From our November 2022 issue

The most famous campaign stunt in Maine political history is no good today. Or so, anyway, argues the man who engineered it, Christian Potholm, a Bowdoin College professor emeritus of government and the editor of the new book Bill Cohen’s 1972 Campaign for Congress: An Oral History of the Walk That Changed Maine Politics. It’s a highly readable, if fairly wonky exploration of a landmark election that found Republican Congressional hopeful William S. Cohen, a young trial lawyer and the mayor of Bangor, hitting the road for a six-week stroll across Maine, striking up sidewalk conversations and crashing in his would-be constituents’ spare rooms. As another Maine election season reaches its culmination — full of the usual TV attack ads and slick soundbites and social-media insanity — the book feels like a window on an alternate electoral universe, where campaigns are scrappy, political opponents are collegial, and politics happens on the streets rather than on screens.

“Today, with cell phones, walks would put candidates under constant visual supervision,” Potholm writes in the book’s foreword. “They would not be able to go into the woods to relieve themselves without being filmed. More importantly, today’s candidates have to spend so much time raising money, going to fundraisers, and ‘dialing for dollars’ that they wouldn’t have time to walk in the first place. . . . A walk simply cannot drive the political narrative the way it did in 1972.”

Not that Maine candidates haven’t continued to try it. Cohen, of course, won a seat representing Maine’s 2nd District in the House of Representative in 1972. He served three terms there before Mainers sent him to the Senate, in 1978, and President Bill Clinton appointed him U.S. Secretary of Defense, in 1997. But before any of that, “The Walk” had already become an offbeat political tradition in the Pine Tree State, repeated by Cohen the congressman and by Maine political hopefuls in every decade since, including future senator Olympia Snowe and governor Jock McKernan.

In the book, Potholm and co-editor Jed Lyons, a Bowdoin student and campaign staffer in ’72, talk about these and other campaigns with various veteran Maine politicos. But the meat of the book draws on conversations with former campaign staffers and Cohen himself, now 82, recalling a campaign that Lyons calls “historic for its revival of the Maine Republican Party,” which was then on the outs with voters — and the long, freewheeling walk that made it possible.

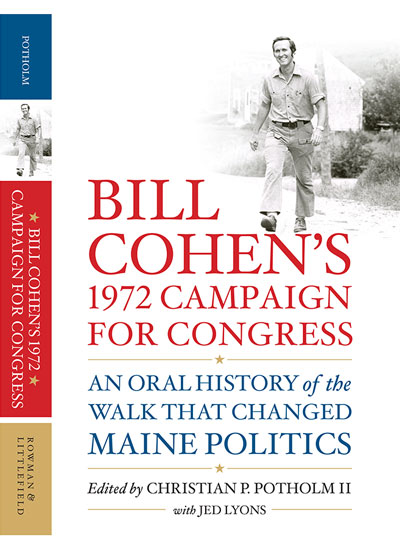

This excerpt from Bill Cohen’s 1972 Campaign for Congress: An Oral History of the Walk That Changed Maine Politics (Rowman & Littlefield; hardcover; $24.95) draws on two chapters, from conversations with Cohen, Lyons, Potholm, and Cindy Watson-Welch, a Bowdoin student in 1972 who joined the campaign field team. The text has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jed Lyons: The walk was the brainchild of Bob Loeb, who was a student at Bowdoin. He came from Chicago and knew that the Illinois governor had done a similar walk across his state, and so we decided to do the same thing in the sprawling 2nd District of Maine.

Bill Cohen: Yes, he was “Walking George Walker.” He was the governor of Illinois, and he had walked, not the entire state, but a big stretch of it, and there was also Senator Lawton Chiles from Florida. I went down to meet with Lawton Chiles. Of course, I got pushed off to a staffer. I asked how did you guys do it? He did not walk his entire state and didn’t stay overnight in someone’s home. He just walked. Those were the only two at the time, Illinois governor Walker and Lawton Chiles, as I remember.

Lyons: How did you get the audacious idea of doing a walk from one end of the state to the other, and one that would include consecutive overnights in private homes over the course of many weeks?

Chris Potholm: I thought the whole idea was to cover as much of the state during that period in the summer, when there wasn’t much campaigning. It made sense in terms of the math, and I never realized we would go beyond Houlton. But looking back on it, while it probably made the walk a lot more painful, I was adamant about Bill spending the night in a real person’s home each night.

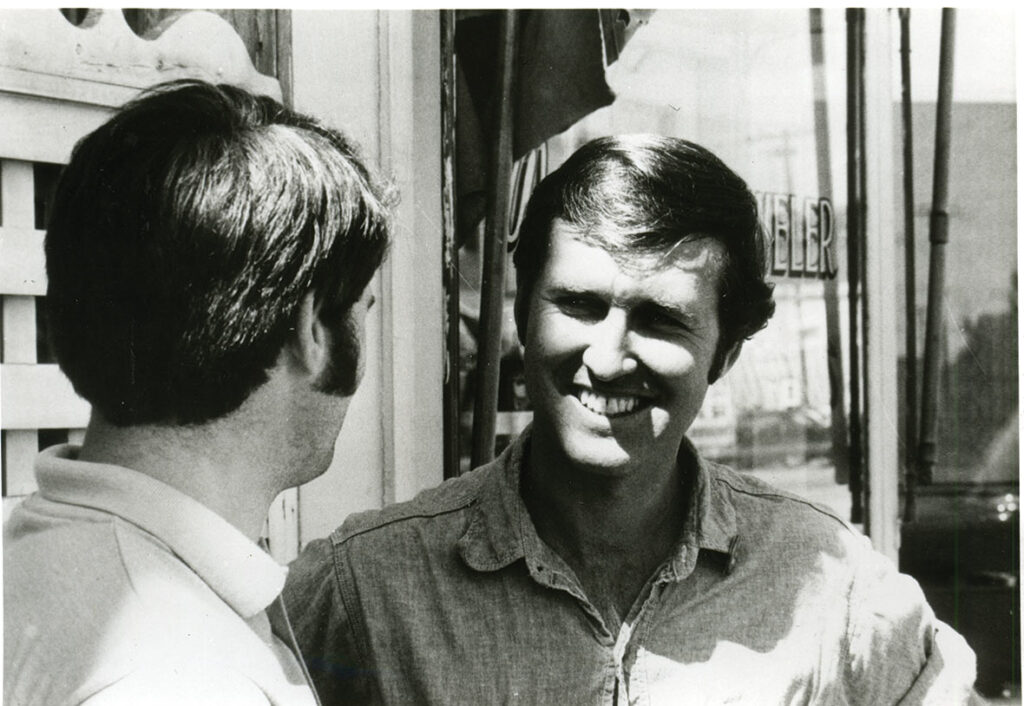

Cohen: Actually, it was really enjoyable, partly because we would stay with families that were pretty modest, on the lower end of the economic spectrum. Not always, but as we got into the Lewiston area and into the Democratic areas, it was fun for me to be able to say, “Look, I come from these roots.” If you look at the building where I was born, on the top floor of a tenement house that was filled with immigrants, I certainly could relate to these families. They might have as many as six people around a table eating, probably pasta or something comparable. And then, after the meal, they would invite their neighbors and expand from six to maybe 12 or 15 in the living room, where I could sit, either in the middle or on a sofa, and just ask them what they thought about politics. What were they looking for? How can I help if I got there? It was really connecting to them in a way that was unique, that a politician would spend the night with them, eat with their family. I knew that they would tell at least 15 more of their friends the next day, and their friends would tell 15 more.

I never felt exhausted, even though some of these meetings went on till 10 or 11 o’clock. They had to go to work, and I had to be up and ready by 6:30 to get out there and start from the spot that we marked where we had stopped the night before.

Campaign poster courtesy of Christian Potholm, photographed by Gridley Tarbell.

Cindy Watson-Welch: My role most of the time was to be a front person. I would travel a day or maybe two ahead of Bill’s destinations. I would put up signs announcing that Bill was on his way and then explain to the locals who Bill was. I would also scope out the town and the townspeople to see what was important to them for feedback for Bill. I remember one town, for example, they had a little local newspaper, and on the cover of it was a big picture of this damaged telephone booth. Everyone in the town was outraged that their only telephone booth had been vandalized. So I told Bill about that, and when he arrived in the town, he started talking about crime and vandalism and, boy, that town was united behind him immediately!

Lyons: Where did you stay while you were doing this work?

Watson-Welch: We were on a very tight budget, so basically we stayed in small motels. We sometimes had three to five of us in a room. Being the only girl, I would often get the bed (out of chivalry), and the others would share the second bed or sleep on the floor. I did do my turns on the floor, to be fair.

Lyons: So you had no budget. Did you spend your own money on your motel rooms or were you reimbursed?

Watson-Welch: The campaign paid for the hotel rooms. We pretty much were on our own for picking up meals, but the host families and others involved with the campaign would stop by with donuts or other treats.

Lyons: So our esteemed campaign chairman Professor Potholm gave you no budget other than for a fleabag hotel room shared by three people?

Potholm: Compared to today’s overbought, wildly expensive campaigns, I mean, we really did it on a shoestring. Today, you’d be eating sushi and staying in suites, with all the money washing around.

Watson-Welch: I know, but it was always interesting. I mean from one town to the next it was always something new. There were some really long afternoons in which there were very few cars going by. I think it was tempting to just have Bill hop in a car and move on to the next town, but he was determined to walk each mile. Slow days could get a little tedious. But for the most part, it was really fun.

Cohen: And we always made sure there was no cheating. The media would basically know where we stopped, and they would come out to see if we were starting from there. I never felt exhausted. I was energized by the whole experience, and it wasn’t quite the Second Coming, but it felt like that on many occasions, where people, especially in the rural areas, would sit out on their porches and wait for me to walk by. We had a rule that I would never go up and try to knock on the doors of homes. Along the walk, if people were outside, I would walk up to their driveway or on their porch, but I wouldn’t be knocking on doors and disturbing their privacy. The local newspaper would say, “Cohen is scheduled to walk here tomorrow morning,” and so people would actually be out there, some for hours, waiting for me to walk by and talk with them. So it took on a messianic feeling for me. One, they couldn’t believe that I would make that effort, and two, that I would spend time with them. So that was energizing in and of itself, and I never felt tired.

Watson-Welch: Our destination was from one point to the next point, but people would slow down, they would wave or they would look at me, or sometimes when I was in the back car, they would say, “Who’s Bill Cohen?” So yeah, I mean, he got a lot of attention that way — passersby, of course, most of the time. Sometimes, people would stop and offer him a beer or a sandwich or something like that. He actually gained 20 pounds on the walk, which is really amazing when you think he was making 20 miles a day, but every family made a feast for him. They were really happy to be hosting him and having friends come in and speak to everybody.

Cohen: My feet were hurting because of the big footwear mistakes I made at the beginning of the campaign, and even that turned out to be a political plus when I went to the hospital to have my blisters cut and then my feet taped so that I could go back out on the walk. A photo was taken of me, soaking my feet in a steel tub, that appeared in the local papers. I think there were two occasions when I had to seek medical treatment.

Lyons: I remember that you went into many shoe factories and were handed a new pair of boots. It was the last thing you wanted to see, but you gamely put them on and walked out and your feet were killing you.

Cohen: We gave them all away at the next stop. Every time we stopped in a small town, they were doing a fundraiser for a charitable cause and would ask me to donate something. I said, “Yes, my shoes.” I could afford to do that because at the time there were a number of shoe factories in Oxford County, where we had started out. We were almost the shoemaking center of the country before the massive transfer of those jobs to Asia.

I always looked forward, on the walk, to see if there were any kids playing basketball. I would ask if I could shoot baskets with them, and they would be impressed that this old guy could still shoot. And so that was part of the fun of it as well, showing off a little bit in the pickup games.

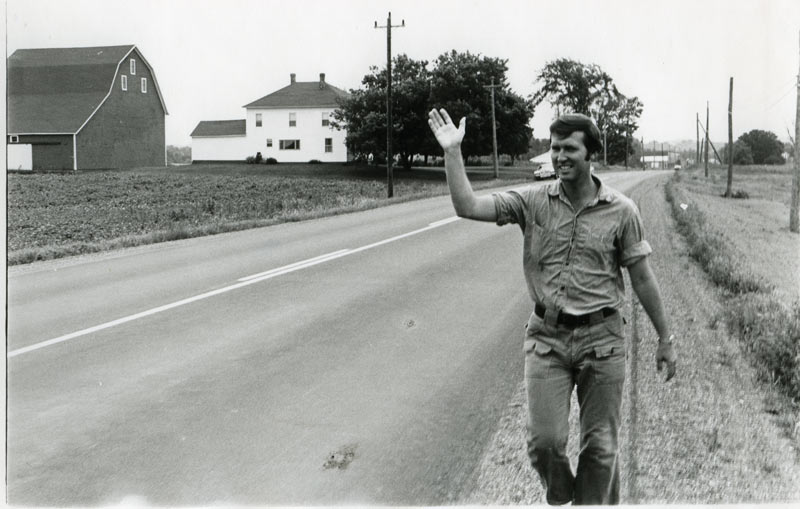

Walking was to become Cohen’s trademark. In most of his campaigns, and in many non-election years, he walked through the towns and cities he represented, talking informally with constituents. These photos capture moments during the 1972 campaign and other subsequent walks in Maine.

Beyond that, I just recall looking ahead, watching out for cars. You may recall, Chris, that was the route where the Canadian cars came flying down 70–75 miles an hour on a two-lane highway. I kept looking to make sure they weren’t getting too close. I think a couple of times people tossed bottles out of their car windows. They didn’t come close to hitting me, but it was a warning sign that not everybody was honking and waving and shouting hallelujah. I remember that walking in the rain was really dangerous because visibility is down, wipers were clicking away, and the people were still traveling pretty fast. Those were the moments I worried about the most during the walk.

I believe that it was Jane Johnson, of Houlton, who arranged for me to take part in a race at the Spud Speedway, near Presque Isle. I’m not sure at this time whether it was on the [first] walk or a year later. I had no knowledge that she had done that, so I was surprised when I arrived at the Saturday-night event. They would get these old banged-up cars, remove the interior padding, and weld the car door shut, so you had to climb through the windows to get into the car. This was not something that I was eager to do, but the organizers of the race handed me a helmet and gave me little choice. I might get injured if I entered the race or be wounded politically if I rejected their offer. They had a picture of me with a guy called “the Flying Frenchman of Madawaska,” wholookedatmeasifIwasgoingtobehis meal on the dinner table that night.

The cars had no mufflers. They were stripped down to the metal bones of the car. No dashboard and just two gears where you go from low to high very quickly. I said, “Well, okay, I guess I can do this.” There were about six or seven cars in the race, and I thought I would go to the very end of the starting line and let all of the cars pull out ahead of me and let them get ahead of me and just hang in last place. That’s not what they had in mind. They insisted that I be the lead so that the other drivers could bang me all over and ultimately push me off the track.

Every time I tried to slow down, bam! Someone smacked me from behind. Then another car hit me from the side. Bam! Two cars had me pinned on the inside and were trying to push me off the track. The fans in the stands were cheering, and it wasn’t for me! I made it around the track, I think, a couple of times and then I pulled off. They were disappointed that I wasn’t having as much fun as they were and said, “Well, you got to stay here. We want you to flag the next race.” They had kind of a plank-like structure built over the speedway, and they had me walk out on the platform and wave the flag to start the race. Unfortunately, I had to stay on the platform until the race finished. The problem was while I was up there, one of the tires came off the cars on the last curve and was bouncing toward me on the structure. I managed to retreat just in time.

I didn’t get hit by the tire, and I didn’t get turned over into a ditch on the racetrack, but this wasn’t a great idea, even though the local press played up my being a good sport.

Lyons: I remember we entered you into a fundraiser “swimathon” at the YMCA in Lewiston, and you were not happy about that either.

Cohen: I had the flu or something, and I was feeling really ill, but you said, “You gotta swim.”

Lyons: And you did. You got in a bathing suit and you swam up and down the pool and you earned money that you contributed for each lap. Being competitive, you continued to swim and swim and swim to make money for the YMCA. This was right in the middle of the walk. You were exhausted before you even got in the pool.

Cohen: Right.

Lyons: You weren’t happy with us that day.

Cohen: No, well, probably many other days too. I remember that one well.

Potholm: How about the time you two decided it was a good idea to do some politicking in the drive-in theater?

Lyons: That was in Houlton.

Cohen: The movie playing that night was Boxcar Bertha. The goal was to get there by 6 o’clock or 6:30, as the cars were coming in, and shake the hands of the drivers. Unfortunately, we didn’t get there until about 9, and it had already become dark, and we said, well okay, what do we do now, folks? And Jed said, “Well, we’re here so we might as well give it a shot.” And so I went around knocking on the steamed-up windows of the cars.

Lyons: I remember that night. We had nothing planned, no dinner at a private home or an event. And so I suggested that we go to the drive-in and meet some voters and you said, “Are you crazy?” But because we wanted to meet voters, we went, and when we got there, there were no voters to be seen.

So I suggested that you go over to a nearby car and knock on the window. You knocked on the driver-side window and there was no response. Then, all of a sudden, the backseat window comes down and the guy says, “What the hell are you doing?” and you said, “Well, I’m Cohen and I’m running for Congress,” and the rear window went right back up. We stopped by a few more cars and the same thing happened. Do you remember that?

Cohen: Oh, I do, I do, and I’ve got you to blame. That’s one of the more memorable events, Boxcar Bertha. There was also the time, I think I mentioned before, when I went into a bar. And there were two rules I talked about: Don’t go into a beauty shop where women are having their hair done. That’s a no-no, because they would scream for me to get out. That was their time and their place to become beautiful. Men are not wanted! The other rule was to never go into a bar. I had violated both rules of no beauty shops and no bars.

I was in a small town, I think it was near Lincoln, and decided to meet some of the local folks in the bar. I started walking around shaking hands, and one fellow refused to shake hands. I ordered a Coke and asked him if we had ever met. He said, yeah, without volunteering more. “Did I represent you on a legal matter?” “Yeah. You’re the son of a bitch that put me in jail!” The man was mean-looking, and I decided to finish my Coke and get the hell out before my attempt at pleasantries turned really ugly. I decided that I wouldn’t go into a bar again looking for votes. People who are drinking, usually they’re either happy or very angry, one or the other. They’re almost never happy to see a politician.

Those are two experiences that remain vivid. Also, having to watch out for farm dogs. They don’t like strangers. I managed to get nipped a couple of times, but nothing serious.

Lyons: We had a car in front of you and a car behind and a hand-painted sign that said, “Cohen Ahead, Honk and Wave.” I recall that when we were in a slow area, a quiet area, I’d go forward a day ahead to try and find the local Republican committeemen or committeewomen to help organize an event the following day when you’d be walking into town. I remember how excited people were because they knew you were coming and they were vying to be the host or hostess and have you stay overnight at their home. . . . I remember, we really got into some rural areas, and you were walking sometimes without seeing a single car for hours at a time.

Cohen: The Haynesville Woods, you may recall. That was about a 19-mile stretch where you’d see nothing but pulp trucks and blackflies. And we had to make a decision to walk that 19 miles or skip it. We decided that since I had said I was going to walk the entire district, we weren’t going to take any shortcuts. It was an unpleasant experience but it turned out that all the guys driving those pulp trucks talked to other people at rest stops and restaurants down the line, saying that they saw some crazy SOB in the woods slapping flies on his neck and face. He must really want the job.

Excerpted from Bill Cohen’s 1972 Campaign for Congress: An Oral History of the Walk that Changed Maine Politics, edited by Christian P. Potholm II, with Jed Lyons. Used by permission of the publisher Romand & Littlefield.