State policymakers have many opportunities to continue building the state’s fiscal health and invest in the people of California as they consider policy priorities for 2020-21 and beyond. While California is a wealthy state home to many high-income households and businesses that have been able to greatly leverage resources and expand their wealth in the last several decades, millions more Californians live a different reality every day. Workers in low- and mid-wage jobs are unable to afford the high cost of living – from paying for housing and child care to stretching their paychecks at the end of the month to cover food and medical bills. This is true no matter what region Californians work in across the state and call home. For women, Californians of color, and immigrants the economic challenges and disparities are vast. The state is in danger of allowing millions of Californians to spend their lifetimes in financial distress.

California can do better for its people. The state’s policy choices can help more people earn adequate incomes, build wealth, and afford basic necessities that will allow them to live, learn, work, and age comfortably in their homes and communities. With renewed discussions about the state’s available resources, healthy reserves, and the need to plan for the future, this analysis provides five facts that show why state leaders should ensure that all Californians share in the state’s vast wealth.

1. Economic Inequality Has Worsened for Californians, Reinforcing Racial and Ethnic Disparities

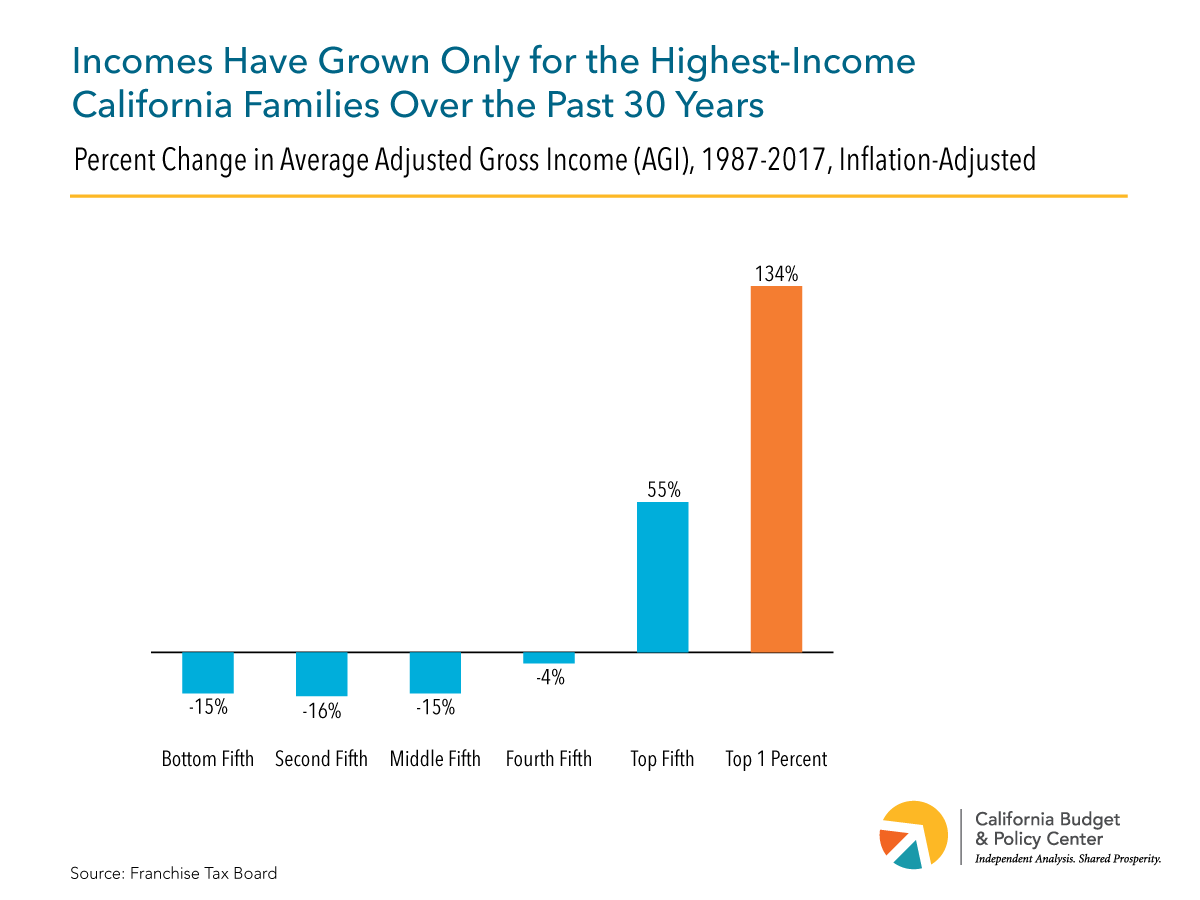

In the last three decades, economic inequality in California has significantly increased as incomes have grown only for the highest-income families. This increase in inequality is especially dramatic when accounting for not just earnings from work, but also unearned investment income, such as capital gains, which mostly goes to families with the highest incomes.1 Specifically, the average adjusted gross income – income reported for tax purposes, including investment income – for the top 1% has more than doubled, increasing by 134% between 1987 and 2017, while average incomes for the bottom 80% of Californians have decreased, after accounting for inflation.

The yearly income for the average California household in the top 1% in 2017 was $2 million, while the average household in the middle quintile received just $41,000. This means that, on average, the top 1% brought home in one week what Californians in the middle quintile received in one year. Viewed another way, in 2017 alone, the top 1% of California households – totaling 168,000 households – collectively received over $340 billion.2 This is more than double California’s General Fund spending in the 2019-20 budget and more than 10 times the income needed to lift every Californian above the poverty line.3 This concentration of income at the top reinforces racial and ethnic disparities and prevents economic gains from being shared equitably as Black and Latinx Californians are underrepresented among the highest-income households due to legacies of racist policies and ongoing discrimination.4

2. Child Poverty Remains High, Especially for Black and Latinx Children

Child poverty is one of the most significant challenges facing Californians. Nearly 1 in 5 children in the state (19.8%) – 1.8 million in total – lived in a family that could not afford basic needs in 2018.5 The vast majority of these children live in working families, which means that their families’ economic challenges largely result from low pay, especially relative to high housing costs. Children of color, particularly Latinx and Black children, are far more likely to experience economic hardship in California. Nearly one-third of Latinx children (31%) and over one-quarter of Black children (26%) lived in poverty between 2013 and 2017 – more than twice the share of white children in poverty (12%). This substantial gap reflects a number of factors. For example, Latinx and Black Californians are more likely to be paid low wages and to experience financial strain due to high housing costs than white Californians. In addition, Latinx, Black and other Californians of color are less likely to own their homes and have other forms of wealth that help families weather financial setbacks.6

3. Workers’ Wages Remain Stagnant as Housing Costs Significantly Increase

Rising housing costs and stagnating wages are two key challenges Californians face each day as too many struggle to make ends meet. The high cost of housing in many parts of California is one of the primary drivers of California’s high poverty rate – ranked first among the 50 states – under the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which accounts for differences in the local cost of living. Unaffordable housing costs contribute to the homelessness crisis California faces, with over 150,000 homeless residents in 2019, the vast majority of them unsheltered .7 Housing affordability is a challenge Californians experience in all regions of the state, even in areas with lower housing costs, because incomes are also typically lower in these areas. Renters and households with the lowest incomes are hit the hardest. Specifically, more than half of California renter households and 8 in 10 households with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty line pay an unaffordable share of income toward housing.

Why is housing affordability particularly challenging for Californians with lower incomes? A key reason is that earnings for low- and mid-wage workers have not kept pace with rising housing costs. In the last decade alone, median household rent has increased by 16%, far outpacing the growth in annual earnings for the typical full-time worker, which grew by only about 2% during the same period, after accounting for inflation. In fact, wages for workers at the low end and middle of the wage scale have been largely stagnant across the past few decades, growing by just 1% and 4%, respectively, after adjusting for inflation. Californians of color are especially affected by these problematic wage trends, because they are disproportionately represented at the low end of the wage scale, typically earning less per hour than white workers. These simultaneous trends of rising housing costs and stagnant earnings for workers with low and middle incomes have triggered a crisis that calls for bold and immediate interventions.

4. Economic Insecurity Has Serious Consequences – But Policy Choices Can Make a Difference

What are the consequences when families and individuals find themselves unable to make ends meet? Californians struggling with economic insecurity face difficult decisions about which basic needs to cover and which to forego. For a single-parent family with two children in California, the average cost of a modest basic needs budget – including housing and utilities, child care, food, health care, transportation, taxes, and miscellaneous other necessary expenses – totals more than $65,000, with housing and child care making up more than half of the total budget. When families do not have enough resources to cover their basic costs, they may be forced to go without adequate food, leave health problems untreated, rely on unstable or unsafe child care, or even fall into homelessness. These experiences can have serious consequences for individuals’ health and for children’s long-term educational and economic outcomes. However, policy choices coupled with state investments can help more Californians achieve economic security, and many different policy approaches are available. Policies that increase incomes or make basic needs more affordable allow families and individuals to stretch their resources further and address their most pressing needs.

5. California Can Increase Revenue, Support Investments, and Share the State’s Prosperity

Supporting policy decisions and ongoing investments to ensure that all Californians share in the state’s prosperity requires a fair and stable revenue system. This is also necessary to protect Californians against hardships during economic downturns. California has the space to generate additional revenue, and policymakers can start by re-evaluating the state’s current system of “tax expenditures.”8 These are tax breaks for individuals and businesses that reduce revenues available to invest in the millions of Californians who face challenges, such as persistent poverty and housing cost increases that have far outpaced wage growth. California will lose an estimated $63 billion – more than 43% of the General Fund budget – to individual and business tax expenditures in the 2019-20 fiscal year. Many of the state’s most expensive tax expenditures primarily benefit higher-income households, exacerbating income and wealth inequality, while others – targeted to businesses – serve dubious purposes or are of questionable effectiveness. One consequence of business tax expenditures, combined with corporate tax rate cuts over past decades, is that the share of corporate income paid in state taxes has declined by more than half since the 1980s. Policymakers could make the tax system fairer and raise additional revenue to support investments that not only help Californians cover the costs of their basics needs but also help low- and middle-income households build their wealth. Achieving these priorities requires not just examining tax rates and exploring potential new sources of revenue, but also engaging in a comprehensive review of the state’s tax expenditures – and eliminating or restructuring those that are ineffective or inequitable.

Conclusion

Policymakers can make a commitment to all Californians: as the state looks to secure and build its wealth it can also seek policies that support children, families, and individuals struggling to afford the costs of living who are blocked from sharing in the state’s prosperity. By pursuing policies that prevent the concentration of wealth and income from being held amongst a few, state lawmakers can also address the structural racism that blocks Californians of color from expanding their incomes and wealth. California has the resources to do better for all its people.