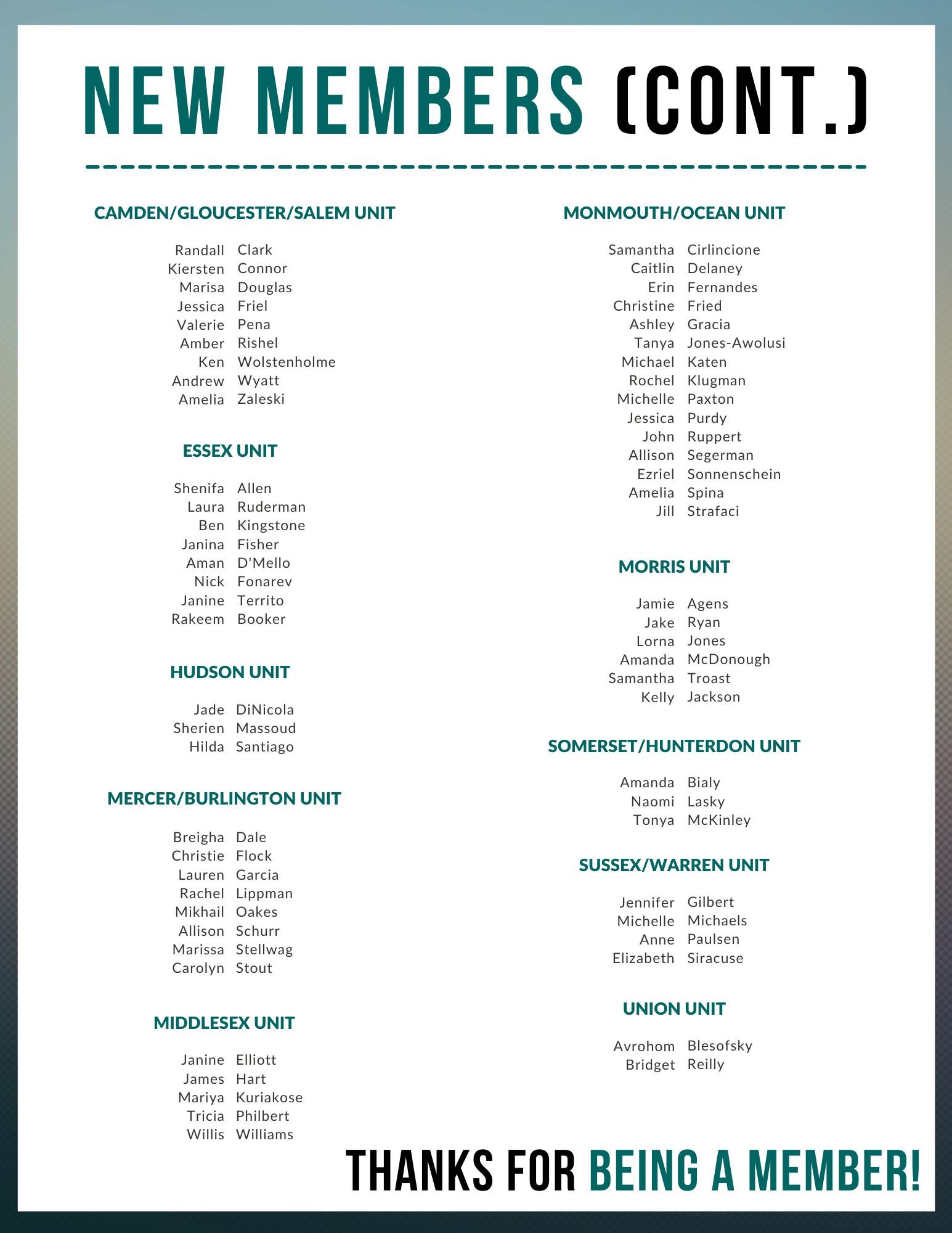

Last issue, we introduced you to the Ida B. Wells Society, NASW-NJ’s new way of recognizing social workers who have been long-time, continuous members of NASW. These members’ dedication to NASW and the field of Social Work is invaluable and our appreciation couldn’t be deeper.

We began by highlighting our Founding members last issue—those social workers who have been continuous members of NASW since the 1950’s and 60’s. This month, we’re introducing those individuals who have been continuous members of NASW since the 1970’s.

Please join us in honoring and welcoming our social work legacy members—the Ida B. Wells Society!

38 | NJFOCUS •September 2021

Ida B. Wells Continuous Membership Society

MEMBER CONNECT

Ida B. Wells Continuous Membership Society

Margaret Perryman (Joined October 1970 – 51 years)

Ronne Bassman-Agins (Joined January 1971 – 50 years)

Janet Furness (Joined October 1971 – 50 years)

ABOUT IDA B. WELLS

Ida B. Wells was a fierce activist, advocate, civil rights champion, educator, and researcher. She helped chart the course for what became the modern profession of social work, fought for women’s right to vote, sought to dismantle Jim Crow policies and practices, and was the first to expose and publish stories about the horrific lynching of Black people throughout the South.

There is no better honorific that represents the passion and commitment of our long-term members than to name their recognition society after Ida B. Wells.

MEMBER CONNECT

MEMBER NEWS

Welcome to Member News—the newest feature in NASW-NJ FOCUS. This space will be dedicated to celebrating the professional achievements of our members from around New Jersey. Have you recently received a promotion? Started a new job? Opened your own practice? Been appointed to a Board of Directors or other organizational leadership position? Had a study funded or received a grant for your work? Keynoting at a major conference? Been published in a peer reviewed journal, featured in major news media, or published a book? Declared candidacy for or won elected office? Let us know! We want to highlight your professional accomplishments to underscore the great work being done by social workers in our state. Send submissions to jfeldman.naswnj@socialworkers.org .

TAWANDA HUBBARD, DSW, MSW, LCSW...

Tawanda Hubbard, DSW, MSW, LCSW has been appointed Associate Professor of Professional Practice at the Rutgers University School of Social Work.

ERICA GOLDBLATT HYATT, DSW, LCSW, MBE…

has been dually appointed between the Rutgers School of Social Work and Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, where she will be teaching physicians and students enhanced coursework on pregnancy loss, grief, and bioethics.

STEFANIE MARKY, MSW, LCSW...

has opened a private practice, Milestones Counseling and Therapeutic Services, (www. milestonescounselingnj.com). Her practice will focus on working with individuals and groups struggling with Anxiety and Depression, with a specialization in working with children to adults with special needs.

MEMBER CONNECT

PROVIDING THE SKILLS TO GET AHEAD

Prescription Opioid Misuse and Dependence in New Jersey

September 08, 2:00 - 3:00 PM EDT

1 Prescription/Opioid CEU Register

TeleMental Health Program

September 10, 9:00 AM - 4:00 PM EDT

5 Ethics CEUs Register

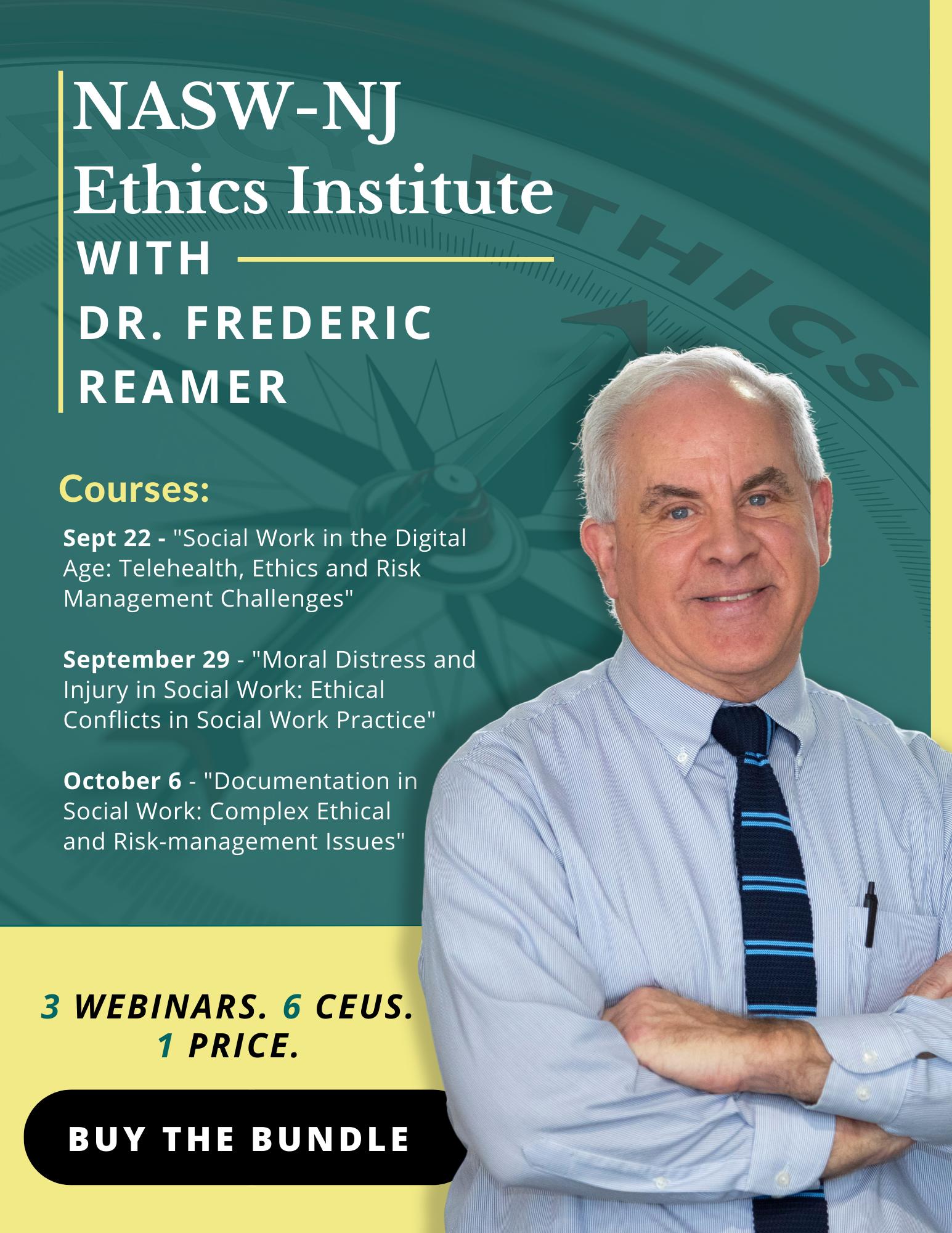

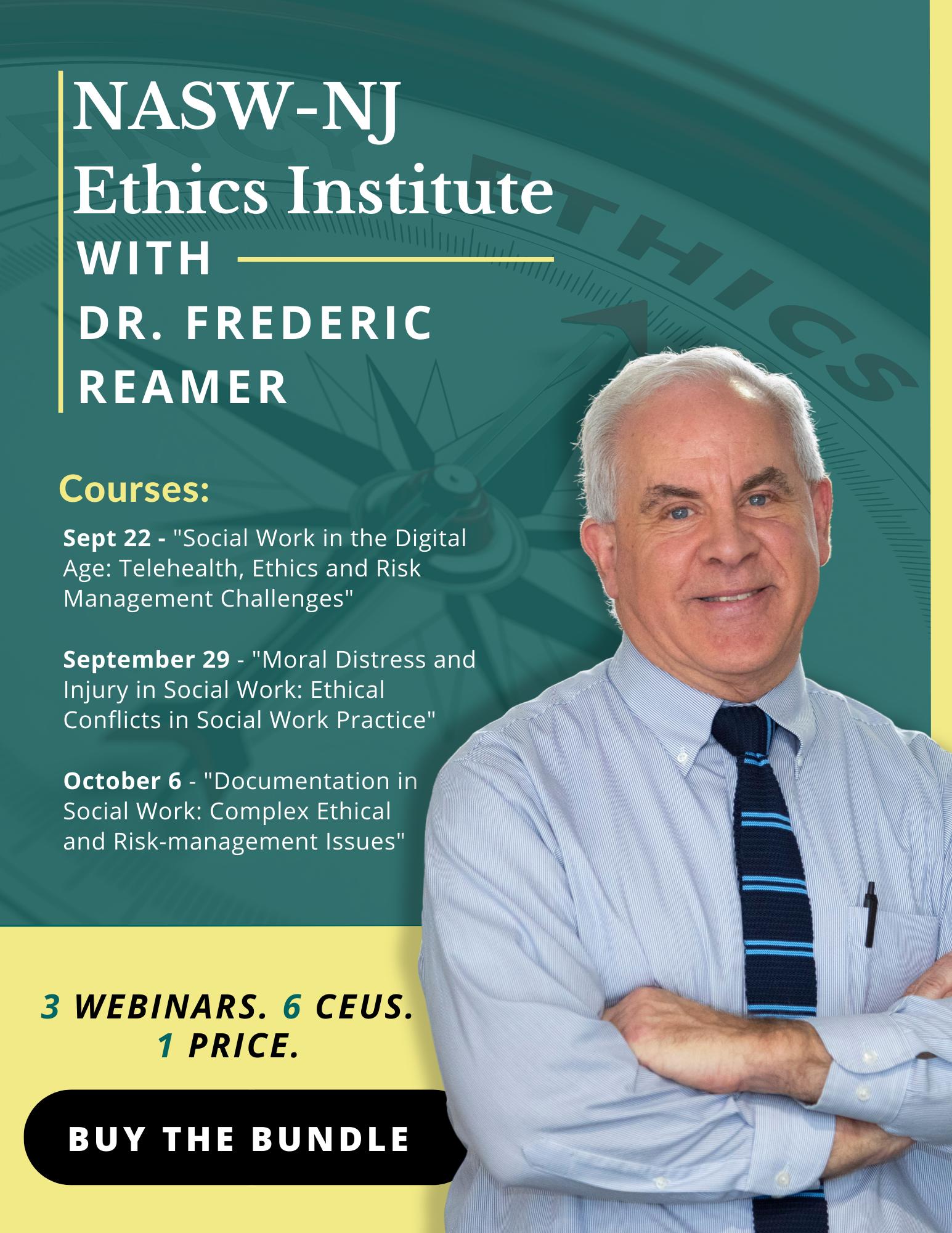

Ethics Institute with Dr. Frederic Reamer

September 22, 6:00 - 8:00 PM EDT

September 29 & October 06, 12:00 - 2:00 PM EDT

6 Ethics CEUs

Register

FREE FOR MEMBERS

Mental-Hop: Engagement, Education, and Empowerment through Mental Health and HipHop Culture

Thursday, September 23, 6:00 PM - 8:00 PM EDT

2 Clinical or Social/Cultural CEUs Register

Clinical Supervision Course (SOLD OUT)

October 08, 9:00 AM - 3:00 PM EDT

20 CEUs

Register for December 6 Course Here

Prescription Opioid Misuse and Dependence in New Jersey

October 08, 2:00 PM - 3:00 PM EDT

20 CEUs Register

Older Adults and Ethical Issues

Wednesday, October 20, 6:00 PM - 8:00 PM EDT

2 Ethics CEUs Register

FREE FOR ALL

The Multiple Self-States Drawing Technique: Creative Assessment and Treatment with Children and Adolescents

Friday, October 22, 9:00 AM - 12:00 PM EDT

3 CEUs Register

44 | NJFOCUS • September 2021

N A S W - N J S W A G

R E P Y O U R N J P R I D E

G e a r f o r s o c i a l w o r k e r s ,

d e s i g n e d b y s o c i a l w o r k e r s .

L i v e t h e v a l u e s , l o u d l y .

H O P H E R E

S

by

by

by Shonnell Flournoy

by Shonnell Flournoy

by Joann Downey, MSW, JD Government

by Joann Downey, MSW, JD Government

by Jesselly De La Cruz, DSW, MSW, LCSW

by Jesselly De La Cruz, DSW, MSW, LCSW