If you've lived in Denver or moved here during the past 10 years, you probably have a sense that the city has transformed.

We wanted to see if we could watch Denver growing up during the past decade, so we dug into the assessor's records to chart the changing footprint of tall buildings within the city.

The map above shows what we found about how Denver's skyline has grown since 2010, and it's increasingly creeping beyond the downtown corridor. Cherry Creek and the Tech Center also got a little taller.

For some, this is great news. Mayor Hancock celebrated tons of new construction off Brighton Boulevard as "multi-billion dollars worth of investment" earlier this year, and some who worry about the city's high cost of living are glad we're developing housing density. For others, it's a sign of unbridled growth and the baggage that comes with it.

Five Points is case-in-point for mixed emotions.

The neighborhood once known as "the Harlem of the west" has long been central to discussions about displacement in Denver. It also saw a whole lot of development since 2010.

Data Source: Denver Assessor's Office

A lot of that construction happened on the Brighton side, an industrial area whose legacy businesses have all but disappeared from the corridor. But Denver's tall buildings have also steadily marched up Welton Street, the heart of Five Points' human side.

For Brother Jeff Fard, a longtime activist and journalist in the neighborhood, the height edging into his neighborhood is not a good omen.

"What your map shows is the mindset of city leaders who have decided that they will open up this city to the highest bidder, cranes everywhere," he told us. "I'm not opposed to all of all of that or any of it, but I am opposed to the unequal distribution of space."

Fard said his concern with Welton Street's new "concrete canyon" goes beyond the displacement of Black Denver from the once-redlined area. It's about dense apartment blocks filled with young professionals replacing homes with yards where kids once played.

"This is not a family city. This is, 'I'm going to stay here until my next stop on this journey called life.' It's not built for seniors. It's not built for folks that have challenges in terms of their mobility. It's not built for individuals that just might be working class," he said. "People are moving here because of opportunity ... I guarantee you most of those individuals are not saying, 'I want to settle down here. This is where I want to raise my family. This is where I want to plant my flag.' A lot of individuals are not saying that. And if they are saying it, it's because they can afford to have that conversation."

Kris Christensen, a professor of urban geography and planning at the University of Colorado Denver, said "we do need to densify our city" to address the housing shortage.

But it can come at a cost, she added.

The new, tall apartment buildings on Welton and Brighton might give newcomers a place to live, but they may not create the right conditions communities to grow and find a long-term stake in the area. Christensen said "place attachment" is the technical term for the love and care that makes a neighborhood last.

"When you care about place, you stick around. And it's incredibly possible to make placeless places. I think RiNo is a great example of that. It appeals to the late Millennial and Gen Z-er. And it has bars. That's all I see going on for those neighborhoods, so they're going to be transitory," she said. "I think [Fard] was spot on to say these are not being designed and built to help the neighborhood continue to be a vibrant place."

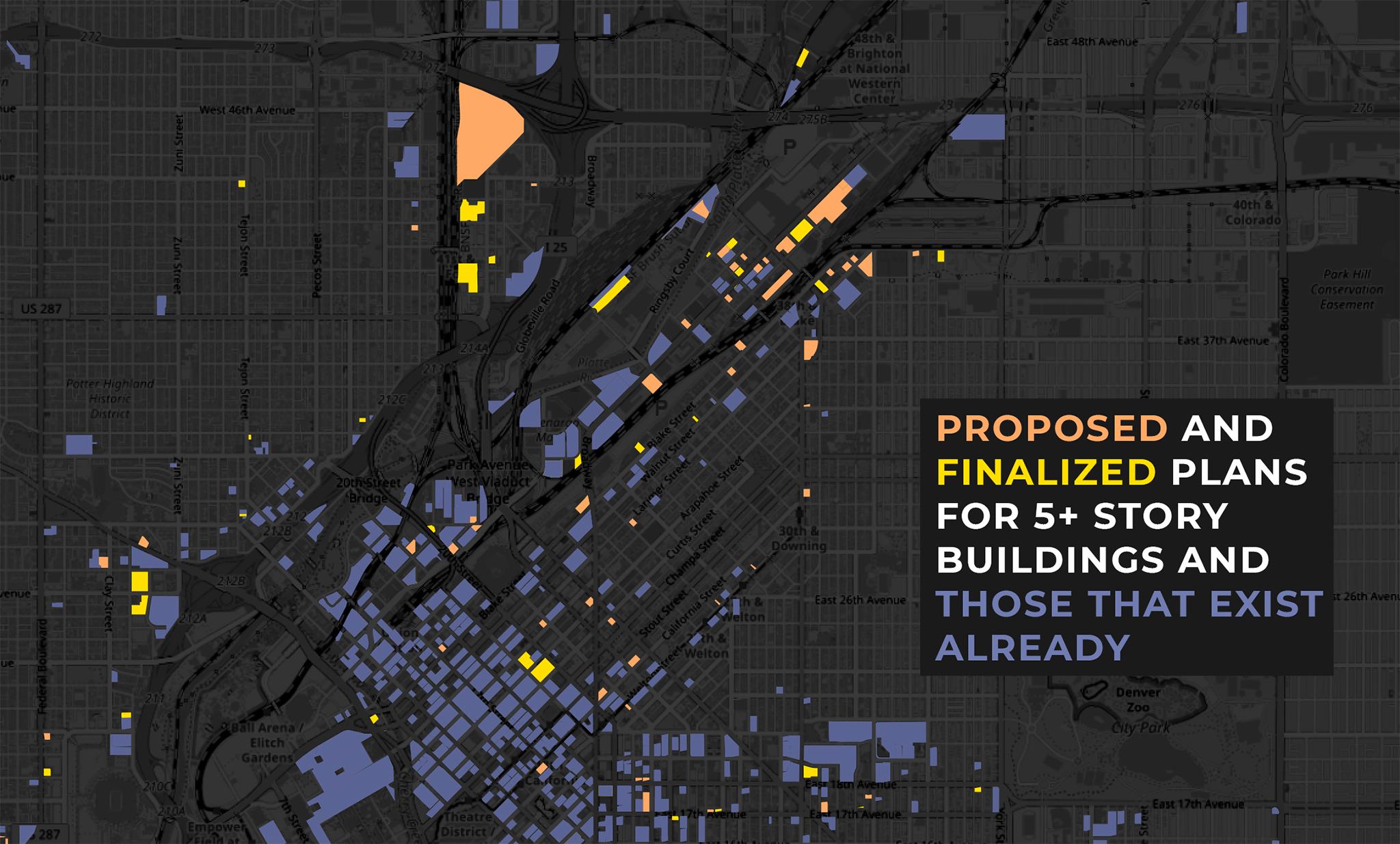

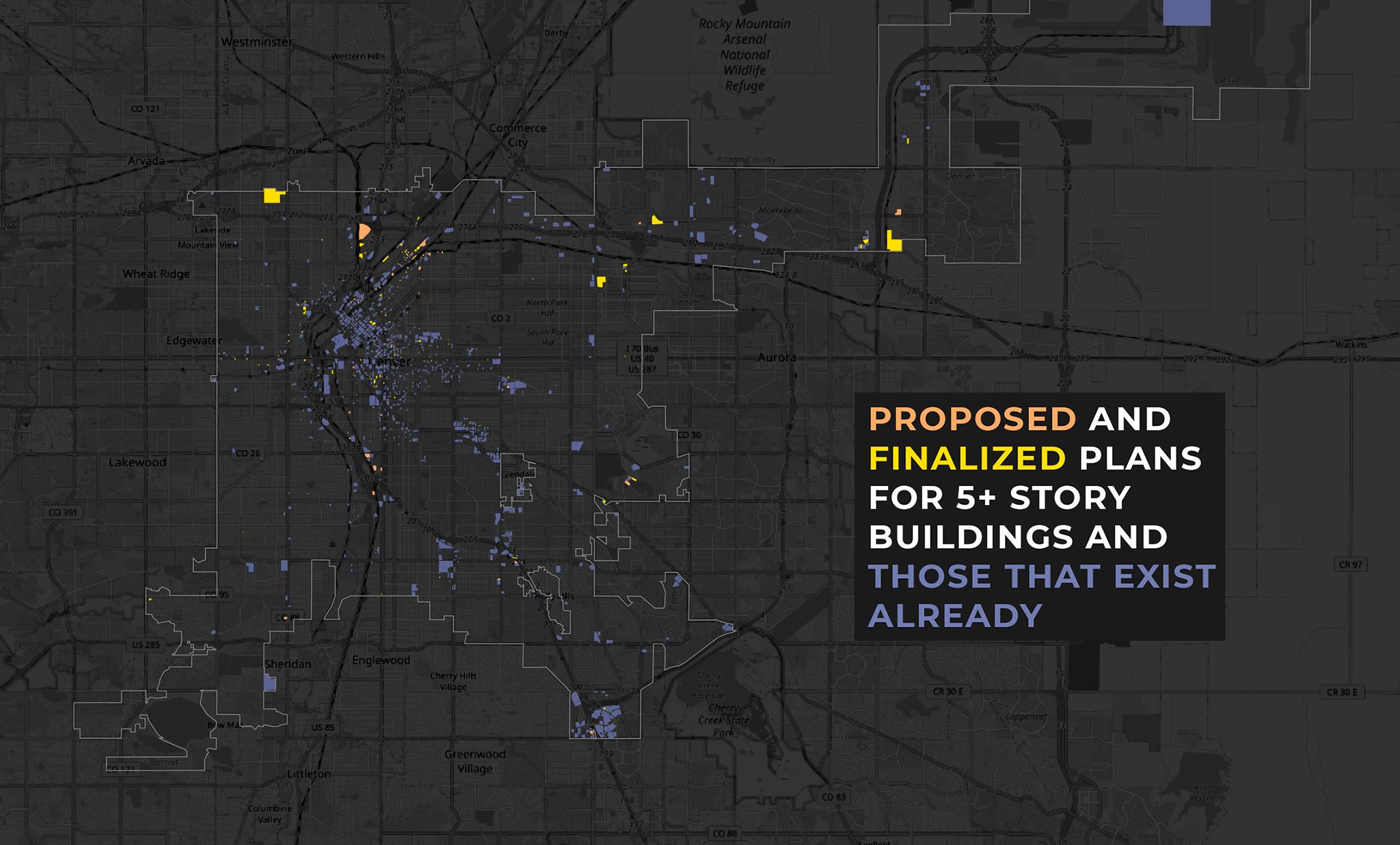

Brighton, which stretches into Elyria Swansea, will continue to see more of this construction. We also mapped final development plans and early concepts to see what the future might look like, and a cluster of those projections surrounded the northern end of that corridor.

A quick note about this plan map: Anyone can submit a design proposal to the city, even if they don't own the property in question. While the "finalized" plans will result in construction, the "proposals" just mean someone was thinking about it.

Data Source: Denver Assessor's Office

We went for a walk on Brighton to talk to people who live there. Two couples we ran into within five minutes of each other both said they moved to Denver in the last two months, liked the neighborhood but doubted they'd stay for too long.

Reuben Jalbert, who was visiting one of the couples and had "literally" only been in town for an hour, said the west side of RiNo felt like other neighborhoods in a lot of other cities. His first impressions of the place didn't sound too far off from Fard's and Christensen's.

"This isn't a place where you want to raise a family. And if you don't have multi-generations in a concentrated spot, everybody seems to be just about themselves," he said. "I think you need more community space."

The growing spots on our map might not be the problem, compared to the places that remained dark.

According to a 2021 report from Root Policy Research, Colorado as a whole needs to add about 41,000 homes per year between now and 2030 to keep up with demand but is so far projected to fall short (see page 6). While we might be a big state, a lot of that burden will fall on the metro.

"We have a responsibility of being a leader in how our region accommodates growth," Laura Swartz, spokesperson for Denver Community Planning and Development, told us in an email. "As the region's primary city, Denver has the most urban neighborhoods, with some of the largest infill development sites."

Robert Greer, an eviction defense attorney and an urban design advocate, told us he believes density is the only responsible way to stem displacement in the city. An environmentalist, he said growing out, instead of up, would crush Colorado ecosystems and render us a less sustainable city than we could become. He pointed us to a 2018 International Panel on Climate Change report that says "higher population densities," especially those where people can work where they live, are "strongly correlated with lower [greenhouse gas] emissions" (see page 30).

Data Source: Denver Assessor's Office

While he generally disagreed with Fard, and thinks there should be more, dense residential buildings in town, he did say this growth should be happening in more places.

"There's not a way around the housing crisis without building a hell of a lot of more houses," he said. "Certainly, if we started in wealthier neighborhoods building more multi-family, that would be great."

Data Source: Denver Assessor's Office

Even if that development is intended for people looking for luxury accommodations, Greer said Denver's demand is high enough that those non-affordable units could take pressure off working-class neighborhoods. He pointed to one report from New York University, which said "new construction is crucial for keeping housing affordable," even if it's high-end, because a shortage of supply even at the luxury level will ripple through the market (see page 7).

Our tall-buildings map does show growth expanding from Denver's downtown, but there's not a ton that exists or is planned for most of the city's neighborhoods. It's one reason Greer supports a high-density development at the Park Hill Golf Course, a chance to spread the love elsewhere, though Fard and others view plans there as a developer's ploy to "fleece" the city.

Data Source: Denver Assessor's Office

While new affordable units have been opening recently around town, a lot of planned density is going up in areas that won't be so cheap. The "golden triangle" area between Civic Center, Speer Boulevard and Broadway is filled with cranes helping to construct buildings in the area.

Veronica Salazar, who moved to the area a few years ago after leaving an apartment in RiNo, said she loves the area because it feels like a neighborhood. She also wonders if all the new development might spoil things.

"It still feels kind of neighborhoody to me. It doesn't feel as, you know, city-ish," she said. "I definitely see myself staying in this neighborhood for at least another year or two. And then we'll see what the housing market looks like, and then I'd probably be looking to buy after that."

Things are changing, she told us. And her dog, Kyree, needs a yard.