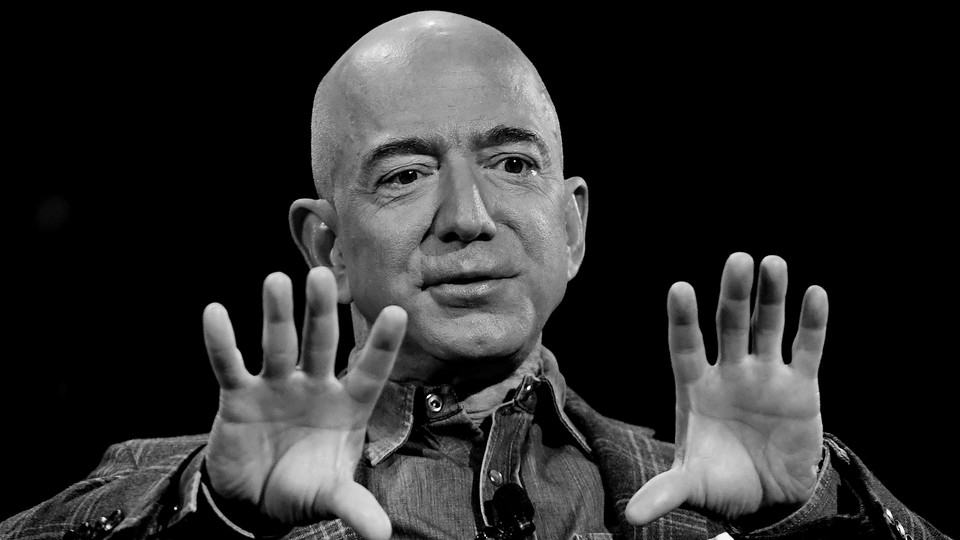

The Weekly Planet: How Jeff Bezos Is Spending His $10 Billion Earth Fund

These nine environmental groups are some of his first grantees.

Every Tuesday morning, our lead climate reporter brings you the big ideas, expert analysis, and vital guidance that will help you flourish on a changing planet. Sign up to get The Weekly Planet, our guide to living through climate change, in your inbox.

Back in February, Jeffrey Bezos posted a picture of the Earth on Instagram. In the caption, the world’s richest man announced his new project to save the world: the Bezos Earth Fund, an initiative to support scientists, activists, nonprofits, and anyone else who seems to have a good idea to fight climate change. “Climate change is the biggest threat to our planet,” the Amazon chief executive said. He committed $10 billion to the effort, and said he would begin issuing grants in the summer.

The fund portended a revolution: In pledging what was then more than 7 percent of his net worth, Bezos was, by any measure, eclipsing the total sum spent by American philanthropists on climate change in recent years.

Then the pandemic arrived. Amazon became a kind of private utility, and Bezos’s attention was diverted. Little has been heard about the fund. Months came and went without any grant announcements.

But that is soon to change. Throughout the summer, Bezos—sometimes joined by his girlfriend, Lauren Sanchez, a television producer—met via phone with environmental nonprofits and other advisers in the field, according to two people who work in climate philanthropy and have knowledge of the situation. He is now ready to start giving.

But Bezos’s gifts indicate that he isn’t trying something new on climate so much as boosting an ancien régime. Bezos is prepared to give $100 million each to four of the most established environmental groups in the country—the Nature Conservancy, the Environmental Defense Fund, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and the World Wildlife Fund, according to my two sources, who were granted anonymity so that they could speak candidly about the small world of climate giving.

Bezos has also committed $100 million to the World Resources Institute, a sustainability-research organization that operates globally, the two sources said.

And he has promised smaller amounts of $10 million to $50 million to four nonprofits that specialize in climate and energy research, the sources said. Those groups are the Energy Foundation, the Union of Concerned Scientists, the ClimateWorks Foundation, and the Rocky Mountain Institute.

These are large gifts, and they are going to large organizations. Each of the five groups receiving $100 million already has annual expenses in the nine figures. The largest of them, the Nature Conservancy, had a budget exceeding $930 million in 2018. Each has significant assets, offices and operations around the world, and enough heft to send experts to United Nations conferences.

Yet these gifts, even if spread over five years, will constitute a major portion of the groups’ revenues. And they put into perspective the mammoth size of the Earth Fund: These nine grants represent, at most, $700 million—that is, 7 percent of Bezos’s initial commitment.

But this first round of funding isn’t complete, a spokesperson for the Earth Fund told me. “This list does not reflect the complete range of organizations that the Earth Fund has been speaking with and that will be receiving grants from the fund in this initial round—stay tuned,” said the spokesperson, who did not confirm the grantees and amounts.

None of the would-be grantees offered a comment for this story. They declined to speak with me or did not respond to a request for comment.

These first grantees represent an older and—some would say—outdated approach to the problem of climate change. The youngest of the nine, ClimateWorks, was established in 2008; the rest were founded nearly three decades ago or more. Their approaches vary, and include that of the famously corporate-friendly Environmental Defense Fund and that of the scrappier Natural Resources Defense Council. The list may also raise eyebrows among those who have been following the recent scandals at the World Wildlife Fund and the Nature Conservancy.

But the groups are nearly all united in their history of work on environmental issues, and their treatment of climate change as such. With a few exceptions, they evince a pollution-centric view of the climate problem, calling for technocratic solutions that will slowly ramp down emissions. The Sunrise Movement, which boisterously supports a Green New Deal and electioneers for Democrats, is not among the groups I’m told will receive funding. Nor is any racial or environmental-justice group, nor any other organization that prioritizes climatic reconciliation as of a piece with racial equity.

And all of the recipient groups are 501(c)3 nonprofits, which means they are legally prohibited from intervening in political campaigns, or even appearing partisan.

Thinking of climate change in purely environmental terms is no longer a viable strategy. Carbon-based fuels are woven too deeply into the economy to simply be treated as a pollution problem. Climate change, as I’ve written in the past, is an economic problem—and its solution must be managed through economic policy. That is why the post-pandemic stimulus proposals of the United Kingdom, the European Union, and former Vice President Joe Biden all emphasize a green recovery.

Managing that economic transition will take new institutions and a new kind of economic expertise. Maybe that cause can receive some of Bezos’s remaining $9.3 billion.

Someone Else’s Weather

Brett Engel took these two photos from a spot overlooking Granby, Colorado: The first, which shows the East Troublesome Fire, was taken last week; the second was taken yesterday. (Thanks to his cousin, Weekly Planet reader Andi Rugg, for passing these along.)

Every week, I’m hoping to feature a weather photo from a reader or professional in this part of the newsletter, because the climate is someone else’s weather. If you would like to submit one, please email weeklyplanet@theatlantic.com.

3 Electoral Things

There’s more than one election happening today with high stakes for the fight against climate change.

I don’t mean the presidential race or the fight to control the Senate. (Though the Senate is arguably even more important for the climate’s fate than the White House is.)

I mean a set of smaller races that could shape the country’s path to fighting climate change for the next decade—regardless of who nets at least 270 Electoral College votes. These three state-level races, in particular, have big climate potential:

1. Texas Railroad Commission

What is it? Though it has a name worthy of Sir Topham Hatt, the Texas Railroad Commission, or RRC, has nothing to do with trains. It oversees the oil, gas, and energy industries in the Lone Star State, a role that makes it one of the world’s most important climate regulators.

Who’s running? Since 1994, the RRC has been under unified Republican control. But this year, Chrysta Castañeda, a Democrat and energy-industry veteran, is competitively running for one of the three commissioner slots. Her opponent, Jim Wright, won the Republican primary in an upset and once had to pay the commission a six-figure fine for environmental violations.

What’s at stake? Texas oil drillers “vent” or “flare” so much natural gas into the atmosphere that in 2018 they burned off more than the state of Arizona consumed. The practice is awful for local air quality and catastrophic for the climate—methane, the by-product of burning natural gas, is up to 86 times more potent at trapping heat than carbon dioxide. Castañeda has vowed to limit the pollution.

2. Arizona Corporate Commission

What is it? A five-member state agency that regulates electric utilities, gas companies, pipelines, railroads, and—in a weird twist—how businesses are incorporated in Arizona. It is essentially “a fourth branch of government,” David Pomerantz, the executive director of the Energy and Policy Institute, told me.

Who’s running? Republicans have long controlled the ACC; this year three Democrats are running for the three open seats as the “Solar Team 2020.” If Democrats win two of those seats, they will control the commission.

What’s at stake? In 2014, the state’s monopoly power company, Arizona Public Service Electric, secretly donated more than $10 million to groups supporting anti-solar commissioner candidates. Those candidates won, hiked utility rates on customers, and passed anti-solar policies.

With just two more Democratic votes, the commission could instead make sunny Arizona a solar powerhouse.

3. The Minnesota statehouse

What is it? The constitutional, bicameral legislature of the great state of Minnesota.

Who’s running? Democrats and Republicans.

What’s at stake? Minnesota has the country’s only divided state legislature: Democrats control the lower chamber, while Republicans control the upper. Last year, the two parties made little progress on passing a state climate policy. With unified Democratic control, Governor Tim Walz, whose first term ends in 2022, might pass policies such as a 100 percent clean-electricity mandate.

When can we expect the results? In all of these races, results should come in tonight, tomorrow at the latest, but in Arizona final absentee ballots won’t be counted until the end of the week.

Any interesting congressional races? I’ll be looking to see whether Representative Brian Fitzpatrick, a Republican of Pennsylvania, retains his seat even as his suburban district likely goes for Joe Biden. If so, he will be the last Republican in Congress who supports a carbon tax.

And in the South, watch to see whether Joe Cunningham, a Democrat of South Carolina, wins reelection. He triumphed in 2018 in a largely coastal district where sea-level rise is a major issue. Yet his Republican challenger this year has questioned the existence of climate change.

Thanks for reading. Did someone forward you this newsletter? Sign up here.