JOLLY

ALL THAT BAZ

As Baz Luhrmann lights up cinemas with Elvis, take a deep dive with the iconic filmmaker through his dazzling career

DECEMBER 21, 2022 OSCAR PREVIEW DEADLINE.COM/AWARDSLINE

ENGLISH: BILL NIGHY IS LIVING WITH BOWLER HATS SEX AND VIOLINS: CATE BLANCHETT & NINA HOSS GET CLASSICAL PLUS: THE DANIELS + GINA PRINCE-BYTHEWOOD + S.S. RAJAMOULI + LAURA POITRAS + EDWARD BERGER

CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

COLUMNIST

EDITORIAL

DEADLINE.COM

Breaking News Follow Deadline.com 24/7 for the latest breaking news in entertainment.

Sign up for Alerts & Newsletters

Sign up for breaking news alerts and other Deadline newsletters at: deadline.com/newsletters

VIDEO SERIES

The Actor’s Side Meet some of the biggest and hardest working actors of today, who discuss their passion for their work in film and television. deadline.com/vcategory/theactors-side/

Behind the Lens

Explore the art and craft of directors from first-timers to veterans, and take a unique look into the world of filmmakers and their films. deadline.com/vcategory/ behind-the-lens/

The Film That Lit My Fuse

Get an insight into the creative ambitions, formative influences, and inspirations that fuelled today’s greatest screen artists. deadline.com/vcategory/thefilm-that-lit-my-fuse/

PODCASTS

20 Questions on Deadline

Antonia Blyth gets personal with famous names from both film and television. deadline.com/tag/ 20-questions-podcast/

Scene 2 Seen

Valerie Complex offers a platform for up-and-comers and established voices. deadline.com/tag/ scene-2-seen-podcast/

Crew Call

Anthony D’Alessandro focuses on the contenders in the belowthe-line categories. deadline.com/tag/ crew-call-podcast/

SOCIAL MEDIA

Follow Deadline

Facebook.com/Deadline Instagram.com/Deadline Twitter.com/Deadline YouTube.com/Deadline TikTok.com/@Deadline

CHAIRMAN & CEO Jay Penske

VICE CHAIRMAN Gerry Byrne

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER George Grobar

CHIEF ACCOUNTING OFFICER Sarlina See

CHIEF DIGITAL OFFICER Craig Perreault

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS AFFAIRS & CHIEF LEGAL OFFICER Todd Greene

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS & FINANCE Paul Rainey

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS & FINANCE Tom Finn

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCT & ENGINEERING Jenny Connelly

MANAGING DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL MARKETS Debashish Ghosh

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, SUBSCRIPTIONS David Roberson

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, DEPUTY GENERAL COUNSEL Judith R. Margolin

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE Ken DelAlcazar

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Lauren Utecht

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Marissa O’Hare

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, CREATIVE Nelson Anderson

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, LICENSING & BRAND DEVELOPMENT Rachel Terrace

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL Adrian White

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Anne Doyle

VICE PRESIDENT, REVENUE OPERATIONS Brian Levine

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, CPG AND HEALTH Brian Vrabel

VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLIC AFFAIRS & STRATEGY Brooke Jaffe

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, FINANCIAL SERVICES Carla Dodds

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, TECHNOLOGY Cassy Hough

VICE PRESIDENT, SEO Constance Ejuma

VICE PRESIDENT & ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL Dan Feinberg

HEAD OF LIVE EVENT PARTNERSHIPS Doug Bandes

VICE PRESIDENT, AUDIENCE MARKETING & SPECIAL PROJECTS Ellen Deally

VICE PRESIDENT, GLOBAL TAX Frank McCallick

VICE PRESIDENT, TECHNOLOGY Gabriel Koen

VICE PRESIDENT, E-COMMERCE Jamie Miles

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, TRAVEL Jennifer Garber

VICE PRESIDENT, ACQUISITIONS & OPERATIONS Jerry Ruiz

VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION OPERATIONS Joni Antonacci

VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE Karen Reed

VICE PRESIDENT, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Kay Swift

HEAD OF TALENT Marquetta Moore

HEAD OF AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY Matthew Cline

VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC PLANNING & ACQUISITIONS Mike Ye

VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCT DELIVERY Nici Catton

VICE PRESIDENT, CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE & MARKETING OPERATIONS Noemi Lazo

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL Sonal Jain

VICE PRESIDENT, MARKETING & PORTFOLIO SALES Stephanie Parker

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL

Victor Hendrickson

DEADLINE

HOLLYWOOD IS OWNED AND PUBLISHED BY PENSKE MEDIA CORPORATION

Nellie Andreeva (Television) Mike Fleming Jr. (Film)

COLUMNIST & CHIEF FILM CRITIC Pete Hammond

AWARDS

& INTERNATIONAL EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Baz Bamigboye

EDITOR

EXECUTIVE MANAGING

Patrick Hipes

EDITOR

EDITOR, LEGAL & TV CRITIC Dominic Patten

MANAGING EDITOR Denise Petski

EDITOR Erik Pedersen

MANAGING EDITOR Tom Tapp TELEVISION EDITOR Peter White INTERNATIONAL EDITOR Andreas Wiseman BUSINESS EDITOR Dade Hayes EDITOR-AT-LARGE Peter Bart FILM CRITIC & COLUMNIST Todd McCarthy EXECUTIVE EDITOR Michael Cieply

FILM WRITER Justin Kroll CO-BUSINESS EDITOR Jill Goldsmith LABOR EDITOR David Robb

EDITOR

Goodfellow FILM REPORTER Matt Grobar INTERNATIONAL FILM REPORTER Zac Ntim TELEVISION REPORTER Katie Campione NIGHTS AND WEEKENDS EDITOR Armando Tinoco PHOTO EDITOR Robert Lang PRESIDENT Stacey Farish EXECUTIVE AWARDS EDITOR Joe Utichi VICE PRESIDENT, CREATIVE Craig Edwards SENIOR AWARDS EDITOR Antonia Blyth TELEVISION EDITOR Lynette Rice FILM EDITOR Damon Wise DOCUMENTARY EDITOR Matthew Carey CRAFTS EDITOR Ryan Fleming PRODUCTION EDITOR David Morgan EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Destiny Jackson DIRECTOR, SOCIAL MEDIA Scott Shilstone DIRECTOR, EVENTS Sophie Hertz DIRECTOR, BRAND MARKETING Laureen O’Brien EVENTS MANAGER Allison DaQuila VIDEO MANAGER David Janove VIDEO PRODUCERS Benjamin Bloom Jade Collins Shane Whitaker DESIGNERS Catalina Castro Grant Dehner SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR Natalie Sitek EVENTS COORDINATOR Dena Nguyen DESIGN/PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Paige Petersen CHIEF PHOTOGRAPHER Michael Buckner SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Kasey Champion SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, GLOBAL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT & STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS Céline Rotterman VICE PRESIDENT, ENTERTAINMENT Caren Gibbens VICE PRESIDENT, INTERNATIONAL SALES Patricia Arescy VICE PRESIDENT, SALES & EVENTS Tracy Kain SENIOR DIRECTOR, ENTERTAINMENT Brianna Corrado DIRECTOR, ENTERTAINMENT London Sanders DIRECTOR, DIGITAL SALES PLANNING Letitia Buchan SENIOR DIGITAL ACCOUNT MANAGER Cherise Williams SALES PLANNERS Luke Licata Kristen Stephens SALES ASSISTANT Daryl Jeffery PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Natalie Longman DISTRIBUTION DIRECTOR Michael Petre PRODUCTION MANAGER Andrea Wynnyk

DIRECTOR & BOX OFFICE

Anthony D’Alessandro SENIOR

SENIOR

MANAGING

DEPUTY

SENIOR

POLITICAL

Ted Johnson INTERNATIONAL TELEVISION EDITOR Max Goldbart INTERNATIONAL FEATURES EDITOR Diana Lodderhose INTERNATIONAL BOX OFFICE EDITOR & SENIOR CONTRIBUTOR Nancy Tartaglione INTERNATIONAL TELEVISION CO-EDITOR Jesse Whittock ASSOCIATE EDITOR & FILM WRITER Valerie Complex ASSOCIATE EDITORS Greg Evans Bruce Haring CONTRIBUTING EDITOR, ASIA Liz Shackleton SENIOR TELEVISION REPORTER Rosy Cordero SENIOR INTERNATIONAL FILM CORRESPONDENT Melanie

First Take 4 BILL NIGHY: The lanky louche lounge lizard that literally loves Living 8 QUICK SHOTS: Cutting to the chase in Top Gun: Maverick and giving White Noise a coat of many colors. 10 ANIMATION: By hand or computer, it’s the luck of the draw. 14 ON MY SCREEN: Black Panther’s Danai Gurira shares the power of ‘no’ and the happiness of Ghanaian palm wine. Cover Story 16 KING OF BAROQUE: Baz Luhrmann talks about the wonder of Elvis Presley and takes a look back at his own flamboyant filmography. Dialogue 26 THE DANIELS 28 GINA PRINCE-BYTHEWOOD 32 S.S. RAJAMOULI 36 LAURA POITRAS 40 EDWARD BERGER Craft Services 44 INFINITY WARDROBE: Three designers on their greatest capes in The Batman, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever and Thor: Love and Thunder. The Small Screen 48 NEW TV: The Patient’s Domhnall Gleeson, plus Niecy Nash from Dahmer - Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. The Partnership 50 CATE BLANCHETT & NINA HOSS: The Tár stars discuss the unfinished sympathies of Todd Field’s classical music drama. Flash Mob 56 CONTENDERS FILM: Deadline’s conversations at LA3C. ON THE COVER: Baz Luhrmann photographed for Deadline by Josh Telles.

TELLES/DEADLINE CALL SHEET

JOSH

T I A

R K

S E T

THE CAT IN THE BOWLER HAT

By Damon Wise

By Damon Wise

F

SONY PICTURES CLASSICS/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

QUICK SHOTS 8 | ANIMATED FEATURES 10 | ON MY SCREEN: DANAI GURIRA 14

The laconic British star of Living on taking the scenic route to Hollywood

After some 50 years in the business, Bill Nighy is used to people getting his surname wrong. It actually rhymes with ‘sigh’: the ‘y’ is silent. “My dad was very particular about it,” he says, “and for a while, I used to correct people on his behalf, because he couldn’t bear it when people said ‘Nigh-y’. It really got to him. But I’m very, very accustomed to it. The first time I was ever in a show that was reviewed in a paper, I was Bill Nigby. I’ve been Bill Nighty—that’s a regular one— and if there’s one more than any other, it’s Nighly. It’s funny, when people get things wrong, they don’t get them wrong by simplifying them, they get them wrong by making them more complicated. So, they lengthen my name. It’s always slightly longer than it should be.”

Nighy recently turned 73, and his birthday gift is awards buzz for his role as Mr. Williams in Oliver Hermanus’s Living, a 1953-set remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru, in which he plays a repressed British bureaucrat diagnosed with a terminal illness. The part was written for him by screenwriter Kazuo Ishiguro, and the actor was thrilled.

“Well, it’s a conspicuously marvelous role,” he says. “You’ve got a man who has dedicated his life to an institution that’s designed to enable procrastination, and then he’s put in an extreme situation that galvanizes him into trying to actually make something happen rather than prevent something from happening. A major part of the appeal

was that I’m interested in the degree of restraint that people required of themselves in the 1950s in England. It’s probably very bad for you, and I’m sure the psychiatric establishment would agree. But there’s something funny about it, and it’s also kind of heroic the way people didn’t trouble each other with their deeper feelings.”

It helped, he says, that Sandy Powell’s wardrobe department gave him a defined look: a period threepiece pinstripe suit. “I like it when I only have one costume,” he says. “I get institutionalized in it, and I like the fact that you don’t have to make any more decisions.”

The headwear, however, was a different matter. “It’s the weirdest item, a bowler hat. And if you’ve ever worn one, you’d know it. They’re very, very heavy—it’s like wearing a crash helmet. Quite what they’re protecting themselves from, I don’t know, but somehow it caught on. I have no idea why, but I don’t think it impeded me in the role in any way because it added to his general unease, which was quite useful.”

Nighy began acting at school, but despite encouragement from his drama teacher, he didn’t ever really see it as a career. “It wasn’t like now,” he says, “where people know about being an actor. There wasn’t so much

coverage in those days.” The way he puts it, his interest was “just one long exercise in displacement activity”: all his heroes were mostly writers or musicians. “Like every second child who’s read a book, I thought, ‘Oh, I could do that.’ And it turned out I didn’t have the courage or the resolve to be a writer.”

Instead, he drifted into drama school. “And even then, I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just do a couple years here, then I’ll work out what I really want to do.’ But then I got a job in a theater, painting sets. In those days, you could do jobs like that. It was very good. You could watch other actors, and that’s when I started to learn. I didn’t learn anything at drama school, apart from how to deal with being very, very nervous because it was always very alarming to me, standing in front of a load of people and acting.”

After a successful stint in regional theater, Nighy came to London in the late ’70s and made his big-screen debut as a delivery boy in 1979’s The Bitch, starring Joan Collins. All that comes to mind these days is the line, “Flowers for Mrs. Salmon!” and the fee.

“They gave me 150 quid,” he says. “It’s funny what you remember.”

After that, he played five journalists on the trot, and he credits

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 5

Left, Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru; below, Aimee Lou Wood and Bill Nighy in Living.

his agent, Pippa Markham, with keeping him afloat in the industry. “She was clever enough to send me out for what would be called character roles,” he says. “I wasn’t comfortable with what I was supposedly eligible for, which was to be a young leading man, and that was a pretty competitive field. I had no sense of myself as romantic, or desirable, or anything of that kind. I didn’t realize that you didn’t have to be it; you just had to act it. And I was terrible at auditioning. I used to get too nervous, so if I had an accent to do or just something to occupy me, I had a better chance of getting the job.”

The actor came to a crossroad his career with 1998’s Still Crazy, in which he appears as aging rock singer Ray Simms. The audition was held at 9 a.m. in a disused tax office somewhere near Pinner, where Nighy was confronted by his biggest fear: a karaoke machine. “When karaoke was inaugurated, I made a vow that, whatever the weather, I would never ever be in front of a karaoke machine. It’s my nightmare.”

On top of that, he had to wear flared velvet loon pants, a top that left his midriff exposed, and four-inch platform shoes. “I was 46,” he says, “and they put me in hair extensions. There was just me, the director and the cameraman. They gave me a microphone stand and… guess what? I had to sing karaoke to ‘Smoke on the Water’ by Deep Purple. I had two choices: leave the building and say, ‘I can’t do this,’ or simulate sex with the mic stand. Which is what I did. I saw the cameraman’s shoulders wobble because he was laughing so hard, and that made all the difference.”

Ray Simms revealed a dryly funny, self-satirizing side of Nighy that led directly to his most famous role, as pop star Billy Mack in Richard Curtis’s Love Actually in 2003, and it’s about this time that words like “louche” start popping up in his press cuttings. A lot. “All the words that seem to describe me begin with L,”

he says. “There’s louche, lanky—obviously—languid, laidback… ” He laughs. “Try taking a wander through my head and see if I’m laidback!” Perhaps the best description, though, came from comedian Billy Connolly. “He said I had rock and roll legs, which I was very flattered by.”

Love Actually opened the door to Hollywood, leading to a call from Gore Verbinski asking him if would play the amphibious villain Davy Jones in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. Nighy was reluctant, but Verbinski was insistent. “Come on,” said the director, “how many times do you get to be in a pirate movie?”

The biggest problem was that Nighy didn’t know a thing about motion capture. “They showed me pictures of the octopus man, and it was the scariest thing on the ocean waves,” he recalls. “Then they handed me a pair of computer pajamas and put 250 dots all over my face. Johnny Depp and Orlando Bloom were there, looking like gods, and I looked like somebody who didn’t get into Devo. It was pretty sad. But I’m quite proud of myself. I spent those first couple of days wandering about with white bobbles all over my pajamas and all over my face and a skull cap with a bobble on the top, and I didn’t run to the airport.”

For most of his career, Nighy has done theater in tandem with his film work, although he hasn’t been on the stage since 2015. “I’ve done a lot of it,” he says, “but I don’t know that I’ll do any more. But then, I say that every time. Every first night I stand in the wings saying the same thing: ‘This must never, ever be allowed to happen again.’ But once you get going, and if the wind is behind you, it can be a bit marvelous. And you get a kind of instant reaction, especially if it’s funny. I only do plays with jokes in; I think it’s vulgar to invite people to sit in the dark for two hours and not tell them a joke.”

Is there anything left for him to conquer? “I don’t think like that,” he says. “I’ve never thought like that. When I was younger, people used to say, ‘Are there any roles you’d burn to play?’ No, I don’t burn to play anything. I don’t burn to act. I remember when I was starting out hearing two things that I thought instantly disqualified me. One was that somebody asked Laurence Olivier, ‘What’s the major requirement for being an actor?’ and he said, ‘100 percent confidence.’ I thought, ‘Well, I have zero confidence, so that counts me out.’ And then I read that Rod Steiger once said, ‘You have to burn to act. If you don’t burn, don’t act.’ Well, I’ve never burned, Rod, so I can’t.” ★

6 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE FT CLOSE-UP SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

Nighy as Mr. Williams in Living

Cut for Time

How editor Eddie Hamilton wove together “punchy, exciting” sequences for Top Gun: Maverick

Top Gun: Maverick follows Maverick (Tom Cruise) as he returns to the Top Gun flight school to prepare a new class of pilots for a dangerous mission. For this sequel, the filmmakers gave editor Eddie Hamilton the challenge of compressing more than 800 hours of footage into a movie just over two hours. “It was quite honestly very overwhelming

to create simulated storyboards of what the final sequences would look like. “Quite often we would have these model jets on wooden sticks,” he says, “and we would literally move the jets around and film them with our phones… It was very hard to watch for ages, and it required a lot of imagination.”

Once the exteriors of the jets were shot, Hamilton needed to search through the footage to piece together the final product, which involved a lot of cutting. “The first dogfight scene, where Maverick’s shooting the pilots down and they’re doing the pushups, started out at about 15 minutes long,” says Hamilton. “In the finished movie,

Tom Cruise in Top Gun: Maverick at times,” he says. “There was one day when they had 27 cameras running because there were four jets up in the air with various cameras on them.” Since the interior shots were filmed months prior to the exteriors, Hamilton needed

it’s like four minutes and 50 seconds, so you can imagine it just got compressed and compressed, so only the very best shots were left at the end. We always wanted it to be this kind of punchy, exciting, dynamic, fun, entertaining sequence.”

Ryan Fleming

Visible Spectrum

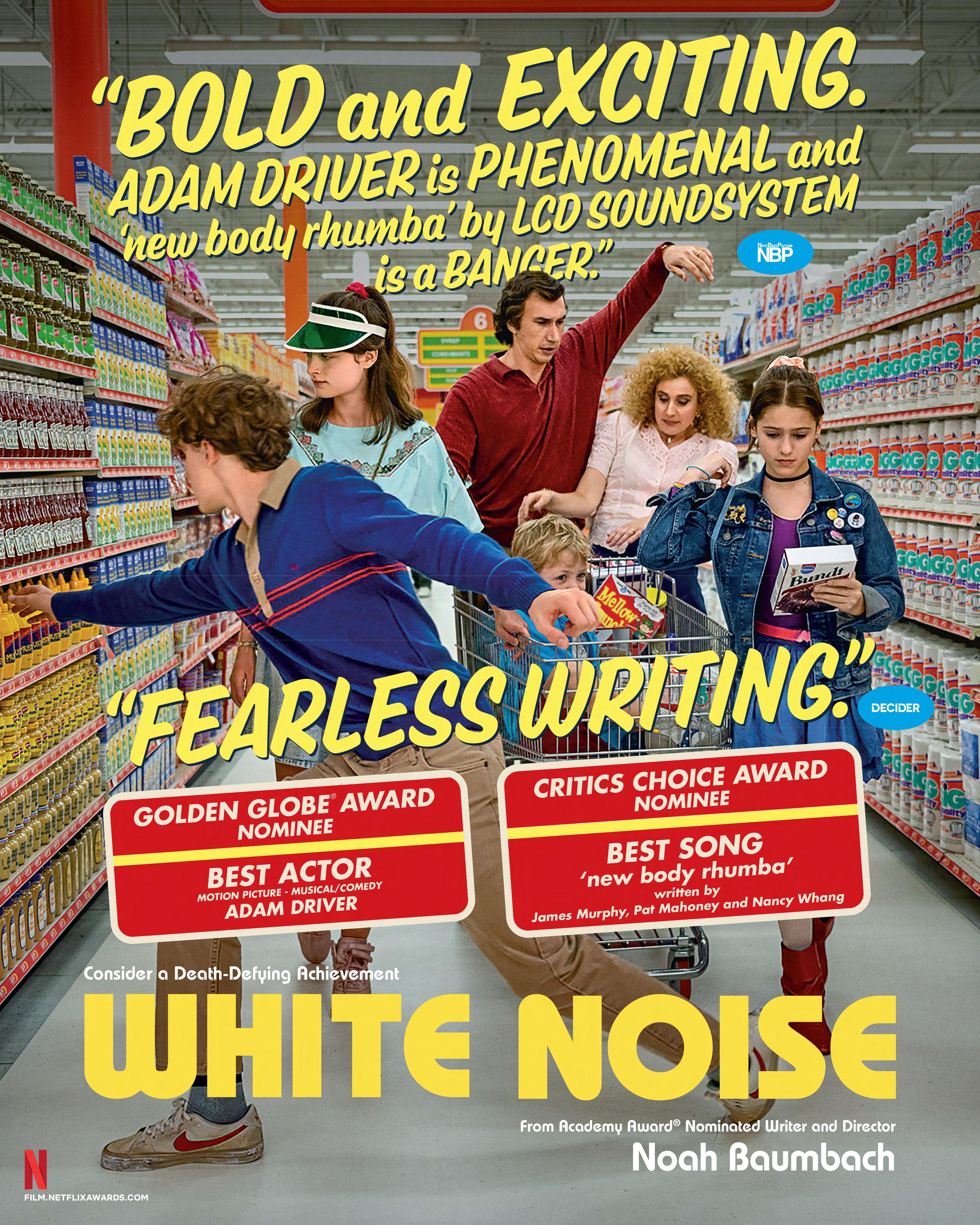

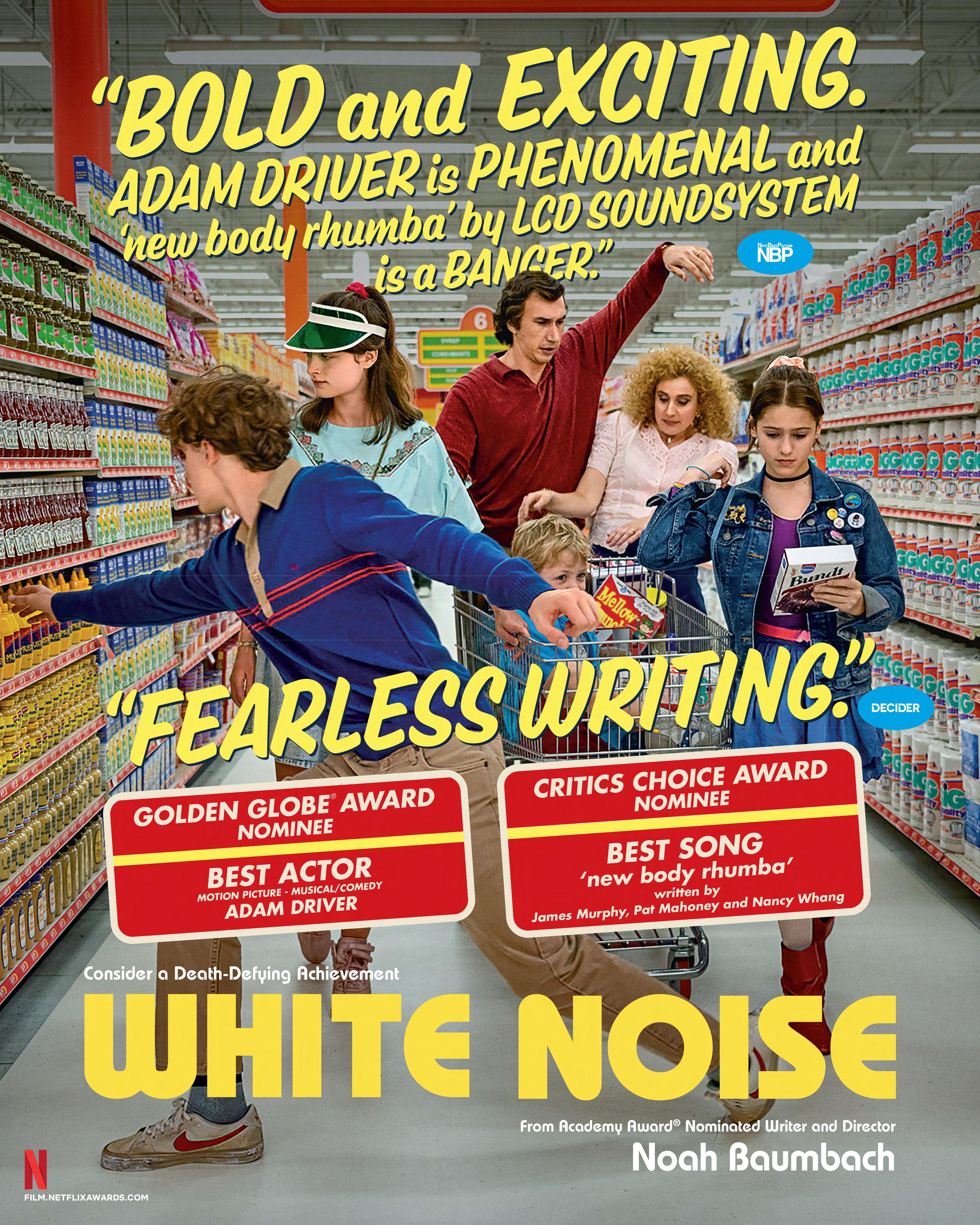

Production designer Jess Gonchor on using a “Rubik’s Cube” of color for White Noise

The story of White Noise focuses on a family’s everyday life after a toxic chemical spill forces them to face their mortality. Production

designer Jess Gonchor added a vibrancy to the setting to juxtapose the fear of death prevalent in the film. One setting used to achieve that was the supermarket, which also highlighted American consumerism in the ’80s. “It was filled with things that had shelf life and longevity, and bright colors and graphics,” he says. “That was the ‘life’ that counteracted with every-

body’s fear of death in the movie.”

While Gonchor usually sticks to a few colors in his designs, he says he drew inspiration from the “simplicity and the color” of the Rubik’s Cube for this project. “All the primary colors are there,” he says, “and when you mix it up, it’s graphic and colorful in a way that was such a huge thing in the ’80s.”

Ryan Fleming

Charted Territory

At press time, here is how Gold Derby’s experts ranked the Oscar chances in the Director and Animated Feature races. Get up-to-date rankings and make your own predictions at GoldDeby.com.

8 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 1

2

3

4

5

1

2 The

3

4

5

Pinocchio ODDS 82/25

Turning Red ODDS 4/1

Marcel the Shell with Shoes On ODDS 11/2

Puss in Boots: The Last Wish ODDS 17/2

Strange World ODDS 11/1

Stephen Spielberg The Fabelmans ODDS 82/25

Daniels Everything Everywhere All at Once ODDS 5/1

James Cameron Avatar: The Way of Water ODDS 7/1

Martin McDonagh The Banshees of Inisherin ODDS 15/2

Sarah Polley Women Talking ODDS 17/2 Director Animated Feature

FT QUICK SHOTS WILSON WEBB/NETFLIX/PARAMOUNT/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

From left, Adam Driver, Greta Gerwig and Don Cheadle in White Noise

AN ANIMATED DEBATE

By Ryan Fleming

Disney swept the animation category with three nominations last Oscar season, culminating in a win for Encanto. This year, Netflix is coming on strong with more than a few contenders, including Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio. DreamWorks Animation is back with a few contenders of its own, while Apple, A24 and GKIDS are seeking their first Oscar win for Best Animated Feature. With only five nominations available, who will go on to compete for the prize?

Walt Disney Studios has a few contenders this year, but their frontrunner is Pixar’s Turning Red. Director Domee Shi revisited her own awkward teen years to create a story of a young girl struggling to please her family as she enters adolescence. Turning Red follows Meilin Lee (Rosalie Chiang), a 13-year-old Chinese Canadian girl from Toronto who works at her family’s temple to make her mother, Ming (Sandra Oh), proud. Due to a family blessing/curse, Mei transforms into a giant red panda whenever she experiences strong emotions, which is less than ideal for a teenager. The film, which marks the first from Pixar to be solely directed by a woman, has received critical acclaim for Shi’s depictions of female friendships and the motherdaughter relationship.

After 25 years of working in Disney animation, director Chris Williams decided that Netflix was the right place to finally make the animated action-adventure he always dreamed of, with The Sea Beast . The film follows Jacob (Karl Urban), a hunter of sea monsters, and Maisie (Zaris-Angel Hator), a young stowaway, as they join the crew of the Inevitable and embark on a hunt for the elusive Red Bluster. After falling overboard during a difficult battle, Jacob and Maisie find themselves stranded on a deserted island surrounded by beasts. The pair soon discover that the beasts are not as sinister as they are rumored to be, which causes Jacob to grapple with the idea of what it truly means to be a hero. Sony Pictures Imageworks, which also animated Netflix’s last nominee The Mitchells vs. the Machines , was challenged by Williams to craft scenes of epic battles between hunters and the beasts on the sea, which is a notoriously difficult setting to animate. The Sea Beast has become Netflix’s most successful animated film to date, with more than 160 million hours viewed.

Netflix’s next competitor is My Father’s Dragon, directed by Nora Twomey and based on the 1948 children’s novel of the same name. The film follows Elmer (Jacob Tremblay), a young boy who helps his mother run a candy shop in their small town. When the store is forced to close, as the town’s population dwindles, he and his mother move to a crowded city where the ensuing hardships lead to a rift in their relationship that causes Elmer to run away. A cat he befriended, voiced by Whoopi Goldberg, tells him of a dragon being kept on Wild Island that could solve all of his problems. On the island, he meets a clumsy and curious Boris the Dragon (Gaten Matarazzo) and the two set out on an adventure to save Wild Island. As opposed to the 3D animation of The Sea Beast, My Father’s Dragon sticks to a 2D storybook style, which has led to positive reviews and popularity among younger viewers.

10 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE FT FEATURE

As the competition heats up, which animated feature will bring home the Oscar?

DISNEY STUDIO MOTION PICTURES/COURTESY

COLLECTION

NETFLIX/WALT

EVERETT

The Sea Beast

Turning Red

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio delivers a visually stunning stop-motion adaptation of the Pinocchio fable, reimagining the story in 1930s Italy during the Fascist reign of Benito Mussolini. After the loss of his son Carlo due to an aerial bomb, woodcarver Geppetto (David Bradley) carves a wooden boy from the tree at Carlo’s grave, which has recently become the home of a cricket named Sebastian (Ewan McGregor). A mysterious Wood Sprite (Cate Blanchett) brings the puppet to life, names him Pinocchio (Gregory Mann), and promises to grant Sebastian a wish if

he serves as the boy’s conscience. Co-directing with Mark Gustafson, Del Toro brings his signature artistic style to the project, injecting a shot of playful anarchy into the tale of a boy trying to live up to his father’s expectations.

DreamWorks Animation is back in the mix this year with two major contenders in The Bad Guys and Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. Based on a children’s graphic novel series, The Bad Guys follows a group of anthropomorphic criminals, Mr. Wolf (Sam Rockwell), Mr. Snake (Marc Maron), Ms. Tarantula (Awkwafina), Mr. Shark (Craig Robinson) and Mr. Piranha (Anthony Ramos). After getting caught, Mr. Wolf makes a play to escape prison time by claiming that the group wants a chance to reform themselves into good guys. Though it starts as a ruse, Mr. Wolf soon finds himself excited by the opportunity to better himself. The film grossed more than $250 million worldwide and was the second-highest-grossing animated film of 2022.

DreamWorks earned their first Best Animated Feature Oscar in 2001 with Shrek, and this year they are bringing the sixth installment in the series with Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. The story takes place after Shrek Forever After, when Puss in Boots (Antonio Banderas) is accidentally killed by a bell and discovers he is down to his ninth, and final, life. He soon learns about a wishing star that could help them get his lives back. However, during his quest he is hunted by a mysterious wolf. Puss in Boots: The Last Wish has yet to have its wide theatrical release, but early reviews for the film have been positive.

A24 has entered the race this year with Marcel the Shell With Shoes On, based on a series of short films written by director Dean Fleischer Camp and Jenny Slate. Using a documentary style, it sees filmmaker Dean (Fleischer Camp) move into an Airbnb where he finds a tiny talking shell named Marcel (Slate). Marcel lives in the home with his grandmother

Connie (Isabella Rossellini) and has created whimsical and resourceful ways of dealing with problems in his everyday life. Dean begins filming Marcel’s antics and uploads the videos to YouTube, leading to Marcel becoming a cultural phenomenon that attracts the attention of 60 Minutes’ Lesley Stahl. Although the film has animated characters interacting with the live-action world, it was deemed eligible to be nominated for Best Animated Feature and has since gained a lot of traction in the race.

After receiving its first nomination in the category for Wolfwalkers in 2021, Apple is looking to get its second nomination this year with Luck, directed by Peggy Holmes. Sam (Eva Noblezada) is the unluckiest person in the world. Her life changes for the better when she finds a lucky coin, which her bad luck soon causes her to lose.

Bob (Simon Pegg), a black cat with a Scottish accent, comes looking for the coin, only to accidentally bring Sam into the mystical Land of Luck where the two must go on a journey to find it and turn her luck around. The film’s strength lies in its voice acting and choreographed animated sequences, which were enhanced by Holmes’ background in dance.

Though Belle didn’t garner the nomination last year, GKIDS has a new chance with its animated musical Inu-Oh. Based on the novel Tales of the Heike: Inu-Oh by Hideo Furukawa, the film follows two outcasts

in 14th-century Japan: Tomona (Mirai Moriyama), a blind Biwa player, and Inu-Oh (Avu-chan), a deformed Noh dancer born with a curse. The two discover they have the ability to hear the spirits of the Heike, a clan of warriors whose stories are lost to time, and the pair begin to perform their stories in a new style resembling modern hair metal. Inu-Oh’s performance recounting the Heike stories starts to cure him of the curse and rockets them to stardom, but they soon attract the attention of the country’s leading power, who doesn’t want these stories told. The film received immediate critical acclaim as a story of artists compelled to speak truth to power through an exciting performance style.

Last year’s winner, Encanto, received a huge bump in popularity thanks to the song “We Don’t Talk About Bruno”, but this year, there haven’t been any songs going viral to keep a film in the public eye. Will Disney or DreamWorks be able to pull off another win, or will Netflix finally break through with multiple films, including Del Toro’s long-awaited iteration of Pinocchio? Will GKIDS or Apple secure their first win after receiving only nominations, or will A24 deliver a surprise upset with Marcel the Shell? Compared to last year, this season seems like anyone’s game to win.★

12 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE FT FEATURE

NETFLIX/PARAMOUNT/A24/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

Above, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio; below, Luck

Marcel the Shell With Shoes On

DANAI GURIRA

By Antonia Blyth

In the sequel Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, Danai Gurira resumes her role of Okoye—a part she has also played in the Avengers franchise. This time, Okoye is assigned by Queen Ramonda (Angela Bassett) to watch over Shuri (Letitia Wright) as she ventures into the threatening outside world, with mixed results. While there was pain in returning to Wakanda following the tragic death of Black Panther star Chadwick Boseman, Gurira also cites a strong drive to honor his memory, too.

Also a Tony-nominated playwright, Gurira first became a fan-favorite household name as Michonne in AMC’s zombiethon The Walking Dead, and she will soon executive produce and star in an upcoming spin-off series, co-starring Andrew Lincoln as Rick. Here, she reveals her desert island films, onscreen guilty pleasures, karaoke playlist and more.

My First Film Lesson

That they feed you all the time, because I’m from theater where they don’t feed you. You’ve got to bring your own food, bring your own snacks. It’s not happening. It’s like, “OK, can I just take this? Really? All this is for me? I can just eat whatever I want right now?” It’s just always there.

The Best Advice I Ever Received

The power of the word ‘no’ and how that can be a very defining word for who you are, what you stand for, and what you want to be in the world, as well as where you’re trying to go. It also allows you to not be a people pleaser, because you’ll really stand in that word and stand by it. You’re not trying to please everybody. That’s something that women often get conditioned into having to be sometimes, just to survive a patriarchal society. I think it has really helped me go on a route that makes me feel like this is who I am, and this is what I’m meant to be doing in the world, and I’m defining it.

The Part I Always Wanted To Play

I do love doing action stuff. I did tons in Walking Dead, tons in these last two movies of Black Panther

and The Avengers. It’s something that I know I have an ability in, but I also really love to do. I guess I’m a bit of an adrenaline junkie, so I’m always like, “Yeah, I want to do an action flick,” but I think I might have to write it myself. I don’t see where the scripts are that feed my specificity that way. I don’t expect someone to call me up with that perfect script, so I think I’m going to have to write it myself. That’s usually where I land up.

The Most Fun I’ve Had On Set

There was a day [on Wakanda Forever] where we were in this little Lexus, and it was me and Lupita [Nyong’o], and we had to run out of the casino and jump in the car. We had this South African house music playing and we’d hit it, throw it back on, and just be jamming. They’d be like, “Danai, Lupita, get out the car. Danai, Lupita, please come back.” We’d just be like, “Huh? Can’t hear you,” and we’d be jamming in the car forever. Then there was another day with Martin Freeman where he was driving this Land Rover. I probably shouldn’t say this, but we had a little Ghanaian palm wine in the car. We had this ’90s jam channel playing and he knew every single ’90s R&B word.

14 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE FILM FRAME/MARVEL STUDIOS/AMC STUDIOS/LARRY MARANO/GETTY IMAGES/PARAMOUNT/NETFLIX/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

The Black Panther: Wakanda Forever star recalls laughter, tears, and lessons learned

FT ON MY SCREEN

Gurira in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Danai Gurira in The Walking Dead

My Toughest Role

There is a very particular climb that starts off with the beauty of Maya Angelou’s words about how glad I am to be a Black woman. I would be jealous were I anything else. You start with that thankfulness for all the things that come up being a Black woman, but it also comes with the struggle. That definitely is something that I’ve seen experienced by others, and I’ve experienced in work and in life. There’s a clarity inside that the way things are, the barriers that exist, shouldn’t be there, so you strive to not even pay them any mind, but rather, just to destroy them with the pursuit of the work and the pursuit of the purpose. You destroy them, not just

for yourself, but for those coming after you. I think about the women who’ve come before me who’ve done that so beautifully.

The Films That Make Me Cry

I think I cry pretty easily. I cried during Wakanda Forever. I haven’t been able to sit down with the big screen yet and watch The Woman King. I’m sure I’ll cry when I see that. What else has made me cry? Probably back in the day, Dirty Dancing made me cry.

The Character That’s Most Like Me

I don’t think I’ve played a character the most like me, because I’m bizarre. I have a very nerdy side and I have a very gushy side. I have people tell me I’m funny. I don’t know if I am, but I don’t think I’ve been able to play a character that really embodies me so much that I can really say, “Well, that was just me.”

My Most Quoted Role

There were a lot of quotes from the first movie that came out of Okoye that I saw everywhere, that people quoted back to

me, that were being used at anti-gun rallies in DC. There were just so many. And then even something she says in Avengers that people really started to quote back to me a lot, too. I think it’s definitely Okoye. I mean, there are some things Michonne has said that I would definitely see hardcore fans would have on T-shirts, or they’d want me to write it when I was signing their sword replica. In Season 3, Episode 12, she says, “The mat said welcome,” because she was defending the fact that she was eating Morgan’s food, and people would quote that back to me. And, “We’re the ones who live.” That’s the one that her and Rick use back and forth.

My Desert Island Films

Probably the first Coming to America—talk about quotable, oh my God—

My Guilty Pleasure

I don’t really watch reality shows much unless they’ve got to do with real estate, because I’m always interested in real estate. I watched that one of the women in Tampa [Selling Tampa]. I mean, it had its dramas, but I’m really actually watching them for the real estate information. I don’t feel guilty about it though.

I have watched a lot of HGTV because I’m really into home design, and I’m really into real estate. I feel it’s very constructive. I’m seeing people figure out their lives. Sometimes I’m getting creative ideas for my own reno. I enjoy it.

Who’d Play Me In My Biopic

Oh God, there’s no need for a biopic of my life. I’m always thinking about the sort of things I could write to give younger Black women a chance to shine. That’s how my brain works. All my plays have Black female protagonists and I’m always looking, like, ‘Where can I find her? What can I write that allows all that talent out there that don’t get their shot something to shine with?’ That’s kind of how my brain works. I don’t really think about, ‘OK, now what actor could play me?’ That’s completely nuts. I really have never thought about this. ★

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 15

Jerry Maguire, Dirty Dancing. The first Bad Boys. Those are the ones that come to my mind.

The Avengers

Selling Tampa

Maya Angelou

Coming to America

Dirty Dancing

Jerry Maguire

THE POWER of THE HOUND DOG

16 DEADLINE.COM AWARDSLINE

TAKING ON THE STORY of ONE of ROCK’N’ROLL’S GREATEST ICONS, ELVIS DIRECTOR Baz Luhrmann FOUND a REMARKABLE NEW STAR in Austin Butler AND RESTORED to PRESLEY’S FAMILY THE REAL STORY of THE MAN THEY KNEW AND LOVED. HE TELLS Antonia Blyth WHY IT WAS NOW or NEVER …

BAZ LUHRMANN PHOTOGRAPHED EXCLUSIVELY FOR DEADLINE BY JOSH TELLES

BAZ LUHRMANN PHOTOGRAPHED EXCLUSIVELY FOR DEADLINE BY JOSH TELLES

the night BAZ LUHRMANN premiered his film

Elvis at the Cannes Film Festival, all eyes were on Priscilla Presley. She had turned 77 the day before, and in the 45 years since her former husband’s death, she’d suffered many cartoonish caricatures and lame imitations of the man she loved. But that night, as the credits rolled, she cried.

Luhrmann was relieved; after all, Presley’s blessing wasn’t something the director took for granted. “I really mean this with great respect, because now we’re like family,” he says, “but she got a little bit vocal about her doubts. She said, ‘I don’t know, this film could be crazy. Baz can be wackadoo. And how can this skinny kid play Elvis?’”

The “kid” she referred to was Austin Butler. And her concern was understandable. How could she trust anyone to depict the man she loved; the tortured and brilliant artist who changed music history? He was a man both complex and self-destructive, with a huge, fragile heart. As Luhrmann says, “Elvis had become wallpaper. He was sort of a Halloween costume. But to his family, he was always a husband, a father, a grandfather and a person.”

On top of that, Luhrmann wasn’t planning some puff piece of cinema about a beloved icon. Instead, he sought to look behind the velvet curtain. “There were things that were going to be difficult for them to see about Elvis, but they were also going to see the humanity and true spirituality of him, which was the most important thing.”

After seeing the film, however, Presley wrote Luhrmann a letter. “I won’t share all of it,” he says, “but the key thing she said was, ‘My whole life I’ve had to put up with people impersonating my husband, and I don’t know how that boy did it, but every move, every wink... If my husband was here, he’d say, ‘Hot damn, you are me.’”

and physical health, until in 1977, when the 42-year-old Elvis—the bestselling solo music artist of all time—died of a heart attack, likely caused by his reliance on barbiturates.

Says Luhrmann, “The Colonel represents the great sell in America, and this therefore made it about America: the sale of the soul, the artist and the ringmaster.”

Surprisingly, when producer Gail Berman first approached Luhrmann about an Elvis project, he hadn’t been sure. “She’d managed to get the rights to the estate, and she said, ‘I’ve got this one idea.’ I said, ‘Well, what is it?’ She says, ‘It’s you.’ And she never gave up. Then, when I told her my idea about the Colonel, she dogged me even more about it.”

Having cracked the subtext, there was still a long way to go: where do you find an actor with the range to play that kind of icon? Luhrmann originally set about workshopping Harry Styles and Miles Teller for the part. But then came this former Disney actor, Austin Butler, for whom getting the role felt almost tinged by magical intervention.

“I had never heard it before in my life,” Butler says, “but in the month prior to hearing about Baz making the film, an Elvis Christmas song was on the radio, and I was kind of just goofing around, singing along to it. And my friend said, ‘You’ve got to play Elvis.’ But it was such a long shot, I just laughed and pushed it to the side. And then a couple of weeks later I was playing the piano, and my friend said, ‘I’m serious. You’ve got to figure out how you can get the rights to maybe write an Elvis film or something.’ I said, ‘That’d be amazing, but there’s no way that that’s going to happen.’”

A week later, his agent called and told him about Luhrmann’s film.

“Well, immediately I got chills,” Butler says.“Because of the synchronicity of it all, I thought, ‘I got to just give it everything I got.’ So, I started prepping from that day as though I was going to be making the movie.”

The first thing he did was send Luhrmann a self-tape. “It came out of this detail that I learned about Elvis,” Butler says, “about his mom, who passed away when he was 23. That’s how old I was when my mom died, so I ended up filming this tape that came out of a nightmare that my mom was dying again. It was an emotion of such deep pain. It kind of stripped away the icon of him, or the caricature of him, and it just made him so human.”

This was precisely the depth of Elvis that Luhrmann sought, and Butler was so right for the role that Luhrmann doesn’t even recall offering it to him. “I just remember the moment he walked in,” he says. “Then one day we made the movie.”

Luhrmann had originally planned to have a voice impersonator perform as the young Elvis, because he didn’t have the rights to use those original recordings. Nevertheless, he asked Butler if he could sing. “Austin said, ‘Well, I don’t really sing but I’ve practiced one Elvis song… ’” He pauses. “I’ve still got it on video. I mean, when you hear him sing, it’s crazy. You cannot believe. It’s spinetingling. We just started riffing, and hours would go by.”

BAZ LUHRMANN likes to live his movies, and Elvis was no different: in the course of making it, the Australian moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he visited Graceland, Elvis’s home, took a dive deep into the singer’s archives, and even found the man who had been with Elvis on the day he discovered the power of Gospel music.

His mission was to show us the lost boy behind the mask, but he would frame it as “a canvas to explore America”—and crucial to that was the relationship between Elvis and his manager, Colonel Tom Parker (played by Tom Hanks in the movie). A former carny, Parker used both financial and coercive control to line his own pockets, while depleting the artist’s mental

Butler returns the praise, describing Luhrmann as a great collaborator. “Baz has this extraordinary quality where he doesn’t have a barrier between life and art,” he says. “He lives the art life. David Lynch talks about that, and I think Baz is very similar: there’s this never-ending poetry of the art, and you see how it flows into his life and vice versa. So that’s an amazing quality to be around, because you don’t feel like you’re ever breaking into something else. The two are one. And it’s also a way that

really love

work.”

18 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

I

to

“In the case of my movie, it’s basically the SELLING OF THE SOUL . It’s talent versus promotion, really.”

HUGH STEWART/KANE SKENNAR/WARNER BROS./COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

Finding the right actor to play Colonel Parker was equally fortuitous. Casting Tom Hanks so severely against type would only serve to highlight Luhrmann’s message: how, as with Elvis, a star can be constrained by audience expectations. He says of Hanks, “Once you start to be something avuncular, everybody wants that tune from you, a riff on that part of you as a performer. My joy is finding actors and helping them play a tune no one’s ever heard.”

He recalls that Hanks came on board shockingly fast. “An actor like that, to get them to do a large role like that, could take you a month of talking and convincing and cajoling. I went in to see him at Playtone, and I said, ‘Colonel Tom Parker’s like a clown with a chainsaw.’ I had a video of Parker, and I had all these props to start convincing Tom to do it. I never got the video out. He stopped me in the middle of it. He talked a bit about the character, and he went, ‘Well, if you want me, I’m your guy.’ It must’ve taken 20 minutes.”

Luhrmann’s theory as to why Hanks was so sold on the sinister Svengali role is this: “I think he’d got to such a place in his life that he knew by playing Colonel Tom Parker he would have an extra level of distastefulness from his fanbase, because it’s a bit like your favorite dad turning out to be corrupt. I think he wanted to take that step and break the expectations, because he’s truly one of the great actors of all time.”

Significantly, Luhrmann uses the Colonel’s point of view to frame the movie, a device he compares to the 1984 Miloš Forman-directed Amadeus , in which the story appears to be led by the ill-fated Mozart, when in fact it’s the twisted and jealous Salieri who tells the tale.

“It’s not Amadeus’s story,” Luhrmann says. “Salieri is saying, ‘So let me

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 19

From top: Baz Luhrmann and Austin Butler; Luhrmann with Butler and Olivia DeJonge, who plays Priscilla; Butler with Helen Thomson, who plays Elvis’s mother Gladys.

get this right, God. I was chaste. I made a deal with you to give me the gift of music. And I’m king. I’m loved. And then you go and put genius in that little pig? How’s that fair?’ And then you have the preposterous conceit in that movie, like, ‘Right, I’m going to wear a mask and get Mozart to write the Requiem to kill him.’ Now, you have to have a stupid idea like that so that you can explore the bigger idea, which is, in that case, jealousy. In the case of my movie, it’s basically the selling of the soul. It’s talent versus promotion, really.”

So now he had the theme, the cast and the dramatic tension. But at the heart of all of Luhrmann’s films, there’s always a love story. And Elvis’s is not the one you might expect.

“Very early on,” says Luhrmann, “a young guy working with me on the music said, ‘Look, I really like what we are doing, but every movie you’ve made has had this great romance in it. And you’ve got Priscilla in it and the Colonel. Is the romance really the Colonel and Elvis?’ And I went, ‘Well, Priscilla, absolutely. The Colonel and Elvis? Yes.’”

But now, looking back, Luhrmann sees that it’s something else. “I’ve just realized, the true love story of Elvis, and the way it fits into the oeuvre, is between the audience and Elvis. It’s actually about his addiction to this love: the more you get, the less love you actually feel. It’s a destructive love. Because in the end, Elvis Presley is not that child who runs around and just can naturally sing and everyone goes, ‘Oh, you’re great.’ He keeps developing a character, and then, at some point, he can’t take that character, the

mask, off. But he has that addiction to the audience, and the audience’s complete need for their icons to stay eternally young, to do another album, another song, another movie… ”

IN TRYING TO FIGURE OUT the man under the shades and the rhinestone jumpsuits, Luhrmann found an extraordinarily talented, deeply spiritual person who spent his life trying to mitigate old pain. The film takes us back to Elvis’s beginnings in Tupelo, Mississippi, and later, Memphis, seeing the hardship of his home life. “There’s a big hole in his heart from childhood,” says Luhrmann, “from the shame of his father going to jail, from being in one of the white houses in the Black community, all of that. He’s trying to mend his life constantly, trying to be liked and getting people to like each other. And ultimately, that’s going to end in self-destruction.”

There’s an important scene where a very young Elvis ventures into a Gospel service with a friend, and the friend instinctively tries to pull him back, as though they don’t belong there. But Elvis is captivated, and the preacher says, “Leave him be, he’s with the spirit.”

That friend was Sam Bell, and, unbelievably, while living in Memphis, Luhrmann turned investigative reporter and tracked Bell down, getting that story firsthand.

“One of the family members knew of him,” he recalls. “We got an address.

20 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

COLLECTION

WARNER BROS./COURTESY EVERETT

I sent a FedEx. Nothing. We drive around to the house. It’s raining. And I could see the FedEx is wet from three days of rain. It hasn’t been touched. And the house looks pretty unused. So, I said, ‘Look, he’s not here.’ And one of the young guys says, ‘So let me get this right, we’ve come all the way to Tupelo, and you’re not going to get out of the car?’ I get out the car, there were cobwebs around the door. I thought, ‘Well, he’s clearly passed.’ And then the same young guy said, ‘We’ll go round the back, then.’ I’m like, ‘Don’t get arrested. I’m Baz the coward.’ Unbelievably this older lady comes out. I said, ‘I’m looking for Sam Bell.’ She says, ‘Yes, I’m his wife. He’s been in hospital for six months, but he’s coming out next week.’”

Bell was a veritable goldmine. “Sam told me a whole lot, actually. I mean, there’s more than I put in there about how he and this kid called Smokey used to fight all the time. And Elvis was a bit of a story maker-upper because he was so embarrassed about the fact that his dad had been off in jail. Sam said, ‘My grandparents adored him. He called them sir and ma’am. No white person in those days, man, woman, or child ever said that to my grandparents.’ They just thought he was the most magical, unusual, sweet and vulnerable, but kind of cocky kid they’d ever met.”

Bell passed away in the fall of 2021. “The revelations were so authentic,”

Luhrmann says. “And he never asked for money. He just told the stories.”

Luhrmann thought a lot about them, and the pain that dogged Elvis. He sees it as a throughline to a universal human experience: the need to fill the emptiness, to manage shame, to love and be loved.

“That’s what the Greeks call pothos,” he says, “and that is, the more love that you seek that’s not internal, the more adoration you need. It’s a drug. [Overcoming it] is a life’s work. And you probably don’t start to deal with that until you’re at least 40. Because before 40, you’re going, ‘Am I someone?’ And you’re just so focused on getting it. And then when you get it, you’re like, ‘Hang on, I thought this would fix things. No. Shit. Well, how do I fix things?’ The external thing probably helps you a lot because it’s selfmedication of a feeling of insecurity and not being good enough. I mean, we see them, they’re all poster boys for it, whether it’s Michael Jackson or Napoleon. They just keep going, they keep pursuing some impossible goal that ultimately destroys them.”

There’s some footage of Elvis from the very last time he performed on camera. He’s singing “Unchained Melody”, and two years before he shot the movie Luhrmann knew he wanted to use it. “He sings the best he ever sings,” Luhrmann says. “It’s so moving that that’s the death scene. That’s the farewell.” But Authentic Brands Group, who control the licensing and merchandising rights to Elvis Presley, did not want it to be shown.

Fortunately, Gail Berman came to the rescue and persuaded them to agree. Luhrmann says, “They actually said, ‘Look, we trust you so much if

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 21

Clockwise from left: Butler as Elvis singing in Memphis; Chaydon Jay as a young Elvis inspired by a Gospel revival meeting; Elvis on the Vegas stage.

you really believe that. But we’re scared of it because Elvis is so unattractive in it.’ He’s discombobulated. He can hardly put two words together. I said, ‘Well, if you don’t want to do it, I’ll get Austin to do it.’”

Butler came through. “Unbelievably, he just absolutely studied it and channeled it, even in the costume test,” Luhrmann says. But Luhrmann knew he still wanted to follow the biopic trope of showing the real artist at the end. So, he cut from Butler’s version to the original. “We knew we had an emotional beat-change; we knew we really had something.”

Says Lurhmann, “There’s a moment when Elvis is singing the song and he looks to the audience and he smiles like a little boy: ‘Am I doing good? Am I good?’ And you realize that there’s still a little boy in there trying to make up for a dad going to jail, trying to please and be loved, and have people love each other. It’s so childlike. And then we cut to the real Elvis. I mean, we could have run through with Austin, but I knew we were going to miss the really important final thing: Austin’s humanized Elvis in a way that I don’t think Elvis has been humanized for so long. You have to remind people that it’s OK that his body was corrupt and all the discombobulation with the drugs. Inside was still this beautiful kid who just wanted to love and be loved in return.”

The Lost King

Five fast facts that Baz Lurhmann would like to share…

There are five things that—relentlessly— people are on at me about. Here’s a quick list:

1.

There isn’t a fourhour version. I have four hours of material.

2.

I will—not now, but in a couple of years—do some sort

of extended version of Elvis that will let you see more of the performance, because Austin Butler’s actual performance in the movie is on another level. There’s footage that people who like the movie should see, because they deserve it.

3.

I did discover extra footage from the two big documentaries, Elvis on Tour (1972) and This is Elvis (1981), out of the salt mines. You have

to have money to find them.

4.

I will do what I can, when I can, to try and make sure that that those documentaries are reexamined and that some of the material that’s not in there is in there. Again, I will do what I can.

5.

Finally, just remember I don’t own all these things. I’m not a king who just says, “Let there be Elvis on Tour: The Sequel.”

A Little More Conversation…

Baz Lurhrmann takes a walk through his 30-year career in film

The day before this retrospective interview, Elvis director Baz Luhrmann was approached by a super-fan. “The guy was so nervous,” he recalls, smiling. “And it reminded me of what movies meant to me when I was younger. Like Saturday Night Fever or Apocalypse Now: those two movies were everything to me. I’ll never be able to get those movies out of my DNA, which is why my films tend to be like Saturday Night Fever musicals made at the scale of Apocalypse Now,” he laughs. “Apocalypse Now: The Musical, anyone?”

Don’t rule it out. Here, he looks back on 30 years of filmmaking and the steps that led from a low-budget feel-good romcom set in the boondocks to a blockbuster biopic of the king of rock’n’roll…

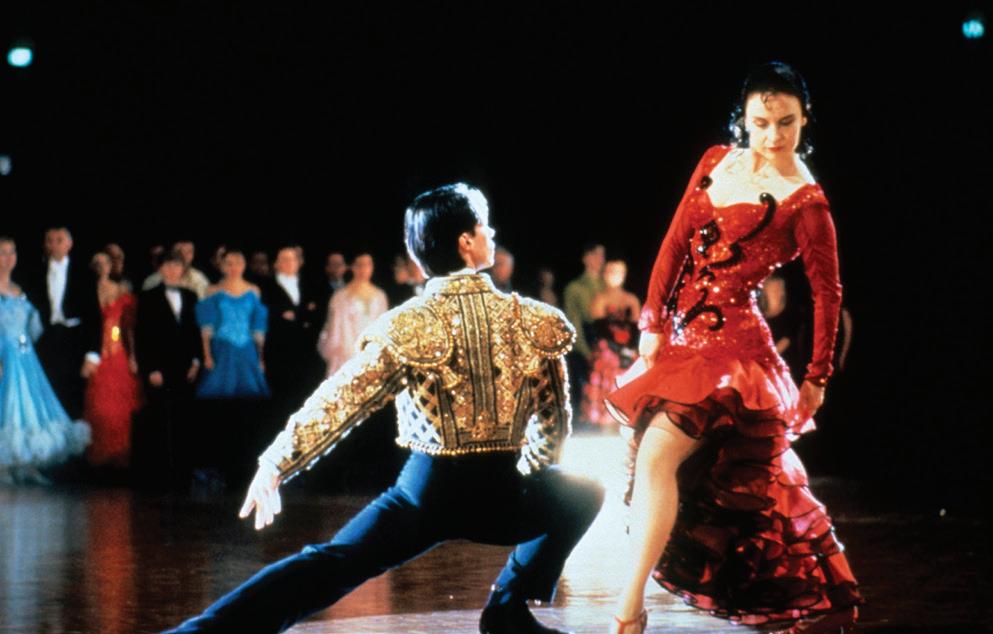

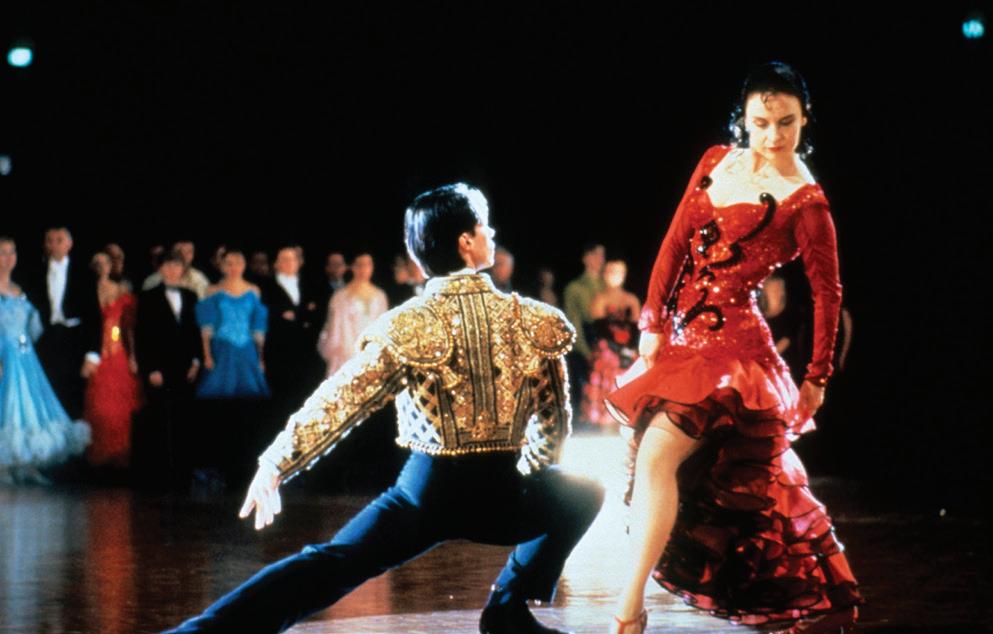

Strictly Ballroom (1992)

A rebellious young ballroom dancer defies the rules of the Australian Dancing Federation in the hopes of winning a major championship.

I come from an acting-teaching background, and Strictly Ballroom was born while I was at drama school. We were taught how to create collaborative environments and how to make our own work. Strictly Ballroom was a work that I did based on a primary Greek myth: the idea of triumph over oppression, and also the myth of the ugly duckling. I had this idea of placing it in a world that I understood, and I understood the world of ballroom dancing very well because I grew up in it, in this tiny country town in New South Wales. I devised it with a group of actors; I’d set out the architecture of the story and I’d come in with the actors every day. The original show was 20 minutes long.

After I graduated, the school was invited to a drama festival behind the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia, which was then just as Glasnost was hitting. We thought were going to be laughed out of the Soviet Union. I used to watch the other kids rehearsing; they’d be doing Chekhov’s The Seagull, and there we were with our funny ballroom-dancing play. But there

was this underlying Brechtian message in the play, we used to actually turn to the audience and go, “Fuck the Federation!” and there were recordings of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher while we were changing into our Latin costumes. At the end of the show, there was a 40-minute standing ovation. They invaded the stage, all the satellite countries, because they reacted to the metaphor of oppression.

Years later, a guy called Ted Albert saw a longer version I did with my theater company. He had a band called AC/DC. You might have heard of them. He wanted to start a film company and he tried to buy the rights, and I said, “No, I’m going to direct it.” He said, “All right,” so I developed the script and got my old friend Craig Pearce to work with me. We were about to be green-lit, and Ted died, very tragically. The film was over, but then Ted’s wife Antoinette stepped in. We defied all the odds, just like the movie.

The film screened in Cannes, at midnight, and a large crowd pressed in on us. I’d never had that before. A security guard reached in and grabbed me. He dragged me through the crowd as they followed us down the Croisette and he said, “Monsieur, from this moment on, your life will never be the same again.” Actually, he was right.

22 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

BRENDON THORNE/GETTY IMAGES/MIRAMAX/20TH CENTURY FOX/ COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

From left: Luhrmann, DeJonge, Butler and Tom Hanks at the Sydney premiere of Elvis

People might say, “Well, it’s Dirty Dancing.” Or they might say, “It’s Rocky.” But those films were also taking primary Greek myths, these against-the-system, overcoming-oppression, transformative myths, using a fun or ironic kind of language that nonetheless disarms the audience and leaves them with a resonating—whether you get it intellectually or not— larger idea. I can say that now without it sounding pretentious. But when I said that when I was 30 it sounded very pretentious.

Romeo + Juliet (1996)

William Shakespeare’s tragedy is reimagined as a post-modern urban gangster movie.

I had an overhead deal with Fox, and Romeo + Juliet was certainly not what they wanted. I think everybody wanted Strictly Ballroom 2, But that’s not how I proceed. I have these ideas or things I want to do, and one of the things I always wondered, having been a scholar of Shakespeare—he’s my go-to, really, kind of my guiding light—was the question: if Shakespeare were here, how would he make a movie?

I’d done a crazy thing once in Australia, with a girlfriend of mine, where we went into a boys’ prison—more than a reform school, a place with serious offenders—and did a radical theater company. We did some scenes from Romeo and Juliet with the boys, and I thought they’d kill us. But it was amazing

how quickly they took to the idea of playing both Romeo and Juliet.

It was unbelievably freeing for them. I only remembered that the other day.

At the time I was thinking about my next movie, I was really focused on the idea of reinventing the musical. I really thought I could do that, but I knew it was going to be quite labor-intensive.

I needed to learn more, to study musicals and learn more how to actually make or produce music.

I thought, “Well, that seems too big to do right now. Why don’t I

do something really small that I could knock off pretty quickly as a short adventure? What if Shakespeare made a movie?”

That turned into an epic journey of unimaginable proportions, with me ending up in Mexico with 19-year-old Leonardo DiCaprio and a young Claire Danes.

One day someone should make a movie about the making of that film. I mean, we had our own army. We had things like our hair and makeup person being kidnapped, and us getting him back for $2,000. (Or was it $200?) Take the church scene where the helicopter attacks Leo. It was a real helicopter shooting at him, and it blew out all the windows in the local neighborhood. We shouldn’t have been there. And it was a totally real church. The candles were real, the neon lights were real. There was no artificiality. The final shot at the end was just the camera on a rope being winched up into the ceiling. The romance of making that, plus all the difficulty and drama, was epic. So, I went from Strictly Ballroom to this epic cinematic creative adventure.

It’s ironic to me that a lot of commentators called it “MTV

Shakespeare”. I don’t mind, but MTV had nothing to do with it. I’ve never made an MTV thing in my life. What I was coming at was the way Shakespeare would do high and low comedy to disarm you. He would then slash that by flipping to high tragedy. I’m alright with it, but people back in the day would just say, “It’s bonkers.” But it’s prevailed, and it’s prevailed because there’s a method and process to the madness, if that makes sense.

I can give you an example: if you look at Romeo + Juliet, you’ll see there’s no actual objects in there that date it. At some point we were going to maybe have rollerblades and a Sony Walkman, but I knew that would date it. The cars are not dateable, the clothes are not dateable. That’s why it’s so profoundly copied. Even now, 25 years later, it’s still copied in fashion because it has its own world. But even in Strictly Ballroom, you can’t exactly tell if it’s the ’80s or the early ’90s. It’s slightly timeless. I build my films to move through time and geography, and mostly I build them for the future.

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 23

Strictly Ballroom

Romeo + Juliet

Moulin Rouge! (2001)

In 1899, a young English composer becomes infatuated with a beautiful cabaret singer at the famous Parisian nightclub.

If I was being honest with myself now, if I was self-examining—which is something I’ve often avoided doing, for good reasons—I’d say that yes, the cinematic ambition definitely did grow with Moulin Rouge!. I perhaps instinctively thought that to crack the code of the modern musical was too much of a leap after Strictly Ballroom. But to look at the modern language for Shakespeare? Achievable.

But then I went back to it. If you dig into the history of musicals, you see they have a language specific to their time and place. So in the ’30s, something like Top Hat is so artificial that Fred and Ginger just say, “Let’s go to Venice,” and Venice is clearly drapes, a glass floor, plastic gondolas and the orchestra just bursts out of nowhere. When you get to the ’60s you get The Sound of Music, and it’s slightly more realistic: Julie Andrews is at least outdoors on a hilltop, and there’s a whiff of Nazis in it. You get to the ’70s, and that’s a much more realist period. They’re doing ironic takes, like Grease, on

how musicals were done in the ’50s, or there’s Cabaret, where we’ve got a Greek chorus commenting on musical numbers that are done on stage, and this time the Nazis are actually terrifying. Each period has a way of connecting the audience to a set of rules that make a musical, and that’s what I was looking for with Moulin Rouge!

George Lucas has always been so supportive. We were talking the other day about “immaculate reality”, the idea that if you create worlds, or a cinema language that’s all your own, then immaculate reality means that the rules within that world—your rules— have to be totally worked out. Even if the audience can’t pick up on them, you have to totally know them and stick to them so they’re able to buy into the world you’ve created. The mechanics in the beginning of Moulin Rouge! are meant to challenge the audience to sign on with that immaculate reality. After that, it’s meant to assault you through sound and humor and rhythm so that you surrender your intellect and hopefully feel, by the end, that your intellect has a response that lingers. But your emotional response is the first thing we’re trying to shake you down on. Guillermo del Toro said a great

thing. He said it’s like a heist. It’s like a heist on your emotions. Certainly Moulin Rouge! defied a lot of odds. Before we finished it, SNL heard there was this period musical that had ’70s numbers in it, so they did a send-up with Will Ferrell in a 19th-century costume proclaiming, “Everybody… was … KUNG FU FIGHTING!” It was hilarious! You can’t believe now just how preposterous the idea of the musical being reinvented was and how crazy it seemed what we were doing. Yet there’s no doubt about it, it caused a lot of controversy. I mean, Romeo + Juliet did cause a bit, but the feeling there was, “It’s all pop.”

I remember the opening night in Cannes. I was with Francis Ford Coppola when the reviews came in from Time magazine’s critics: Richard Corliss’s said, “It’s the best film of the year,” and then Richard Schickel’s came in and said, “It’s the worst film of the year.” That kind of controversy just fueled it.

In the end a lot of people saw it. But everyone forgets that the international rollout of Moulin Rouge! happened during 9/11. Just recently a father brought two young girls to meet me, they were twins, and they were in their 20s. They were staring at me really intensely. They were French, and I thought, “Maybe they don’t understand what I’m saying.” Afterwards, the father— who was a cinephile, actually—said, “You don’t understand. When 9/11 happened, they were eight years old. They watched Moulin Rouge! every day. They were upset, but they hid in Moulin Rouge!.” They’re filmmakers themselves now, by the way. But there seems to be a pattern. I’ve noticed a whole generation of people in their 20s that Moulin Rouge! became a kind of refuge for.

Australia (2008)

On the eve of the Second World War, a British noblewoman inherits a huge cattle station in northern Australia and then must fight to protect it.

24 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

Moulin Rouge!

20TH CENTURY FOX/WARNER BROS./COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

Australia

I do a whole lot of other things in between films, because I’m always looking for creative adventure. When you do one of these movies, they take forever, and I live them. I absolutely live the movies. The research takes years, and creating them takes years, so I want to make sure it’s something that’s going to keep me getting up every day. After Moulin Rouge! I started to get such noise, like, “This is his brand, this guy makes this kind of movie.” Now, I’ve always admired artists like David Bowie, or Picasso, or Dylan when he went electric. They flip what the audience wants from them, and they flip it because they have another note on their instrument that they want to explore.

For a while I was doing Alexander the Great, and it was a giant journey. I was so down the road on that. It was with Leonardo DiCaprio again, and Mel Gibson, and I was working with Dino De Laurentiis. At one stage Martin Scorsese was involved, and we built studios in Morocco. It was such an adventure, but there came a time when, for personal reasons, I really couldn’t continue with it.

So, instead, I did Australia. I wanted to sort of flip—if you like, in a postmodern way—Gone with the Wind and use it as a sweeping pastoral epic. But I also wanted to address, very deeply, the personal issue of the stolen generation in Australia. I always felt that this was something that only so-called “serious films” had been made about. Small films. But how do you take such a difficult subject in a way that reaches a broader and wider audience? That was my real motivation. Taking a traditional, old-fashioned form, the sweeping epic, and flipping the perspective to that of the indigenous child.

I was really living it, living in north Australia and working with some of our country’s great writers, like Richard Flanagan, learning about the stolen generation. As a filmmaking experience, it was by far the most fraught. We were hit by equine flu. I went to the desert to shoot, and it rained for

the first time in 150 years, so I had a grass-covered desert. It nearly killed me, but I wouldn’t give a day of it up at all. Looking at it now, it’s probably the only thing I’ve done where there’s no confetti or fireworks. Actually, there might be, but if there’s no fireworks, there’s definitely a big rainstorm.

It’s weird because in America it didn’t play at all. It’s the only film I’ve had that didn’t really open in America. Everything else has played there, but it’s the biggest film I’ve ever had in Europe, and it still is. It’s still my number one movie in France and Spain, and I’m still not sure why. I was in Paris a couple days ago. They really lean into Australia, and they talk about it like it’s this masterful epic.

I’m like, “Hey, isn’t it the loathed child?” But it’s the number two highest grossing Australian film of all time, so somebody saw it.

The Great Gatsby (2013)

An adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel about a Long Island banker who becomes involved with his enigmatic, party-throwing millionaire neighbor.

After these large films, I go on what I call a methadone program, because I’m so high on adrenaline

that I allow myself a period of time where I’m sort of debriefing myself. I usually go off on my own for a couple of weeks, and after Moulin Rouge!, I went on the Trans-Siberian Express. Which, by the way, is not the Orient Express. Don’t get confused, this was not some beautiful first-class place where they bring you breakfast on a silver tray, it was a rattly tin box where a babushka would take a rubber hose, hand it to you and say, “Go shower!”

I had this new invention called the iPod. It had two speakers and on it were two recorded books. I don’t remember what the other was, but one was The Great Gatsby. I got out the red wine and I put it on. By the morning I was so enraptured in that world that I wanted to live in it. I started to pursue the rights, and I did Australia in between because it took that long to find a way of getting them.

Then there was the 2008 economic crash. It came after the Australia shoot, just as it does at the end of Gatsby : there’s the Roaring ’20s and then there’s the Great Depression. I thought, “Wow, this story speaks to now.” Which, I have to say, is always a crucial deciding factor in any work I make: can it speak to where we are?

Today, more than even when it opened, it’s got not just a fanbase,

but teachers come up to me and say, “We show your Gatsby because young audiences understand not just what that time was like,”— and this is what I set out to do— ”but what it might have felt like.” I mean, it may be a quiet narrative, but it’s about the Roaring ’20s, by a brash, young novelist who was living in that crazy, far-out age. If you look at footage from the ’20s, they weren’t all dressed in white. It was noisy, it was colorful, and it was in your face. I mean, Fitzgerald put what was considered at the time to be a confronting kind of black street music called jazz into the novel, so Jay-Z and I decided to turn that into hip-hop. It caused a lot of dissension, but we did it, and it worked.

How I feel about it is how I feel about all the movies: they’re my children. Some are loved more at birth than others. Some are loathed by commentators, but they’ve all gone on to have relationships—mature relationships— with long-standing audiences. In the end, I made a choice a long time ago. If you’re going to make things that are very personal or out of the box, there’s only one relationship that really counts, and that’s the relationship with the audience and with yourself.

★

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 25

The Great Gatsby

BY DAMON WISE

Following Swiss Army Man , in which Daniel Radcliffe played a flatulent corpse, was always going to be hard for the Daniels, AKA Daniel Scheinert and Dan Kwan. But not only did they do it, with a crazy fantasy about a Chinese American mom—a never-better Michelle Yeoh—who unlocks the secrets of the universe, they’re also looking at serious awards season buzz for their direction, screenplay and cast. The directors are obviously flattered, but they have a favor to ask. “You’re not allowed to root for our film unless you go see all the other ones,” Scheinert says. “Particularly in a theater. They’re so good and so much fun in a theater.”

Cast your mind back to when the film premiered at SXSW. Were you nervous or did you know what you had?

DANIEL SCHEINERT: I think we knew. We were less nervous than Swiss Army Man because we had a distributor, we knew that the movie had crowd-pleasing qualities, and that SXSW is a very friendly place

where we’ve screened a lot of our very weird movies over the years. So, we were like, OK, this audience will be friendlier than some festivals to the weirdness. But the reception still humbled us and freaked us out. And it was the first time we got a taste of just how much people resonated with the emotional side of the movie, not just the action.

26 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE A24/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

The DANIELS The directing duo discuss the hive mind that gave us Everything Everywhere All At Once

★ ★ ★ ★ ★

The Best Of 2022 | Directors

It’s a film about levels, but it also works on many levels: there’s a level of spectacle, but there’s also a lot of emotion and philosophy, which is the most surprising element. How did you approach such a big story?

DAN KWAN: We’ve been directing together for 10 years, and we’ve slowly learned that we love to balance all those things. I don’t think we’d be happy if we only made a fun action movie, and I don’t think we’d be happy if we only made a philosophical treatise. And so, every time we come up with an idea, we always, in the back of our minds, know we have to pair it with these other things so that we get this beautiful constellation effect.

Is this an idea that you could have had independently of each other, or is this very much a product of the Daniels?

SCHEINERT: Totally. We always say we would make completely different movies if we were by ourselves, but in this case, it started with a silly idea Dan had and then he pitched it to me. I don’t like science fiction if it doesn’t acknowledge the philosophical repercussions of its premise—if it just brushes over that and it’s just fun—so I pushed back, and we stumbled into the bleak, meaningless direction the story might go. I don’t know which of us wanted it to be Chinese American first, but I do think that our internal conversations had made us hungry to explore that because our longtime producer is Chinese American, and Dan is. So, it’s definitely through conversation that the idea took shape. We’re always stress-testing each other’s ideas, being each other’s first sounding board.

How important was it to have a middle-aged woman as the center? Was that always the plan?

SCHEINERT: It was always our parents’ generation.

KWAN: Yeah. We always knew the film was going to be about generations, that gap that happens with every generation, because it felt like a really perfect way to explore

the multiverse and the way that we were trying to use the multiverse as a proxy for the internet, and how it’s really divided us and our own parents. But then the fact that it was about a mother came later. As we were exploring draft after draft, we slowly realized how much easier it was for us to write to our mothers. We have very strong-willed, interesting mothers who have... left an impression on us. And so, writing to that just felt way more personal and way more interesting and something that we talk about a lot. It became a movie that we hadn’t seen before.

Putting my mom in The Matrix was a very funny concept that, once we pitched it in those terms, we started to really get excited.

Do you have a particular axe to grind with the IRS? It’s something that upsets a lot of people at this time of year.

SCHEINERT: We’re not good at taxes, and we know that there’s this prejudice against the IRS, so we really wanted to tap into that [laughs]. But we do not have an axe to grind with them. We think they need more financing. We think Americans need to pay their fair share of taxes. We think it’s a hard job. They’re just underfunded, and we’ve got to make our tax code go after the billionaires.

KWAN: We wanted the biggest challenge at the end of the film not to be a bad guy with a big weapon or something like that. The hardest challenge to us was an empathy challenge. And so we thought, ‘OK,

who would it be hardest to empathize with? The awful, crotchety auditor.’ And so that felt like a really fun thing to play with.

The action scenes are tremendous. What’s the secret to directing kung fu?

SCHEINERT: You have to just rip off Hong Kong movies and hire the right people [laughs]. But from the very beginning, it was something we were very excited to do. We’ve always loved that kind of cinema and we’ve gotten to do little bits of it in our career.

KWAN: For both of us, how we look at filmmaking is, oddly enough, through an action movie lens. That’s what I grew up on. My favorite movies, growing up, were the Hong Kong action movies and James Cameron’s action films. Terminator 2 was one of my favorite movies of all time when I was five years old. And so even when, before we started actively making this film, our whole career we’ve been shooting music videos kind of like they’re action films.

There are so many universes, so many worlds. Were there any that didn’t make the cut?

SCHEINERT: There’s a lot that we wrote in the various drafts, and it took us a while to figure out, “What are the rules of what should stay and what should go in a movie that’s trying to go for too much?” And so, we whittled it down to universes that would definitely move Michelle’s character in a new direction. But there were two; there’s two that are on the Bluray that disappeared. One where

Alpha Waymond is a pacifist and Michelle is a talking urn, and it was a universe where they talk about how this action movie was all for nothing and that war is not the answer. But the most heartbreaking one to cut, which was in every draft of the script, was a universe where you meet Spaghetti Baby Noodle Boy, which is a little talking macaroni and Michelle’s a talking spaghetti, and they talk about what it’s like to be in a world filled with pasta people. It was all puppets. We shot it, but in the test screenings, nobody responded to it.

What did your mothers think of the film?