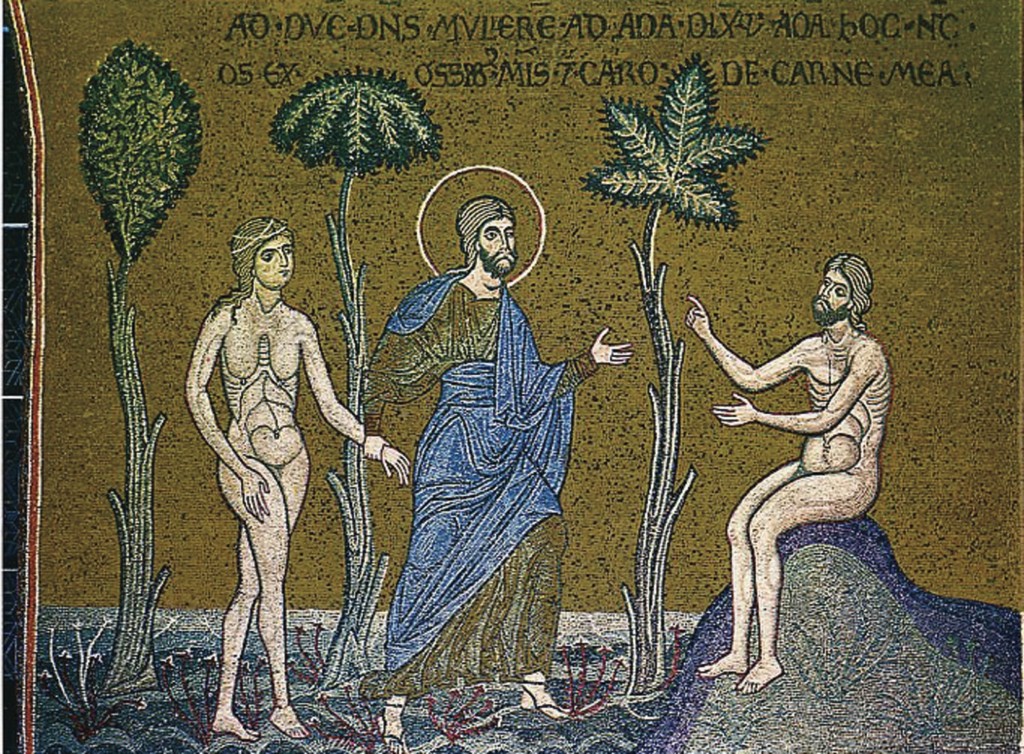

God presents Eve to Adam. Mosaic in the Cathedral of Monreale, Italy (near Palermo).

“The universal fact about marriage is not that all human persons are called to it — but rather that all human persons are called to come forth from it”

By Mary Ellen Stanford

At a press briefing during the Synod, Chicago Archbishop Blase Cupich emphasized the importance of having “an adult Catholic response to living the Christian life,” and even mentioned a retired archbishop who said he wants his tombstone to read: “I tried to treat you like adults.”1 The use of the word “adult” gave me pause here, as I wondered: is the Word of God, is the “Good News” preached by Our Lord, in fact, even for “adults”? When Jesus said, “Anyone who does not welcome the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it” (Mk 10:15), it seems He was calling all of us to embody those qualities which are natural not to adults, but to children: vulnerability, dependence, and a complete trust that their needs will be fulfilled, that the actions taken on their behalf will be for their good, whether they can clearly perceive that good or not.

Such a disposition is no doubt difficult for those adults who do not immediately perceive the Church’s teaching on marriage as “Good News.” For those Catholics who have divorced and remarried, or for those who experience same-sex attraction and long to marry someone of the same gender, the Church’s teaching often appears as bad news, as exclusion, as hurtful. So many adults understand marriage as a road to joy and personal fulfillment—how could it be that our Church teaching seems to preclude such a number from experiencing its benefits?

The answer, perhaps unsurprisingly, has to do, not with the adult, but with the child. John Paul II’s Theology of the Body, so often cited for its explication of the person-fulfilling dynamic of gift made possible through Christian marriage, holds critical insights for us here. Though John Paul extols the benefits of marriage—particularly by reason of the virtues it calls spouses to develop—he is clear that not everyone requires human marriage in order to find fulfillment. While great in dignity, marriage is not the “be-all and the end-all” — he is quick to remind us that it will pass away in the next life. The universal fact about marriage is not that all human persons are called to it—but rather that all human persons are called to come forth from it. Each one of us is touched by this one-of-a kind union of man and woman. From the first moment of human existence, the “universal fact” of all of us is that in God’s design, we were surrounded, embedded in an intimate community of persons. Why is this so?

The entrance to the institute John Paul II wanted

John Paul explains to us that man, from his earliest moments in the Creation accounts of Genesis, is seeking to understand himself and to find affirmation of that identity. Just like each one of us today, the man in Genesis is seeking to know who he is.

He begins to sense his uniqueness when God presents him with the animals; in observing and naming them, he discovers that none of them is truly a fit companion for him. Though clearly superior to them, his own identity continues to remain something of a mystery until at last the woman is presented to him by God. Upon seeing her, he famously exclaims, “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh!” (Gen 2:23). For the first time in creation, we witness an expression of joy. But what John Paul emphasizes here is that, at this moment of beholding the woman for the first time, Adam is not merely fixated on the beauty revealed through her sexual difference. We are not to paraphrase him saying, “Wow, look at you!” Rather, in recognizing their common humanity, it is almost as if Adam says, “Wow! Look at me! That’s who I am!” and his self-knowledge is perfected through her. It is precisely in encountering another, notably different from, yet in a more profound way “like,” himself that Adam more fully knows himself. In searching for an affirmation of who he is, he sees her and instinctively identifies with her. And he rejoices. The deepest human happiness and the fullest kind of self-knowledge come through community. Furthermore, John Paul notes that it is not the man alone who is affirmed in this bodily encounter with the woman. The joyful acclamation with which Adam greets Eve is as much an affirmation of her own identity as it is of his. His words are a sign that Adam is welcoming her—receiving her as a gift from the Creator—and such an acceptance communicates to her that she is a gift—that being a gift is an essential dimension of her identity. John Paul explains that she “‘discovers herself’ thanks to the fact that she has been accepted and welcomed…and thanks to the way in which she has been received by the man.”2

Such is a fundamental principle of human relationships: when a person is physically welcomed, when he is accepted by another in his fullness as a gift, only then does that person begin to understand, to know himself to be a gift; only then does he begin to grasp the fullness of his identity. Renowned retreat master Fr. Jacques Phillipe echoes this principle when he writes: “We urgently need the mediation of another’s eyes to love ourselves and accept ourselves…we need to be looked upon by someone who says, as God did through the prophet Isaiah, ‘You are precious in my eyes, and honored, and I love you.’”3 Such is the pattern of our existence from its very beginning. In the Creator’s design, new persons do not emerge from a cabbage patch or a medical lab. From the first moment of human existence, it was the Creator’s design that each of us be received into a family, an intimate, embodied community of persons—and our self-image is meant to develop and flourish in this context of a very concrete and visible love. When the Church preaches against fornication, co-habitation, divorce, or contraception, it is because each path not only fails to provide the context for receiving a person as a spiritual, physical whole, but because each further risks depriving any possible children of that stable, identity-affirming environment which is their birthright. When any aspect of this foundational community is missing—the permanence, the total giving and receiving, the encounter with parents of both sexes—there is a profound risk of a child being wounded in his identity, and crippled in his self-understanding. And yet, therein lies the crux: can adults today face the challenge the Church is putting before them? Can today’s adults—so very fixed on trying to find fulfillment through sex—accept the truth that they can survive without sex, but that children cannot thrive without the fullness of Christian marriage? One author noted that in our modern age, it seems that children are again and again being “asked to suffer, so adults won’t have their feelings hurt.”4 While adults are clamoring for the Church to stand up with the rest of the world and applaud them for their choices, these children, these “little ones” are being asked to bear the burden of such choices at odds with their own flourishing.

For the Church to ask a divorced person or a same-sex-attracted person to live chastely is to ask him or her to practice (often) heroic virtue to take a stand, to witness to the God-given claim of a child to that intimate community of persons designed for him. To live such chastity is to be a kind of martyr (in Greek a “witness”)—to put one’s own desires aside and to say to a child: You deserve more than this, and I won’t be the one to insist on my desires without considering your needs. Even in the case of a child already wounded by divorce, a parent who lives the call to chastity communicates to this child that he won’t compound the wound by a remarriage, that he won’t demand that the rest of the world forget the reality of that first union. To faithfully witness to the reality of a first marriage at the very least communicates to a child his dignity by a refusal to “replace” that parent to whom he is inextricably linked. To take such a stand, to assent to the Church’s teachings, however painful, is to trust that the Church truly looks to the good of her littlest ones, even when the rest of the world has put the feelings of adults first. Happily, such a trust is the beginning of being truly childlike.

Facebook Comments