Abstract

Many parents experience grief and loss in response to their child receiving an autism diagnosis in early childhood. However, there is a dearth of research that considers if grief and loss are experienced by parents throughout their child’s adolescence and young adulthood. Further, there is a small but growing body of evidence suggesting that parents of autistic children may be living with ambiguous loss in particular, that is, a loss for which there is no closure or resolution. This case study introduces a peer group intervention utilizing an ambiguous loss framework that school social workers and other clinicians can adopt to support mothers of autistic adolescents who are struggling with ambiguous loss. Through the group process, the mothers developed deeper understanding, self-compassion, and effective coping strategies, resulting in a more resilient approach to the transition process and an enhanced capacity to plan for a meaningful adult life with their autistic child.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One out of every 54 children in the United States received an autism diagnosis in 2016, a rate that has been steadily increasing over the past two decades (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), autism spectrum disorder is a developmental disability characterized by persistent functional limitations in social-emotional, relational, and communication domains. To receive a diagnosis of autism, one must also exhibit “restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities” (pg. 50). There is, of course, a unique child behind each of these diagnoses; so, too, is there a family.

Children with developmental disabilities often bring much joy and meaning to a family’s life (Hastings et al., 2005). However, many parents also experience grief and loss in response to the diagnosis (Brown, 2013). The question of grief and loss in parents of autistic children is not without controversy. Historically, professionals and families have often considered a diagnosis of autism to be devastating news. In recent years, however, the neurodiversity movement has been actively challenging this notion (Cascio, 2012). Advocates of the neurodiversity movement consider autism a neutral or even positive neurological variation in humanity. Thus, many autistic individuals feel that it is offensive and hurtful for others, particularly one’s own family, to grieve the diagnosis (Sinclair, 2012). Nevertheless, a rich body of literature demonstrates that for parents, grief and loss occurs, particularly at the time of diagnosis and through early childhood (Brown, 2013; Bruce & Shultz, 2002; Krishnan et al., 2017). Despite the evidence that family milestones, such as those that occur when a child graduates from high school, often trigger feelings of loss in parents (Brown, 2013; Lustig & Thomas, 1997), there is a dearth of literature exploring if and how parental grief and loss affects the family unit during the adolescent years.

Pauline Boss (1999, 2006, 2007, 2016) defines a loss wherein the loved one remains physically present but not psychologically or emotionally available as an “ambiguous loss.” Due to the social-emotional and relational challenges experienced by those with autism, interventions born from ambiguous loss theory may be effective in supporting parents of autistic children (Ho et al., 2018; O’Brien, 2007). While the benefits of support groups for parents of children with disabilities have been well documented (Hartley & Shultz, 2015; Jackson et al., 2018), there is currently no literature that explores the use of ambiguous loss as a relevant theoretical framework with which to inform the implementation of an effective support group. The objective of this paper, then, is to review the literature regarding the presence of ambiguous loss in parents of autistic children, the challenges of the adolescent years and the transition to adulthood, and the ways a support group utilizing ambiguous loss theory can increase parental resilience. This case study will assert that by allowing space for parental grief to be shared and processed, parents can explore their emotions with one another rather than project unresolved grief onto their child, resulting in better outcomes for the entire family unit.

Historically, person-first language, as in, “woman with autism” has been considered the most respectful way to refer to a person who has received an autism diagnosis (American Psychological Association, 2021; Shakes & Cashin, 2019). However, in recent years, many autistic individuals have called this language into question, pointing out that autism is an integral part of who they are, as key to their identity as race, religion, ethnicity, and gender (Robinson, 2019). Consequently, there has been a widespread call for the use of identity-first language, as in, “autistic woman” (Robinson, 2019; Shakes & Cashin, 2019). While current APA guidelines dictate that either person-first or identity-first language are permissible (2021), in recognition of the preference of many autistic individuals, I will be using identity-first language throughout the remainder of this paper.

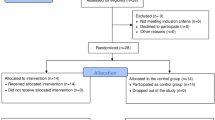

Methodology

The case study model is widely considered to be a useful qualitative approach to explore a theory by taking an in-depth look at a phenomenon in its real-life context (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Crowe et al., 2011). While a limitation of the case study is the inability to generalize the information broadly, it is nevertheless an effective tool to illustrate a unique clinical situation and novel strategy, and has the potential to inform further research and practice (Baxter & Jack, 2008; Crowe et al., 2011). The following case study describes a support group of eight mothers of autistic adolescents from the perspective of “Josie,” a composite of multiple group members. To further ensure confidentiality, all identifying information has been changed. The quotations provided in the case narrative are also a composite; this section was composed by reviewing personal case notes and compiling stories, comments, and experiences from several different individuals to form a cohesive singular narrative. As the literature review will reveal, the scholarly research has explored different aspects of the lives of parents of autistic children, including the presence of ambiguous loss, the challenges of transition planning, and the benefits of support groups. However, no literature explores how these topics intersect. This case study will demonstrate how maternal grief and loss is reawakened during the transition years, the impact it can have on maternal well-being and the transition process, and why ambiguous loss theory is an effective theoretical framework for the creation of a support group for mothers of autistic adolescents.

Literature Review

Ambiguous Loss

Pauline Boss (1999, 2006, 2007, 2016) describes two different kinds of ambiguous loss: physical ambiguous loss, wherein families do not know if a loved one is dead or alive, such as a soldier missing in action; and psychological loss, wherein the loved one is physically present, but not psychologically or emotionally available, as when families “lose” a family member, so to speak, to the dementia of Alzheimer’s disease (Boss, 1999). Those living with an ambiguous loss experience high levels of anxiety and frequently vacillate between having their hopes raised for their loved one to return (physically or psychologically) and the despair that comes when they do not (Boss, 2016). They also experience ambivalence, or conflicting emotions and thoughts, including both love and hate for their loved one, fulfillment and resentment about their role as caregiver, and acceptance and denial about the loss (Boss, 1999). As there are no rituals or ceremonies that bear witness to an ambiguous loss, one may feel isolated and unsupported by others, unable to find hope and meaning (Boss, 1999). Prior to Boss’s development of ambiguous loss theory, individuals experiencing an ambiguous loss were often diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and offered treatment accordingly. However, Boss observed that PTSD treatment was not helpful or appropriate because with ambiguous loss the person is not traumatized by a past event but grieves an ongoing and pervasive situation (Boss, 1999, 2016).

Parental Grief, Autism, and Ambiguous Loss

In one of the seminal articles on the topic of parental grief and loss, Moses (1987) posits that expectant parents often formulate hopes and dreams for their child. He argues that these are not just expectations but “…dreams that are key to the meaning of their existence, to their sense of being” (pg. 2). When a child is diagnosed with a developmental disability, those core dreams may be shattered. Parents may yearn not just for the typically developing child that they dreamed of but also for the parenting experience that they imagined for their own lives (Brown, 2013).

O’Brien (2007) was the first to consider that mothers of autistic children may be experiencing ambiguous loss. She conducted a two-part study with a sample of 63 mothers to explore if, when interviewed about their parenting experiences, the mothers would spontaneously use language to suggest an experience of ambiguous loss. They did, expressing ambivalence, loss of mastery, self-blame, and anxiety. She further hypothesized that maternal stress increased when mothers struggled to know where their own identity ended and that of their child began. To test her hypothesis, she utilized two combined subscales, one of which assessed a mother’s “preoccupation” with her child’s autism, and the other the mother’s belief in her ability to control her child’s outcomes. Next, she assessed the mothers’ depressive symptoms and confirmed that the prevalence of identity ambiguity contributed to maternal stress and depression (O’Brien, 2007).

Other researchers have affirmed O’Brien’s findings. Both Çelik and Ekşi (2018) and Bravo-Benítez et al. (2019) explored if parental grief and loss in families of autistic children can be considered an ambiguous loss. In both studies, parents frequently characterized their grief as a lack of connection with their child who they experience as emotionally unavailable (Bravo-Benítez et al., 2019; Çelik & Ekşi, 2018). These key findings describe a psychological ambiguous loss as defined by Pauline Boss (1999, 2007, 2016).

Support Groups for Mothers of Adolescents with Autism

Boss (2006, 2007, 2017) has stressed the ability of supportive peer groups to positively influence therapeutic outcomes for those living with an ambiguous loss. Within a group setting, parents often find comfort in having their experiences and emotions validated by other parents of autistic children and experience a heightened sense of agency when providing useful strategies to others (Bruce & Shultz, 2002). In addition, parents of autistic adolescents often experience elevated stress and anxiety due to the specific pressures of transition planning and may need additional opportunities to connect with social support networks during this time (White & Hastings, 2004).

In two-parent, heterosexual families, mothers have greater parenting responsibilities and are more likely to have left the workforce to provide care for their autistic child than fathers (Sharabi & Marom-Golan, 2018). In addition, mothers of autistic children experience higher levels of psychological distress including stress, anxiety, and depression than do fathers, parents of children without disabilities, and parents of children who have disabilities other than autism (Boyd, 2002; Bromley et al., 2004; Foody et al., 2015; Sharabi & Marom-Golan, 2018). To manage stress, mothers prefer supports that include a break from caregiving and provide opportunities to connect with others. Additionally, mothers are more likely than fathers to participate in support groups (Hartley & Shultz, 2015; Pelchat et al., 2003).

Ambiguous Loss, Autism, and Adolescence

While most adolescents experience some trepidation about entering adult life, autistic teenagers manage additional stressors related to their diagnosis. In addition to the perpetual challenge of navigating a neurotypical world, they may also have stressors related to their cognitive abilities, social and relationship skills, language and communication deficits, and emotional regulation (Roux et al., 2015; Timmons et al., 2004). According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004 (2017), transition services must “facilitate the child’s movement from school to post-school activities, including postsecondary education, vocational education, integrated employment…independent living, or community participation” (para. 1). Nevertheless, over 60% of autistic young adults are unable to secure meaningful roles in their community, such as post-secondary education or employment, in the immediate two years following graduation (Roux et al., 2015). For autistic individuals, this disconnection results in social isolation, regression of academic skills, increased difficulty securing and maintaining employment, and an increase of mental health challenges (Roux et al., 2015).

For parents, the transition years are no less daunting. They must grapple with difficult questions regarding their child’s social-sexual development, supports for educational and employment opportunities (Ankeny et al., 2009), long-term residential options (Scorgie & Wilgosh, 2011), and daily supports (Ho et al., 2018). Parents also must consider who will assume caretaking responsibilities for their child when they are no longer able to do so (Ankeny et al., 2009). Further, some parents experience a recurrence of grief when a child with a disability does not reach an expected developmental milestone (Brown, 2013; Bruce & Shultz, 2002). While social comparison is not unique to the transition years (Scorgie & Wilgosh, 2011), the milestones of young adulthood often carry additional emotional weight and parental yearning. For example, while parents of children without autism discuss their children going to college, getting engaged, or their own preparations for an empty nest (Scorgie & Wilgosh, 2011), some parents of autistic adolescents are again reminded of “what might have been” (Brown, 2013, pg. 117).

When planning for graduation, parents brace themselves for the reality that the educational supports and services upon which they have relied for many years will cease to exist after graduation day (Cheak‐Zamora et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2018). What lies ahead is a series of complex, underfunded, and often inadequate services that frequently fail to deliver the supports that an individual with a disability and their family needs to thrive (Ferguson & Ferguson, 1993; Scorgie & Wilgosh, 2011). Instead of relishing in the accomplishments represented by graduation, many parents lie awake wondering what will happen the morning after the school bus brings their child home for the last time.

Therapeutic Goals for Treating Ambiguous Loss

Pauline Boss (2006, 2017) recommends six non-linear therapeutic goals as a framework for clinicians to use with clients living with ambiguous loss. She states that one must find meaning in, or make sense of, what has been lost. To that end, she recommends that clinicians name and explain ambiguous loss, and when possible, facilitate group discussions among those who have experienced the same or a similar loss. She further suggests that many clients will need to modify their expectation for control, influence, and certainty, a concept she refers to as adjusting mastery. Specifically, some clients may need to temper their efforts to find certainty when none can be found; others may need the clinician to highlight when they can take steps to positively influence the situation. Boss describes the process of redefining oneself after an ambiguous loss as reconstructing identity. She argues that those living with ambiguous loss may no longer feel accepted in the same communities as they did before the loss. As human connection is crucial to resilience, she recommends clients find new spaces where they experience a sense of belonging.

Boss emphasizes the need for clients to understand that experiencing two opposing thoughts and emotions at the same time, or ambivalence, is a normal response to ambiguous loss. Consequently, she stresses that clinicians need to normalize ambivalence so that clients do not interpret it as a personal failure or inability to cope. She further argues that many clients will need to revise attachment to their loved one. Some parents of autistic children may still feel an attachment to a vision of their child or their parenting experience that is not reflective of their lived reality. The goal, then, is to balance that yearning with the recognition and appreciation of the gifts that the existing child, their relationship, and their lived experience as a parent has to offer. Finally, she stresses the importance of discovering new hope. Individuals experiencing ambiguous loss will increase resiliency by releasing old hopes that no longer apply to their lives and developing new hopes for the future.

Case Study

Group Formation

The support group described in this case study took place at a private high school for students with disabilities where I worked as both a social worker and the supervisor of the school’s transition team. In my decade long tenure in this capacity, I observed that for some parents, the stress and anxiety of the transition process would become unmanageable, and as a result, some would disengage from planning entirely. In such cases, not only were the parents in distress, but the lack of an appropriate transition plan put their children at risk of disengagement from community life. After consulting the literature, I began to recognize threads of ambiguous loss woven into the stories and struggles that these parents had shared with me. Drawing from the research on the efficacy of support groups for parents of autistic children and for those living with ambiguous loss, I concluded that a support group would likely be a helpful intervention.

While all school parents of children with an autism diagnosis between the ages of 18–21were notified of the formation of a support group, only mothers opted to attend. This is consistent with research, outlined previously, documenting the differences in preferred interventions between mothers and fathers of autistic children. The mothers were from a broad range of racial and socio-economic backgrounds, and like many with autism, their children struggled to make their way in a neurotypical world. They required assistance to make and maintain meaningful social connections and had significant deficits in adaptive skills such as self-care, community safety, and daily living. All would likely need considerable supports throughout their lives.

When I first met Josie, she was in her mid-50s. Josie, her husband, and her 20-year-old son Oliver lived together in a middle-class neighborhood in a large east coast city. As an observant Jewish family, they had strong ties to their local synagogue. Josie was a stay-at-home mother, having left the workforce when Oliver was 3 years old to focus on his needs and facilitate his busy therapeutic schedule. Known for her talkative nature and contagious laugh, Josie was an active participant in the school community.

One fall morning, I received a voicemail from Josie, inquiring about a specific adult service agency that she was considering for Oliver after graduation. As her family was on my caseload for transition planning, we were frequently in contact regarding such matters and there was nothing initially unusual about her inquiry. What happened then was unexpected. “Hi! So glad you called,” she said. “I need the number of the state commissioner for disability services because I don’t think any of these programs are going to be able to support Oliver. I think I should take this right to the top.” I paused. Few would argue that Josie’s advocacy in this context would be unwarranted. Many families and disabled individuals alike find the adult service system insufficient, confusing, and unreliable. And while I had no doubt that Josie would be an excellent ally for any advocacy efforts, I suspected that this moment was not about long-term planning for Oliver, but rather, was an attempt to alleviate her own immediate anxiety. I was concerned that her inability to quickly influence the broader landscape for disabled adults would ultimately make her feel less capable of handling Oliver’s more immediate affairs. “Before we get into all that,” I began, “I want to acknowledge that this is Oliver’s last year of school. And we know this is hard for Oliver, but this is hard for you, too.” I heard Josie take a deep breath. “Oh my god,” she began, “You have no idea. I’m just terrified.” Before concluding our conversation, I reminded her of the information I recently sent home regarding parent support groups and suggested she might consider joining. She immediately agreed to attend.

Engagement Phase

As a primary goal for those living with ambiguous loss is increased resilience (Boss, 2006), I began the first session by pointing out that collectively, there were 160 years of experience parenting autistic children in the room. I explained that my role would be to facilitate the group, but that ultimately the best support would come from the true experts—one another. After introductions and a few light ice breakers, I concluded the session by asking each mother to share one word describing how they were feeling about their child’s transition to adulthood. They said: “Terrified.” “Immobilized.” “Overwhelmed.” “Guilty.” Josie replied, “Hopeless.”

Recognizing that we cannot cope with ambiguous loss if we do not understand it (Boss, 2006), in the following session I familiarized the group with the theory by providing an overview of the main themes and how they may manifest in their lives. I stressed that not all mothers of autistic children experience loss, but for those that do, heightened emotions tend to be triggered by major life milestones. I acknowledged that adolescence was full of such milestones and that it was a common time for parents to struggle. Josie shared that she had, in fact, been struggling more recently, and while she was relieved to hear it was normal, she was nevertheless frustrated with her personal lack of closure regarding Oliver’s diagnosis. She explained, “Just when we get our footing, something changes with him, and we’re recalibrating again. I never know what he’s going to need from one month or year to the next. It never feels resolved.” I explained to Josie and the group that their difficulty finding closure was not because of a personal failure, but because, despite popular belief to the contrary, closure simply does not exist (Boss, 2006). Instead, the objective was to live well coexisting with the loss. What’s more, these mothers were searching for their footing while navigating an unreliable service delivery system and trying to envision meaningful adult lives for their children in a world that is often not accepting or accommodating of autistic individuals. I added, “This is so hard, because you’re all trying to plan for the future on such unsteady ground. This is not easy.”

Middle Phase

Those who live with ambiguous loss benefit from the realization that ambivalence is a normal response to their circumstances (Boss, 2006). Many assume that clarity of mind and heart will foster a sense of easement and will therefore seek to simplify their feelings into one “right answer.” In fact, doing so often contributes to suffering. For example, I shared that it was common for mothers to experience both meaning and resentment in their role as their child’s primary caretaker. Further, many parents had told me that because of their child, they have learned how to be a better, more present, and more compassionate person. And yet, those same parents also shared that on their hardest days, they wish autism was not such a prominent part of their lives. I noticed Josie had a hand on her heart and a thoughtful expression on her face, and I checked in to see how she was feeling. She confessed that throughout Oliver’s life she had plenty of those kinds of thoughts, but they generally caused a great deal of shame, and as a result, she did not let them linger. I asked her, “What if you gave yourself permission to feel it all? What would that be like for you?” Josie indicated that the idea scared her somewhat, as if experiencing her full range of emotions would be more than she could handle. But she also described the experience of having her complex emotions normalized as “an unexpected comfort.” I emphasized to the group that these kinds of ambivalent thoughts are a normal response to ambiguous loss; they are not in response to their children whom they unconditionally love and accept, and learning to see the difference will take some time and self-compassion. I added, “The truth is we need to let all our feelings have a seat at the table. Otherwise that ‘stuffed down’ emotion will pull up a chair anyway, even if it’s not invited, and be a lot more disruptive.” Josie, a bit under her breath, joked, “Wow, that sounds like my mother-in-law.” The entire group erupted into much-needed laughter.

Throughout the year, Josie needed ongoing support to adjust her sense of mastery. For example, she frequently shared her exhaustion at the magnitude of Oliver’s personal care needs and her corresponding responsibilities. So, the group was surprised when, one day in February, Josie pulled the admissions criteria for a prestigious university out of her purse and slammed it on the table. She angrily accused the school of failing to prepare students for a competitive college experience, suggesting the faculty was not up to the task. I noticed a defensiveness within me and I had to resist the urge to defend myself and my colleagues. Rather than push back against her assertion that her son was being failed academically, I asked her what it would mean to her if Oliver could attend such a respected university. She initially responded with irritation, saying that it is widely recognized that a university experience results in higher earning potential and elite networking opportunities. Then with a softened tone, she mentioned she had met her husband at college. “I mean, if he doesn’t get married, then who is going to make him dinner or help him shower when I’m not here anymore?” The room fell silent, as Josie had just stumbled onto the true root of her pain. “You know,” one of the mothers slowly began, “I’m not sure who will care for my daughter when her father and I are not here anymore. The thought makes me physically sick.” Another responded, “I’ve often thought that I want to live exactly one day longer than my son.” Perhaps in recognition that closure does not exist, they resisted the temptation to offer empty words suggesting otherwise. Instead, the mothers held space for the shared, terrifying reality that their children would likely outlive them all.

As a cold April melted into May, the warm weather hinted at the impending end of the academic year. In group, Josie was explaining that Oliver becomes dysregulated when confronted with endings, specifically, with the final day of any meaningful experience such as summer camps, academic years, or even family vacations. Consistent with his history, Oliver had decided that he was not going to participate in the graduation ceremony. Struggling again to temper her mastery, Josie brought a list of interventions to the group in order brainstorm solutions and get feedback about the efficacy of her ideas. The mothers were happy to swap strategies that had worked to support their own child through stressful events, but to each suggestion, Josie explained why it would not work. After some time, it was clear that everyone was becoming frustrated. Eventually, another mother responded, “Is it possible that you just can’t fix this? Even though, maybe for a different kid, your strategies would be really helpful?” Josie lowered her eyes back to her list and then slowly began to fold it back up. After a moment of tense silence, she looked up and said, “I just really wanted this one.” In response, the other mothers immediately validated her sadness and her desire to see her son graduate from high school. With a heavy heart, she responded, “Like so many other times, we’re just on his unique path, and it is what it is. But this one’s gonna hurt.”

Final Phase

Hope can be defined as “a belief in a future good” (Boss, 2006, p. 177). As part of our last session, I wanted to discuss what hopes the mothers had for themselves or their children after graduation. I noticed Josie was not there, which was unusual. Nevertheless, I began the group. I was about to turn the discussion over to the parents when Josie burst through the door, out of breath and laughing. “I’m so sorry,” she said while plopping herself into an empty chair, “but I was just in the principal’s office! Turns out my little hot tamale was caught kissing in the stairwell when he was supposed to be in class!” Josie went on to explain that cutting class to kiss a crush and getting caught in the act was such a typical high school experience that she couldn’t help but delight in the entire turn of events. As the conversation died down, I returned the group to the topic of sharing their hopes for the future. When it was Josie’s turn to share, she replied, “I hope Oliver can keep surprising me like he did today. Our kids can do so much more than we think sometimes. My biggest hope is for more happy surprises.”

Implementation of Coping Strategies

Graduation day arrived. While securing the graduates’ caps with bobby pins, I kept one eye on the door, but Oliver never arrived. On scanning the auditorium, I was surprised to see Josie sitting in the back row by herself and I went over to greet her. “Well,” she began, “Oliver is home with his dad.” I nodded. “How are you holding up?” “I’m definitely feeling it all. This day is both miraculous and heartbreaking. But I wouldn’t miss his graduation for anything in the world, even if he’s not here to graduate.” I replied, “Oliver is graduating today, and we are going to honor and celebrate all his accomplishments. I’m so glad you’re here. You have so much to be proud of.” Josie wiped her tears and offered up a cupped hand as if to make a toast. “To future happy surprises?” Raising my “cup” to meet hers, I responded, “To future happy surprises.”

Discussion

In this case, a support group with an ambiguous loss framework was a helpful intervention that resulted in increased resiliency for the members of the group. Prior to the intervention, Josie was experiencing a normal response to living with ambiguous loss but did not have the framework to conceptualize her experience and cultivate self-compassion. Through the group process, Josie enhanced her ability to identify when the discomfort of the ambiguity was driving her desire to control or fix an unfixable situation. Additionally, Josie learned the value of acknowledging her ambivalent thoughts and emotions. However, despite her progress, one cannot conclude that Josie’s struggles are over. Ambiguous loss does not have an end or a resolution, and Josie’s life is no exception. Still, her enhanced capacity to hold the pain of ambiguous loss in one hand while toasting to the possibilities of tomorrow in the other suggests she will be able to confront her next parenting challenge with enhanced understanding, self-compassion, and resilience.

There are limitations to this study. First, in my leadership position at a small private school, the executive director encouraged me to envision and implement a variety of parent support programs. I recognize that many school social workers will not have that directive, scheduling flexibility, or monetary support. I am hopeful that this case study will encourage school leaders to consider the value of the intervention and look for avenues that allow for support group implementation. Second, while the group members included a Black woman and several women of color, “Josie” was composed from middle-class White women. When I reflect on Josie’s ongoing struggle to adjust mastery, I realize that it is likely a result of her privileged position as a White woman that she consistently presented as needing to temper, rather than increase, her mastery. It would be interesting to see if this issue would be as prevalent in a support group that did not contain individuals who had experienced success securing their demands due, in part, to their privileged position in society. As it is impossible for social dynamics related to race and power to simply be “left at the door,” it is critical that the facilitator monitor how these factors influence the group process. However, as individuals living with ambiguous loss struggle to temper mastery regardless of their racial or cultural background (Boss, 2006), the examples are nevertheless significant and illustrate the importance of assisting individuals in this area.

Implications for Practice

Because of my role as both the group facilitator and supervisor of the school’s transition team, I was able to confirm that personal growth in the group frequently contributed to meaningful progress on a student’s transition plan. For example, through the group process, Josie recognized that her desire for Oliver to attend an exclusive university did not stem from the viability of the option but rather from a normal response to ambiguous loss. Once she understood this, we were able to move forward on a person-centered transition plan where Oliver and his goals were appropriately prioritized and centered. This contrasts with a typical model whereby the school provides struggling parents with increased technical support in the form of checklists, timelines, and contact information for community resources. While these are certainly helpful, logistical support alone may contribute to a parent feeling more overwhelmed, resulting in further disengagement from the transition process. Consequently, for schools to effectively collaborate with parents to move a student from school to post-school activities as mandated by the IDEA, schools would benefit from increasing their capacity to meet the emotional needs of parents during the transition process.

Upon reflection, there is a component of the group process that I would do differently in the future. As documented previously, in two-parent, heterosexual relationships, mothers tend to have more caretaking responsibilities of children with disabilities than fathers (Sharabi & Marom-Golan, 2018). However, this was not a topic that I introduced directly with the group. While we discussed ambiguous loss and their roles as parents, I did not steer the group towards deeper exploration of the uniqueness of motherhood, nor the ramifications of higher caretaking responsibilities on their well-being or personal relationships. While this caregiving discrepancy may not have applied to every group member, I nevertheless believe an opportunity was missed for meaningful reflection that could have been helpful for Josie as well as the other group members.

While this case study focused on parents of autistic adolescents, there is a growing body of research exploring the phenomena of ambiguous loss in many other areas of social work practice, such as within the child welfare system (Mitchell, 2016), in families where a loved one is living with Alzheimer’s disease (Dupuis, 2002) and most recently, in response to the myriad of loses many experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Leone, 2021; Walsh, 2020), to name a few. It is my hope that this article will contribute to social worker awareness and increased capacity to implement effective strategies that result in better outcomes for those living with ambiguous loss.

Conclusion

Some parents of autistic adolescents may be living with ambiguous loss which can contribute to parental suffering and enhanced difficulty planning for the future. When a parent is feeling hopeless about their child’s future, shameful and confused about their ambivalence, determined to fix an unfixable situation, or immobilized by indecision, parents are not able to effectively partner with their child to plan for adult life. While it is not possible to generalize findings from a case study, this article nevertheless illustrates a novel approach that social workers can consider, and if appropriate, integrate into their support strategies for struggling parents of autistic children during adolescence and the transition to adulthood. However, additional research is required to determine if this approach is generalizable on a larger scale. Future research should explore if the intervention positively affects the mother/child relationship, the well-being of the child, and the short-term outcomes of the transition plan. Lastly, while the research documents that mothers of autistic children have more caregiving responsibilities than fathers, one might deduce that, by extension, mothers have increased transition planning responsibilities. Research should examine if this is the case, factoring in not only the logistical tasks of transition planning but also the emotional labor that is inevitably a part of the process.

Autistic individuals are not lives to be grieved; rather, they are people who have fundamentally different neurology than those without autism and, as a result, will not experience their lives or relationships in the way their neurotypical parents expected. Social workers and other clinicians can assist parents to process this difference by offering a framework to view their experience and providing opportunities for them to access peer support. By doing so, parents can witness the gifts of their unexpected parenting journey and can better celebrate and champion the unique and singular life of their beloved child.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychological Association (2021). Disability. Retrieved from https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/disability.

Ankeny, E. M., Wilkins, J., & Spain, J. (2009). Mothers’ experiences of transition planning for their children with disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 41(6), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990904100604

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544–559.

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous loss: Learning to live with unresolved grief. Harvard University Press.

Boss, P. (2006). Loss, trauma, and resilience: Therapeutic work with ambiguous loss. WW Norton & Company.

Boss, P. (2007). Ambiguous loss theory: Challenges for scholars and practitioners. Family Relations, 56(2), 105–110.

Boss, P. (2016). The context and process of theory development: The story of ambiguous loss. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 8(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12152

Boss, P. (2017). Ambiguous loss treatment and interventions for family therapists [Webinar]. National Council on Family Relations. Retrieved from https://www.ncfr.org/ncfr-webinars/ambiguous-loss-treatment-and-interventions-family-therapists

Boyd, B. A. (2002). Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(4), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576020170040301

Bravo-Benítez, J., Pérez-Marfil, M. N., Román-Alegre, B., & Cruz-Quintana, F. (2019). Grief experiences in family caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder (AUTISM). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234821

Bromley, J., Hare, D. J., Davison, K., & Emerson, E. (2004). Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. Autism, 8(4), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361304047224

Brown, J. M. (2013). Recurrent grief in mothering a child with an intellectual disability to adulthood: Grieving is the healing. Child & Family Social Work, 21, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12116

Bruce, E., & Schultz, C. (2002). Non-finite loss and challenges to communication between parents and professionals. British Journal of Special Education, 29(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.00231

Cascio, M. A. (2012). Neurodiversity: Autism pride among mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.3.273

Çelik, H., & Ekşi, H. (2018). Mothers’ reflections of ambiguous loss on personal family functioning in families with autistic children. Ankara Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Fakültesi Özel Eğitim Dergisi, 19(4), 723–745. https://doi.org/10.21565/ozelegitimdergisi.383589

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1

Cheak-Zamora, N. C., Teti, M., & First, J. (2015). ‘Transitions are scary for our kids, and they’re scary for us’: Family member and youth perspectives on the challenges of transitioning to adulthood with autism. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28(6), 548–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12150

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 100.

Dupuis, S. L. (2002). Understanding ambiguous loss in the context of dementia care: Adult children’s perspectives. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 37(2), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v37n02_08

Ferguson, P. M., & Ferguson, D. L. (1993). The promise of adulthood. In M. E. Snell (Ed.), Instruction of students with severe disabilities (4th ed., pp. 588–607). Macmillan.

Foody, C., James, J. E., & Leader, G. (2015). Parenting stress, salivary biomarkers, and ambulatory blood pressure: A comparison between mothers and fathers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(4), 1084–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2263-y

Hartley, S. L., & Schultz, H. M. (2015). Support needs of fathers and mothers of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), 1636–1648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2318-0

Hastings, R. P., Beck, A., & Hill, C. (2005). Positive contributions made by children with an intellectual disability in the family: Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 9(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629505053930

Ho, H., Fergus, K., & Perry, A. (2018). Looking back and moving forward: The experiences of Canadian parents raising an adolescent with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 52, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rautism.2018.05.004

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004, 20 U.S.C. § 1400. (2017). Retrieved from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.43

Jackson, J. B., Steward, S. R., Roper, S. O., & Muruthi, B. A. (2018). Support group value and design for parents of children with severe or profound intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(12), 4207–4221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3665-z

Krishnan, R., Russell, P. S., & Russell, S. (2017). A focus group study to explore grief experiences among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 43(2), 267–327.

Leone, R. A. (2021). Using ambiguous loss to address perceived control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Counseling and Family Therapy Scholarship Review, 3(2), 4. https://doi.org/10.53309/ZLPN6696

Lustig, D., & Thomas, K. (1997). Adaptation of families to the entry of young adults with mental retardation into supported employment. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 1997, 21–31.

Mitchell, M. B. (2016). The family dance: Ambiguous loss, meaning making, and the psychological family in foster care. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 8(3), 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12151

Moses, K. (1987). The impact of childhood disability: The parent’s struggle. WAYS Magazine, 1, 6–10.

O’Brien, M. (2007). Ambiguous loss in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Family Relations, 56(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00447.x

Pelchat, D., Lefebvre, H., & Perreault, M. (2003). Differences and similarities between mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of parenting a child with a disability. Journal of Child Health Care, 7(4), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935030074001

Robison, J. E. (2019). Talking about autism—thoughts for researchers. Autism Research, 12(7), 1004–1006. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2119

Roux, A., Shattuck, P., Rast, J., Rava, J., & Anderson, K. (2015). National autism indicators report: Transition into young adulthood. Life course outcomes research program, A. J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University. Retrieved from https://drexel.edu/autismoutcomes/publications-and-reports/nat-autism-indicators-report/

Scorgie, K., & Wilgosh, L. (2011). Parents’ experiences, reflections, and hopes as their children with disabilities transition to adulthood. Interdisciplinary Journal of Family Studies, 16(2), 55.

Shakes, P., & Cashin, A. (2019). Identifying language for people on the autism spectrum: A scoping review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1522400

Sharabi, A., & Marom-Golan, D. (2018). Social support, education levels, and parents’ involvement: A comparison between mothers and fathers of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 38(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121418762511

Sinclair, J. (2012). Don’t mourn for us. Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies, 1(1), 1.

Timmons, J. C., Whitney-Thomas, J., McIntyre, J. P., Jr., Butterworth, J., & Allen, D. (2004). Managing service delivery systems and the role of parents during their children’s transitions. Journal of Rehabilitation, 70(2), 19.

Walsh, F. (2020). Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: Meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Family Process, 59(3), 898–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12588

White, N., & Hastings, R. P. (2004). Social and professional support for parents of adolescents with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(3), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2004.00197.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I have no known conflict of interest or funding to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chase, B. The Unexpected Comfort of Feeling It All: A Support Group for Mothers of Autistic Adolescents Using the Lens of Ambiguous Loss. Clin Soc Work J 50, 436–444 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-022-00834-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-022-00834-2