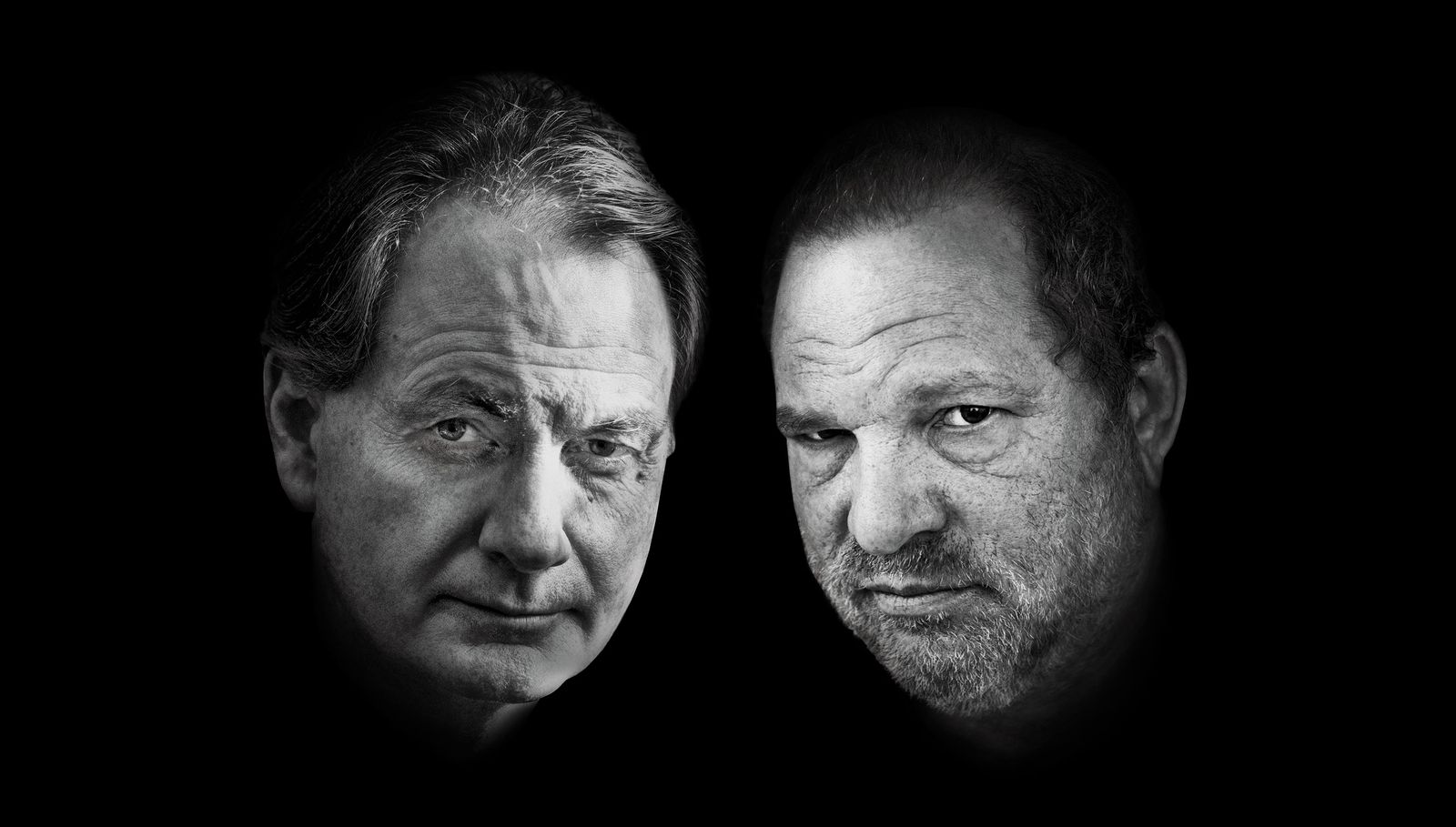

Early in the evening of March 27, 2015, a young Italian model named Ambra Battilana walked into the NYPD’s 9th Precinct house, a few blocks from Tompkins Square Park. She was so physically and emotionally distressed that the desk sergeant almost called an ambulance. When two patrol officers transported her to the 1st Precinct house, in Tribeca, she cried throughout the short drive. There, at 8:20 p.m., she made a formal complaint that she had been sexually assaulted by Harvey Weinstein.

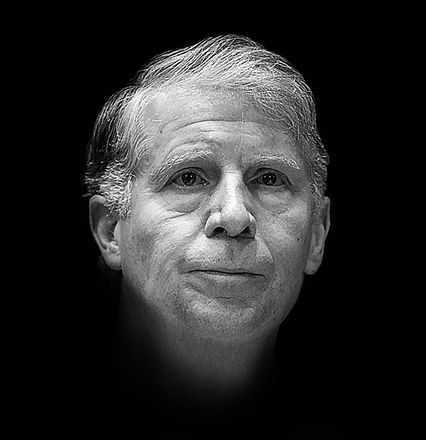

By nine o’clock, the commander of the NYPD’s Special Victims Division, Michael Osgood, had been notified. Osgood understood immediately that the case had to be handled with extreme care. He and Lieutenant Austin Morange, head of the SVD’s Manhattan unit, mapped out a plan to keep the case under wraps, to prevent Weinstein from calling in his army of high-powered lawyers and publicists. Knowledge of the investigation, they decided, would be confined to a small circle of detectives and supervisors. Their reports, contrary to standard procedure, wouldn’t be loaded on the NYPD’s system, and Osgood orally informed his boss, Chief of Detectives Robert Boyce, rather than putting his briefing in writing.

Then Morange called Martha Bashford, head of the Sex Crimes Unit at the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, to apprise her of the complaint. The call was made reluctantly, after much internal debate. Osgood’s team felt that ever since 2011, when District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. had been blasted in the press for dropping a sexual-assault case against IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the DA’s office had been gun-shy about taking on powerful defendants. While Osgood cannot talk about the case his team built against Weinstein, sources close to the investigation provided the first detailed account of its inner workings — and how the police became convinced that Vance’s office was systematically working to derail the investigation.

In the station house that evening, Battilana told an SVD detective that Weinstein had invited her to a meeting earlier that day, saying he might have work for her. As soon as they were alone in his office, he reached out, two-handed, and groped her breasts. She told him to stop, but he put a hand on her left thigh, moved it up under her skirt, and asked for a kiss. When she refused, he told her he was a very powerful man, boasting that he could make her $2 million a year. The meeting ended with Weinstein telling his receptionist to get Battilana a ticket to that night’s performance of Finding Neverland on Broadway.

Just then, as Battilana was providing her account to the SVD detective, she got an email from Weinstein. Why hadn’t she shown up at the theater, he wanted to know. Recognizing an opportunity for a “controlled call” — a police technique used to solicit and record incriminating evidence — the detective instructed Battilana to reply to the email and say that she didn’t have his phone number. They exchanged numbers, and Weinstein called.

“How did my breasts feel?” Battilana asked him, as the detective had coached her. (A flat-out accusation isn’t a good strategy for a controlled call. “Why did you touch my breasts?” is only likely to prompt an apology, which isn’t an admission.)

“They felt beautiful,” Weinstein replied, according to a source who heard the recording. “They’re great.”

The call was used to set up a meet with Weinstein — one that would be surveilled and recorded by the SVD — for the next day, at the Tribeca Grand Hotel. At one o’clock that Saturday afternoon, Lieutenant Morange called Bashford at the DA’s office to tell her about the meet. “Her response to it was, in sum and substance, that it was fine,” recalls Michael Bock, a retired sergeant who was one of only six SVD members privy to the investigation. “At no time did she request to prep the victim or direct any specific questions to be asked by the victim during the controlled meet. In other words, she didn’t participate, but the opportunity was there.”

At the Tribeca Grand, detectives listened in as Weinstein again admitted to fondling Battilana’s breasts, all the while trying to wheedle and bully her into a room he had rented in the hotel. Once Battilana had gotten safely away, Morange and another officer approached Weinstein, asking him to come down to the station house. Weinstein refused. “He threatened to call the police commissioner,” Bock says. When Morange told him that the commissioner knew they were there — a bluff the egotistical Weinstein readily believed — he agreed to go with them.

On the way to the precinct, Weinstein threatened Morange and the two detectives escorting him, telling them he was going to call Police Commissioner William Bratton, former commissioners Ray Kelly and Bernard Kerik, and former mayor Rudy Giuliani. By messing with him, Weinstein said, they were putting their jobs in jeopardy.

At the precinct, Weinstein demanded to know why he had been hauled into the station. As soon as Battilana’s name was mentioned, he invoked his right to counsel. “All he needed to know was her name,” Bock says. Weinstein’s machine went into high gear. He retained two lawyers with ties to the district attorney’s office, including Elkan Abramowitz, Vance’s former law partner and a donor to his campaign. To cement their access to Vance’s office, the lawyers hired Linda Fairstein, the former head of the DA’s Sex Crimes Unit and a close friend of Bashford’s.

On April 1, five days after Battilana had filed her complaint, Bashford conducted an interview with her. The next day, sources say, Vance’s office sent its own investigators to Battilana’s apartment. There, according to Bock, they aggressively questioned her roommates. Was Battilana a prostitute? Did she bring home lots of strange men? Was she a stripper? The DA’s office also reviewed video from the apartment building’s surveillance cameras, which would enable them to create a record of Battilana’s personal life. “When she found out about this, the victim became afraid,” recalls Bock. “She began to cry.”

According to Bock, Osgood believed that Vance and his office were actively working to discredit Battilana. So the chief and his team decided to take an extraordinary step. “We decided we’re going to hide the victim,” Bock says. “From the DA.”

On April 2, under the direction of Osgood, the SVD put Battilana in a hotel, registering her under a false name. For the next five nights, she was kept safe from Vance’s investigators, first at the Franklin Hotel, then at the Bentley. A 22-year-old woman had come forward to accuse one of the most powerful men in Hollywood of sexual abuse, and the police decided she needed protection — not only from her alleged assailant, but from the elected official responsible for prosecuting him.

The Special Victims Division is headquartered in a gray brick building on Avenue C, where the front doors are routinely stuck halfway open and, at night, roof floodlights give the humble edifice a penitentiary glare. Outside of Chief Osgood’s office there are dozens of desks, set side by side, where SVD detectives comb over every sex-crimes complaint made in the past 24 hours to make sure they were classified correctly. That was one of the first and most sweeping changes that Osgood made when he took over Special Victims in 2010. Too many rape complaints, he discovered, were improperly dismissed as “unfounded,” while attempted rape was often misclassified as forcible touching, a misdemeanor charge. Shortly before Osgood took command, a journalist named Debbie Nathan had been grabbed by a man and dragged into the woods in Inwood Hill Park, where he rubbed himself against her. “Special Victims showed up and made it a forcible touching,” Osgood recalls. “Yeah, she was grabbed — but that’s not what his intended goal was. He wasn’t gonna bring her into the woods and practice salsa dancing.” Osgood implemented what he called the “attempted-rape rule,” ordering investigators to take into account a perpetrator’s intent. “The worst thing you can do to a victim is to improperly classify her complaint,” he says. “Plus, I need to know if I have a possible rapist, so I can zero in on him.”

When then-commissioner Ray Kelly tapped Osgood to oversee the SVD, the unit was in bad shape. For many years, the NYPD had treated Special Victims like an investigatory backwater. “If you couldn’t cut it someplace,” Chief Boyce recalls, “we’d send you there.” Although the division was slowly beginning to improve, Osgood found that detectives were still making too many “jump collars” — premature arrests on slim evidence, which led to innocent people being picked up and guilty ones being let go. SVD detectives fought incessantly with prosecutors, each unit in the division acted as a world unto itself, and there was deep distrust between the SVD and advocacy groups for sexual-assault victims. When Monica Pombo, a social worker at the nonprofit Crime Victims Treatment Center, took a job at the NYPD, her fellow advocates responded warily. “Oh,” they said, “you’re going over to the other side.”

Osgood, who had spent eight years heading up the NYPD’s Hate Crimes Task Force, had developed a reputation for solving high-profile cases and working closely with traumatized victims and their communities. A former Marine who stands six-foot-four, he has the forthright manner of a seasoned cop, coupled with a buoyant, restlessly tuned energy; many of our conversations were accompanied by the sound of his fingers drumming on the tabletop. Around the NYPD, where excessive reading is viewed with a degree of suspicion, he’s often referred to as an academic. “He’s not a regular chief,” says Boyce. “He’s an expert in his field, and he has an unbelievable amount of knowledge.” Osgood majored in mathematics in college, and the shelves in his office are lined with books on criminal investigations, complex-systems theory, advanced management, biochemistry, and probability — a collection Osgood describes as a “body of knowledge and set of modern intellectual thought that is necessary to move policing forward.”

Osgood used such thinking to hone the way the NYPD investigates hate crimes. Breaking with long-established traditions of policing, he eliminated the military-style hierarchy ingrained in the NYPD, creating a flat command structure that allows for a constant flow of real-time information between detectives and supervisors. When a hate crime was especially violent or complex, he flooded the crime scene with manpower — a move his detectives affectionately call “an Osgood mobilization.” In what has become a mantra for Osgood, he imposed “investigative process discipline,” pushing his team to follow each investigative pathway to the very end, no matter how time-consuming or frustrating it might be. Searching for witnesses in one homicide case, for example, detectives in the hate-crimes unit identified and tracked down the six bus drivers who were working the B38 route in Bushwick the night of the murder. That step alone took two weeks, and led nowhere.

Employing such unconventional techniques paid off. The Hate Crimes Task Force, which Osgood continues to lead, has solved every case of stranger homicide it has investigated in the past 15 years. By contrast, the national solve rate for homicides — the majority of which involve known offenders — is roughly 65 percent.

Osgood brought the same instincts as a reformer to the task of investigating the more than 5,000 rapes and other sex crimes reported in New York City each year. When he took over the SVD, he knew nothing about what he calls the “hard, hazy world of sexual-assault complaints.” Years before Weinstein’s predatory behavior helped spark the #MeToo reckoning, Osgood decided that the cops needed to do a better job of listening — not only to the victims of sexual assault but also to the vocal and organized network of social workers, doctors, and prosecutors who advocate on their behalf. Going against the culture of the NYPD, Osgood allowed victims’ advocates to step inside the closed world of the Special Victims Division and independently audit case files — a step that only two other police departments in the country have taken. He sits down with advocates twice a year to hear their criticisms and suggestions, and he makes a point of being on call whenever they spot something that needs fixing.

“We have his phone number, and he’s always available,” says Brigitte Alexander, an emergency-medicine physician who formed the first sexual-assault response team for the city’s public hospitals in 2004. “So if there’s a problem, like some patrol officer not taking a report, it’s very easy to make that call and get it resolved. Honestly, before he took over, that did not exist. There’s a level of openness and professionalism that just wasn’t there 20 years ago.”

At the same time, Osgood ordered SVD detectives to stop jumping the gun on arrests. “I communicated to the whole division that we’re not a jump-collar division,” he says. “We’re a beyond-a-reasonable-doubt division.” He studied the science of DNA — “the molecular structure, DNA-extraction technology, the probability mathematics” — and created a DNA Cold Case squad that has resolved more than 1,800 dormant cases. Most recently, he formed a new squad dedicated to reexamining 4,000 unsolved cases of stranger rape.

The Stranger Rape Cold Case unit was formally approved by Commissioner James O’Neill in February, after Osgood and the SVD reopened and solved one of the NYPD’s most infamous cold cases. In 1994, a 27-year-old Yale graduate was raped in broad daylight by a stranger in Prospect Park while she was walking home from the grocery store. But as SVD detectives worked to solve the case, a high-ranking police source told the Daily News that the victim was lying, and the paper published a series of columns dismissing the attack as a “hoax.” The victim described the experience as being raped twice. Using new technology, Osgood’s team managed to match DNA evidence from the original investigation to a serial rapist who was serving a 75-year sentence in Sing Sing.

Osgood brought the victim to his office to give her the news personally. “I don’t know how to say this,” he told her, “but we solved your case.” She broke down in tears. Osgood also apologized to her, on behalf of the NYPD, for whoever had smeared her in the press.

The biggest innovation that Osgood brought to the Special Victims unit — one that is only now beginning to make its way across the country, police department by police department — was also the trickiest to implement. The NYPD’s police academy, Osgood observed, offered a range of courses on questioning suspects but none on talking to victims. As a result, SVD investigators were stuck in a “who, what, when, where, and why” mind-set. They wanted the facts, ideally in chronological order. “Start from the beginning,” they might tell a victim. “What time did this happen? Tell me the exact location where he first approached you. What color shirt was the suspect wearing?”

But victims of sexual assault are often unable to answer such straightforward questions. There will be gaps in their stories. Events will be out of sequence. And the fractured nature of their testimony can lead investigators to conclude that they are unreliable at best or dishonest at worst. “What I saw time and time again is something like this,” Osgood says. “A victim says, ‘I was walking down the street, a red van passes me, and then I’m assaulted.’ But when you pull video, you see that she’s walking down the street, she’s assaulted, and then a red van passes. Most police departments would go, ‘Oh, she’s inconsistent, she’s lying.’ ”

Osgood saw the phenomenon play out in one of his earliest cases at SVD. On Memorial Day in 2011, an 85-year-old woman was sexually assaulted while taking her early-morning walk on East 83rd Street, just four blocks from Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s townhouse. The media jumped on the story, and Osgood assembled an investigative team of more than 60 detectives. After the police released video images of the suspect dragging the woman into a stairwell, someone identified him as the same person who hung around his apartment building in East New York. But when SVD detectives staked out the location and grabbed the guy, they noticed something odd.

One of the detectives immediately called Osgood. “Chief, we don’t think this is the guy,” he said.

“Why?” Osgood asked.

“He’s got a New York Yankees tattoo on his face,” the detective explained. It was inked on his left cheekbone and it was pretty big — larger than a silver dollar. But the victim, when giving her physical description of the suspect, had never mentioned it.

“Bring him in,” Osgood told the detective. “He’s the guy.” And he was. DNA lifted from the elderly women’s blouse matched that of the 32-year-old suspect.

In 2015, a deputy commissioner named Susan Herman, who works closely with victims, handed Osgood a research paper about something called the Forensic Experiential Trauma Interview. Developed by Russell Strand, a former special agent with the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command, FETI drew on emerging neuroscience that dovetailed precisely with what Osgood has observed in action. “Memory encoding during a traumatic event is diminished and sometimes inaccurate,” Strand wrote. When trauma occurs, the prefrontal cortex often shuts down, and more primitive parts of the brain take over. Information necessary to survival continues to be recorded, Strand explained, but the primitive brain doesn’t do very well “recording the information many professionals have been trained to obtain.”

Osgood, who was making notes in the margin, only had to read the first page to feel the kick of recognition. “This guy’s correct,” he said to himself. “This is what I’ve been seeing over 14 years.”

Osgood decided to fly to Idaho, where a former detective named Carrie Hull, one of the country’s leading innovators in sexual-assault investigations, was offering a training program in FETI. He brought along Monica Pombo, the victims’ advocate who had joined the NYPD, and Bock, one of his most “experienced, gritty sergeants.” If his seasoned vets couldn’t learn FETI, Osgood reasoned, or if they balked at the process, it wouldn’t matter how effective the technique was.

“I was skeptical,” Bock admits. “It’s not the normal way of doing business. But going out there, I kept an open mind. Maybe they know something that we didn’t.”

Osgood, Bock, and Pombo were blown away by what they discovered. FETI, it turned out, provides a way to interview victims that allows them to access the kind of rich and detailed information that investigators can then follow up on in the field. The questions are open-ended and empathetic — more an invitation to share than a relentless hammer to provide a precise chronological account. “What are you able to tell me about your experience?” takes the pressure off the victim to figure out what the investigator wants and allows for actual recollection. “What are you able to recall about what you heard or smelled?” taps into the victim’s deeper sensory experience. “What can’t you forget about your experience?” bypasses what the victim has forgotten and offers an entryway into other memories.

That night, over dinner with Hull and his colleagues, Osgood plunged right in. “I love this — I want this,” he said. “This is what I’ve been looking for.” Plates were pushed aside and everyone pulled out notebooks and pens, sketching out a plan to bring FETI to the NYPD. “When Chief Osgood gets excited, he just starts talking more and more and more and more and faster and faster and faster,” says Pombo. “He starts doing what he does well, which is saying: ‘This is great — here’s how it can be better.’ ” With the backing of Chief Boyce, Osgood put 30 of his best investigators through the FETI course, enabling him and Hull’s team to fine-tune it to match the needs of the NYPD. Today, all 144 detectives in the SVD who investigate sex crimes involving adults have received seven days of training in the technique.

“Of anybody we’ve worked with, the NYPD has made by far the most significant commitment in training their people,” says Hull, who has worked with police departments across the country. “Chief Osgood not only said, ‘Hey, what kind of training can I bring in?’ He went out and put himself through the trainings. You tend to see people that want a quick fix, but for him, it wasn’t just a way to check a box. He made sure it was the right fit for his department.”

Since Osgood took charge, Special Victims has solved 79 percent of all cases involving rapists who commit more than one assault — compared to a national average of 36 percent. But whatever innovations he has brought to the investigations of hate crimes and sexual offenses, there is one variable that remains outside Osgood’s control: politics. Five days after he and his team sequestered Ambra Battilana in a hotel room to protect her from Vance’s office, she agreed to meet with Martha Bashford, the head of the DA’s sex-crimes unit. Bashford didn’t inform the SVD, but Battilana’s lawyer did, and Osgood’s investigative team showed up at the attorney’s office before Bashford arrived.

During the meeting, according to Bock, Bashford grilled Battilana about her personal life — including one of the infamous sex parties thrown by Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi that she had attended.Battilana told Bashford that she and her friends had left as soon as the sex started. “The questioning was aggressive and accusatory,” Bock recalls. “Again, the victim was upset. She felt like she was under attack.”

Three days later, Bashford called Osgood’s team to inform them that Vance had decided not to prosecute the case. Weinstein’s team, which smeared Battilana in the press as a gold digger, reached a settlement requiring her to turn over a copy she possessed of the phone call recorded by the SVD. Anonymous sources close to Vance’s office, meanwhile, painted Battilana as an unreliable witness and blamed Osgood’s team for having moved too quickly. The SVD, a source told the New York Times last fall, failed to give prosecutors “an opportunity to help steer the secretly recorded encounter with Mr. Weinstein.”

Three years later, Bock is still incensed. “This is only a misdemeanor case!” he fumes. “It’s not a felony! They prosecute people for misdemeanors with far less probable cause than this. We gave them beyond a reasonable doubt. We obviously know who this man is. We obviously know we have a different burden of proof. So to go above and beyond as we did, he should’ve been arrested. He should’ve been arrested.”

The DA’s office continues to insist that it handled the case by the book. Joan Vollero, a senior adviser to Vance, denies that Osgood’s team notified Bashford about the complaint against Weinstein or consulted with her about the meet at the Tribeca Grand. Vollero also maintains that the DA’s office never interviewed Battliana’s roommates or questioned her aggressively. “It is customary for prosecutors to discuss potential areas of cross-examination when meeting with complainants,” Vollero says. “This characterization of the meeting is incorrect and, moreover, troubling. It was a normal, typical interview of a complainant.”

The deep-seated mistrust between the DA’s office and the SVD is bad news for the victims of sex crimes, who rely on public officials to bring their assailants to justice. In the wake of #MeToo, 14 women have filed sexual-assault complaints against Weinstein with the NYPD. This time around, to ensure that nothing goes wrong, Osgood has taken an extraordinary step: He personally conducted each of the investigations, along with two of his best investigators, Sergeant Keri Thompson and Detective Nicholas DiGaudio. The task force of three has worked on the case full-time since October, traveling to Paris, London, Toronto, Montreal, Florida, and California. Many of the cases had passed the statute of limitations, but five are now sitting with Vance, awaiting his decision on whether to issue an indictment. If Weinstein winds up in handcuffs, it will be in no small part because Osgood made sure the police covered every base.

One day not long ago, Osgood was sitting in his office, talking with several current and retired members of his team. Behind his desk hangs a print of the iconic painting Washington Crossing the Delaware. “I put that up there about 12, 14 years ago,” Osgood says. “And of course, the detectives said, ‘Oh, that’s Osgood leading the Hate Crimes Task Force.’ ”

Everyone laughs. “The first Osgood mobilization!” says Anthony Caban, a retired detective with the hate-crimes unit.

“That’s not what it is,” Osgood replies with a grin. “Emanuel Leutze was a German artist who came to America in the 1820s. He was amazed at the individual liberty he saw, so he paints this picture. I have it there because when you look in this boat — which is an incorrect boat, it’s not the type of boat they used — there are all these different identities …”

“Oh, you’re giving her so much of a yarn here, you don’t even know,” says James Byrne, an NYPD spokesman, to more laughter.

“And what Emanuel Leutze was trying to say …” Osgood plows on.

“Some of this stuff I think he makes up as he goes along,” injects Deputy Inspector Paul Saraceno, Osgood’s right-hand man.

“There are people of Scottish identity, Irish. There’s an African-American in there, there’s a person that looks somewhat female. The night when Washington crossed the Delaware, he was crossing it not for any one group — he was crossing for individual liberty, because all these different identities fought in the fight for independence. So I have it there to signify that in the United States, the right to identity safety is a core American principle. It’s an extension of individual liberty, and that’s what that represents.”

Osgood finishes. Drums his fingers on the tabletop. Gestures to the other cops in the room. “Even if these guys feel otherwise,” he says. More laughter.

Osgood knows he still has a lot of work to do at Special Victims. In 2015, the division’s reputation took a hit when the head of its Manhattan unit was forced to resign after his partner was accused of groping a rape victim during an investigative trip the two men took to Seattle. SVD remains seriously short-staffed, with each detective working as many as 130 cases a year. The interview rooms for victims are dingy and uncomfortable, and in most offices can be reached only by parading past a roomful of cops. And too many victims still don’t trust the police enough to come forward to report the abuse they’ve suffered. “This is probably the most important thing I can say, after doing 90,000 sexual-assault cases, 14,000 rapes, and 2,000 stranger rapes,” Osgood emphasizes. “Sexual assault is the hidden scourge on the American landscape. And it’s hidden because there’s such a vast underreporting of rape.”

He pauses, considering the high-profile investigation he has just completed and what it will take to confront the true scope of sexual assault. “Harvey Weinstein may be a watershed moment in the country,” he says. “We’re at a point in our history that it’s time for us to find a way to interdict this behavior. You can’t have tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of silent victims out there. I’ve learned the depth of the trespass and the damage this action causes. It’s time for us, as a people, to go out there and mobilize.”

*This article appears in the March 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!