Lost in the uproar over the NFL sideline protests against police brutality are newly released statistics showing that the threat to black men is skyrocketing — not from trigger-happy or racist cops, but from crime.

More than any other demographic group, black men are paying the price with their lives with a surging violent crime rate over the past two years, including a 20 percent jump in the overall homicide rate, even as the number of blacks killed by police declines.

Using homicide figures from the 2016 FBI Uniform Crime Report released Sept. 25, Manhattan Institute fellow Heather Mac Donald found that the number of black homicide victims has jumped by nearly 900 per year since the Black Lives Matter movement took root in 2014.

“The majority of victims of that homicide surge have been black,” Ms. Mac Donald said in an email. “They were killed overwhelmingly by black criminals, not by the police and not by whites.”

Meanwhile, the number of blacks killed by police dipped from 259 in 2015 to 233 in 2016, with 2017 so far coming in below both years with 175 deaths as of Oct. 12, according to The Washington Post’s Fatal Force database.

Crime statistics are notoriously slippery: The FBI Uniform Crime Report depends on local departments to report their statistics voluntarily, and the figures tracked by sites such as the Killed by Police page on Facebook differ from those of The Post.

In addition, the percentage of blacks killed by police has long been more than double blacks’ percentage of the population — about 13.3 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Likewise was the percentage of blacks involved in violent crime.

Still, the dramatic increase in black homicide victims has raised questions over whether NFL players taking a knee in a statement against racially motivated police violence are missing the larger problem.

“If these wealthy football players really cared about saving black lives, they would support proactive policing and denounce criminality,” said Ms. Mac Donald, author of “The War on Cops” (Encounter Books, 2017). “When the police back off of proactive policing in high-crime areas, black lives are lost.”

The FBI reported that violent crime jumped in 2016 by 3.4 percent nationwide, the largest single-year increase in 25 years, which “reaffirms that the worrying violent crime increase that began in 2015 after many years of decline was not an isolated incident.”

In addition, the number of homicides rose by 7.9 percent “for a total increase of more than 20 percent in the nationwide homicide rate since 2014.”

Ms. Mac Donald and others have blamed the increasingly hands-off approach of police officers who are worried about running afoul of the Black Lives Matter movement after the 2014 shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. She dubbed it “the Ferguson effect.”

Peter Moskos, associate professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, tracked the same phenomenon in Baltimore after the April 2015 rioting over the death of a black man in police custody. He calls it “the Freddie Gray effect.”

He found a spike in homicides and shootings after the riots, which were followed by Baltimore State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby’s decision to charge six officers in Gray’s death. Three of the officers were acquitted in non-jury trials, and charges against the other three were dismissed.

“Police were instructed — both by city leaders and then in the odd DOJ report city leaders asked for — to be less proactive since such policing will disproportionately affect minorities,” Mr. Moskos said in a Sept. 4 post. “Few seem to care that minorities are disproportionately affected by the rise in murder.”

Yet such statistics can’t compete for headlines with high-profile officer shootings such as the February 2016 barrage of bullets that killed a black couple — Kisha Michael and Marquintan Sandlin — reportedly unconscious at the time in their car in Inglewood, California.

Black Lives Matter has called for the five officers involved to be charged, while protests are continuing in St. Louis after a white police officer was acquitted of murder last month in the 2011 death of Anthony Lamar Smith.

Why the lack of focus on black-on-black crime? Those involved with Black Lives Matter have said in the past that prosecuting such killings is easier than cases involving police force against civilians.

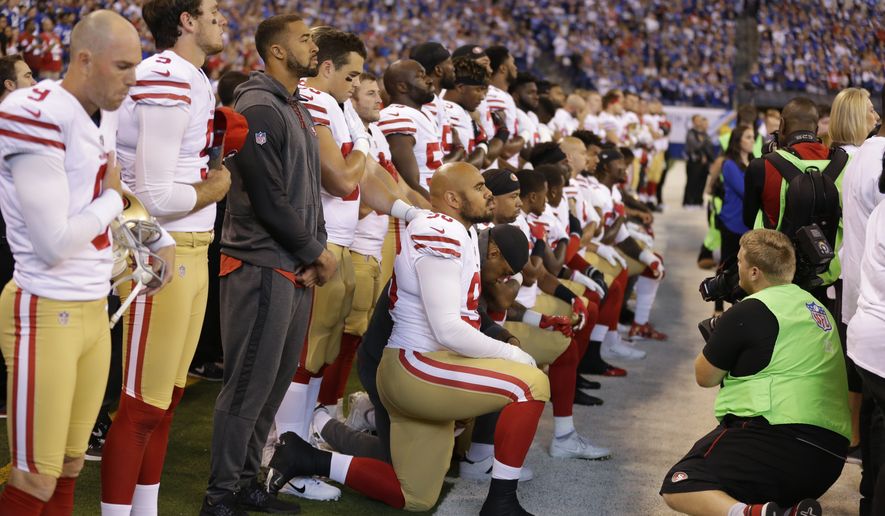

While the NFL kneeling began as a protest against police brutality, those involved have increasingly expanded the point to encompass what San Francisco 49ers safety Eric Reid described as “systemic oppression that has been rampant in this country for decades and decades.”

Rashad Robinson, senior campaign director at Color of Change, said President Trump’s recent suggestion that owners should fire players who refuse to stand for the national anthem represents a view within sports that “black people serve at the pleasure of white people.”

“Almost every NFL owner is white. Nearly 70% of players are Black,” Mr. Robinson said in a written statement. “Yet for Donald Trump this power imbalance is not enough — he wants to be sure that players who exercise their right to protest social injustice can be fired with impunity. This is what it means to advance a white supremacist worldview.”

The latest crime figures support what rank-and-file officers are witnessing in terms of street violence, said Bill Johnson, executive director of the National Association of Police Organizations, which represents 241,000 cops.

“It jibes with what our members are telling us,” said Mr. Johnson. “Violence in general is up in the sense that whether it leads to reported crime or arrests. Just the situation in our communities and our streets is worse than it was three years ago, certainly before the agitation from Black Lives Matter.”

Officers also have been hit: Ms. Mac Donald said there was a 53 percent increase in 2016 in the shooting deaths of cops, while The Washington Post database found that only 16 of the 233 black men killed by police in 2016 were unarmed.

“A police officer is 18 times more likely to be killed by a black male than an unarmed black male is to be killed by a police officer,” Ms. Mac Donald said. “Black males have made up 42 percent of all cop killers over the past decade, though they are only 6 percent of the population.”

The worst part is that those suffering from the higher crime rate are those who can least afford it, Mr. Johnson said.

“It’s the communities themselves — people who are being victimized, people who are being murdered, families who are losing loved ones, kids who are afraid to go to schools, business people who won’t open up a business because the neighborhood is too rough — that’s who’s suffering,” he said.

Not all neighborhoods are hit equally.

“It tends to be poor communities, communities of color,” Mr. Johnson said. “Communities that are already suffering from higher crime rates than their neighbors who need safe, effective, thorough law enforcement.”

• Valerie Richardson can be reached at vrichardson@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.