“It is only in his music, which Americans are able to admire because protective sentimentality limits their understanding of it, that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story. It is a story which otherwise has yet to be told and which no American is prepared to hear.”

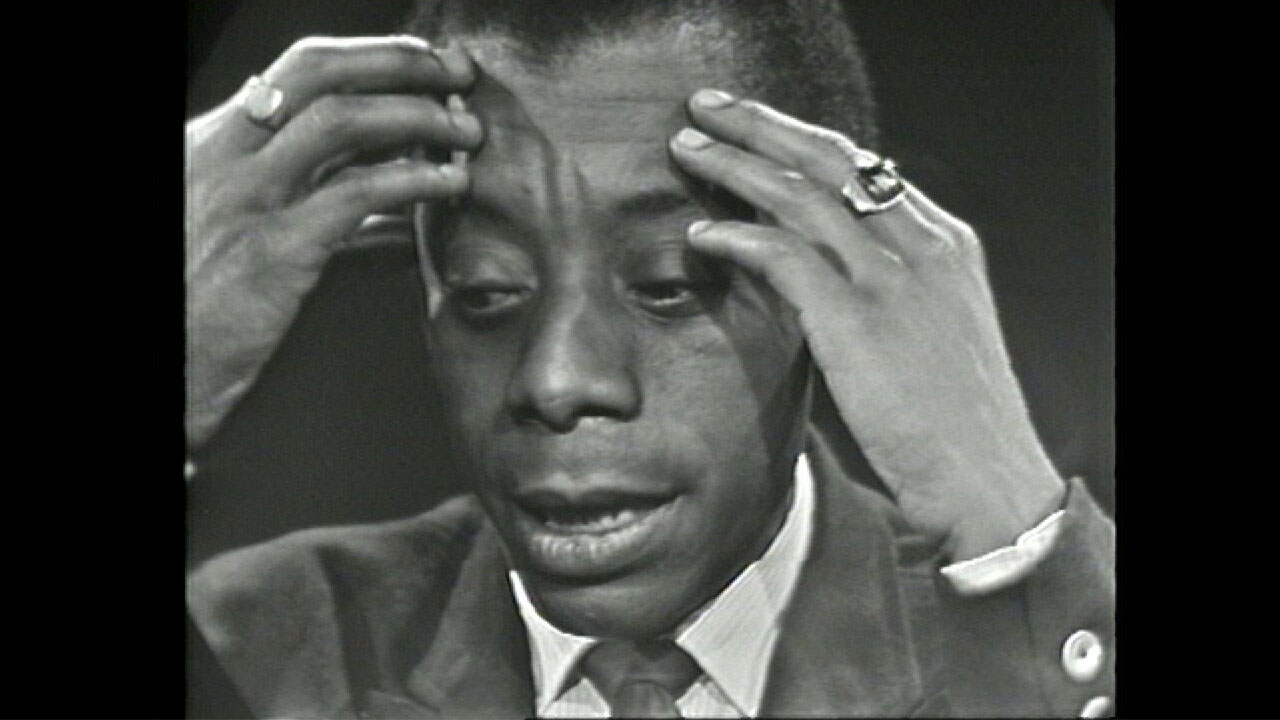

—James Baldwin, “Many Thousands Gone”

That sound.

James Baldwin’s words burst in my gut when I heard that sound. Here I was in Paris, France, attending the 2008 theatrical production of “Sonny’s Blues” by Word for Word. Led by director Margot Hall and composer Marcus Shelby, this Oakland-based troupe captured every single word of Baldwin’s text on stage and accompanied it with live music. Published in 1957, the short story recounts a tense relationship between two African American brothers: one unnamed brother is a middle-school teacher who works to climb the social ladder and assimilate into mainstream American culture; the other brother, Sonny, is a jazz pianist who draws on his music to flee prejudice, poverty, and drug addiction in mid-20th century Harlem.

Though “Sonny’s Blues” explores aspects of African American experience in Harlem, Baldwin composed it while ensconced in post-WWII Paris. Word for Word’s 2008 performance brought it back to its compositional home. I thought I had gone to Paris to investigate African American jazz musicians and jazzophiles like James Baldwin in their Parisian migrations. Little did I know that, like Baldwin’s, my journey abroad would throw me right back into my homeland.1 I got dropped right back in it at the moment of that sound.

I was already shaken by the oral storytelling of the murder of the brothers’ uncle in a hit-and-run accident by young, drunken white men. Baldwin writes:

“Your father says he heard his brother scream when the car rolled over him, and he heard the wood of that guitar when it give, and he heard them strings go flying, and he heard them white men shouting, and the car kept on a-going and it ain’t stopped till this day. And, time your father got down the hill, his brother weren’t nothing but blood and pulp.”2

This passage describes the end of a scene in which Sonny’s uncle and father are out carousing and laughing as they walk back home. The fun transforms into horror, as a car of white men run the uncle down. The car speeds away, leaving his broken body dead in the street. Dismembered and dislocated. But blood and pulp. This moment seems the utter failure of U.S. democracy. If democracy espouses the meeting of disparate minds and diverse bodies into compromised union, this encounter between two segregated racial communities ends in white America’s dissolution of democratic potential in this mid-century moment. For when these two racialized communities meet, vicious and uncaring murder is the result.

And yet sadly this violence against the black body is the repeated result of U.S. attempts at democracy. In his 1903 groundbreaking work Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois discussed the violent repercussions dealt to African Americans seeking freedom and social uplift. Taking on the perspective of a white American judge, Du Bois wrote:

“Now I like the colored people, and sympathize with all their reasonable aspirations; but you and I both know, John, that in this country the Negro must remain subordinate, and can never expect to be the equal of white men […] But when they want to reverse nature, and rule white men, and marry white women, and sit in my parlor, then by God! We’ll hold them under if we have to lynch every Nigger in the land.”3

Even 40 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Du Bois sees the psyche of white America as still not ready for racial equality. Here he describes the placating manner of white America that may offer kindness but not when de facto equality is sought. The reflexive response is to draw on lynching as a repeated and repeatable remedy for dissent against the U.S. social order.

Still today, the threat of violence to black bodies seems inherent to the experience of being raced. Ta-Nehisi Coates reminds us of the physically traumatic impact of racism when he cautions his son that racism “dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this. You must always remember that the sociology, the history, the economics, the graphs, the charts, the regressions all land with great violence upon the body.”4 Coates describes the blows that racism lands—such that it is not only a psychological battering but also an invisible, silenced, and ignored physical trauma on the black body.

From then ’til today, James Baldwin fits within a lineage of black male intellectuals making the broken black body visible. His words enact racialized violence, making us feel and imagine that pain as we read. His words disrupt, dismember and dislocate the black body.

From then ’til today, James Baldwin fits within a lineage of black male intellectuals making the broken black body visible. His words enact racialized violence, making us feel and imagine that pain as we read. His words disrupt, dismember and dislocate the black body. They highlight other less apparent beatings on the black body too, such as the effects of internalized racism and the results of institutionalized racism. For example, the result of the uncle’s murder forges hatred in the father who remains. The father is forever mentally impacted by the murder of his brother: “He says he never in his life seen anything as dark as that road after the lights of that car had gone away. Weren’t nothing, weren’t nobody on that road, just your Daddy and his brother and that busted guitar. Oh, yes. Your Daddy never did really get right again.”5 Witnessing his brother’s death prompts psychological dislocation in the father. He is traumatized, so much so that he carries the memory of murder along with him forever.

Meanwhile remnants of this encounter, this democratic misencounter really, are shared with the two brothers trying to make their way in the world. The uncle’s physical dislocation and the father’s psychological dislocation shape their worldview. The brothers attempt to escape the “menaces” of society such as ghettoization, drugs, and crime that grow out of institutionalized racism.6 Sonny and his brother decide to leave their childhood home. Perhaps their voluntary geographical dislocation will offer freedom finally? Sadly no. Even with geographical distance, Baldwin demonstrates how trauma follows. The dismemberment of the uncle’s body is not a singular moment of racialized trauma. Baldwin suggests a ripple effect with his description of geographical dislocation as “amputation.”7 He vividly details the brothers’ own trauma as one of separation from their childhood home in the Harlem ghetto: Sonny and his brother sit enclosed in the car as they ride past the “menaces” outside, in Baldwin’s words “toward the vivid, killing streets of our childhood.”8 Baldwin continues by comparing the brothers’ escape and dislocation from Harlem with amputation and leaving behind a limb. He writes: “Some escaped the trap, most didn’t. Those who got out always left something of themselves behind, as some animals amputate a leg and leave it in a trap. […] It is always at the hour of trouble and confrontation that the missing member aches.”9

This particularly violent metaphor suggests a brutal and painful psychological tearing away from one’s upbringing and heritage. Baldwin’s language choice as some animals amputate a leg and leave it in a trap riffs on Fanon’s phrasing in his 1952 book, Black Skin, White Masks. In the chapter titled “The Facts of Blackness,” Fanon writes:

“I discovered my blackness, my ethnic characteristics; and I was battered down by tom-toms, cannibalism, intellectual deficiency, fetichism, racial defects, slaveships. … I took myself far off from my own presence, far indeed, and made myself an object. What else could it be for me but an amputation, an excision, a hemorrhage that spattered my whole body with black blood? But I did not want this revision, this thematization. All I wanted was to be a man among other men.”10

Here Fanon describes his internalization of racialization and the toll that a history of racialized perceptions, expectations, and oppressions has taken on him psychologically. His words envisage a ripping away from his sense of self and a desire to be perceived as human rather than dehumanized by racialized difference.11

Baldwin’s use of amputation augments Fanon’s psychological dislocation. As the brothers revisit their childhood haunts, they long for their home and experience the resulting tear caused by their geographical dislocation. By using such visually and viscerally strong language as amputation, Baldwin links the experience of separation from home to the uncle’s separated body, his dismemberment. Baldwin suggests that even geographical separation cannot erase or dissipate the memory of the psychological dislocation that racism produces. With these scenes, Baldwin links physical, psychological and geographical dislocation. “Sonny’s Blues” reminds us of the many brutal dislocations that racism and racialization cause. Many traumas come to us via memory and reality. They come and they come. … and they come to be repeated.

I thought I had gone to Paris to investigate African American jazz musicians and jazzophiles like James Baldwin in their Parisian migrations. Little did I know that, like Baldwin’s, my journey abroad would throw me right back into my homeland. I got dropped right back in it at the moment of that sound.

This realization became most clear to me with my own experiences of dislocation. For me it took the marriage of Baldwin’s words with migration and music—which takes us back to that sound. And back to Paris and Word for Word’s enactment of “Sonny’s Blues.” As the mother recounted the uncle’s horrific death, that sound changed me. The music started in a murmur as the mother recalled the uncle’s lively singing voice. Gradually we could hear the bass and piano crescendo into a fluid movement, almost replicating the sound of flowing layers of water falling on each other. This score accompanied the father and uncle’s explorations. Then the music altered dramatically with the uncle’s death. At the apex of the scene, crazy mutterings, whines, and tweaks of the horns in the band accosted us in the audience. The vibrations and pitch-crazy maneuvering elicited a visceral feeling of discomfort in me. The quartet’s live accompaniment rose to a fever pitch, drawing me into a shocking confrontation with the blood and pulp Baldwin’s words described. Everyone around me seemed to move beyond this traumatic moment. Even though the mother had described the uncle’s murder as a warning for the unnamed brother to look out for Sonny, both brothers still struggled to understand and support each other. Instead of holding onto the gravity of their mother’s story, they began to bicker over what jazz really was. One could almost see Sonny shaking his head in disappointment at his brother’s acknowledgement of Louis Armstrong instead of Charlie Parker as the go-to jazz pioneer. The audience shifted their attention too. Afterwards, several said they enjoyed the manner of Word for Word’s exact replay of Baldwin’s words. Others vibed with Shelby’s vibrant musical interpretation of the text. While yet others marveled at the newfound knowledge of Baldwin’s work that they took away.12 Momentarily enthralled, they all moved on.

But not I.

I was still stuck in that moment of shrieking, in the echoes of musical and emotional brokenness. I felt isolated, made vulnerable by the still aching disease prompted by the cacophonous band play. Despite my disease, despite this moment of dislocation, the marriage of Baldwin’s words, Shelby’s sound, and my geographical dislocation in Paris spawned a productive space in me. Word for Word’s performance threw me into an alternate space, un lieu de mémoire that plunged me into an imagining of historical racialized trauma.13 Word for Word’s performance and Marcus Shelby’s score forged a bridge across historical and geographical discontinuities in “Sonny’s Blues”: For the story features a sequence of moments in the brothers’ lives in 1940s Harlem, New York. And, it is a 1950s short story composed by Baldwin in Paris. And, while Baldwin dialogues with the work of Frantz Fanon in his 1950s residency in Paris, Fanon is recalling the assault of racism on his black, Martiniquan body in Lyon, France. “Sonny’s Blues” layered and put in dialogue these remembered moments and locales; it located racialized trauma in all of them and forced comparison and confrontation in one alternate space. Baldwin used his writing to present blues and jazz as tools for getting to and moving through this space of trauma. In this lieu de memoire, Marcus Shelby’s music combined with word and migration to prompt a way to survive despite the debilitating, silencing, and breaking nature of racialized trauma. For music was Baldwin’s way out of the trauma or at least his way to make it visible. He once wrote, “For the horrors of the American Negro’s life there has been almost no language.”14 Shelby’s score provided an attempt at language, which Baldwin describes to the best of language’s limits in the epic performance of Sonny’s piano play at the end of the short story.

As I watched “Sonny’s Blues” in 2008 Paris, the crazy mutterings of that jazz quartet also connected me to 2005 Paris. I had seen news reports on the fires and ensuing riotous encounters with French residents of African descent marginalized in the banlieues and protesting in dissent.

Shelby’s sound and Baldwin’s words shook me up. They located racialized trauma in a very real way that I could feel. As I watched “Sonny’s Blues” in 2008 Paris, the crazy mutterings of that jazz quartet also connected me to 2005 Paris. I had seen news reports on the fires and ensuing riotous encounters with French residents of African descent marginalized in the banlieues and protesting in dissent. And I had wondered: Had Baldwin’s fire next time realized itself again? Had I witnessed another recurrence of racialized trauma? And more importantly, what had I done about it? I was studying in the Latin Quarter, only a five-minute walk away from the Sorbonne and the hallowed stomping ground of the French intellectual elite. Technically it was the same Paris as the fiery revolts I watched on the news. Still there was a geographical dislocation between us. The agitation erupted in banlieues circumscribing northern Paris, and police stringently pushed out attacks on the touristy inner shell of Paris that I inhabited. And there were other equally prominent differences—class, ethnicity, religion. But we shared a history of marginalization and suppression. As I listened to the news reports, I felt my own silence. Was my own witnessing stagnant, what could I do? The opening lines of James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket come to mind: “There are days, this is one of them, when you wonder what your role is in this country and what your future is in it.” It was one of those days.

This car was full of white men.

Vroom—stomp, stomp, stomp, stomp, stomp, stomp.

Said this car was full of white men.

Buh-doom, doom, doom, doom…vrooooom. Vrooooom!

And he heard them stings go flying

Buh-doom, doom, da-da, doom…Whooh! Whooh! Whooh! And his brother weren’t nothing

But blood

and

pulp.

I was in the thick of it again. In some alternate space where I was feeling the spirit of James Baldwin. Perhaps it was not clear to me then, but there was an energy surrounding me. An inspiration of what to say, sing, shout, spit and when to silence that came from Baldwin’s words. I sat facing a crowd of young and old, student and teacher, Latinx, Asian, Native American, white and black. All were waiting. The pulse before my next command was apparent. There was a reverberating silence as they waited for my next call to action—my next call for their response to Baldwin’s words and my inspired sounds with them. Here I was in Merced, California, participating in a panel discussion following the screening of James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket in February 2016. Filmmakers Karen Thorsen and Douglas Dempsey were touring the recently re-mastered film and prompting “Conversations with Jimmy” across the United States. Earlier in the day, I had given a lecture and performance at the University of California, Merced, on dislocation in “Sonny’s Blues.” Upon my arrival for the screening, the filmmakers greeted me and rallied for me to repeat my performance. Since I had already performed at the university, I was not prepared to perform again—only to comment on Baldwin’s legacy and contemporary relevance. So I was surely shaking in my boots at their request. This crowd, this new crowd, this unknown crowd, this crowd unaware of the context, how could I perform for them? Would I be able to convey the power of Baldwin’s words? Could I even follow his masterful, eloquent presence shared in filmic form? As James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket began, I sat and thought: Was today the day to accept “my role” in this country? Was my role to give voice, moreover, to give song to Baldwin’s sentiments? I had to try.

I first described the short story and began to recite the scene of the uncle’s murder. It began in fun fashion. Describing the uncle’s “fine voice” I held out the long i of the word as if commenting with delight about his looks.15 Baldwin’s description of the uncle as kind of “frisky” became a scatted guitar leitmotif that was filled with whimsy.16 That tune reentered at different points in the story, its exuberant mood working against the horror that would ensue. Then I began to incorporate the audience in the performance: Half of the audience came in with sustained hums that offered a baseline when prompted. When I signaled the other half, they stomped collectively—sometimes loud, fast, and overpowering and other times in a steady, walking mode. I continued reciting as the brothers started walking down the hill, laughing, chatting … and I filled in the gaps between the words with a musical baseline to accompany the father and uncle’s journey down the hill. Then a new element entered the scene. Upon saying “he heard a car motor,” I growled out the sounds of a car engine revving.17 These dark, low vroom sounds were countered with my high screams and whines that articulated the brother’s scream, the flying guitar strings, and the “great whoop and holler” of the white men.18 As the story built I layered these sounds and sporadically pulled in the audience for effect. The story reached a peak with “this car was full of white men” wherein the motor revving and feet stomping created a crescendo of thunderous sound.19 Such cacophony countered the end wherein blood and pulp was slowly spoken, with breath between each word, and a stunning, uncomfortable … silence.

It rested there in that beat of breath. The trauma. It weighed down on all of us, reminiscent of that heavy discomfort Baldwin’s words with sound had once conveyed in me. It was discomfort at the memory and tear of repeated racialized trauma. I was physically feeling it in that space. And through me so was the audience. One audience member said she felt as though in a movie—as if in surround sound I imagine, slowly moving through and to a reckoning. Another participant noticed the difference between the light-hearted and dark, somber mood created; the buildup of stomps and layering of sound took him on a journey that gradually intensified in its gravity. Another audience member had read “Sonny’s Blues” before, but this passage had not stood out. The performance made it come alive for her and prompted her to return to the text. Yet another audience member felt weighed down by the performance, unable to quite let go of that trauma and her involvement in it.20

So what is the way out of racialized trauma? What is the way out of the recurring punch of violence on black bodies? Middle passage’s chains … Slavery’s labored killings … Jim Crow’s lynchings … Civil Rights era’s acquitted burnings and slayings … and the hunting, frisking, stealing the breath of black men, women, and children in today’s U.S.A. Still today. In that ending silence, in those pauses between whines and song and guitar play, I entered the trauma. In that performance it was as if I was waging my own battle with this trauma, saying: While you may try to break, tear, erase my body, I am here. Despite the attempt to splatter my blood… I am here. Despite the dismemberment … I am here. Despite the distance from ancestors and resulting dislocation … I am right here. Yes, inspired by the lineage of black male intellectuals like Baldwin, but also nourished from Ida B. Wells to Audre Lorde to the three women co-founders of Black Lives Matter. My black, female body is right here. Intact, unsilenced, and ready to act. My role is to give body to Baldwin’s words. And in between them, ahhh in that potentially debilitating silence, my role is to step into trauma and sing through it. My role is to create witnesses to this violence on the black body. But not just witnesses, co-performative witnesses.21 In imagining and re-enacting this moment of historical racialized trauma, I am an observer of the effects of racialized violence on others but also on myself. I am “passive” such that I am internalizing that trauma but also “active” as I am acting in and against it. And I am not alone. I brought the audience in too—all of us complicit and affected by this violence, all of us forced to see and hear. And do.

His [Baldwin’s] was a patient love, but not without grave disappointment. For he realized that we were all miscommunicating brothers, listening past instead of to each other. Still Baldwin’s love was like the brother seeking the family’s nod of recognition, the jazz soloist waiting for the rhythm section’s sustaining next beat.

For James Baldwin has taught me that the way out of trauma is in. We must enter that which would try to break our black bodies, to question our very existence, to challenge our contribution to this American democ- racy. Baldwin had the choice in his own life to react in anger, to leave, to disavow his heritage. When he exiled to France in 1948, he fled the United States so that he would not enact violence, thus refusing to respond in like manner.22 For Baldwin’s path out of racialized trauma was always guided by love. His love was the vulnerable public sharing of personal racialized trauma despite his awareness that it grew out of national misencounters with democracy. His love reached out to share his accord and critique of our attempts at democratic union, whilst suspecting his offering would be trounced again and again.23 His was a patient love, but not without grave disappointment.24 For he realized that we were all miscommunicating brothers, listening past instead of to each other. Still Baldwin’s love was like the brother seeking the family’s nod of recognition, the jazz soloist waiting for the rhythm section’s sustaining next beat.

Baldwin’s love and hope for true democracy is most clear in his consistent attention to black music throughout his work. Especially in “Sonny’s Blues” Baldwin underscores the importance of music in embodying and relating racialized trauma. It is the way out and eerily the way into trauma. Perhaps it is due to what Baldwin calls the “double-edged” quality of black music, the joy and sorrow that even happy songs convey.26 That double-edge of black music expresses the pain and anger and yet, in the end, hope and love too. It is love with an edge. For it is not ignorant, nor all-accepting, but rather love that knows the challenges and still reaches out. Just as I reached out to perform despite uncertainty. It was a social love that guided me. A loving force that drew me to walk along Baldwin’s path and to witness what he described. Just as he had done, I strived to both witness and be a site of witnessing for violence on the black body.27 And I too recognized my entry point through music. Baldwin’s continual coming-to music, Sonny’s trance-like coming-to moment at the end of the short story, my entry alongside and in between Baldwin’s words with song, all of these moments come back to the power of music “to tell the story which no American is prepared to hear.”28 For Baldwin, Sonny and myself, the way to confront the traumatic racialized experience of being African American is by sounding out.