Abstract

In view of the current situation with a worldwide pandemic, the use of online teaching has become critical. This is difficult in the context of human anatomy, a subject contingent primarily on the use of human cadaveric tissues for learning through face-to-face practical laboratory sessions. Although anatomy has been taught using online resources including 3D models and anatomy applications, feedback from students and academic staff does not support the replacement of face-to-face teaching. At Charles Sturt University, we were obligated to cancel all classes on-campus in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We ran exclusive online anatomy practical classes replacing classes usually run on campus. We designed an alternative program that consisted of twenty pre-recorded videos that were prepared in the anatomy laboratory using cadaveric tissues, and then discussed in live (and interactive) tutorials. Furthermore, innovative approaches to learning were shown and encouraged by the lecturer. Student survey responses indicated a positive response to both the anatomical videos and the innovative learning approaches. The results obtained by students showed a statistically significant increase in high distinctions and marked decrease in the amount of fail grades, compared with the previous three years (not online). The use of these videos and the encouragement of innovative learning approaches was a novel experience that will add valuable experiences for improved practice in online anatomy teaching. We propose that online anatomy videos of cadavers combined with innovative approaches are an efficient and engaging approach to replace face-to-face anatomy teaching under the current contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although there is a growing interest in online teaching in higher education, this has been more challenging in the area of human anatomy that depends primarily on the use of face-to-face lectures and human cadaveric tissues for learning through face-to-face practical laboratory sessions. Learning anatomy via face-to-face use of cadaveric tissues has historically been an expectation, and indeed a rite of passage, for medical and health science students. Anatomy is a complex three-dimensional subject with a variety of inherent and contextual challenges [1, 2]. Anatomy is a demanding subject with new terminologies that students traditionally find dull and labour-intensive [3], and they tend to “memorize” lists of names in a typical “surface-learning” approach [4]. COVID-19 has led to social distancing and self-isolation that has made the teaching of face-to-face anatomy difficult. The current situation with a global pandemic has led to immediate challenges for anatomy teaching all over the world and the use of online teaching has become essential [5, 6]. COVID-19 has disrupted anatomy education in two ways: (1) the adoption of online teaching and (2) changes to body donation programs that have been suspended or reduced significantly, at the risk of receiving bodies infected with COVID-19 [7].

Early reports of online instruction, pre-COVID-19, suggested savings in time and cost and often out-performance of traditional face-to-face teaching [8]. Students exposed to computer-aided instruction were found to out-perform their classically trained peers [9]. Evidence suggested that the quality of the technology being utilised for online learning needs to supersede that of campus-based materials [10] and this was corroborated in the practice of developing online content for a blended anatomy course [11]. Online laboratories using computer models [12,13,14], adaptive learning [15,16,17], and videos [18] were reported,however, greater feedback and results were obtained using wet laboratory sessions using human cadaveric tissues [19]. Although students consider online anatomy resources valuable in learning anatomy [20], their value in replacing face-to-face campus teaching is not supported [21]. Clear advantages were reported with the use of online summative assessments pre-COVID-19 [22], Kahoot online activities [23], and in Australia with concept maps with automated grading and feedback [24]. During COVID-19, online assessment has been reported to be appreciated by staff and students in Saudi Arabia [5, 25], although the use of online anatomy practical examinations has been more problematic with the validity and practicality of online exam delivery in question [26].

Despite chronic disruption to curricula, the COVID-19 pandemic presented opportunities to universities for development of new resources and skills [26], offering prospects for academic collaboration, working from home, upskilling in new technologies, incorporation of blended learning, and development of alternative assessment methods. Time constraints, lack of exposure to cadaveric material, and changes to assessment were identified as weaknesses of online teaching during COVID-19 [26]. A study in China reported that although many students enjoyed online teaching, many were keen to return to face-to-face education [27]. Similarly, in India, most students missed traditional face-to-face anatomy learning and interactions and reported a lack of self-motivation [28]. In Italy, plastic surgery residency training during COVID-19 used Anatomage, an academic touch screen table in combination with the Touch Surgery application for smartphones and tablets as a useful aid during the pandemic [29]. In Australia and New Zealand, there was a loss of “hands-on” experiences for students, impact on workloads, and expansion into remote learning spaces [30]. Many anatomists expressed concern about lack of practical sessions/cadaveric exposure, reductions in student engagement, and diminished student–teacher relationships through the pandemic [26]. The ethical and legal constraints of sharing and displaying digital images of prosected human donor bodies/body parts increased the challenges to anatomy online education in Australia and New Zealand [30]. Innovative experiential approaches to learning anatomy that improve student engagement and learning outcomes have been reported until 2020 [31, 32].

The aim of this study was to implement a novel educational strategy for learning anatomy during COVID-19; anatomy was taught exclusively online using pre-recorded videos in the anatomy laboratory using cadaveric tissues combined with the use of innovative teaching approaches.

Methods

This study was conducted from July-November 2020, using students enrolled in the Head and Neck Anatomy subject at Charles Sturt University (CSU), Albury. There were a total of 123 distance students: 9 males with an average age of 29 and 114 females with an average age of 33. The majority of students indicated that they had never completed a science subject before and so were very anxious about completing an anatomy subject. The majority of students completed the Head and Neck Anatomy subject to be eligible to apply for the competitive Master of Speech Pathology online course at CSU. Before 2020, students would attend a Residential week on-campus where they would participate in face-to-face anatomy practical classes. With the onset of COVID-19, all residential classes were cancelled in August after the subject had commenced; the subject coordinator (lecturer) was informed that there would no longer be students attending campus, no anatomy practical classes, and no opportunity for students to do innovative learning in the laboratory. The subject coordinator had limited time to develop an alternative strategy to teach human anatomy, including practical classes, online.

There were no cut backs to anatomy staff at CSU due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The sole lecturer in charge of running this subject (CD) was an experienced anatomist with over 25 years’ experience teaching anatomy in Australia.

It was decided to use two novel approaches to replace face-to-face anatomy practical classes and teaching during 2020.

-

1.

All human anatomy was taught online using pre-recorded lectures uploaded on the Learning Management system (LMS) and weekly tutorials using Zoom. Practical anatomy classes were taught online using a series of 20 pre-recorded videos in the anatomy laboratory using cadaveric tissues. The video series was developed using a Sony HDR-CX625 and Sony PXW X70 video recorders and a Sony EMV AW4 wireless microphone. The video was recorded at 720P resolution. The video editing was completed using ACDSee Video Studio 4. Primary video footage was taken using the PXWX70, with a medium close-up camera framing. The secondary footage was taken using the CX625. The positioning of the camera was mounted above the presenter facing downward onto the bench using a close-up framing. The secondary footage was edited into video using a “picture in picture” function to allow the view to see the presenter as well as a detailed view of the specimen. Final videos were uploaded onto the LMS for the subject. Permission was granted by N.S.W. Health to produce these videos in line with the Human Anatomy Act 1977 for body donations in N.S.W. All videos were presented by the lecturer (CD) in a respectful manner. Students were instructed that reproduction of videos was prohibited by law. Tutorials using Zoom were run during evenings to allow students to discuss and ask questions regarding the material, including the videos. Furthermore, students were given a weekly practice online quiz on the LMS, a Kahoot quiz at the beginning of each tutorial class and a series of practice practical and theory questions at the end of each tutorial. Before each exam, students were also given practice viva (oral examination) questions to help them prepare for the examination. Students were provided ample resources for learning and examination preparation in this subject.

-

2.

The lecturer introduced and encouraged the use of “hands-on,” innovative learning approaches to increase the engagement and motivation for doing anatomy online: drawing and whiteboarding for visual learners, Play-doh for tactile learners, singing and dancing, body gestures for kinaesthetic learners, surface anatomy, body painting for visual, tactile, and kinaesthetic learners. This online subject was taught to students from all over Australia, and included one student in Antarctica. Many students were in lockdown situations and finding a way to engage them at this difficult time was paramount. The lecturer showed students examples of previous work by anatomy students and gave them instructions on how they could complete some of these approaches at home. For example, the process of body painting as a learning tool was explained to them in detail with focus on the process of body painting (observation, palpation, landmarking then finally painting) rather than the finished product. The concept of drawing and “whiteboarding” and the power of mind mapping were also elucidated. Furthermore, they were shown examples of the use of “Play-doh” to build anatomical structures and the use of hand and body gestures and movements for understanding anatomy. The lecturer actively used and encouraged gestures for gaining attention and improving learning. The Circle of Willis for example was taught by the lecturer using a pseudo-interpretive dance using the arms to show the position and course of the arteries to form the structure.

Assessments were run as two examinations, mid-way and at the end of the session. Each examination consisted of 50 randomized multiple-choice questions and 6 short answer questions consisting of diagrams to label and related questions within 90 min. Examinations were similar to the examinations in 2017–2019. Examinations were completed online by students at home using a timer. Online examinations were not invigilated; however, the focus from the online format was moved by introducing time constraints; the limited examination time did not appear to provide sufficient time for academic dishonesty. Furthermore, students also completed an online viva (oral examination) on Zoom with the lecturer (CD) following the written exam, thus addressing the issue of academic integrity. All examinations were moderated by an independent academic to ensure validity and fairness. All graphs were produced using GraphPad Prism (version 7.04). The final results for Head and Neck Anatomy were compared with results from this subject in 2017–2019. The raw data was analysed using a one-way ANOVA, with the distribution of grades expressed by way of box plot. The correlation between the viva (oral examination) and end of session examination was analysed with a Pearson correlation coefficient. All statistical analysis was completed using the statistical package GraphPad Prism with the significance level set at P < 0.05.

At the end of the teaching session, all students were invited to participate in this study by completion of an online survey; their participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous and did not influence their results. Human ethical approval was obtained from the CSU Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number H20320. This included approval for surveys and a waiver of consent for the use of retrospective data (marks) that was pooled and de-identified. Students were given a link to a SurveyMonkey survey that they could fill out. Additionally, we were able to examine the final results for the subject to observe student achievements and these were compared with results from the previous 3 years (the subject was run twice a year).

The SurveyMonkey surveys presented a series of questions as follows:

-

1.

What was the overall quality of your learning experiences from the anatomy videos?

-

2.

Do you think the anatomy videos were relevant to the topics being studied?

-

3.

Do you think the anatomy videos are relevant to your current and/or future study in your discipline?

-

4.

Did the anatomy videos help you in understanding the anatomy topics?

-

5.

Do you feel the anatomy videos assisted your deeper understanding of anatomy?

-

6.

Do you feel the anatomy videos assisted your long-term memory of anatomy?

-

7.

What was your overall level of enjoyment from watching the videos?

-

8.

Did you benefit/enjoy learning innovative learning approaches?

Results

Survey Results

Forty-two of 123 enrolled students (35%) completed an online survey, consistent with previous reports that average response rates for online surveys (33.3%) are lower than on-paper surveys [33]. Analysis of the 8 survey questions indicated that students overwhelmingly reported a substantial benefit from the anatomy videos and the innovative learning approaches in the subject. Overall, 89% of students reported a substantial learning experience from the videos (Fig. 1, Q1). All students reported that videos were relevant to the topic being studied and 86% of students reported the videos were relevant to their discipline (substantial score; Fig. 1, Q2 and 3). The videos and innovative approaches were reported to assist with understanding (91%), deep understanding (88%), and long-term memory of anatomy (Fig. 1, 83%, Q4, 5, and 6 respectively). The majority of students reported a substantial level of enjoyment from watching the videos (Fig. 1, 83%, Q7) and a substantial benefit from the innovative learning approaches used in the subject (Fig. 1, 94%, Q8).

A Correlation between the viva (oral examination) mark and final exam mark, expressed as a percentage. Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.8644, P < 0.0001. B The average grades for Head and Neck anatomy from 2017 to 2019 taught with an on campus residential school and taught exclusively online in 2020. Data is expressed as a percentage

Student Comments

Student comments obtained from the online surveys were very positive regarding both the anatomy videos and the innovative learning approaches (Table 1). Several comments appreciated the respectful way in which the videos were developed. Students reported that the lecturer’s enthusiasm was contagious, that the videos were a game changer, and that the innovative approaches used in this subject boosted confidence, were engaging, and enjoyable.

Assessment

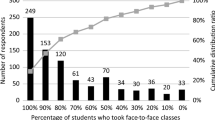

The final results for this subject (exam 1 + exam 2) reflected the success of the online anatomy learning that occurred this session (n = 123; Fig. 2). Student results improved significantly from exam 1 to exam 2 as they became more confident and as they developed their skills for deep and long-term learning. Interestingly, many students displayed their newly-learned skills during the oral viva’s (oral examination), using hand and body gestures to present their answers. The average mark for the oral viva was 88%, and they provided an opportunity to see what student’s had learnt with a very low risk of academic integrity. There was a significant correlation between the oral viva mark and the mark on the final exam (r = 0.8644, P < 0.0001). Over 78% of students obtained a distinction (75–84) or high distinction (85–100) as a final mark. Although the majority of final marks were high, there were still a few students who failed the subject suggesting that the standard of testing was not easy. This is further seen in Fig. 2B, where we see a histogram establishing a higher frequency of high distinctions in 2020, and less fail grades, compared to average grade distributions seen from 2017 to 2019. The proportion of students obtaining high distinctions increased markedly from an average of 32.2% between 2017 and 2019 (range 20–39%) to 54.8% in 2020 using online anatomy teaching during the pandemic. Notably, the proportion of students obtaining fails in the subject decreased significantly from an average of 22.6% during 2017–2019 to 1.6% in 2020 during the pandemic. Subject progress rates, calculated as the percentage of students receiving a passing grade remained stable from 2015 to 2019 at 84–85%. In 2020, the progress rate increased by 10 to 94%.

A comparison of the distribution of subject results from 2018 to 2020 is summarized in Fig. 3. As can be seen from the spread of grades from 2018 to 2020, when the novel online teaching techniques were established, a significant improvement in the overall grades for the cohort was seen (P < 0.05).

Innovative Learning

Students were open to instruction and demonstration of innovative approaches by the lecturer. They were very receptive to the innovative learning challenge and they produced very notable results. The lecturer was enthusiastic, passionate, and supportive when teaching anatomy, thus providing a stimulating and nurturing environment that made learning engaging, enjoyable, and inclusive for all students. Students shared their work (n = 67) on the subject web page regularly which was appreciated by all students and encouraged peer learning. Interestingly, the majority of work presented was prepared by the mature-age students. Several students also put their anatomy to song that was a creative and powerful learning tool that they shared with the class during online tutorials. Examples of student work included drawings (Fig. 4), use of Play-doh to build anatomical structures (Fig. 5) and origami, 3D printing, and body painting of children (Fig. 6). Students were encouraged to buy skulls for this subject, and they used Play-doh to learn the muscles of the face and neck (Fig. 5A) and pipe cleaners to learn the positions and course of cranial nerves (Fig. 6E). Students went out of their way to draw on screen doors, walls, furniture, and mirrors in their homes (Fig. 7A, B). During online tutorials via Zoom, students were always happy to share their work and use their hands, arms, and bodies to demonstrate anatomy in motion (Fig. 7C). The lecturer offered feedback and positive praise for all the creative and productive work produced by students.

Students took advantage of their own homes, drawing on pantry doors “Pantry Willis” for the Circle of Willis (A), walls, and mirrors. One student drew everything backwards so he could see it in the mirror when in the bathroom (B). The use of hands and bodies for learning was encouraged as can be seen here where a student remembered the position of the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle on the back of the larynx with the use of her hands (C). She taught this to the entire class who were seen to use this in their oral examinations

Discussion

Anatomy is a subject that is not commonly conducive to an online format. However, for this subject, we were able to implement a highly engaging, motivating, and efficient model for online anatomy learning. Our work differed from most previous reports in that we successfully taught anatomy exclusively online.

The advantages of using anatomy video recordings combined with the use of experiential learning through the innovative approaches were a high level of engagement and motivation and an improvement in final results compared with previous years. An increase in the proportion of students obtaining high distinctions demonstrated the success of the online delivery of anatomy at CSU during 2020. More notably, a significant decrease in the proportion of students failing the subject was an indication of the efforts of the lecturer to engage students and to assist students to learn effectively. This resulted in an increase in the subject progress rate and student grades. In response to COVID-19, all examinations were moved into an online format in 2020 and the head and neck examination was not invigilated. It could be argued that students’ grades were inflated in 2020 due to this fact; however, the authors feel that the increased engagement that was observed during the subject was reflected in the higher quality of assessment and not because the exam was moved online. To ensure the academic integrity of the subject, the viva (oral examination) was introduced as an assessment item. Students were asked 10 questions for which they provided a verbal reply over Zoom to both the lecturer/marker and a second academic acting as a moderator. There was a very high, significant, correlation between the invigilated viva (oral examination) and the non-invigilated final exam. Furthermore, the final exam was time limited, reducing the opportunity for academic misconduct. Analysis from 24 subjects in the same University Faculty found no difference in exam marks or cumulative marks between 2019 and 2020 with Zoom invigilation [34]. There appears to have been a clear shift in marks upwards that was most apparent at either end of the scale. Using the innovative approaches, students tended to achieve higher marks through increased motivation and effort, therefore resulting in fewer fails. In fact, it appeared that lower performing students benefited most from the subject improvements. This is particularly advantageous in subjects that have high fail rates. One student in particular went from a fail mark of 48% in the first exam to a mark of 89% in the final exam, pushing their grade up from a fail to a high credit. This student asked the chief investigator for assistance and attended several zoom sessions to improve their learning approaches; there was a clear improvement in motivation and effort. This appeared to happen to many students who were able to obtain higher grades than expected. The use of innovative approaches has been shown previously to increase student engagement, learning and results [31, 32]. At CSU in 2020, students displayed a clear improvement from the first to the final exam, suggesting an improvement in their “learning skills” and development of their deep learning. The use of online videos, though time-consuming initially, was a valuable and good replacement for face-to-face anatomy practical classes. The anatomy videos allowed consolidation of knowledge and learning of the topics using cadaveric tissues.

Furthermore, the encouragement of innovative learning together with the anatomy videos offered a novel alternative to face-to-face teaching. It has been reported that an engaging and supportive teacher assists student learning through positive peer interactions and interest in the subject [35]. The student work produced demonstrated enthusiasm and engagement and self-isolation and lockdown appeared to encourage greater creativity among students. Students had a lot more time to dedicate to their studies, and they produced many valuable and educational pieces of work that were shared amongst the cohort, thus encouraging peer interactions. Peer interactions are important in developing social skills for collaborative learning which increases motivation for students to learn. “Engagement Theory” proposes that students need to be engaged in meaningful learning activities involving peer interaction to achieve deep learning [35,36,37]. The encouragement of gestures by the lecturer was another innovative approach to improve student learning in this subject. The use of gestures by the lecturer in this subject had a trickle-down effect on the students, and they used these regularly in the tutorials and in the viva (oral examination). It has been reported that that the use of gestures can change cognition and improve understanding [38]. Moreover, gestures have the power not only to reflect a learner’s understanding, but also to change their understanding. Teachers’ gestures can guide student’s attention and lead to increased student gesturing that improve learning and understanding [39]. The innovative learning approaches were very engaging and motivating and appeared to lead to deep and life-long learning. Students demonstrated clear development of self-directed learning skills during the subject. Most importantly, the innovative approaches were a lot of fun for students and they led to good learning outcomes and grades. Most of the students who scored distinctions and high distinctions were the same students that shared their creative, innovative work with the class. The mature-age students doing this course (30–50 years old) tended to be the ones most engaged with the innovative approaches and many explained how they enjoyed learning in such a different way “The lecturer encouraged us to try new ways of learning and I found myself painting my children’s faces and making plasticine models to consolidate my learning – processes I had never thought about using when I had previously studied.”

We did not appear to have major issues regarding connectivity. Tutorials and assessments were scheduled to ensure that all students were able to attend, despite their geographical location (Western Australia, Antarctica). Students had access to many anatomy applications on their computers and mobile phones, and while these were valuable, the major engagement occurred through the anatomical videos and innovative learning approaches used in this subject at CSU during COVID-19.

As we cope with this pandemic, being able to compromise, and adapt in practice and curriculum design and teaching delivery, is important. Changes to curriculum normally take years to research, enforce, and evaluate. However, the current crisis has forced academics to make radical adjustments in a short period of time. This was a global issue that impacted the higher education landscape and indeed was the situation at CSU during 2020. The lecturer was able to come up with a suitable alternative to face-to-face learning within a few weeks. The use of these videos combined with innovative learning approaches was a novel, engaging, valuable and efficient experience that will add valuable experiences for improved practice in anatomy teaching. We propose that online anatomy videos of cadavers combined with innovative approaches are an efficient and engaging approach to replace face-to-face anatomy teaching under the current circumstances. Almost all anatomists believe that anatomy education is likely to change permanently given the scale of change during the pandemic, with some concerned that this change will call into question traditional laboratory-based approaches, in favour of modern (now trialled) online and remote learning approaches. This was our experience at CSU during 2020. This work will provide experimentation with new online teaching techniques and reshape learning and teaching spaces to build new experiences for students and staff.

Moving forward with online anatomy teaching and learning, assessments remain the most complicated and yet to be determined component of Australian and New Zealand anatomy education. Online assessments introduce new challenges for integrity and fairness of results, and much work will need to be done to improve and optimize assessment processes for online anatomy subjects. Students have been reported to prefer online examinations compared to paper exams, due to greater flexibility and faster access [40,41,42]. It has been reported that student performance does not differ significantly across online and traditional examination modes [43,44,45]. It has been reported previously that a strict assessment time limit played an important role in maintaining academic integrity [46]. Our experience running online examinations was good. Students appeared to show integrity in completing examinations and we believe that the limited time for examinations made cheating difficult, which was confirmed by including the viva (oral examination) assessment.

Conclusion

We have managed to implement an engaging and successful transition to teaching human anatomy exclusively online at CSU. The combination of anatomy videos recorded in the laboratory using cadaveric tissues with innovative teaching approaches provided a powerful, non-didactic approach that encouraged self-directed learning, deep and life-long learning. Students were shown “how to learn anatomy” using experiential approaches that promoted high engagement and a shift in attitudes towards learning. This study supports the report that the role of an anatomy teacher is not to teach students anatomical facts, but rather to teach them the learning skills that will serve them throughout their student and professional lives [32]. Online anatomy delivery during the pandemic resulted in surprising creativity that encouraged peer learning and benefited the whole student cohort and resulted in high final results for students. Subjects like this one at CSU will offer community engagement by offering alternatives for minorities and integration between secondary and tertiary education. Due to the success of the online delivery of Head and Neck Anatomy in 2020 during COVID-19, this subject will run as an exclusive online subject from 2021 onwards.

References

Estai M, Bunt S. Best teaching practices in anatomy education: a critical review. Ann Anat - Anatom Anz. 2016;208:151–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2016.02.010.

Patel K, Moxham B. Attitudes of professional anatomists to curricular change. Clin Anat. 2006;19(2):132–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.20249.

Biggs J. Constructing learning by aligning teaching: constructive alignment. Teaching for quality learning at university: what the student does. 2nd ed. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press; 2003.

Trigwell K, Proser M, Waterhouse F. Relations between teachers’ approaches to teaching and students’ approaches to Learning’. High Educ. 1999;37:57–70.

Alkhowailed MS, Rasheed Z, Shariq A, Elzainy A, El Sadik A, Alkhamiss A, Alsolai AM, Alduraibi SK, Alduraibi A, Alamro A, Alhomaidan HT, Abdulmonem WA. Digitalization plan in medical education during COVID-19 lockdown. Inform Med Unlocked. 2020;20:100432.

Brassett C, Cosker T, Davies DC, Dockery P, Gillingwater TH, Lee TC, Milz S, Parson SH, Quondamatteo F, Wilkinson T. COVID-19 and anatomy: stimulus and initial response. J Anat. 2020;237(3):393–403.

Lemos GA, Araujo DN, de Lima FJC, Bispo RFM. Human anatomy education and management of anatomic specimens during and after COVID-19 pandemic: Ethical, legal and biosafety aspects. Ann Anat. 2021;233:151608.

Chen NS, Ko HC, Kinshuk LT. A model for synchronous learning using the Internet. Innovat Educ Teach Int. 2005;42:181–94.

Wilson AB, Brown KMB, Misch J, Miller CH, Klein BA, Taylor MA, Goodwin M, Boyle EK, Hoppe C, Lazarus MD. Breaking with tradition: a scoping meta-analysis analyzing the effects of student-centered learning and computer-aided instruction on student performance in anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;12:61–73.

Kimball L. Managing distance learning: new challenges for faculty. In: Hazemi R., Hailes S. (eds) The Digital University—building a learning community. Computer Supported Cooperative Work. London: Springer; 2002. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-0167-3_3.

Green RA, Whitburn LY. Impact of introduction of blended learning in gross anatomy on student outcomes. Anat Sci Educ. 2016;9:422–30.

Attardi SM, Rogers KA. Design and implementation of san online systemic human anatomy course with laboratory. Anat Sci Educ. 2015;8(1):53–62.

Attardi SM, Barbeau ML, Rogers KA. Improving Online Interactions: lessons from an Online Anatomy Course with a Laboratory for Undergraduate Students. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(6):592–604.

Erolin C. Interactive 3D digital models for anatomy and medical education. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1138:1–16.

Linden K, Pemberton L, Webster L. Preparing for anatomy assessment with adaptive learning resources: it is going “tibia” okay!. Proceedings of the 5th Int Conf on High Educ Adv: HEAd'19 2019a:633–640. Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València.

Linden K, Pemberton L, Webster L. Evaluating the bones of adaptive learning: do the initial promises really increase student engagement and flexible learning within first year anatomy subjects? Proceedings of the 5th Int Conf on High Educ Adv: HEAd'19 2019b:331–339. Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València.

Muhammed, Yakin K, Linden. Adaptive e‐learning platforms can improve student performance and engagement in dental education. J Dent Educ 2021;85(7):1309–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12609

Langfield T, Colthorpe K, Ainscough L. Online instructional anatomy videos: student usage, self-efficacy, and performance in upper limb regional anatomy assessment. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(5):461–70.

Mathiowetz V, Yu C-H, Quake-Rapp C. Comparison of a gross anatomy laboratory to online anatomy software for teaching anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2016;9(1):52–9.

Green RA, Whitburn LY, Zacharias A, Byrne G, Hughes DL. Anat. Sci Educ. 2018;11(5):471–7.

Swinnerton BJ, Morris NP, Hotchkiss S, Pickering JD. The integration of an anatomy massive open online course (MOOC) into a medical anatomy curriculum. Anat Sci Educ. 2017;10(1):53–67.

Inuwa IM, Taranikanti V, Al-Rawahy M, Habbal O. Anatomy practical examinations: How does student performance on computerized evaluation compare with the traditional format? Anat Sci Educ. 2012;5:27–32.

Felszeghy S, Pasonen-Seppänen S, Koskela A, Nieminen P, Härkönen K, Paldanius KMA, Gabbouj S, Ketola K, Hiltunen M, Lundin M, Haapaniemi T, Sointu E, Bauman EB, Gilbert GE, Morton D, Mahonen A. Using online game-based platforms to improve student performance and engagement in histology teaching. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:273.

Ho VW, Meng M, Hwang GJ, Pather N, Kumar RK, Vickery RM, Velan GM. Knowledge maps: An online tool for knowledge mapping with automated feedback. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29:625–9.

Elzainy A, El Sadik A, Al AW. Experience of e-learning and online assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic at the College of Medicine, Qassim University. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2020;15(6):456–62.

Longhurst GJ, Stone DM, Dulohery K, Scully D, Campbell T, Smith CF. Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, Threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13(3):301–11.

Cheng X, Chan LK, Pan S-Q, Hongmei C, Li Y-Q, Yang X. Gross anatomy education in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Anat Sci Educ. 2021;14(1):8–18.

Singal A, Bansal A, Chaudhary P, Singh H, Patra A. Anatomy education of medical and dental students during COVID-19 pandemic: a reality check. Surg Radiol Anat. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-020-02615-3.

Zingaretti N, Contessi Negrini F, Tel A, Tresoldi MM, Bresadola V, Parodi PC. The impact of COVID-19 on plastic surgery residency training. Aesthetic plas surg. 2020;26:1–5.

Pather N, Blyth P, Chapman JA, Dayal MR, Flack NAMS, Fogg QA, Green RA, Hulme AK, Johnsdon IP, Meyer AJ, Morley JW, Shortland PJ, Strkalj G, Strkalj M, Valter K, Webb AL, Woodley SJ, Lazarus MD. Forced disruption of anatomy education in Australia and New Zealand: An Acute Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13(3):284–300.

Diaz CM. Chapter 12. Innovation in anatomy teaching. In: . Editor Paul Ganguly. Education in anatomical sciences. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2013. pp. 155–173.

Diaz CM, Woolley T. Engaging multidisciplinary first year students to learn anatomy via stimulating teaching and active, experiential learning approaches. Med Sci Educ. 2015;25(4):367–76.

Nulty DD. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess Eval High Educ. 2008;33(3):301–14.

Linden K, Gonzalez P. Zoom invigilated exams: a protocol for rapid adoption to remote examinations. Br J Educ Tech. 2021;00:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13109.

Kift S. Articulating a transition pedagogy to scaffold and to enhance the first year student learning experience in Australian higher education. Final Report for ALTC Senior Fellowship Program. 2009.

Kearsley G, Schneiderman B. Engagement theory: a framework for technology-based teaching and learning. Educ Technol. 1998;38(5):20–3.

Kuh GD. High impact activities and implications for curriculum design. Queensland University July. 2009.

Goldin-Meadow S, Wagner AM. Gesture’s role in speaking, learning, and creating language. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:257–83.

Novack M, Goldin-Meadow S. Learning from gesture: how our hands change our minds. Educ Psychol Rev. 2015;27(3):405–12.

Attia M. Postgraduate students’ perceptions toward online assessment: yhe case of the faculty of education, Umm Al-Qura University. In: Wiseman A, Alromi N, Alshumrani S, editors. Education for a knowledge society in Arabian Gulf countries. United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; Bingley; 2014. p. 151–73.

Böhmer C, Feldmann N, Ibsen M. E-exams in engineering education—online testing of engineering competencies: experiences and lessons learned. IEEE global engineering education conference (EDUCON) 2018 (pp. 571–576).

Williams JB, Wong A. The efficacy of final examinations: a comparative study of closed-book, invigilated exams and open-book, open-web exams. Br J Educ Tech. 2009;40(2):227–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00929.x.

Gold SS, Mozes-Carmel A. A comparison of online vs. proctored final exams in online classes. J Educ Tech. 2009;6(1):76–81. https://doi.org/10.26634/jet.6.1.212.

Oz H, Ozturan T. Computer-based and paper-based testing: does the test administration mode influence the reliability and validity of achievement tests? J Lang Ling Stud. 2018;14(1):67.

Stowell JR, Bennett D. Effects of online testing on student exam performance and test anxiety. J Educ Comp Res. 2010;42(2):161–71. https://doi.org/10.2190/ec.42.2.b.

Ng CKC. Evaluation of academic integrity of online open book assessments implemented in an undergraduate medical radiation science course during COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2020;51(4):610–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr Matthew Gill and Ms Emily flint for their technical assistance in preparation of the anatomy videos.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number H20320.

Informed Consent

Implied consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study by completion of the survey.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Practice Points

• Online anatomy videos can effectively replace face-to-face anatomy practical classes.

• Online anatomy teaching requires engagement through innovative approaches.

• Online teaching can show students “how to learn anatomy” using experiential approaches.

• Online anatomy teaching can be fun and achieve outstanding results.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diaz, C.M., Linden, K. & Solyali, V. Novel and Innovative Approaches to Teaching Human Anatomy Classes in an Online Environment During a Pandemic. Med.Sci.Educ. 31, 1703–1713 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01363-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01363-2