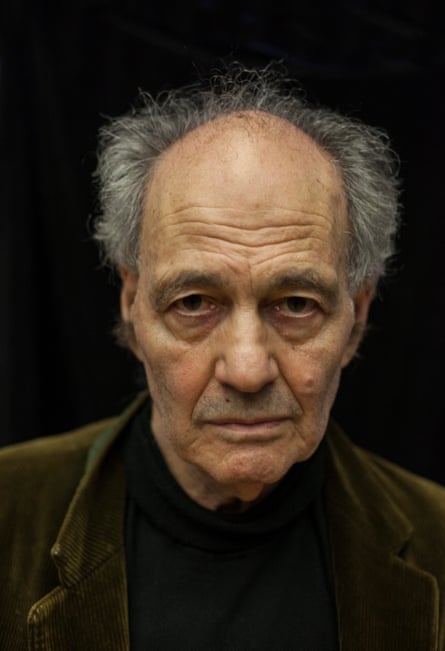

What do you do when you are a portrait painter but can’t get anyone to sit for you? Frank Auerbach, once described by the Tate as “one of the greatest painters alive today”, has come up with an answer he didn’t expect to find. At 91, he has painted himself – and it’s all thanks to Covid.

For decades, the painter and draughtsman has had friends and family sit for his portraits every week – until the lockdowns left him without any sitters. Instead, he found inspiration in his own features for a major series of self-portraits. He told the Observer that, while he had previously been uninterested in his own face, ageing has made it much more compelling.

“I did draw one or two self-portraits before but I’ve always felt there was something a bit banal about doing self-portraits,” he said. “I didn’t find actual formal components of my head all that interesting when I was younger, smoother and less frazzled.

“Now that I’ve got bags under my eyes, things are sagging and so on, there’s more material to work with. To my surprise, because I was on my own and had drawn the first one of this series, I’ve been continuously interested.”

William Feaver, former art critic of the Observer and one of Auerbach’s regular sitters, described them as “the most remarkable sequence of self-portrait drawings”.

“They are completely unplanned and unpremeditated,” he said. “A kind of journal of the plague years, which we all lived through. It’s a great sequence of drawings by somebody undergoing the state of being holed up, frustrated.” Feaver has selected 20 of the new works for his forthcoming book, titled Frank Auerbach, an updated and expanded edition of his acclaimed 2009 volume.

Auerbach is regarded as one of today’s most inventive and influential artists, revered for psychologically probing portraits and powerful urban landscapes that capture the soul of a person or place with thick lines and thickly layered brushstrokes. In 1986, he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, and in 2015 was the subject of a major retrospective at the Tate, which noted that Auerbach is often compared to Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud “in terms of the revolutionary and powerful nature of his work”.

Feaver has sat for Auerbach every week since 2003, for two hours at a time. He said: “It takes months to produce a painting or a drawing. In his view, painting and drawing are exactly the same difficulty and take roughly as long as each other. We tend to talk for the first hour of the two-hour session and be more or less silent the other.”

In the book, Feaver writes of the lockdown’s impact on Auerbach’s creativity: “There were to be no more sittings for upwards of 18 months. And so, mostly confined for the duration to his rooms in Finsbury Park [London], Auerbach looked to draw himself (‘give oneself a bit of hope’), the images testimony to his situation. Two dozen or more of them were realised over the months, chin up, eyes narrowed, each mirror reflection setting him apart. Portraits derived from sidelong stares and snap reactions, during which hand and eye and recall had to correlate – quick as a blink – the shifts between observation and execution.”

The self-portraits are mainly acrylic on board and graphite on paper, and measure up to 2ft 6in by almost 2ft (77.5 x 57cm). Feaver said: “He’s produced some of the great paintings of the 20th century, now the 21st century. Self-portraits have the implication of self-regard and there’s absolutely nothing of that in these. They show all sorts of frustrations and irritations and breath held – all the things we feel if we look in the mirror There’s a look. One narrows one’s eyes if one’s trying to outstare oneself in the mirror. If one’s then got to switch to the sheet of paper alongside, it’s a mental skipping all the time.”

Auerbach said that he is continuing to create further self-portraits: “I’ve been going on all day for the last two years, seven days a week. Each one is a totally different problem in terms of materials [and] what I’m thinking of.”

Asked whether he has learned something new about his face, he said he has never thought in verbal, emotional or psychological terms about his subjects as that “undermines what one is doing. I’m simply trying to use the subject to make an image of my impression of it.”